Here’s what we can do to honor the legacy of L.A.’s P-22, an outdoors inspiration

- Share via

Like many lovers of L.A.’s outdoors, I found myself unexpectedly emotional on Saturday morning after learning that P-22, the legendary mountain lion of Griffith Park, had been peacefully and compassionately euthanized.

The outpouring of support and thoughtful eulogies dedicated to this cat have been, like the cat himself, inspirational. The moment warranted an above-the-fold front-page headline here at The Times and made headlines in other prominent papers around the world. A moving remembrance from the National Wildlife Federation’s Beth Pratt — which is truly a must-read — has been shared on Facebook more than 7,000 times. On the Los Angeles subreddit, users compared P-22’s passing with those of Vin Scully, Kobe Bryant and Jonathan Gold. Someone built a shrine to him in Los Feliz.

For the record:

9:28 a.m. Dec. 27, 2022An earlier version of this newsletter misspelled Steven L. Morris’s first name as Stephen.

I expected L.A.’s outdoorsy set to react this way, but the outpouring of support from Angelenos across the board has been genuinely surprising. It shouldn’t be, though. P-22 was an Angeleno too. He was something the city could rally around, support and most importantly, be proud of.

P-22 made me proud to be an Angeleno. I lost count of how many times I brought him up in conversation with someone who tried to stereotype L.A. as a city of endless pavement, smoggy strip malls and self-absorbed attention-seekers. I loved telling them our Griffith Park is not only five times bigger than New York’s Central Park, but that it also supported an apex predator Angelenos loved and protected.

We should remember that although P-22 lived in Griffith Park for a truly remarkable 11 years, our sprawl also kept him hemmed in there, alone in a range that was only 5% of what an average male mountain lion enjoys. Our insistence on using rodenticide — despite all the horrible evidence of its cascading effects on the food chain — resulted in him getting mange. In his final days, he was struck by a car, a sadly all-too-common fate for living things in L.A. city limits.

There are calls to honor P-22 on the Hollywood Walk of Fame or with a statue in Griffith Park. While a statue would be a great addition, we can much better honor P-22’s memory by working to ensure that future generations of wildlife have an easier time living alongside us than he did.

This year we broke ground on the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, a truly colossal achievement for everyone involved. But one wildlife crossing — even if it’s the world’s largest — isn’t enough. We need more. We need the city’s proposed Wildlife Ordinance District enacted and expanded. We need fewer cars on the road everywhere, but especially in and around our parks and National Recreation Areas. We need to end the numerous exemptions on our statewide anticoagulant rodenticide ban and completely remove them from use. And while we revere P-22 and mourn his loss, we also need to remember that we remain a city surrounded by and integrated with wildlife of all kinds: the red-tailed hawks that soar our skies, the coyotes and bobcats that wander side streets, the bats that circle Dodger Stadium lights, the bottlenose dolphins that frolic off our beaches, the black bears in our foothill backyards and countless others. If you loved and cared for P-22, don’t despair. There is plenty left to fight for and be inspired by, and it is all deserving of our effort.

3 things to do

1. Celebrate the Cats of Festivus. If P-22 news has got you down, why not give some love to the very adoptable, much more house-appropriate felines at Pasadena’s Tail Town Cat Café, which is holding a “Cats of Festivus” event on Dec. 23 at 1:30 p.m.? Yes, this is a thing that is happening. The event will feature six adoptable cats as well as the traditional airing of grievances, attempts to climb the Festivus pole and feats of strength. Again, this is real. Vote on your favorite grievance here. In-person attendees are asked to make a $20 tax-deductible donation. You can also watch the event, which again, is real, live on Instagram.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

2. Walk Holiday Road. I found out long ago it’s a long way down the Holiday Road (oh-oh-oh-oh-oh). Enjoy the annual holiday light festival at King Gillette Ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains from now through Dec. 30. If you haven’t been before, it’s a 2/3-mile walking path decked out with thousands of lights, candy canes, festive foods and drinks (including some winter warmers for the 21-plus crowd). Tickets to the Holiday Road (oh-oh-oh-oh-oh) are timed, and start at $24.99. It truly is a West Coast kick (oh-oh-oh-oh-oh).

3. Hike the beach. Get to know the coast of San Pedro with the Palos Verdes Group of the Sierra Club’s Angeles Chapter on a 6.4-mile hike from the Handmade Marketplace to Point Fermin Park. The hike will include some city streets but aims to hug the beach as much as possible. Meet up at 8 a.m. on Dec. 24 (get there early to snag street parking!) and bring a snack and water. Minors permitted if accompanied by a parent or guardian. Free. Get more info here.

The must-read

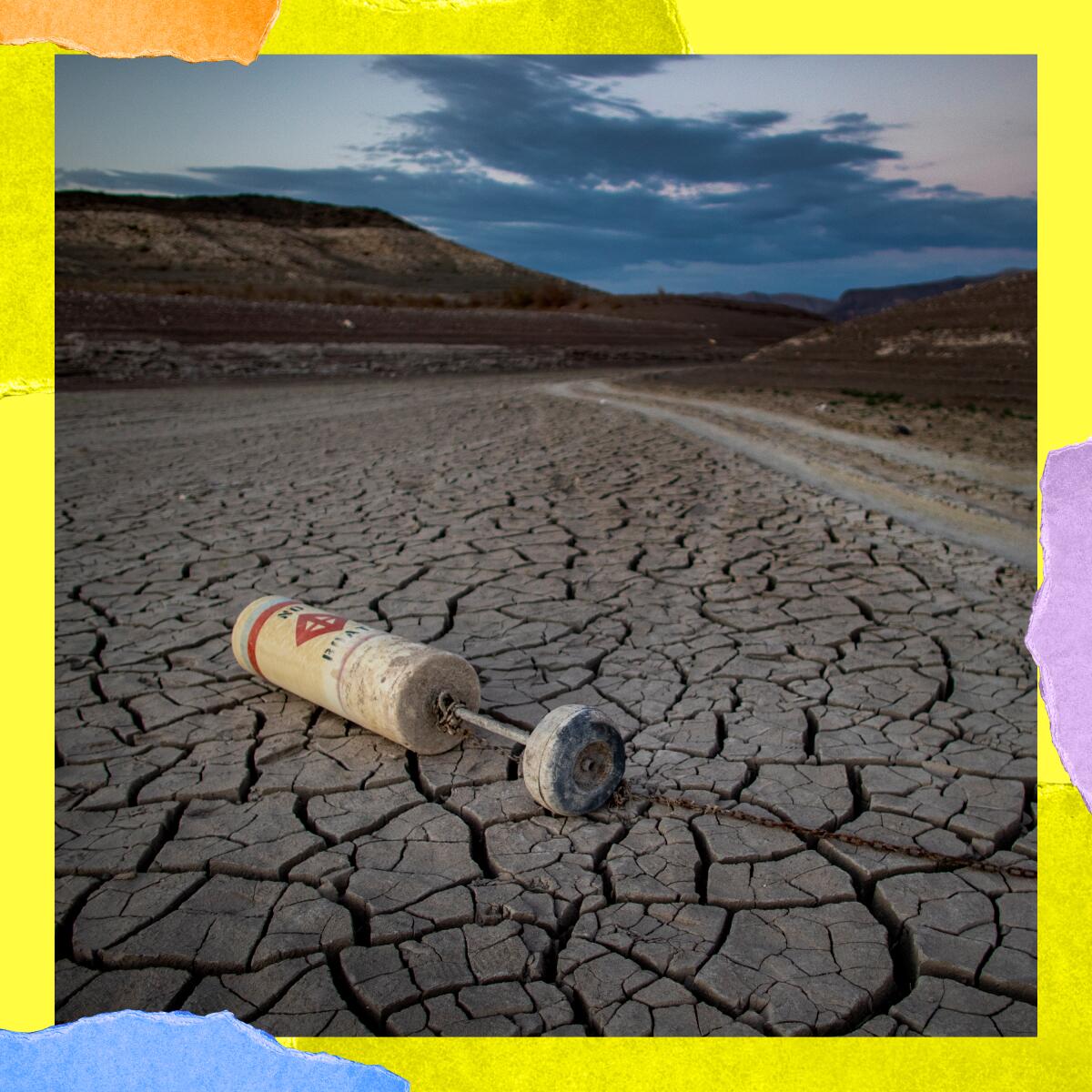

L.A. gets a lot of its water from other places, and one of those places — the Colorado River — is in serious trouble. Federal officials have said there is a serious risk that water levels in Lake Mead could reach “dead pool” levels in 2025, meaning the water would not be high enough to flow downstream past Hoover Dam. Lake Powell is so low that Glen Canyon Dam is in danger of not being able to generate electricity. A big source of this problem is the extremely complex water-sharing agreement for the Colorado River, which just happens to have been designed during a time when water flow was abnormally high. Read the full story at the L.A. Times, and maybe start watching your water use.

Check out “The Times” podcast for essential news and more.

These days, waking up to current events can be, well, daunting. If you’re seeking a more balanced news diet, “The Times” podcast is for you. Gustavo Arellano, along with a diverse set of reporters from the award-winning L.A. Times newsroom, delivers the most interesting stories from the Los Angeles Times every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Wild thing

A recent longform article in the Atlantic says humans are altering the ecosystems of the planet to make them all the same everywhere, something wildlife biologists call “biological strip malls.” Case in point: You’re probably aware of efforts to save “the bees,” and maybe you’ve even planted some flowers yourself to help. But were they native wildflowers? And were you attracting European honeybees? Then you might have been accidentally aiding this strip mall expansion. No matter where you live, the plants around you have co-evolved with specific pollinators, and those European honeybees don’t always do the job. Enter a newfound love and respect for native bees, which are far more varied and interesting than the cartoon bees you’re probably picturing in your mind. The L.A. Times has a fascinating and fun profile of artist Krystle Hickman, who’s on a mission to photograph California’s 1,600 species of native bees.

Five questions with ... QT Luong

QT Luong was born in Paris and trained as a scientist, but was lured by the cliffs of Yosemite National Park and moved to the Bay Area in 1993, which sparked a love of the National Park System. He set out to photograph all the park units on large-format film, which had never been done before. This became the bestselling, award-winning book “Treasured Lands.” His work has been seen in traveling exhibitions and even on U.S. postage.

In 2022, Luong received the Ansel Adams Award for Photography from the Sierra Club. I talked with him about his most recent book, “Our National Monuments,” which documents the nation’s lesser-known outdoor destinations. Learn more about his work at his website.

Answers have been edited for length.

How did you get into photography?

My world as a city kid changed when college friends took me up the high peaks of the Alps. I took up photography to bring the beauty of mountaintops to friends and family who could not get there.

Most people are familiar with national parks, but not with national monuments. Why do you think that is?

The idea of national parks is easy to grasp, but the very term “national monument” is confusing. People sometimes don’t realize they offer great scenery and recreational opportunities. Also, since 1996, most of the landscape-scale national monuments are administered by the Bureau of Land Management, which is a much lower-profile agency than the National Park Service.

What inspired you to create this book in the first place?

When, after a “review” of 27 areas in 2017, the former president eviscerated the protections of two of the largest and most beautiful national monuments [Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante; President Biden restored protections, though the battle continues] to pave the way for extractive industries, I resolved to take action the only way I knew, by hiking and photographing the 22 national monuments on land endangered by the review.

Those national monuments include vast lands rivaling the national parks in beauty, diversity and historical heritage. Even though I had been photographing America’s public lands for a quarter-century, many of them were previously unknown to me. I reasoned that those areas were vulnerable because the general public did not know about them.

What was the most surprising place you visited?

When I traveled to Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, I was expecting to see a landscape with prairies mixed with badlands and bluffs typical of the great plains, but while floating the river, I was surrounded by tall cliffs and other spectacular rock formations. Forests of pinnacles and slot canyons where water has carved sandstone into fantastic curves and shapes were reminiscent of the Southwest. Although the area is surrounded by agricultural lands, during a four-day paddling trip, I was also surprised to see that the place has remained so wild, with almost no signs of modern development along the river corridor.

Give us a short pitch for your favorite national monument in California.

At first, Mojave Trails National Monument appears to be a vast, barren and unremarkable expense of desert. A closer examination reveals numerous geological wonders: rugged mountain ranges, isolated sand dunes, a perfectly symmetrical cinder cone with a miniature playa inside and a spectacular lava flow home to the largest concentration of caves in Southern California.

Only a few miles removed from Interstate 15, Afton Canyon remains hidden and unknown to the millions that speed across the desert. Still, the canyon is large and deep enough that it has been nicknamed the “Grand Canyon of the Mojave.” It is one of the few places where the Mojave River reliably runs on the surface, a rare sight in the desert, supporting a lush riparian area with bighorn sheep and various kinds of birds. Sitting next to Interstate 40, Bigelow Cholla Garden Wilderness protects stands of the fluffy cactus more extensive and denser than Joshua Tree National Park’s famed Cholla Cactus Garden, yet I had the entire place to myself. Despite a dozen visits to Death Valley National Park, I could never find the Mesquite Sand Dunes devoid of numerous footprints from other visitors, but at the Cadiz Dunes, I saw only animal tracks.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.