Rice crops threatened by El Niño after grain supplies already disrupted by Ukraine war

- Share via

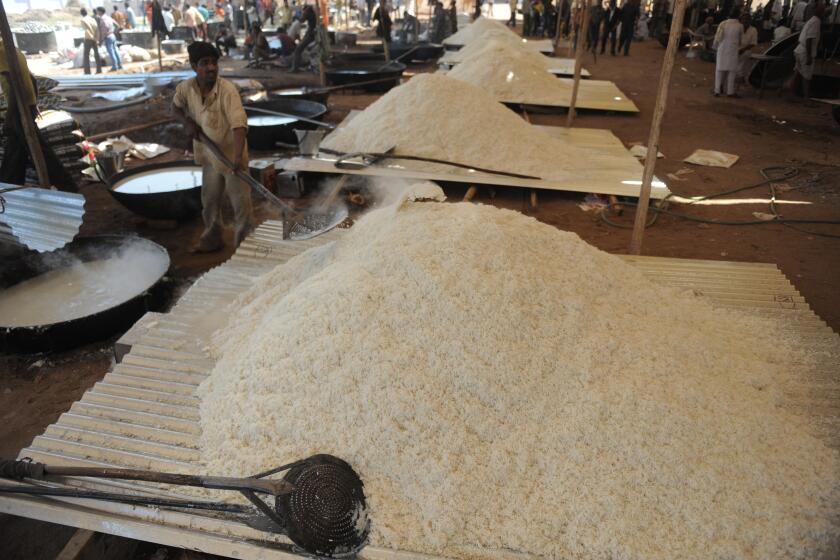

NEW DELHI — Warmer, drier weather because of an earlier-than-usual El Niño is expected to hamper rice production across Asia, hitting global food security in a world still reeling from the effects of the war in Ukraine.

An El Niño is a natural, temporary and occasional warming of part of the Pacific that shifts global weather patterns, and climate change is making such events stronger. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced the present one in June, a month or two earlier than it usually does. This gives the event time to grow. Scientists say there’s a 1-in-4 chance that it will expand to supersize levels.

That’s bad news for rice farmers, particularly in Asia, where 90% of the world’s rice is grown and eaten, because a strong El Niño typically means less rainfall for the thirsty crop.

Past El Niños have resulted in extreme weather as diverse as drought and floods.

There are already “alarm bells,” said Abdullah Mamun, a research analyst at the International Food Policy Research Institute, pointing to rising rice prices because of shortfalls in production. The average price of 5% broken white rice in June in Thailand was about 16% higher than last year’s average.

Global stocks have run low since last year, in part from devastating floods in Pakistan, a major rice exporter. This year’s El Niño may worsen other woes for rice-producing countries, such as reduced availability of fertilizer because of the war and some countries’ export restrictions on rice. Myanmar, Cambodia and Nepal are particularly vulnerable, a recent report by research firm BMI warned.

Growing rice requires huge amounts of water. Did semi-arid California ever have a reliably abundant supply for such a thirsty crop?

“There is uncertainty over the horizon,” Mamun said.

Recently, global average temperatures have hit record highs. Monsoon rains over India were lighter than usual by the end of June, although in the last week they were heavy enough to cause flooding and more than 100 deaths. Indonesia’s president Monday asked his ministers to anticipate a long dry season. And in the Philippines, authorities are carefully managing water to protect vulnerable areas.

Some countries are bracing for food shortages. Indonesia was among the worst hit by India’s decision to restrict rice exports last year after less rain fell than expected and a historic heat wave scorched wheat, raising worries that domestic food prices would surge.

Last month, India said it would send more than 1.1 million tons to Indonesia, Senegal and Gambia to help them meet “their food security needs.”

India’s effort to gain protected status for basmati rice exports in Europe has irked Pakistan, the world’s No. 2 producer.

Fertilizer is another crucial variable. Last year China, a major producer, restricted exports to keep domestic prices in check after fertilizers were among exports affected by sanctions on Russian ally Belarus for human rights violations. Sanctions on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine don’t specifically target fertilizers, but the war has disrupted shipments of the three main chemical fertilizers: potash, phosphorus and nitrogen.

Bangladesh found suppliers in Canada to make up for lost potash shipments from Belarus, but many countries are still scrambling to find new sources.

Farmers like Abu Bakar Siddique, who cultivates three acres in northern Bangladesh, had enough fertilizer to keep his yields steady last year. But less rainfall meant he had to rely more on electric pumps for his winter harvest at a time of power shortages from war-related shortfalls of diesel and coal.

“This increased my costs,” he said.

The Russian government has donated 20,000 tons of fertilizer to Malawi as part of its efforts to attract diplomatic support from various African nations.

Each El Niño is different, but historical trends suggest that scarce rainfall in South and Southeast Asia will parch the soil, causing cascading effects in coming years, said Beau Damen, a natural resources officer with the Food and Agriculture Organization based in Bangkok. Some countries, like Indonesia, may be more vulnerable in the early stages of the phenomenon, he said.

Kusnan, a farmer in Indonesia’s East Java, said rice farmers there have tried to anticipate that by planting earlier so that when the El Niño hits, the rice might be ready for harvest and not needing so much water. Kusnan, who, like many Indonesians, uses only one name, said he hoped high yields last year would help offset any losses this year.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo has stressed the need to manage water well in the coming weeks, warning that various factors, including export limits and fertilizer shortages, could combine with El Niño to “make this a particularly damaging event.”

Baldev Singh, a 52-year-old farmer in northern India’s Punjab state, is already worried. He typically sows rice from late June until mid-July, but then needs the monsoon rains to flood the paddies. Less than one-tenth of the usual rainfall had come by early this month, and then floods battered young crops that had just been planted.

Southern California’s inland areas could see triple-digit temperatures all weekend as a high-pressure system means a brutal heat wave.

With rain scarce, Singh may need to dig wells. Last year, he dug down 200 feet to find water.

“Rice has been our ruin. ... I don’t know what will happen in the future,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.