- Share via

After a year of dominance, El Niño’s wrath has come to end — but its climate-churning counterpart, La Niña, is hot on its heels and could signal a return to dryness for California.

El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, sometimes referred to as ENSO. The climate pattern in the tropical Pacific is the single largest driver of weather conditions worldwide, and has been actively disrupting global temperatures and precipitation patterns since its arrival last summer.

Among other effects, the El Niño event contributed to months of record-high global ocean temperatures, extreme heat stress to coral reefs, drought in the Amazon and Central America, and record-setting atmospheric rivers on the U.S. West Coast, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in its latest ENSO update.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The system is now offering a brief respite as it has moved into a “neutral” pattern — but it won’t stay that way for long.

There is a 65% chance that La Niña will develop between July and September and persist into the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, NOAA said. There is an 85% chance it will be in place between November and January.

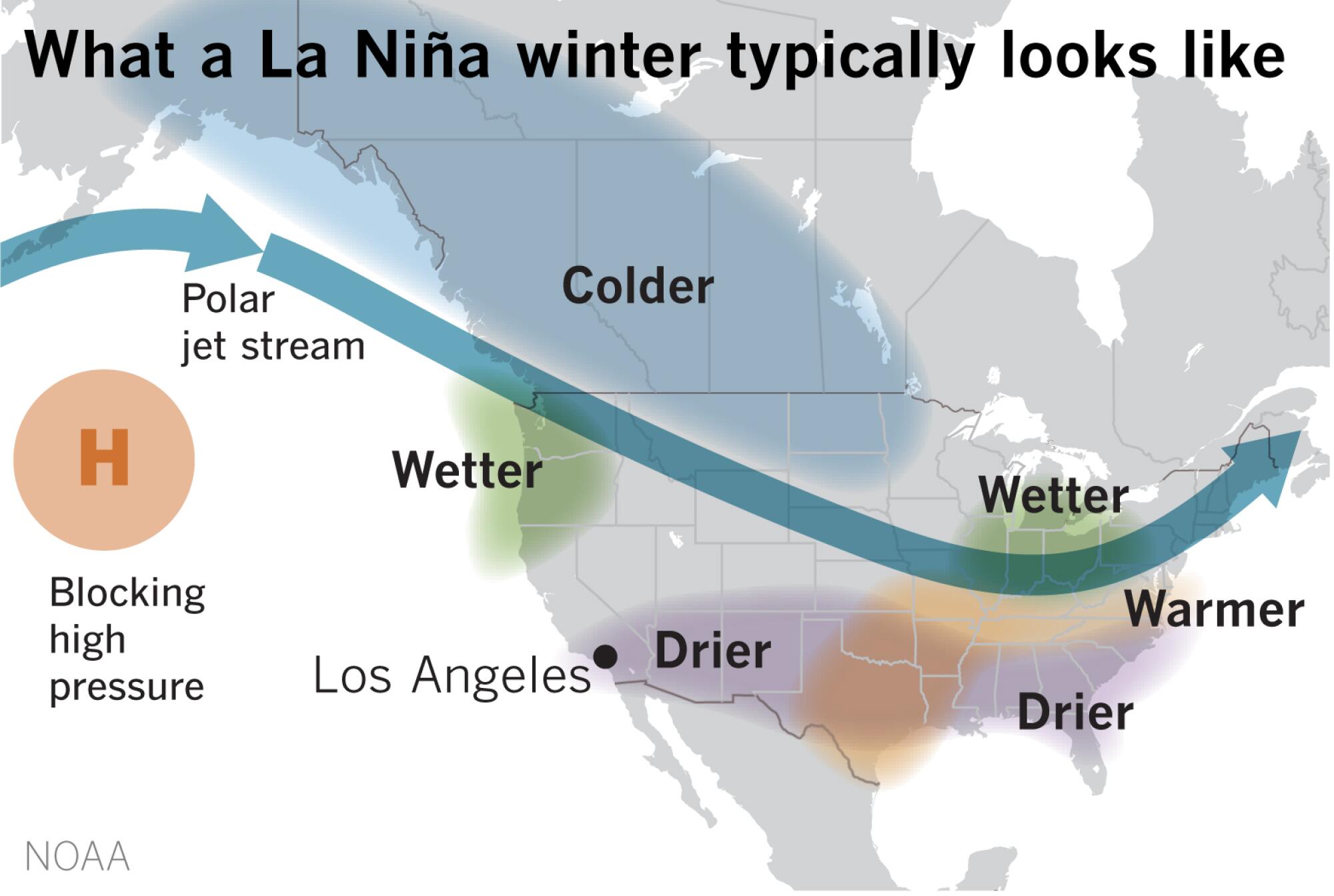

Along the West Coast, and in Southern California in particular, La Niña is often associated with cooler, drier conditions. La Niña was last in place during the state’s three driest years on record — 2020 through 2022 — which saw decimating drought conditions and unprecedented water restrictions for millions of people.

Bill Patzert, a retired climatologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada-Flintridge, noted that Southern California has experienced 25 weak-to-strong La Niña years since 1950, when the modern record began. Nineteen of those years have been drier than normal.

“So for Angelenos, La Niña loads the dice for a drier-than-average winter and is justifiably often called ‘the Diva of Drought,’” he said.

“But it’s not a sure thing,” Patzert added. “La Niña can surprise us. It’s still a crapshoot, but firefighters, water managers and farmers would be wise to be prepared.”

State water managers are indeed preparing — but for either wet or dry conditions later this year, according to Jeanine Jones, interstate resources manager with the California Department of Water Resources.

That’s because La Niña is only one of many factors that can influence California’s weather, and its outcomes are never a guarantee.

Global average temperatures and CO₂ levels continue to soar. May was Earth’s 12th consecutive hottest month on record, officials announced this week.

“Historically, most La Niña years have been dry, but by itself, it’s not a good predictor because other things are going on,” Jones said. “We always like to say that in any given year, because of California’s extreme variability in precipitation, we should prepare for either wet or dry.”

Among those preparations are ongoing discussions about a state climate bond, which would provide more financial assistance to help prepare for both extremes, she said. State officials are also continuing to implement Gov. Gavin Newsom’s strategy — unveiled in 2022 — for a hotter, drier future.

But images of the most recent drought remain fresh in many Californians’ memories, including dead, brown lawns and dangerously low water levels in Lake Oroville and Lake Mead.

Jones noted that the severe water restrictions Southern California experienced during that drought were because of cutbacks from the State Water Project as well as long-term drying conditions on the Colorado River. The good news is that California’s reservoirs are currently at above-average levels following two back-to-back wet winters fueled by El Niño.

“Most water users in California are equipped and accustomed to dealing with a single dry year,” she said. “It’s when conditions persist for multiple dry years in a row that life becomes more difficult.”

New research raises questions about the familiar map’s ability to address long-term drying trends, including persistent dry spells across the American West.

La Niña isn’t only a factor when it comes to precipitation. The pattern could also signal a slight break from the El Niño-driven record-hot global temperatures that have gripped the planet for the last 12 months, NOAA officials said.

However, long-term warming trends driven by climate change could still place 2024 among the hottest years on record, according to Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

“La Niña generally results in cooler global mean temperatures,” L’Heureux said in an email. “However, we are still feeling the effects from the previous El Niño on global mean temperatures, so it’s not altogether clear where this year will rank other than it will likely be in the top 5. Because climate change is increasing temperatures over time, we can expect that La Niña may put a small dent in that upward trend, but it probably won’t be much.”

La Niña comes with other challenges, as well, including ties to the forecasted active Atlantic hurricane season, which is expected to deliver as many as 25 named storms.

L’Heureux said the immediate effects of La Niña will be limited as ENSO has “a very minimal influence on summertime U.S. temperature and precipitation anomalies,” and that its impacts don’t really start to emerge until fall or winter.

The latest winter outlook from NOAA currently points to warmer and drier conditions across the southern half of the U.S., including Southern California. Portions of the Midwest, Montana, Idaho and Washington could see wetter weather.

“The tilt toward increased chances of below-average precipitation and above-average temperatures for the Southwest and California is pretty typical of a La Niña-influenced winter,” L’Heureux said.

Conditions on the West Coast may be calmer than last year, when a rare storm swirled off the coast of Baja California before making landfall in early August.

Its too soon to say how strong this La Niña is likely to be, with a wide range of possible outcomes still in play, forecasters said.

In fact, it is somewhat uncommon for ENSO to flip from El Niño to La Niña within a year, happening only 10 times in the historical record, Rebecca Lindsey of NOAA’s Climate Program Office wrote in the agency’s blog.

Of those instances, four of the six “strong” El Niños evolved into strong La Niñas. But the strongest El Niño of all wound up developing into the weakest La Niña, so “it’s complicated,” Lindsey wrote, noting that the strength of the upcoming event will become clearer as it gets closer.

Patzert, of JPL, also cautioned that La Niña isn’t the only player when it comes to predicting rainfall and temperature — and that global warming is “surely impacting El Niño and La Niña impacts in ways that are not yet fully understood.”

“La Niña’s reach, enhanced by climate change, is global,” he said. “In many parts of the globe, the rainfall and temperature patterns of last year can be reversed from drought to flooding, from wet to wildfires, from economic benefits to punishing disasters. La Niña is a big deal.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.