The writers and editors of the Los Angeles Times Food section choose their favorites from the best cookbooks of 2022.

- Share via

Looking back at our favorite cookbooks of the year, their depth and scope is impressive. Among the authors are chefs, home cooks, photographers, bloggers and other storytellers. They shine a light on the best of what cookbooks can be. The top picks of the Los Angeles Times Food writers and editors speak to comfort cooking, baking, barbecuing, longevity, the immigrant experience, identity and activism — to show that food truly is a lens through which we can better understand the world, ourselves and each other.

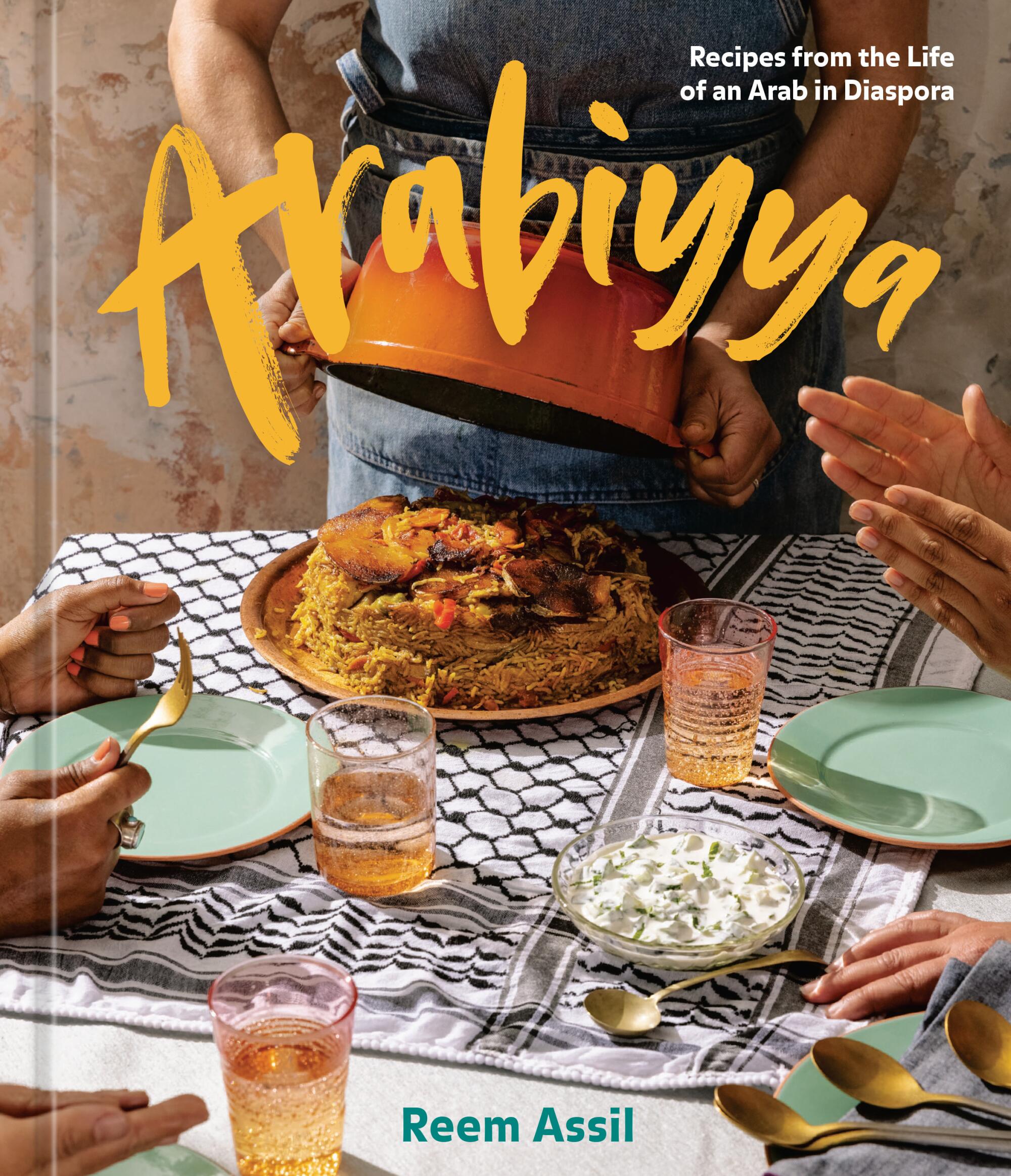

Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora

Reem Assil (Ten Speed Press).

If you know of Reem Assil — and of her restaurant Reem’s in San Francisco’s Mission District, inspired by the tradition of corner bakeries across the Arab world — you’re probably aware she brings more to the food space than first-rate baking skills. She was a labor and community organizer before becoming a full-time chef, and she brings an activist’s soul as well to her culinary career. Beyond converting Reem’s to a worker-owned model in an effort to capsize hierarchical restaurant models, Assil has the courage to be outspoken on many topics: among them Palestinian rights, the intersection of food and social justice, and the many ills of capitalism.

She pours the whole of her experience into her first cookbook. Detailed, lucid instructions for delving into the baking customs of Belad al Sham (the Greater Syria region) anchor “Arabiyya,” including Assil’s secrets to mana’eesh fragrant with za’atar and olive oil, ring-shaped ka’ak crusted with sesame seeds and tutorials on spinach-stuffed fatayer and other savory turnovers. Subsequent chapters detail vegetable-rich feasts and meatier dishes ideal for family or company: djej mahshi (chicken stuffed with spiced rice); shakriyah (spiced lamb and yogurt stew); clay pot shrimp scented with garlic and dried dill in the style of Gaza; and dinner party centerpieces such as stuffed squid in arak-spiked tomato sauce.

Equally compelling are the essays that frame each section of the book. She writes forthrightly of her family’s immigrant experience and the nuances of isolation, assimilation and resistance she’s faced to achieve a sense of belonging. Part 1 opens with memories of summertime family visits to Los Angeles but segues to her grandmother’s exodus from Palestine in 1948 during the creation of Israel. A later piece details a family trip to Lebanon and her father’s ancestral home in Damascus, Syria, that lit her professional pursuit of baking. “I remember,” she writes, “the revelation that a bakery can spark life even in places where life had been most depleted. I knew then that my ancestors were trying to tell me something: my community back in California needed an Arab street corner bakery.” Yes, we did, and we needed this book too. —Bill Addison

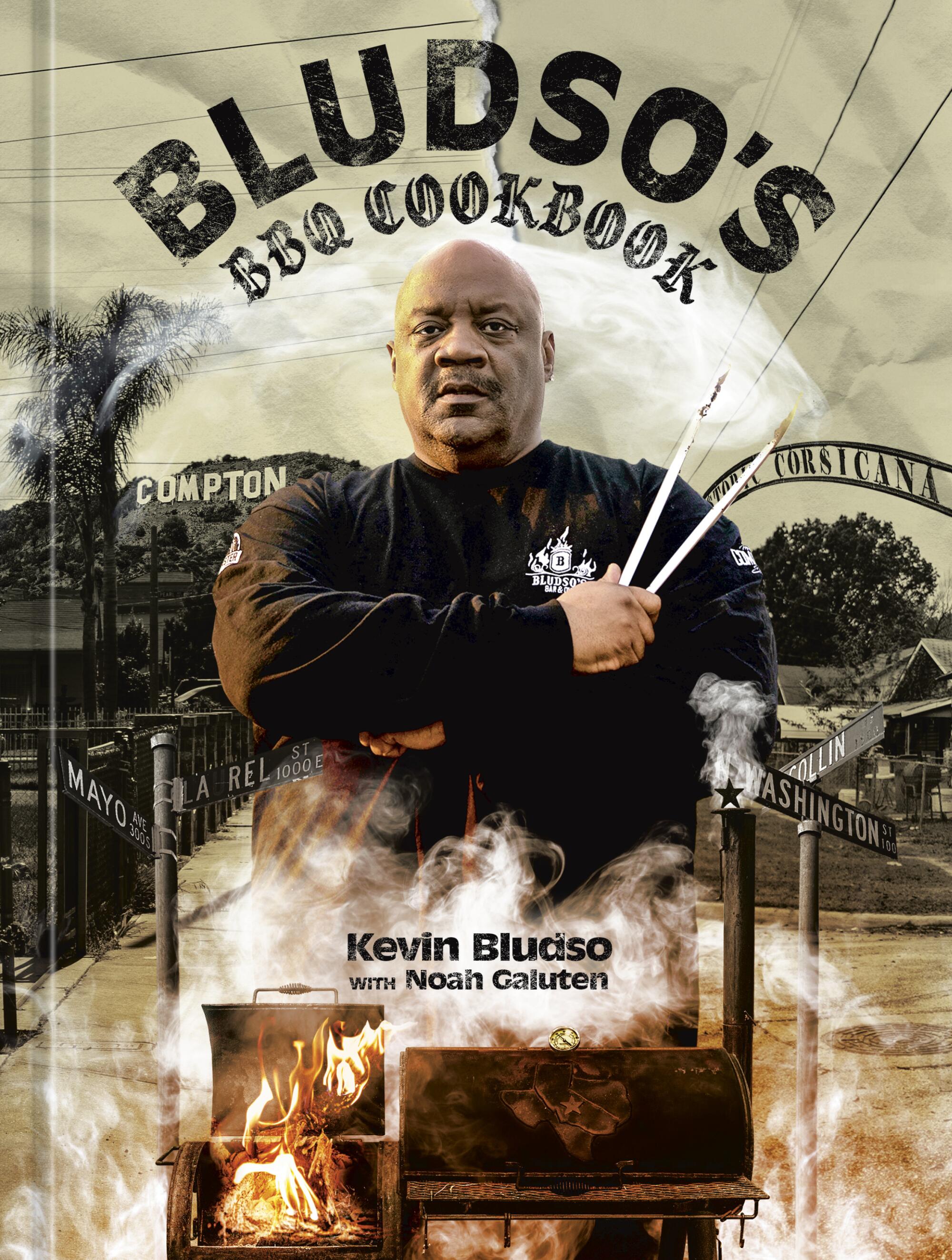

Bludso’s BBQ Cookbook: A Family Affair in Smoke and Soul

Kevin Bludso with Noah Galuten (Penguin Random House).

“Cayenne pepper, baby. If it ain’t hot, it ain’t me.” That’s Kevin Bludso transforming the usual pro forma pantry section of a cookbook into his own vivid expression of low-and-slow barbecue love. If you’ve ever eaten Bludso’s barbecue — either at his now-shuttered original spot in Compton or the thriving La Brea Avenue restaurant and bar — you know the value of the lessons in heat and smoke this legendary pitmaster has to offer in his memoir-style cookbook. Among them: Don’t disrespect the rub with wet meat; instead of a beautiful crust you’ll get lumpy, caked-on spices.

Bludso is a conduit for generations of barbecue know-how, mostly through the summers he spent in Corsicana, Texas, at the “illegal, bootleg BBQ stand” run by Willie Mae Fields, the great-aunt he called Grannie. He also learned from his mother, who Bludso says could barbecue better than his father, and his Uncle Kaiser and Aunt Beulah.

“I don’t want the BBQ in this book to be like some kind of damn algebra class,” Bludso writes. “BBQ is supposed to be fun. … Just don’t make bad BBQ.” Consider Bludso’s brisket recipe, which is detailed and authoritative, but includes the less-exacting “‘If You Get Drunk and Go to Bed’ method.”

In addition to the barbecue recipes, Bludso includes his take on soul food classics, from fried chicken through bourbon-pecan bread pudding, along with original recipes that reflect his dual Texas and Los Angeles identities. Consider his smoked oxtails birria, which combines his love of oxtails (don’t miss his recipe for spicy curried oxtails) with his love of menudo and birria. So delicious and so L.A. —Laurie Ochoa

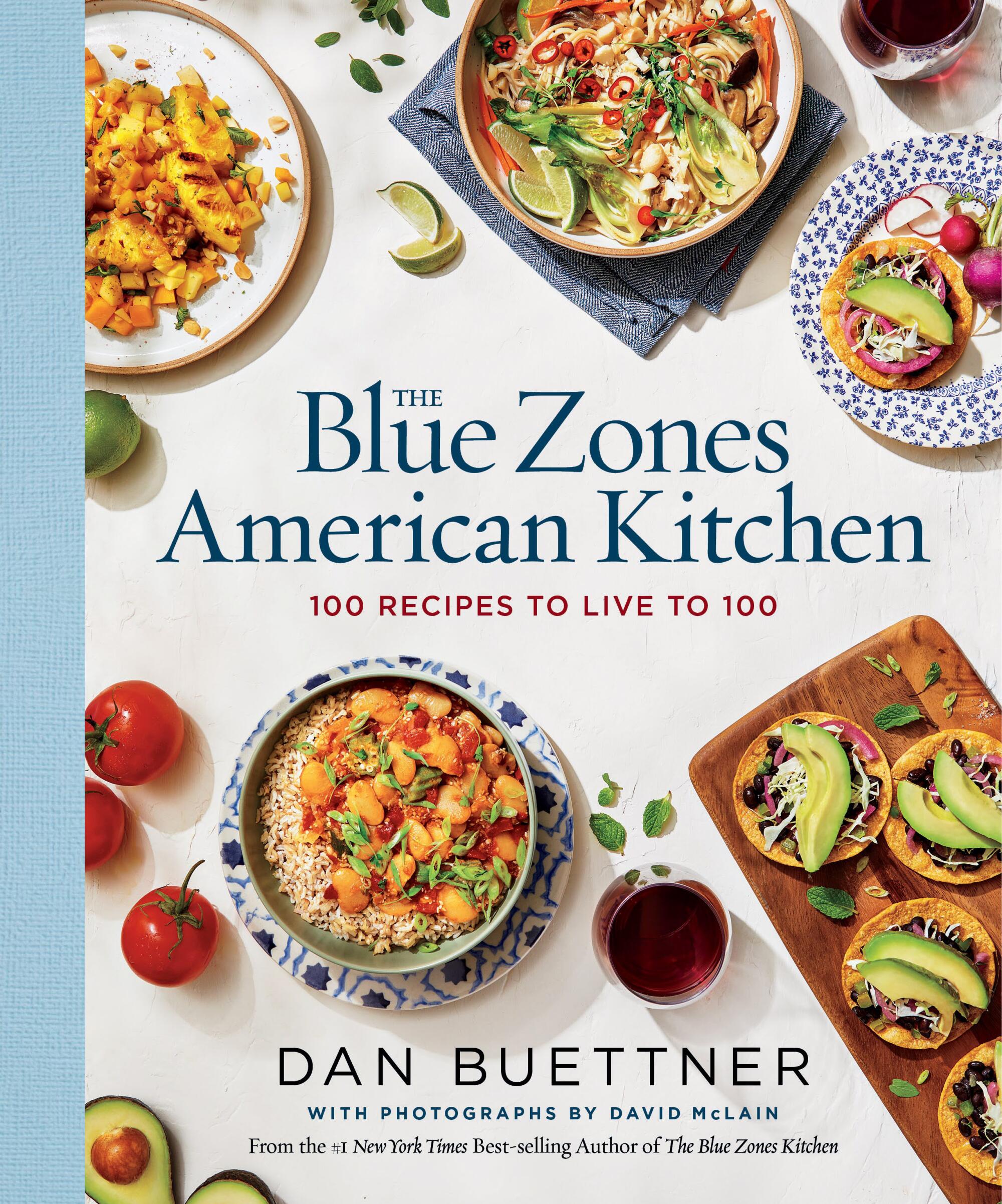

The Blue Zones American Kitchen: 100 Recipes to Live to 100

Dan Buettner (National Geographic).

Dan Buettner has spent the last 20 years studying and writing about Blue Zones, where he reports that people live longer and with less disease than anywhere else in the world. One key finding in his research is that long-lived people eat remarkably similarly all over the world. Among the books he has published on the topic was “The Blue Zones Kitchen,” which documented foodways of the Blue Zones communities and provided recipes from each. Turning his attention to finding Blue Zones in America, Buettner discovered four American food traditions that match the diet of longevity that he found in the six Blue Zones around the world. “The Blue Zones American Kitchen” details those findings and offers 100 recipes that reflect them.

We meet chefs, culinary historians and home cooks from Indigenous, Native and Early American, African American, Latin American and Asian American culinary traditions as well as from regional and contemporary American culinary practices. Their diets are largely plant-based (90 to 100 percent so in Blue Zones). They rely heavily on beans — which, in Blue Zones are eaten in some form every day — and an impressive variety of vegetables, including plenty of leafy greens. Animal products such as meat, dairy and eggs are used sparingly, more as condiments than as primary ingredients. In the Blue Zones, they consume very little sugar, and breads are made from whole grains and fermented leavening agents rather than yeast.

Recipes such as Three Sisters Cherokee succotash, butter beans with benne seeds and okra, and bean thread noodles with bok choy and shiitake mushrooms will not only make for fabulous meals but might also help you live longer. —Julie Giuffrida

Cooking With Mushrooms: A Fungi Lover’s Guide to the World’s Most Versatile, Flavorful, Health-Boosting Ingredients

Andrea Gentl (Artisan).

Photographer Andrea Gentl might best be known for her images — lush, award-winning pictures of food, chefs and faraway places. She’s also an avid cook, and “Cooking With Mushrooms” is the first cookbook she has written (definitely not the first she has photographed).

“I rediscovered the untamed and varied world of mushrooms — the diverse, healthy, adaptogenic magic mycelia of the fungi kingdom — through photography,” writes Gentl. “I have always been a bit obsessed with mushrooms.” If you’re obsessed with mushrooms too (who isn’t, really?), then this book is for you. I love the photos in the “Mushroom Varieties” section that celebrate their glorious shapes and colors, close-ups of all the curves and dimples of the gills and caps that make them uniquely mesmerizing — from beech to woodear.

The epicenter of L.A.’s mushroom boom is a 34,000-square-foot warehouse in Vernon, where Smallhold ramps up to grow more than 20,000 pounds a week.

Somewhat surprising is the large variety of recipes — all the ways you can cook (and bake) with mushrooms. Sure, there’s a mushroom frittata and soft-scrambled eggs with shaved truffle. But also mushroom rose cardamom rye granola; pesto made with maitake, lovage, walnuts and pistachios; and an endive wedge salad with crispy shiitake “bacon.” I’ve made mushroom carnitas with lion’s mane, but I especially like Gentl’s version with oyster mushrooms and cauliflower and lots of lime and chile and a little fish sauce. The brown butter mushroom cakes are extra ‘shroomy because they’re made with lion’s mane mixed with a miso mushroom paste. Roast chicken with miso mushroom butter? Yes, please. Mushroom ragu? Also yes. Double-chocolate tahini mushroom brownies? Why not? —Betty Hallock

Delectable: Sweet & Savory Baking

Claudia Fleming and Catherine Young (Random House).

To say that Claudia Fleming’s first book, “The Last Course,” which came out in 2001, changed the art of pastry in America over the past two decades wouldn’t be an overstatement. Nearly every pastry chef and recipe developer I know, including myself, counts it in the top 3 cookbooks that influenced their craft — ask them which of her recipes is their favorite from the book because I guarantee they’ll have one (it’s the baked butterscotch custards with coconut cream for me). So I was excited when her highly anticipated second book, “Delectable,” finally came out a couple months ago. In it are all the techniques that made “The Last Course” such an indispensable resource, but now with updated flavor combinations and more recipes geared toward home bakers and cooks. A fennel tea cake with Pernod whipped cream is classic Fleming — an inspired flavor combination that updates a standard everyone can love — allowing the anise-y, bitter aromas of fennel seeds and grapefruit zest to perfume and balance a rich, sweet cake. Her roasted pears with maple and goat cheese cream is another shining example, the fruit’s flavor condensed and enhanced with fresh ginger and bourbon, while a sprinkling of maple-sugared pecans adds crunch and sweetness to balance a tangy ghost cheese cream. It’s a fancy restaurant dessert idea made simple and elegant for home cooks. It, and the rest of the book, cements her place as one of the best dessert makers alive. —Ben Mims

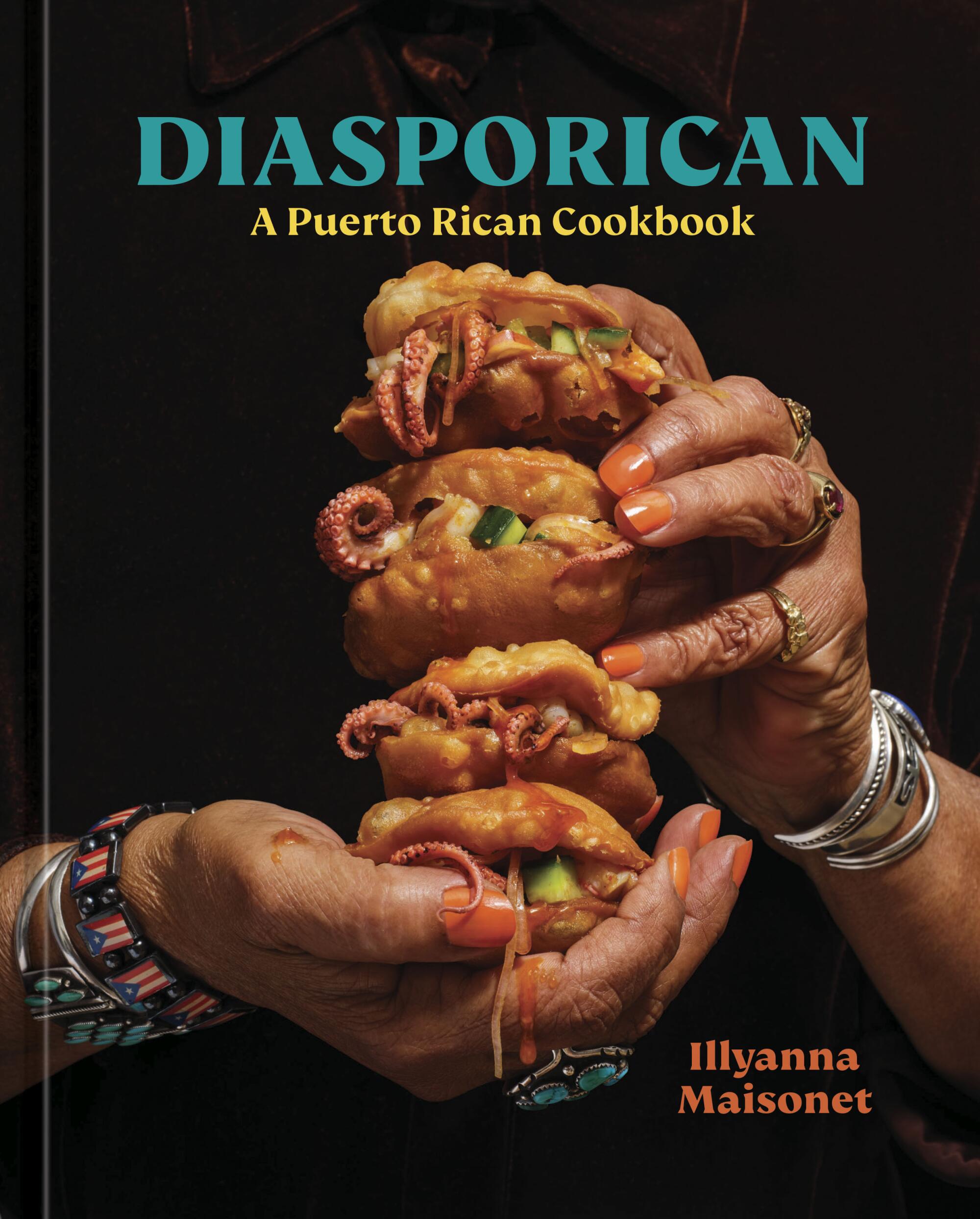

Diasporican: A Puerto Rican Cookbook

Illyanna Maisonet (Ten Speed Press).

Illyanna Maisonet penned a column called Cocina Boricua for the San Francisco Chronicle, writing about food of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Her book “Diasporican” is a culmination and continuation of research and collected recipes, preserving foodways that might otherwise be lost or overlooked. “No one seems to know anything about Puerto Rican food,” she writes. “Sometimes not even Puerto Ricans.”

Having grown up in Sacramento, she calls her own cooking style Californian-Puerto Rican, or Cali-Rican — built on the flavor lexicon that comprises the opening chapter of her book: achiote oil, the spice mix sazón, a sofrito with lots of cilantro and culantro (“like cilantro’s cousin who comes to visit from the hood … and possibly wearing FUBU”). The sofrito is fundamental; she uses it at both the start and end of almost every savory recipe, sautéing it as the flavor base for a dish and then adding it as a finish (“I treat it as I would pesto”).

Some are traditional or family recipes, and some are made her own, like guanimes — dumplings that are traditionally steamed in plantain leaves and served with tomato sauce and bacalao — where she uses Dungeness crab instead of the salted fish. Others are traced to Puerto Rican communities as far away as Hawaii, such as pastele stew served over rice and topped with an egg, loco moco style. Nina DeeDee’s beans are lately my go-to Sunday one-pot — made with just five ingredients, including copious amounts of cheese.

Maisonet tells stories that are visceral and transporting and occasionally provide glimpses into the interior lives of a daughter, mother and grandmother — generations linked through food. She takes on colonialism, identity and culinary history, threaded with intimate personal stories — sometimes of struggle, sometimes of joy. For a book dedicated to “the tribe of Ni De Aquí, Ni De Allá (‘not from here, not from there’),” it reads like home. —B.H.

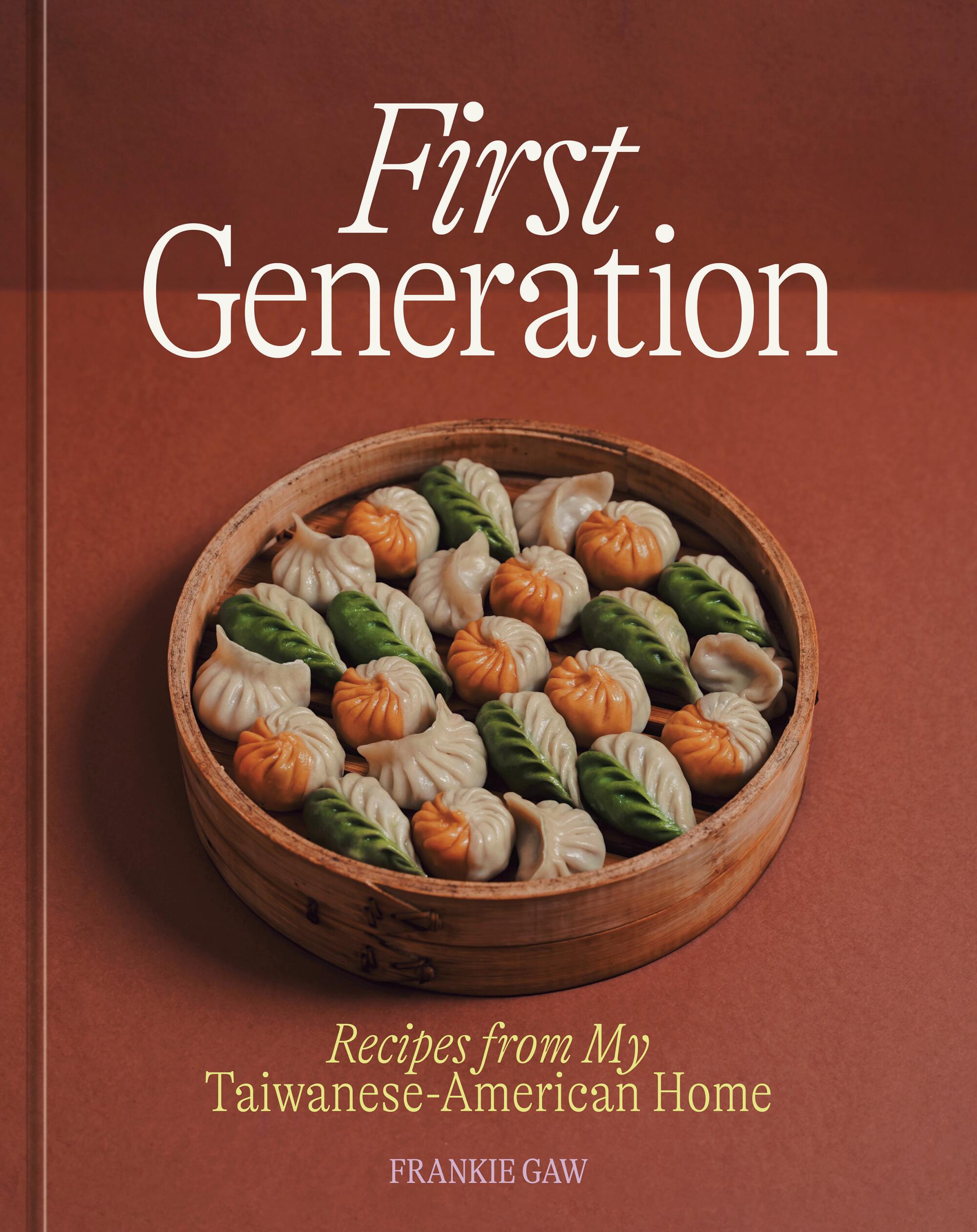

First Generation: Recipes From My Taiwanese-American Home

Frankie Gaw (Ten Speed Press).

Frankie Gaw pulled off one of the toughest balancing acts in the cookbook genre: publishing a mouthwatering set of recipes along with thoughtful and engaging backstories. The food writer and photographer of popular blog Little Fat Boy uses “First Generation” to further explore his Taiwanese American identity, an existential blend of pride, shame, exaltation, self-doubt, acceptance, curiosity and love spread across generational recipes that revere Taiwanese cuisine, and those informed by his life as a first-gen immigrant growing up in the Midwest suburbs where the most cherished family dinners out were spent at Olive Garden.

Step-by-step photo series and hand-sketched diagrams illustrate exactly how to achieve the perfect springiness in hand-pulled noodles, the flaky spirals of a pancake, and the recipes themselves span not only Gaw’s experience but those of his parents and grandparents: The crepe-like dan bing his grandmother would make for him as a child, regaling him with tales of Taipei’s breakfast shops, say, or the night-market popcorn chicken beloved by his mom and dad before their move to America. If Gaw’s family ties to Taiwanese cooking are the heart of this book, then that move to America is the backbone of its thesis: recipes that seamlessly blend both worlds with dishes such as a Costco-corn-dog riff — here stuffed not with hot dog but lap cheong — and Big Macs packed not with beef patties but one made from lion’s head meatballs. There’s a game-day-inspired scallion pancake ode to nachos, as well as a take topped with ancho-chile-and-hoisin-cooked pork shoulder in reverence to all the suburban Chipotles and San Francisco taquerias he’s loved before.

We’re given vignettes and conversations with family members we should feel lucky — and almost voyeuristic — to witness: a Thanksgiving conversation with his grandma, whose fading memory can’t keep our author straight with his older cousin but is still sharp enough to recall the ingredients necessary for soy eggs and steamed bao, and Gaw’s heart-wrenching coming-out letter penned to his father, who’d long since passed. “I cook scallion pancakes to remember the sound of your voice,” he writes, “even though it makes me want to cry.” “First Generation” is a deeply personal reflection on where Gaw fits within the diaspora and within his own inner monologue; I’m not ashamed to admit it made me tear up. It also made me ravenous. —Stephanie Breijo

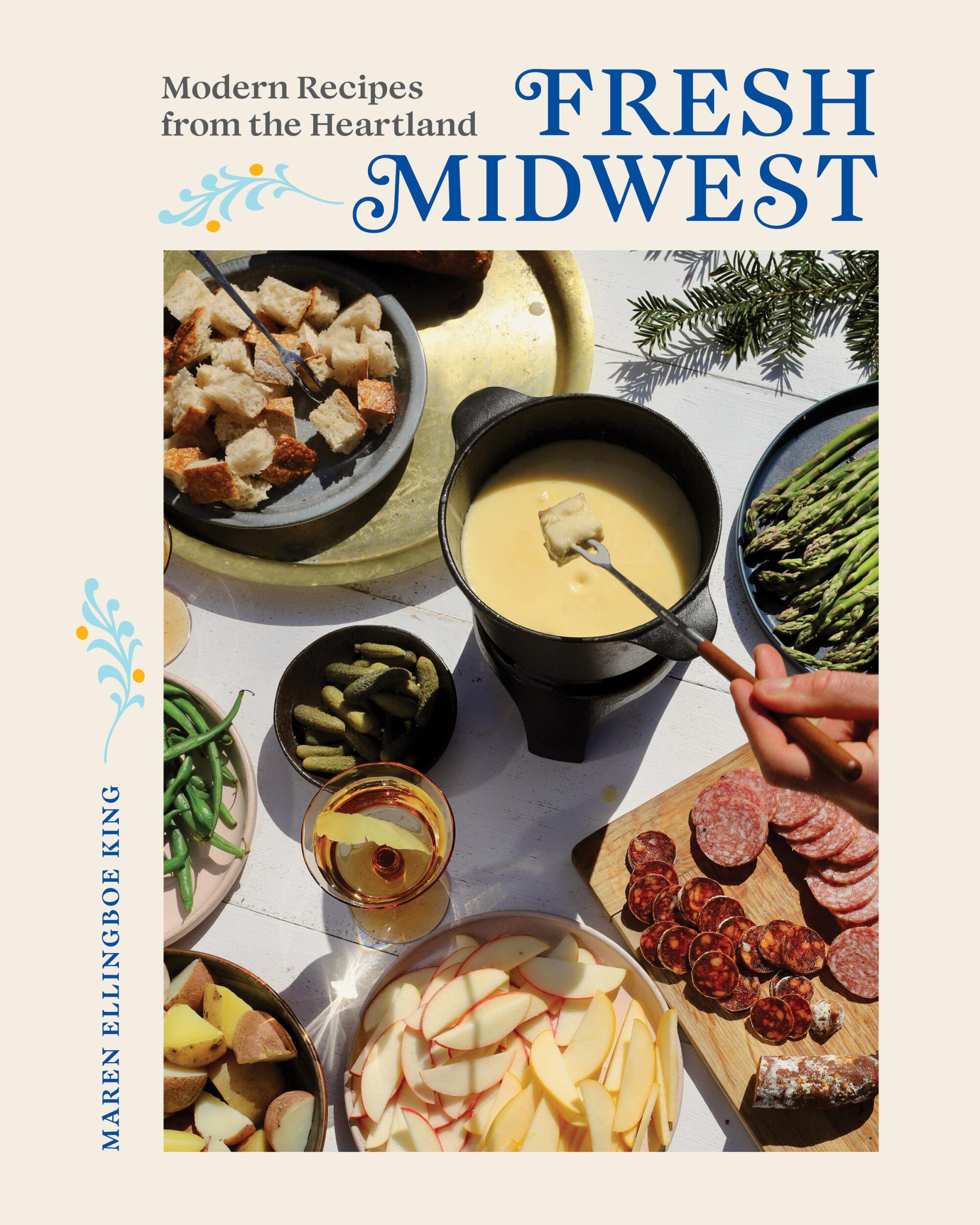

Fresh Midwest: Modern Recipes from the Heartland

Maren Ellingboe King (W.W. Norton).

Maren Ellingboe King’s take on Midwestern cuisine brushes off the convenience food kitsch in favor of honest-to-goodness home cooking that speaks to a region of the country steeped in more diverse culinary traditions than it gets credit for. She incorporates gjetost, a Norwegian cheese that tastes like toasted white chocolate, into a macaroni and cheese recipe that is now in my regular rotation for dinner parties. A spoonful of instant oatmeal adds moisture to her recipe for Swedish meatballs that are the best I’ve ever tried. And her recipe for cardamom coffee buns in “Fresh Midwest” is inspired, taking the traditional Swedish breakfast pastry and adding coffee to the dough and filling to both enhance and help ground the heady floral aroma of the cardamom. Her perspective is fresh and approachable, while still keeping the nostalgia of her family’s recipes intact. —B.M.

Food52 Simply Genius: Recipes for Beginners, Busy Cooks & Curious People

Kristen Miglore (Ten Speed Press).

Compilation cookbooks can, ironically, often suffer from a lack of a theme beyond a loose naming conceit. However, “Food52 Simply Genius” by Kristen Miglore is not one of them. Each recipe hinges on a brilliant but simple hack or flavor twist that instantly makes you want to earmark the page for every recipe to make in the future. Some twists are all about a technique that makes you wish you had thought of it first, like Maria Speck’s shortcut polenta that calls for soaking the polenta overnight so that the actual cooking part takes a dozen minutes instead of an hour. And in Dana Velden’s fluffy buttermilk pancakes, un-beaten egg whites add stability and texture instead of the typical whipped egg whites, saving you time and a sore arm. But my favorite hacks are those that rely on inspired flavor combinations, like Bryant Terry’s use of oven-dried tomatoes to add umami edge to a pan of vegan collard greens, or how Ignacio Mattos adds provolone to a raw fennel salad to balance its lean edge. Whichever recipe you choose to take on, you’ll learn something new about cooking that you didn’t before — and those are the types of books you want on your shelf forever. —B.M.

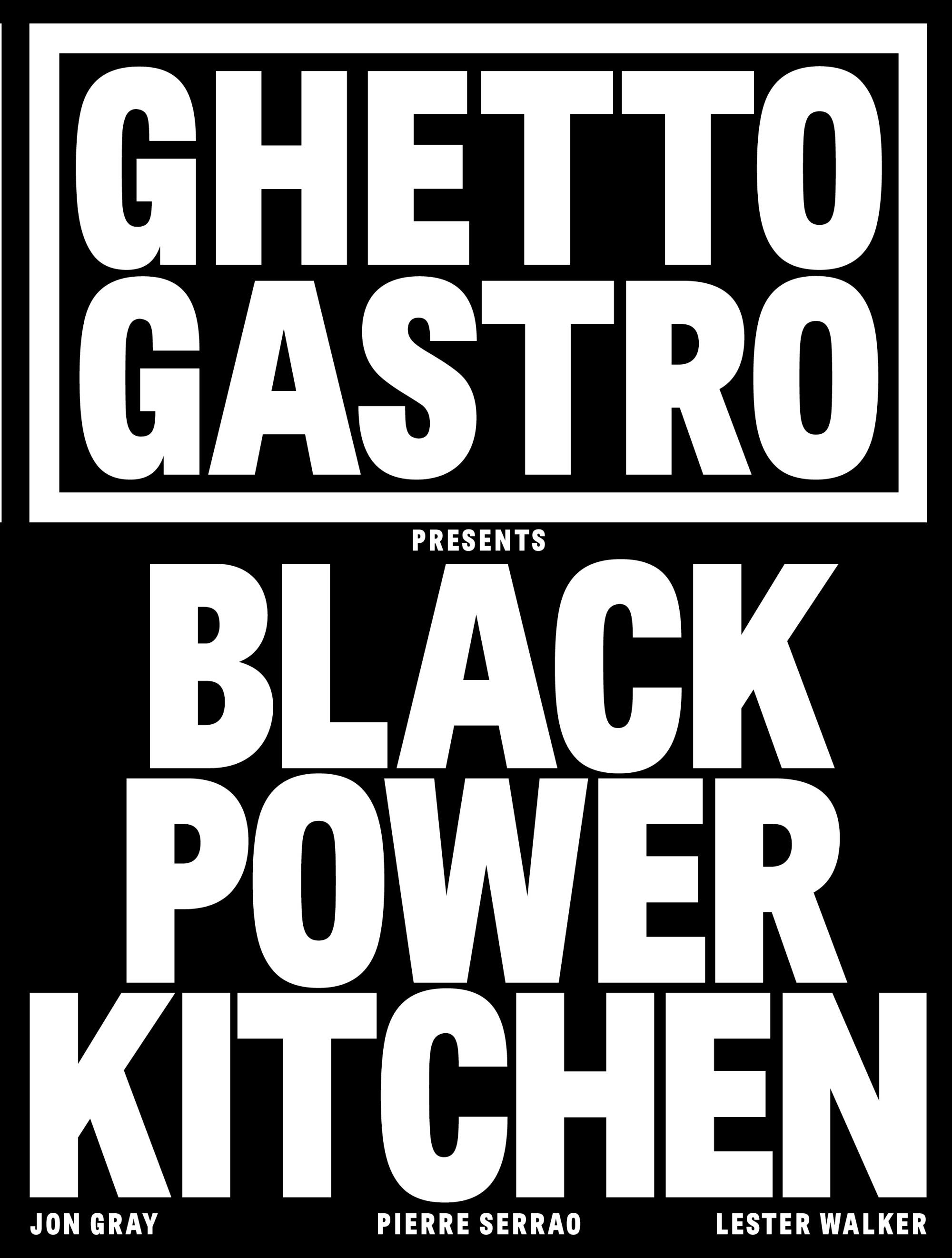

Ghetto Gastro Presents Black Power Kitchen

Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao and Lester Walker with Osayi Endolyn (Artisan).

Food is power. Food is politics. Food is not merely nourishment but collective experience that relies on history, context and identity. You may already be familiar with some of these concepts, but “Black Power Kitchen,” from the self-described culinary collective Ghetto Gastro (Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao and Lester Walker) and Osayi Endolyn, elevates these ideas to the next level with their first cookbook. The book covers so much ground, it’s hard to know where to begin. There’s the part that’s a love letter to the Bronx, the home of Gray and Walker; there are frank discussions of the realities of racism and the Black experience in America; there are evocative photos from Nayquan Shuler and Joshua Woods and other mixed media from artists like Hugo McCloud, Ludovic Nkoth and Alvin Armstrong. And naturally, there are recipes: feijoada, which Jessica B. Harris (who writes the book’s foreword) credits to enslaved Africans in Brazil, Caribbean dishes (Serrao has Bajan roots) and naturally, a take on the essential Bronx sandwich, the chopped cheese. It’s plant-based, like many recipes in the book, in a nod to the long history of plant-based eating among the peoples of African diaspora. —Lucas Kwan Peterson

Good & Sweet: A New Way to Bake With Naturally Sweet Ingredients

Brian Levy (Avery).

Baking without white granulated sugar seems almost impossible. The ingredient forms the very foundation of the craft. It’s such a tough topic to tackle, most people don’t bother. Or if they do, the results are always less than stellar. That’s why I was so excited to read through Brian Levy’s “Good & Sweet” dedicated to baking with no refined sweeteners. He approached the subject not in the usual diet-focused way that robs the practice of any joy, but instead looks at using naturally sweet ingredients like dates and coconut and shows how to manipulate them to focus on their sweetness, improving the more traditional dishes in the process.

Freeze-dried pineapple lends its bright, sour-y sweetness to a buttery poundcake; dried apples sweeten a blueberry pie filling, while fresh corn is a genius way to sweeten whipped cream for the pie. But his Derby Date Pie was my favorite, adding dates to the triad of pecans, chocolate and bourbon to sweeten it with a gooey, caramel sweetness that fits the dessert perfectly. His recipes produce desserts and cookies that are so delicious without refined sugar, it’s proved for me that sugarless baking can still be just as sweet. —B.M.

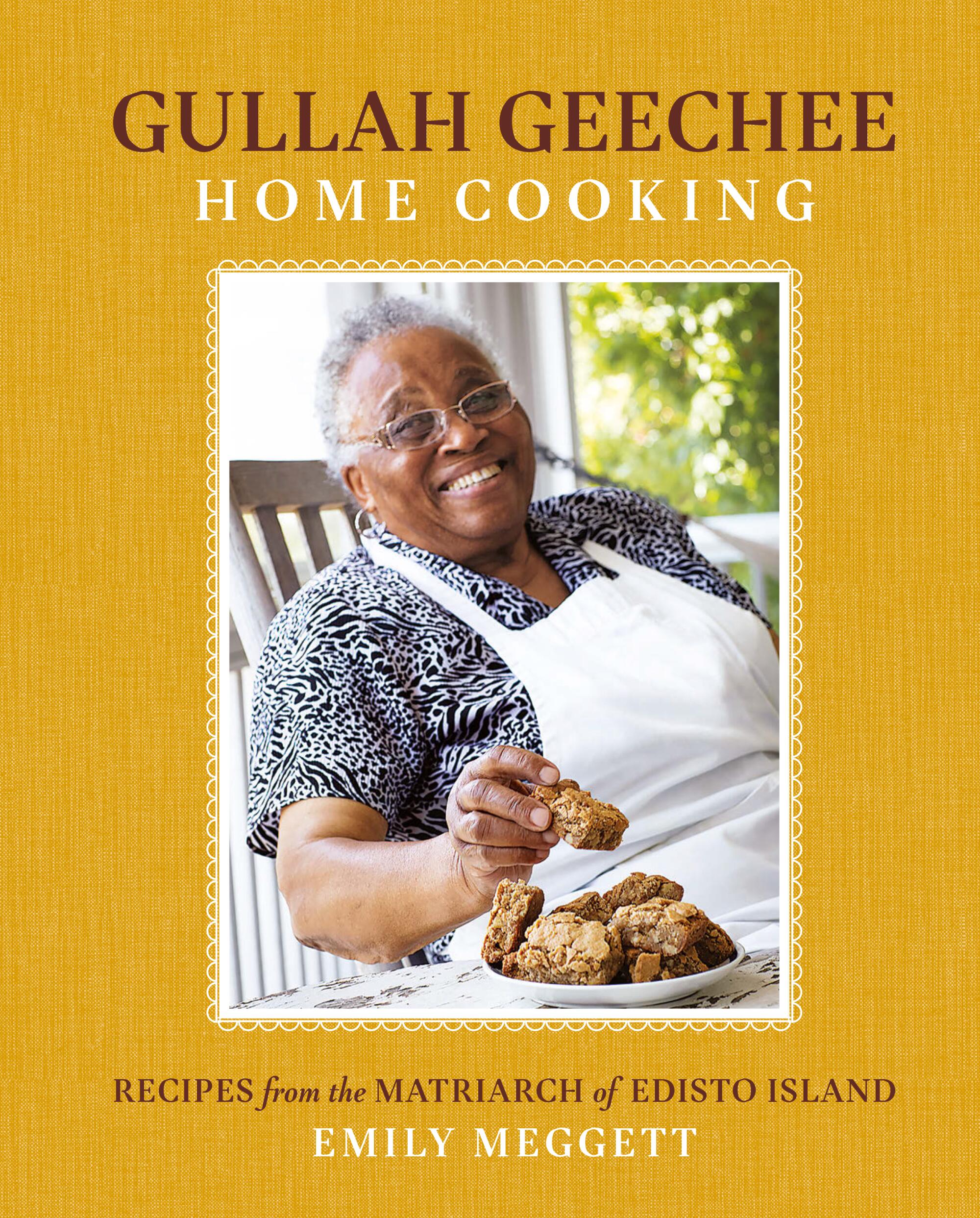

Gullah Geechee Home Cooking

Emily Meggett with Kayla Stewart and Trelani Michelle (Abrams).

A few years ago, I spent a memorable day with Emily Meggett, known affectionately as Miss Emily, in her home on Edisto Island, just southwest of Charleston. It was a day of pure warmth and joy, of cooking, education and community. The 90-year-old Meggett is known as the matriarch of Edisto, its protector and advocate, and perhaps the foremost expert on Gullah Geechee cooking, the cuisine of the descendants of enslaved Africans who settled on the coastal areas and islands of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida. Meggett, together with Kayla Stewart and Trelani Michelle, gives us a collection of hearty, homey recipes like a one-pot red rice with fried salt pork, corn fritters, oyster stew and one I was lucky enough to witness her make in person, stuffed fish with parsley rice. “When I first started cookin’,” Meggett says in her book, “Gullah Geechee Home Cooking,” “I made $11.13 per week. Now you’re reading my cookbook. Ha! Ain’t that somethin’?” Yes, it certainly is. —L.K.P.

Justice of the Pies: Sweet and Savory Pies, Quiches and Tarts Plus Inspirational Stories From Exceptional People

Maya-Camille Broussard (Clarkson Potter).

My favorite cookbooks bring me into the kitchen with the authors. Maya-Camille Broussard’s book “Justice of the Pies” makes me feel like I’m sitting at a stool in her kitchen, listening as she recounts the story of how she started her Chicago bakery after her father died.

Inspired by his love of pie and his life’s work as a criminal defense attorney to better people’s lives, Broussard’s bakery hosts “I Knead Love” workshops where she helps elementary-aged children from low-income communities learn basic cooking skills and nutritional development to fight food insecurities. In addition to the recipes she’s known for at the bakery, she introduces dishes inspired by “stewards” who are on similar missions for good, such as Tanya Lozano, co-founder of Healthy Hood Chicago; Seema R. Hingorani of Girls Who Invest; and Paige Chenault of the Birthday Party Project.

Cinnamon, nutmeg and ginger spice canned pumpkin in this classic Thanksgiving pie recipe. Blind-baking the crust ensures a crisp pastry to contrast the smooth custard filling.

She shares recipes for her most celebrated bakes, including the salted caramel peach pie, a closely guarded secret until now. It’s more of a pie-cobbler hybrid, with a filling made from canned peaches, butter, sugar, eggs and oats. You drizzle a salted caramel sauce over the top, making it extra decadent. I recently made it for my picky family, who declared it one of the best pies they’d ever eaten. Broussard’s shepherd’s pie was just as rewarding, with a rich beef filling under a blanket of fluffy mashed potatoes. Though some of the recipes include multiple homemade components, directions are easy to follow and her ingredients are accessible. And by the end of the book, I felt like I’d made a new friend. —Jenn Harris

Masa: Techniques, Recipes and Reflections on a Timeless Staple

Jorge Gaviria (Chronicle Books).

Several years ago, I took on making masa from scratch, soaking corn kernels in calcium hydroxide to break down their outer kernels — a process called nixtamalization — then grinding them into a dough to make tortillas. The resulting tortillas were crumbly and chewy, and while I didn’t have success with them, I did have a newfound appreciation for the art of working with masa. And while I have used a reliable bag of Maseca throughout my life to make tortillas, it wasn’t until I tried Masienda’s masa that my cooking changed for the better.

In “Masa,” founder Jorge Gaviria recites the history of the staple and, in excruciating detail, how to make it for yourself so that it actually comes out delicious. It’s in this book that I realized my fatal error: I didn’t boil the corn with the calcium hydroxide long enough. Armed with information, I tried the process again and found myself with fresh masa that produced the most intensely aromatic tortillas I’ve ever had. But with this newfound confidence came the permission to experiment beyond the tortilla. Memelas and huaraches, things I’d only ever ordered in restaurants, were now at my fingertips, literally. And blending the fresh masa with milk and coffee beans in Carlos Salgado’s coffee atole gifted me with my new favorite wintertime drink.

“Masa” is more than the essential history and record of an ingredient, it’s a gateway to exploration that allows Mexican culture’s arguably most important food to live and breathe in a new way for generations of cooks to come. —B.M.

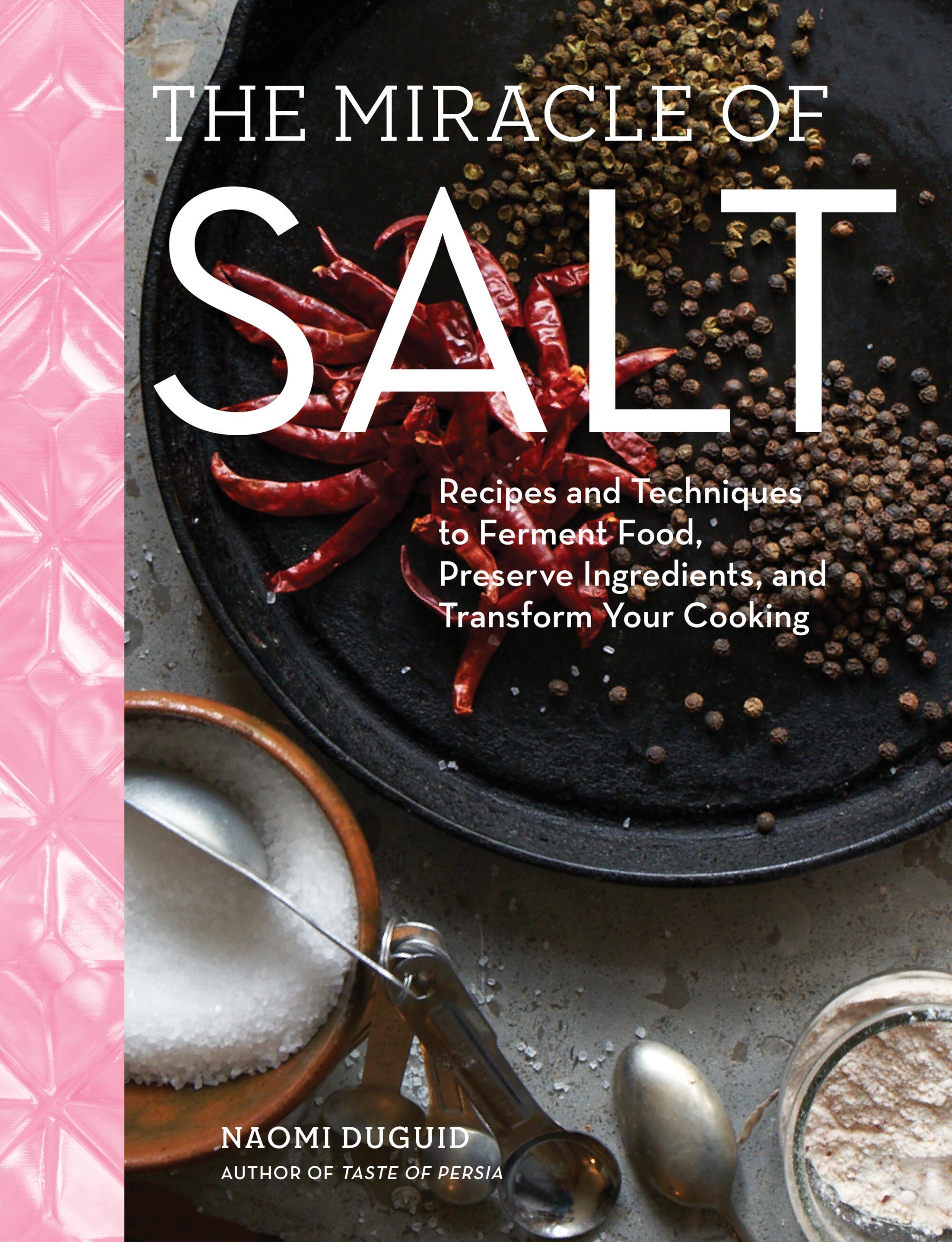

The Miracle of Salt: Recipes and Techniques to Preserve, Ferment, and Transform Your Food

Naomi Duguid (Workman).

I would follow Naomi Duguid to just about any corner of the world she was interested in exploring. The author and co-author of some of the food world’s most fascinating and authoritative cookbooks, from “Flatbreads and Flavors: A Baker’s Atlas” through “Taste of Persia: A Cook’s Travels Through Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and Kurdistan,” Duguid always brings her readers deep research on food culture and cooking, captivating stories of her travels and recipes that are well-tested and easy to follow. Pick up a copy of her newest book, “The Miracle of Salt,” and you’ll see what I mean. Certainly there have been other books on salt, notably Mark Kurlansky’s 2002 exhaustive history. But Duguid brings us original research and a cook’s perspective on the ingredient most of us take for granted.

The “salt larder” section of her book, with simple recipes for things like Acadian salted scallions, salted shiso leaves and spiced green mango pickle will give any level of cook a whole new set of go-to flavorings to wake up even the most basic weeknight supper. In the second half of the book, she takes us around the world with meat, fish, vegetable, sweet and more recipes that illustrate the many different ways salt and salt-based condiments (fish sauce, miso) are used in different cuisines. With Duguid’s guidance, you’ll not only make a delicious dinner, you’ll have a great story about the ingredients to tell your guests. —L.O.

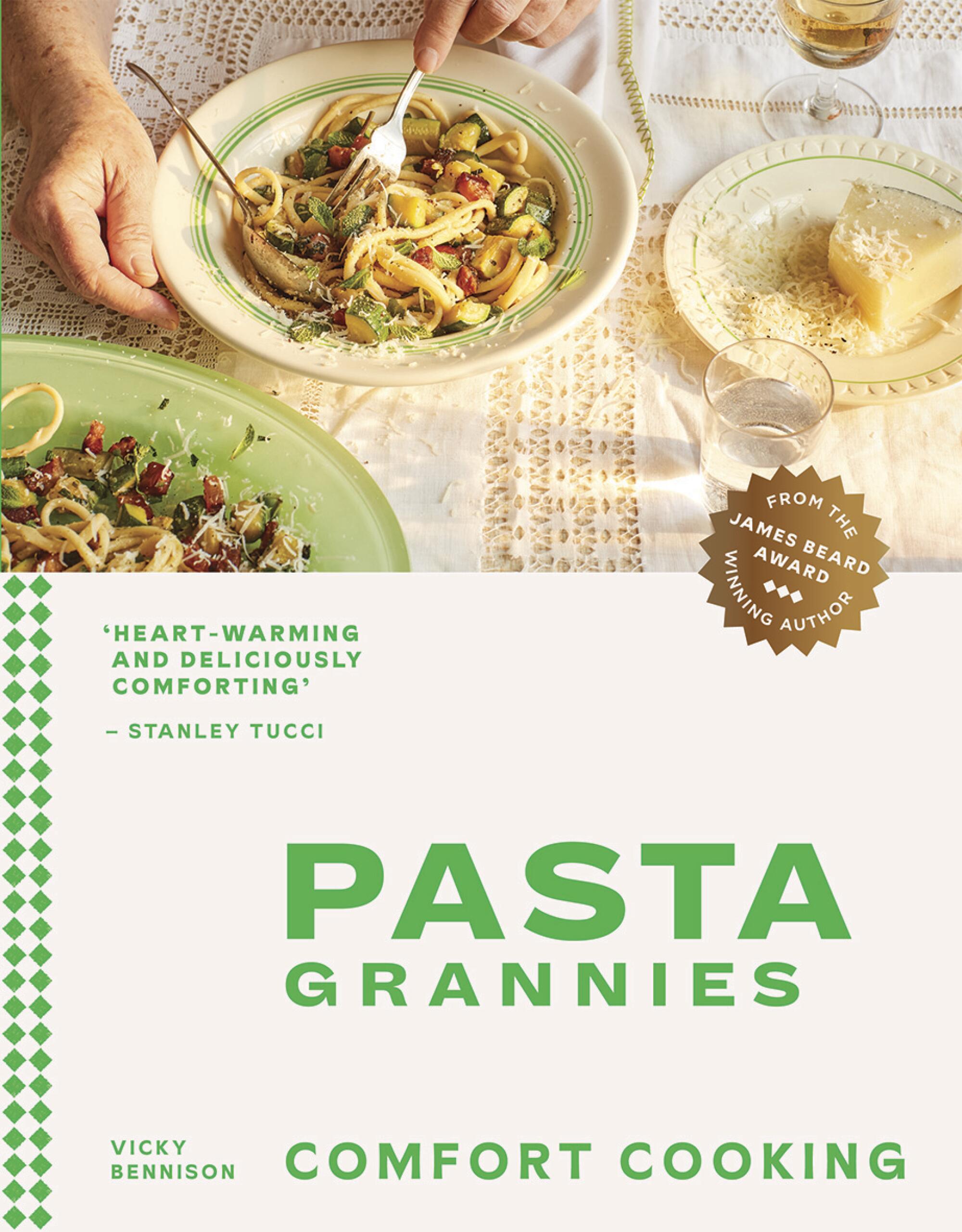

Pasta Grannies: Comfort Cooking

Vicky Bennison (Hardie Grant Books).

In 2014, food and travel writer Vicky Bennison unveiled what began as a passion project but what soon took over her life: “Pasta Grannies,” a YouTube channel devoted to generational Italian cuisine and the methods fast disappearing from home kitchens. Originally the author and producer hoped to document every shape and form of pasta, but as she traveled Italian countrysides and cities to document, she soon realized the real stars weren’t the shapes and the doughs but the pasta grannies themselves. A terrific 2019 cookbook brought five years of recipes from our phone screens onto the page, but this fall the followup “Pasta Grannies: Comfort Cooking,” dedicated to rustic but artful comfort foods, brings us even closer to these nonne.

While the focus remains on pasta, Bennison incorporated recipes pulled from dozens of “Pasta Grannies” videos she deemed most comforting, this time expanding her cookbook to include chapters on pizza, rice and dessert in addition to pastas baked, boiled or otherwise. Much like the first volume the dough tome begins with a quick primer on crafting pasta by hand: what tools you’ll need, basic troubleshooting, a quick guide to flour, cooking tips and suggested ingredients. From there, we’re off and running through bowls of chestnut gnocchi; risotto-stuffed tomatoes in the Roman style; fried ravioli plump with foraged greens; the North African-influenced frascatole, served here with lobster; and fried poppy-seed fritters packed with milk, honey and breadcrumbs.

You’ll follow the grannies as they forage for porcini in the hillsides, snip squash tendrils from a secret garden in Sicily and shell large speckled cranberry beans at the end of harvest season, and you will cut, roll, knead and form pasta dough in methods taught by some of the sassiest grannies ever committed to print/video. Perhaps the most ingenious facet of this sequel — and one so useful it’s a marvel it isn’t included in all books linked to ample online content — is the addition of QR codes at the corner of every recipe. With the simple opening of your phone’s camera you’ll be taken to the recipe’s corresponding “Pasta Grannies” episode on Youtube, the method laid out in video form, the nonne come to life. It’s a true marvel these methods and recipes are preserved, and with Bennison’s latest cookbook, she makes accessing, visualizing and knowing these Italian grannies and their kitchen secrets all the more effortless. —S.B.

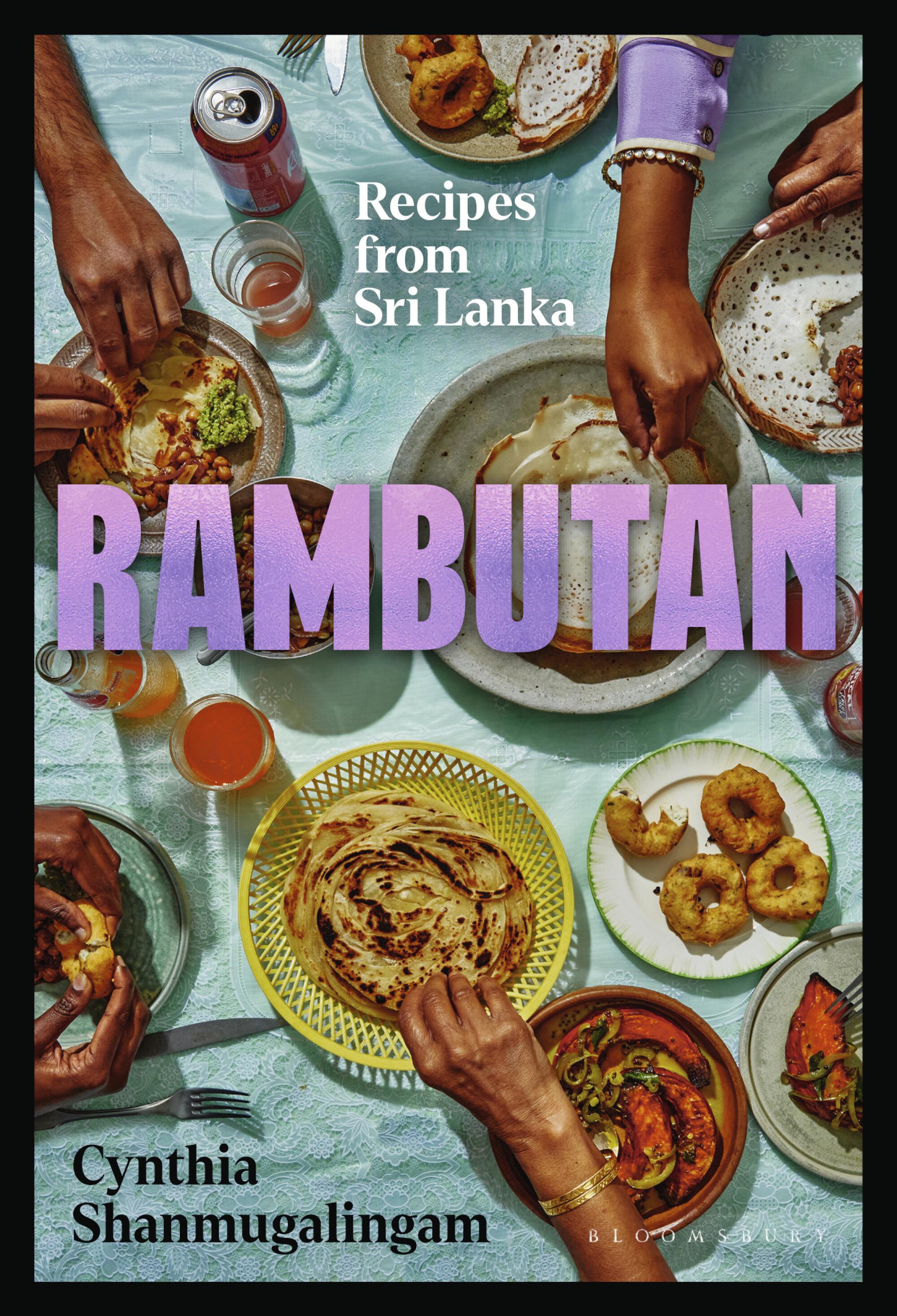

Rambutan: Recipes From Sri Lanka

Cynthia Shanmugalingam (Bloomsbury Publishing).

All cookbooks are narratives carried by recipes, but Cynthia Shanmugalingam is an especially enthralling storyteller. Even before I flipped through the first chapter on vegetables and fruits — eyeing the roast pumpkin curry, the coconut dal with kale and the potatoes fried with turmeric and flurry of other spices — I felt the gravitational pull of her writing about her native Sri Lanka and its delicious, conflated foodways.

“‘Rambutan’ is the story of an immigrant kid in England trying to cook her way out of the profound sense of loss about the place her parents called home,” she establishes in her introduction. A few lines down, she cautions, “Warning: I have not shied away from the country’s often painful history of war, colonial oppression, slavery, spice trading, poverty and proselytizing in the pages.”

Like so many defining works of the cookbook genre, Shanmugalingam’s gorgeously photographed tome melds memoir, history, journalism and instruction into a seamless literary hybrid. Among nine shorts on Sri Lankan culinary culture, one of them offers pointed words on a disputed term: “Listen up curry deniers: curry is a word, it a Tamil word, it is used by at least 69 million Tamil Indians and three million Tamil Sri Lankans and the word is over 3,000 years old … Curry means a lot of different things in poetic Tamil: Just like the dish itself, it is a shape-shifting, magical thing.”

By the time I reached a piece on Sri Lankan Muslim street food that began, “In that refuge for drunk kids and insomniacs that is the Hotel de Pilawoos in Colombo …” I was searching online to see if there was an audio version of “Rambutan” I could listen to while making Shanmugalingam’s cardamom-scented watalappan tart. There isn’t, but there should be. —B.A.

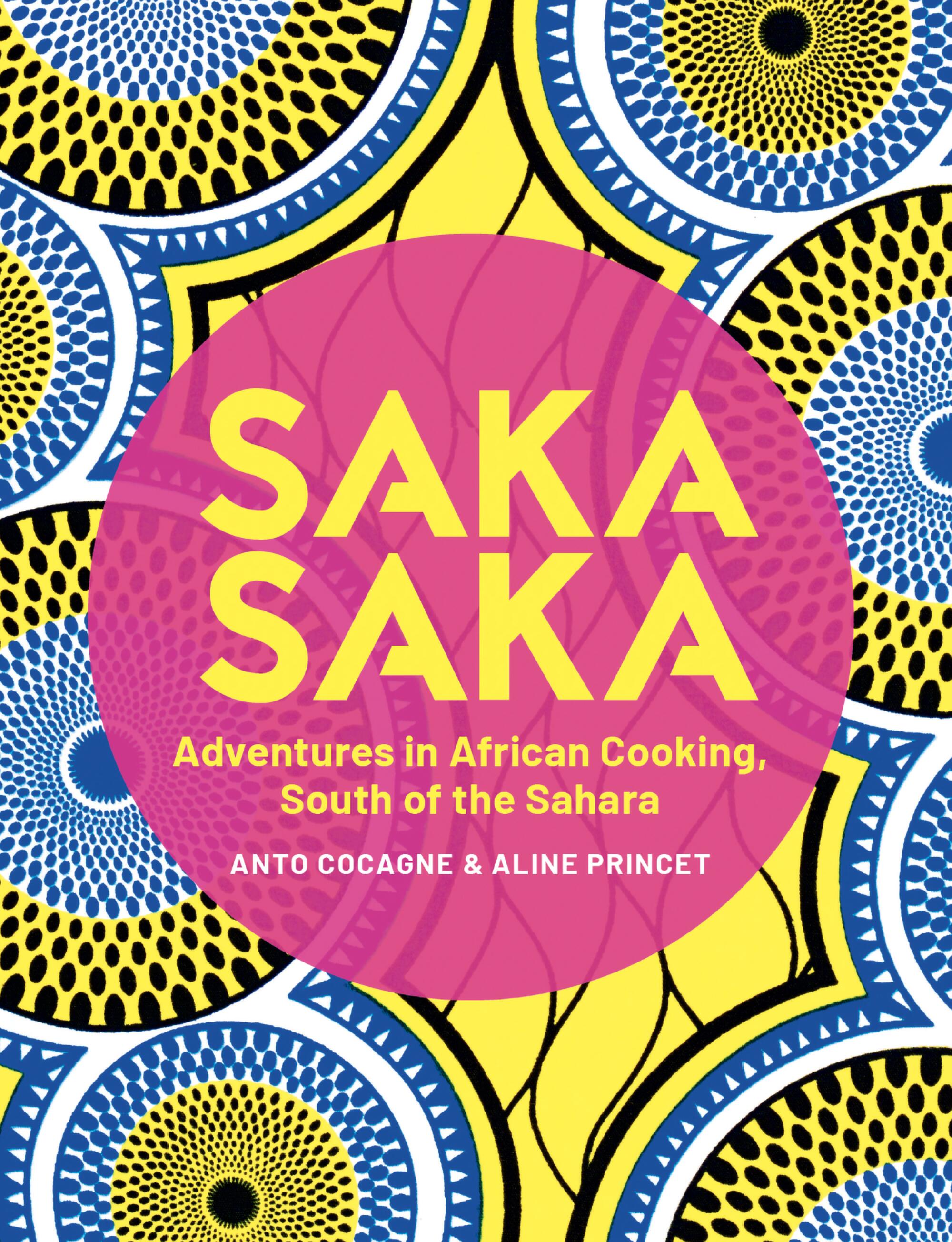

Saka Saka: Adventures in African Cooking, South of the Sahara

Anto Cocagne and Aline Princet (Interlink Publishing).

“Why is African culture largely missing from the Western culinary canon, considering the intercontinental gastronomic explosion of recent years?” This is a question photographer Aline Princet asks in her foreword to “Saka Saka: Adventures in African Cooking, South of the Sahara,” an important and enchanting cookbook by Anto Cocagne. The French-born and Gabon-raised chef sets out to reframe African cooking, which, as Cocagne writes, has “as many African cuisines as there are countries, cultures and dialects.”

In France, Cocagne has gained a measure of fame through her TV show, “Rendez-vous avec Le Chef Anto,” which focuses on the cooking of a different African country in each segment. “Saka Saka” extends the young chef’s reach to a global audience with stories and recipes that make you want to get cooking. Black-eyed pea and beet hummus, the Cameroon-style beef and plantain stew called beef kondré, Senegalese yassa chicken and a fantastic dessert of spiced pineapple with cassava crumble are just some of the recipes worth exploring.

Accessibility for all levels of cooking, including beginners, is important to Cocagne, who includes “easy” and “medium” rankings for each recipe; she is also keenly aware that some may have trouble finding certain ingredients, and supplies mail-order sources and suggested substitutions. Adding to the delight of this beautifully designed cookbook are Princet’s photos, not only of the recipes but of African musicians, actors, writers and other personalities posing with foods from the African pantry — okra as Freddy Krueger-style claws, chile peppers as earrings — and sharing their favorite African dishes, taste memories and bits of cooking advice. —L.O.

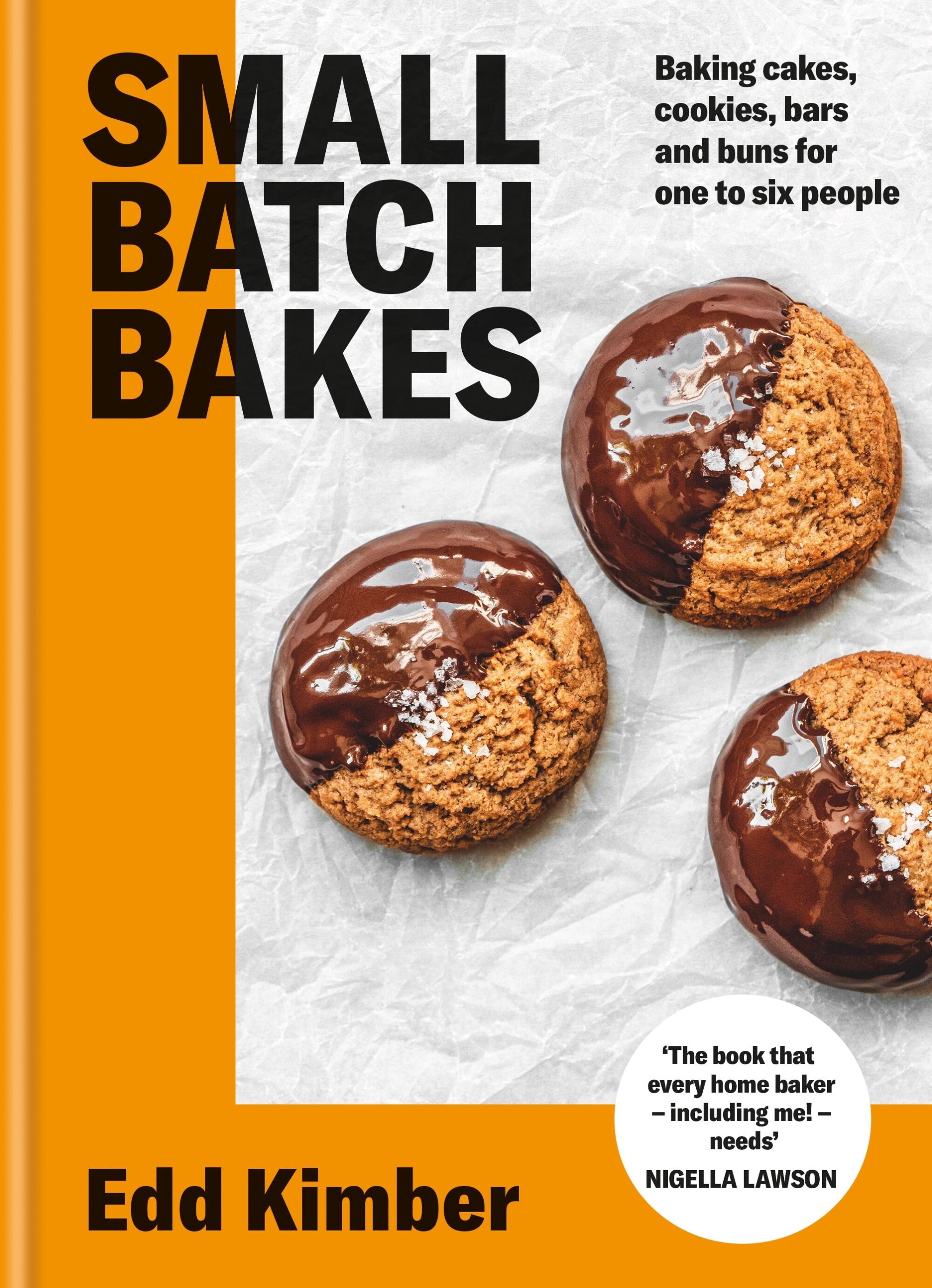

Small Batch Bakes: Baking Cakes, Cookies, Bars and Buns for One to Six People

Edd Kimber (Kyle Books).

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been standing in my kitchen, feeling snacky and wishing I had just one cookie or one piece of something sweet to nibble on. So when my friend Edd Kimber came out with “Small Batch Bakes,” dedicated to baking small amounts of sweet treats, I nearly doubled over with joy. His single chocolate chip cookie was the first thing that snared me, seeing just a few tablespoons of sugar, flour and chocolate morph into a single perfect cookie that you can eat warm from the oven and with no need for sharing. From there, I made his cinnamon bun slices, which give you the perfect amount of cinnamon buns for a weekend alone, and his individual tarte tatins, which makes having a friend over for pizza and a movie way more special by the time you want dessert. I reach for this book most often when I have a handful of chocolate chips or a piece of fruit hanging around that I want to bake into a delicious treat for myself or to give to a friend. —B.M.

Somebody Feed Phil the Book: Untold Stories, Behind-the-Scenes Photos and Favorite Recipes

Phil Rosenthal and Jenn Garbee (Simon Element).

All travel food shows should come with an accompanying cookbook. This is the conclusion I came to after reading Phil Rosenthal’s new cookbook, featuring recipes from every episode of the first four seasons of his Netflix series “Somebody Feed Phil.” His energy and enthusiasm seep through the pages. The best way to experience the book is to watch an episode, salivate over what a wide-eyed Rosenthal is eating, then make it yourself. Or you can make what he ate while he filmed the episode. In Mexico City, Rosenthal tours the farmland where Enrique Olvera grows produce for his restaurants. If you turn to Page 73, you can make the quesadillas Olvera’s son Aldo made for lunch while they were filming.

What some call the best fried chicken in New Orleans (or America) comes to L.A. The great-granddaughter of Willie Mae’s founder opens her Venice restaurant on Lincoln Boulevard.

Some of the best parts of the book, like the series, feature Rosenthal’s late parents, Helen and Max, who frequently appeared in Zoom calls at the end of episodes. And one of the best recipes in the book is Helen’s matzoh ball soup, featured in the New York City episode, when Rosenthal brings Daniel Boulud into his mother’s kitchen to try her soup. It’s similar to the one my grandmother makes, with chicken stock that simmers for hours, dried herbs and precisely two matzoh balls in each bowl.

But this isn’t just a book for fans of the show. Included are recipes from celebrated chefs all over the world, like a greatest hits cookbook with no geographic boundaries. It will make you want to cook, eat and travel the world. —J.H.

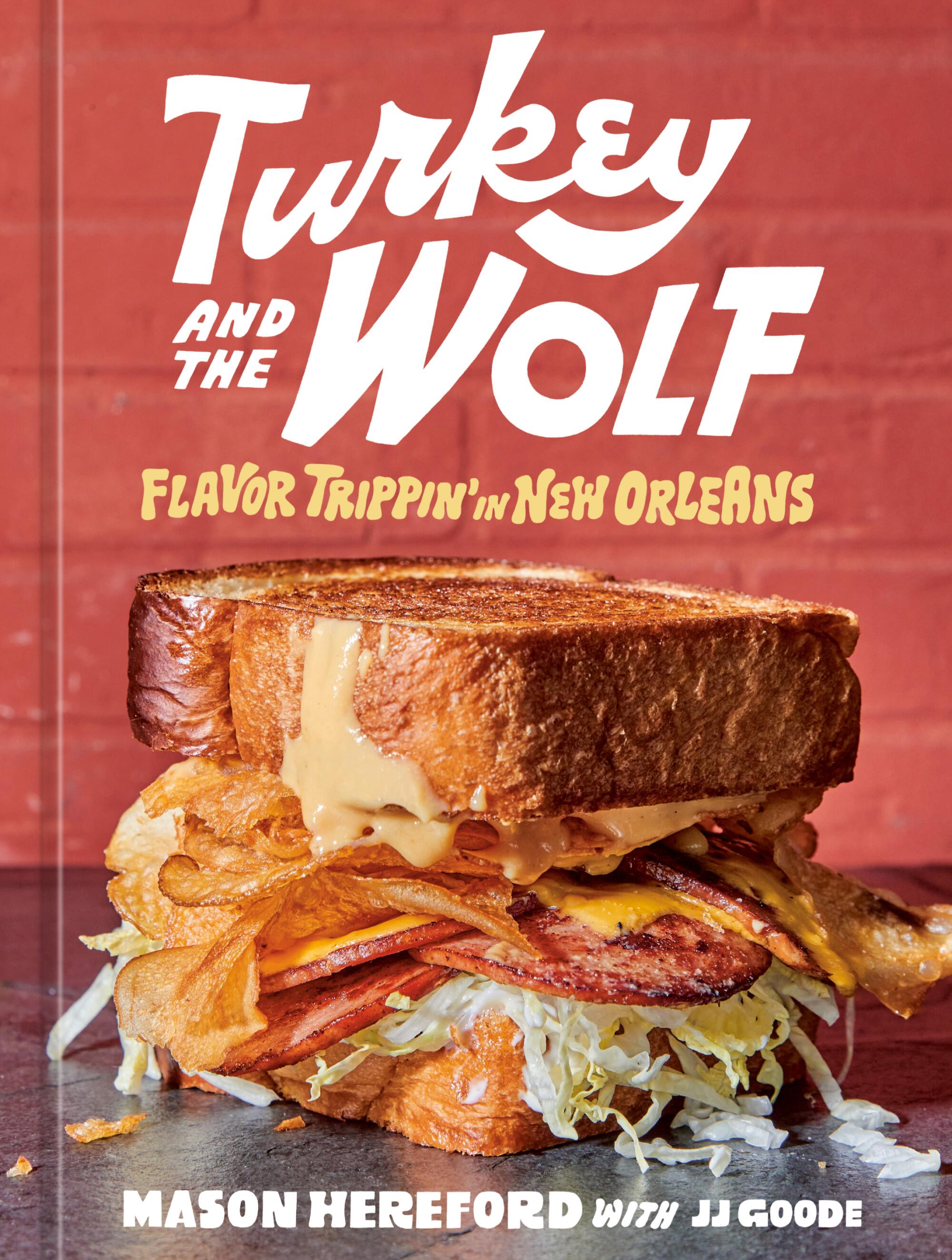

Turkey and the Wolf: Flavor Trippin’ in New Orleans

Mason Hereford with JJ Goode (Ten Speed Press).

This isn’t just a cookbook, it’s a rip-roarin’ good time. I’d expect nothing less from the Deep South’s sandwich destination famed for its irreverent, off-the-walls take on Delta classics in a feverish rotation. With dishes from both Turkey and the Wolf and its follow-up breakfast spot, Molly’s Rise and Shine, chef-founder Mason Hereford’s first cookbook is an ode to his family (biological, kitchen and otherwise) and to the gussied-up “gas station food” of his childhood.

It includes recipes for sunchoke-and-truffle “Dunkaroos,” an entire chapter of dips and spreads titled “When I dip, you dip, we dip,” and his mom’s holiday “Danksgiving Day purée,” with ingredients listed in the form of “Duke’s [mayo] or bust” and “crunk chunks” (Key lime pie cubes), but it isn’t all fun and games and wordplay. Hereford and his kitchen band of raucous-flavor explorers have laid out a few tips we can all use to better our cooking: how to toast bread — and rest it, like a piece of meat — for that harmonious balance of crunch to chewiness; dredging and seasoning techniques for frying everything from chicken to soft-shell crab; and how to quickly assemble a killer tonnato sauce from grocery-store basics.

Every page punches with color and style, every recipe is an invitation to stop taking yourself so seriously. I give it 13 out of 10 potato-chip-topped fried bologna sandwiches. —S.B.

Via Carota: A Celebration of Seasonal Cooking From the Beloved Greenwich Village Restaurant

Jody Williams and Rita Sodi with Anna Kovel (Knopf).

A few years ago, a friend asked what’s my favorite restaurant in New York City, and with little hesitation, I answered. “Oh,” he said, “you mean every food writer’s favorite restaurant?” It’s unoriginal to fall so deeply in love with Via Carota, but it can’t be helped. The trattoria from powerhouse couple Rita Sodi and Jody Williams (of I Sodi and Buvette, respectively) hits every note, its rustic Italian offerings often served simply and so elegantly amid all the reclaimed wood and marble and antique hutches and chairs. Succumbing to the romance of it all is inevitable. We’re woefully a long flight away, but thanks to Williams, Sodi and co-author Anna Kovel we can re-create its signatures at home — yes, including that towering Insalata Verde, a requisite order every visit.

Recipes in “Via Carota” are divided into spring, summer, fall and winter, the restaurant’s hyper-seasonality in clear focus, dividing each section further by produce varietals: asparagus, summer beans, ramps and garlic scapes, squash, peas, citrus, fennel, cucumbers and melons, eggplant, root vegetables — the list goes on — and then there are grilled meats and “basics” of pastas, conservas, broths and the like. (As if any dish from this restaurant feels basic or like a simple building block; simple, clean, deliberate, yes, but basic? Never.) The recipes and chapters are peppered with insights from both chefs, whether they be memories of their time in Italy, tips for shopping for salt cod, trimming artichokes or a general, transportive note on the prevalence of young lamb in the spring. Fortunately the whole book is a bit transportive; we might be a cool 2,800 miles from Via Carota, but at least we can now experience a bit of its magic out here. —S.B.

The Wok: Recipes and Techniques

J. Kenji Lopez-Alt (W.W. Norton).

I read J. Kenji Lopez-Alt’s cookbooks like textbooks. While most cookbooks aim to offer good recipes, Lopez-Alt gets to the science of why something tastes good. And that “why” is the secret to getting a dish right, every time. “The Wok” is a full primer on the wok, with its history, tips for purchasing, notes on materials and design, how to season, clean and maintain it. There’s a pantry list too, for items you’ll frequently need to make dishes in a wok. And I love the sidebars throughout, answering questions such as “what makes Sichuan peppercorns tingle?” Or, “do I really need to toast my spices?” (No.)

My Cantonese grandmother judges all Chinese restaurants by their kung pao chicken, if they serve one. It’s a dish that’s easy to mess up with too much sauce, too little sauce or an unbalanced sauce that’s too spicy or too sweet, and chicken that’s overcooked or rubbery. The sauce should be more of a thin glaze with a punch of heat that doesn’t overwhelm the dish. It came as no surprise that “Chinese American Kung Pao Chicken” is the first recipe in the book.

It’s a recipe that includes many of the tips in the introduction, like the now-let’s-see-what-you-learned test your professor gives you after the first three chapters of a book. At each step in the recipe, I felt confident and prepared. I properly sliced the chicken, heated my wok, infused my oil and thickened my sauce. The result was an excellent kung pao chicken; my grandmother would approve. —J.H.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.