- Share via

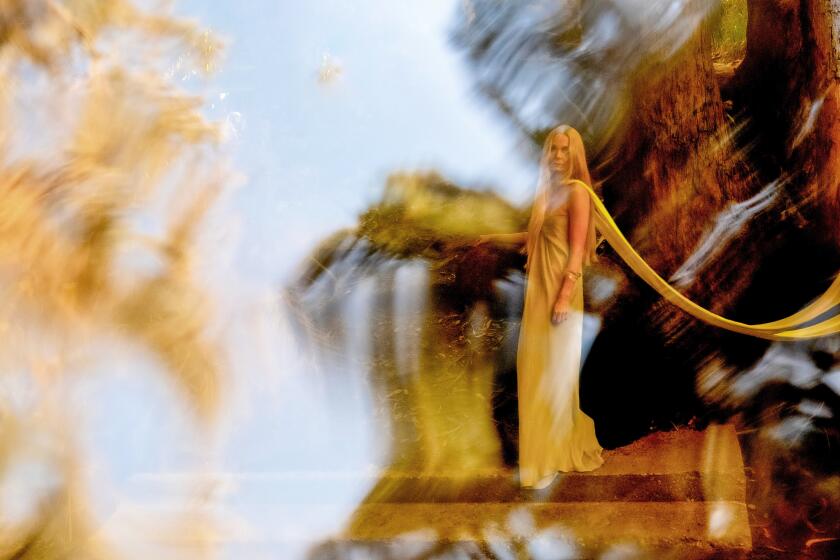

This story is part of Image’s April issue, “Reverie” — an invitation to lean into the spaces of dreams and fantasy. Enjoy the journey.

The first Visitation occurs in a dream on the wings of an aircraft transporting me and my mother to San Antonio, because my sister has died. My sister materializes through golden-hued cumulus clouds, beckons with her hand for me to come to her, and so I do. In my palms, she drops an orb of pure golden light before retreating back into cloud.

Visitations, in addition to meaning a gathering of friends and family for the recently deceased, can also be defined as a visit from the deceased. In my Dreaming Life, my sister returns, randomly yet always intensely, to travel here to me within my perceptible life, to tell me things. It is not always so clear what it is that she has traveled so far to tell me.

Instead of holding a visitation, my family chooses to offer two funeral services. A whole grocery store cannot be shut down, so we opt to hold the service over two nights, to allow my deceased sister’s coworkers to come by between their shifts.

Every person — customers, old school friends, neighbors, children of exes — holds on to me to say how my sister had been their angel and inspiration and life’s guiding light. My sister, who died at age 48 of breast cancer, had become an angel through the workings of Death, but she had — as reaffirmed again and again through the tears and sorrows of the receiving line — also been an angel in her Waking Life.

Visitations occur because those who mourn occupy an unreal space; loss transcends reality or else collapses that once-stable sense of self, space and time.

Visitations occur because those who mourn occupy an unreal space; loss transcends reality or else collapses that once-stable sense of self, space and time. As any of us who have lost know, such deep losses fracture the self. Loss upends our notions of space: The space is now dominated by an insurmountable absence. This absence distorts time or those edges of days or weeks or months that were once so clearly demarcated.

In mourning and grief, it is this very haze of the fracturing of self, space and time that can find, in the practice of Visitation, some temporary bearings within a world upended. To see the familiar faces, to hear the old story, to think about the old song — such remembrances tether us, however frayed and fragile the gossamer of grief, to a world transformed. The world is now distorted: it is a world where someone’s gone missing.

Watching your dream play out before your eyes in waking life is like inhabiting an alternate reality: hair-raising, confronting, wrecking.

In the world now absent my sister, I cling to each and every Visitation from her as she comes in dreams. I have always had a peculiar interest in the Dreaming Life, and after my sister died, I found that if I wanted to continue some form of communication with her, I would have to be the astronomer and detailed data collector in the observatory of sleep. Only I could keep the lookout; only I could transcribe the fates.

So I began to entangle my Waking Life within the Dreaming Life.

Everyone suddenly, it seems, wants to lucid dream. I say: First dream, but dream actively. Here are some practices I take to ensure an engagement in my Dream Life:

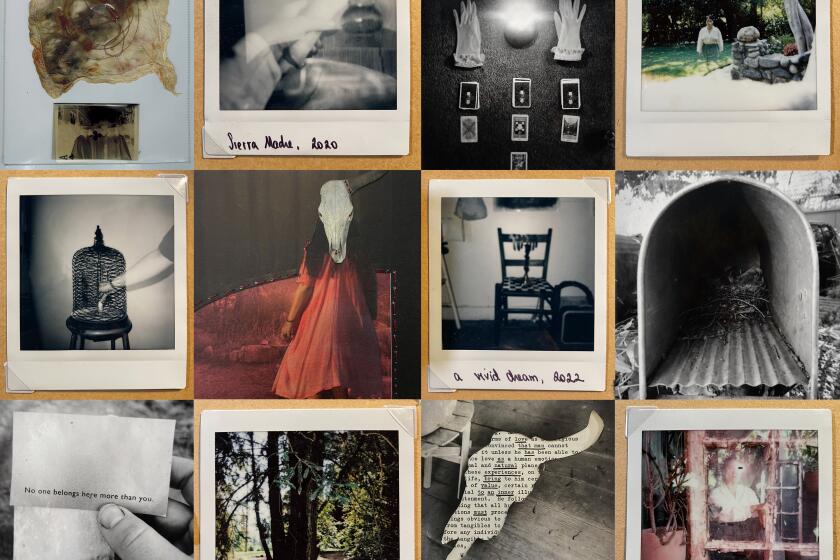

- Keep a notebook bedside. Reach for this notebook first thing upon waking, whatever the hour. Even if you can’t recall any dreams, this practice, which can be difficult to establish, will develop into a habit. If you cannot recall the dream fully formed, then record dreamlets — the fragments of dreams.

- Drink water. The body, of course, is optimal when hydrated, but falling asleep with a full bladder will help you to wake in the middle of the night with a glimmer of a dream. Be sure to discipline yourself to write your dreamlets down before you go to the bathroom and forget. Keep a notebook by the toilet to help you remember.

- Rest your mind before sleep. Tell yourself that you are going to dream and that you will remember your dreams and that you will write them down. It’s OK if you’re stressing or thinking troubled thoughts before bed. Think what you will, but always firmly believe that you will dream. I recommend reading before bed, as it is an activity that stimulates the mind, imagination, openness to surprise, close attention and interpretation: These are the stuffs of reading your own dreams.

- Sleep in. We have more opportunities to dream when we are able to sleep in. Give yourself the gift of this at least once a week.

- Try mugwort in your bedtime tea. After a few weeks of active dreaming, try mugwort tea on the nights when you can sleep and dream more freely. Mugwort is an herb that is easily foraged and induces more vivid dreams. A teaspoon will suffice.

- Ask yourself what is troubling you. Can you reframe this worry through what your dreams have been showing you?

By paying attention to your dreams and collecting your dreamlets, you will begin to see a way out. You can face the situation, in however a veiled or coded way, in your dreams. You can practice your way out or through or in.

L.A.-based artist Amanda Maciel Antunes opens up another realm to talk to the famed erotics writer and diarist — 45 years after her death.

In a dream, I was once an unexpected visitor. I came upon a corridor, white and filled with light, through which my sister glided. I ran after her, but I was stopped by an attendant, in white, who told me that I couldn’t go through the doors but that my sister was there, on the other side, making it beautiful for me.

And so who’s to say that in this life, we are not merely visiting? If the dreams of unborn babes are the dreams of practicing at living, for what then is this Waking Life preparing us?

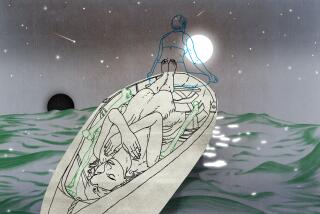

In one dream, my sister wants to go to Brazil. We’re on a highway in San Antonio. We’re going fast around all the cloverleafs and overpasses. We take curves dangerously fast. I tell her that I’m happy to go with her, but does she know the way? Yes, she replies. She says she goes all the time. She knows the way. In the dream, we never get there, but we’re so happy to be free, to just do it, to go wherever, whenever with a sister.

In dreaming, it’s not so easy as paying attention to merely one dream. One dream taken out of your map of dreaming is merely a piece, a clue, a hint toward a totality. One dream is one spot of paint viewed up close on an otherwise vast masterpiece — you won’t know what it is you’re seeing until you’ve amassed enough, connected the dots, done the good work of a detective.

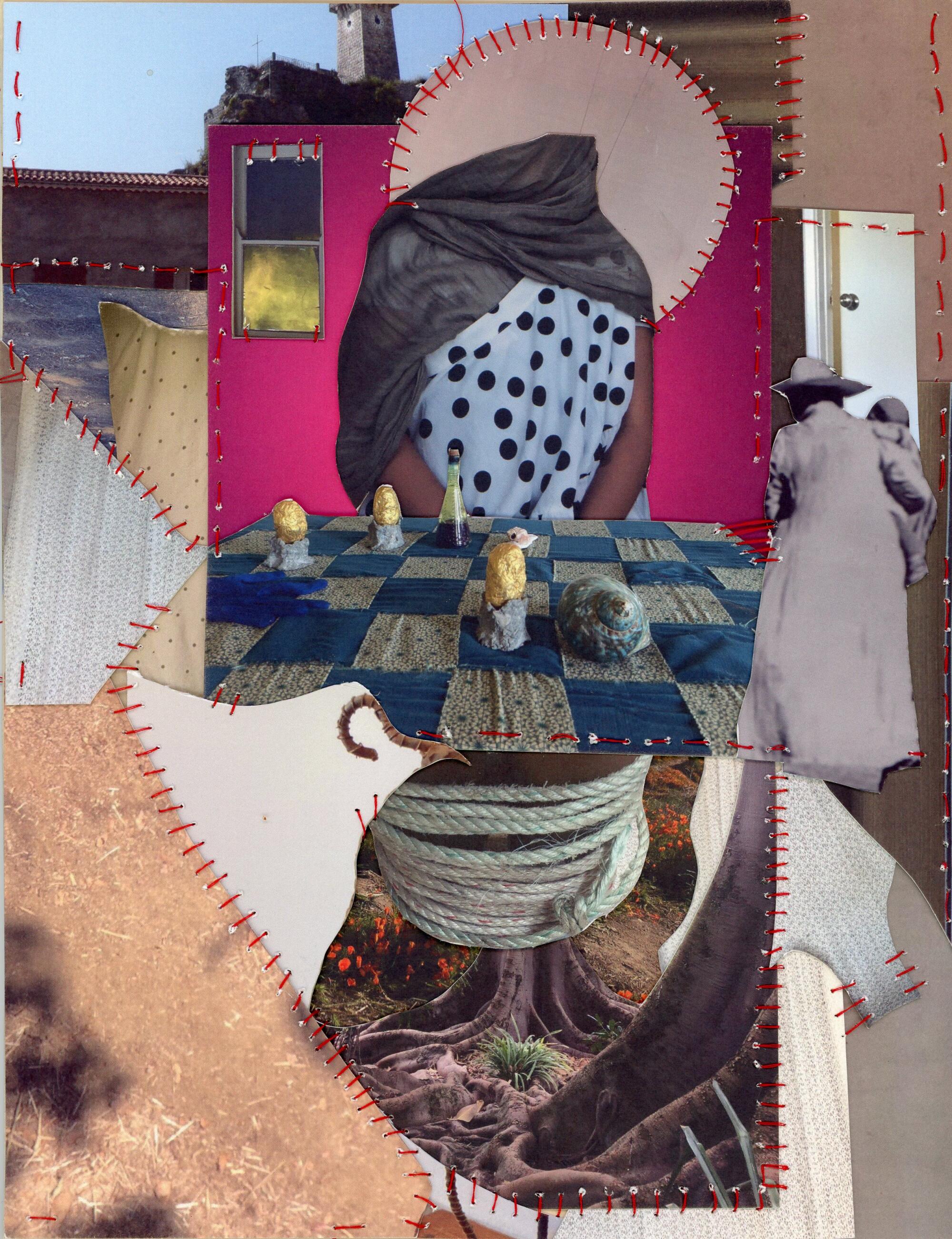

I am a writer who gains through fragments, rarely composing a full essay in one go. I prefer instead to accumulate the bits and pieces, stitch them up, allow happenstance and discovery to arrange the pieces, determine the binding. I like to begin in chaos and have that chaos propel its own focus or refractured brilliance.

My Dreaming Life is no different: I see dreams as fragments of a greater masterpiece. So I jot down my dreams.

My Dreaming Life is no different: I see dreams as fragments of a greater masterpiece. So I jot down my dreams. These dreamlets, these glimmers of a seemingly real and lived experience, eventually pull toward their narratives, eventually show me my struggles and push me on toward a way out in such a way that I can solve the problem in the Dream World while simultaneously tackling a very real-world problem. The two are not inseparable.

I collect the glimmers and connect the dots. My sleuth side sees dreams as not a mere escape from the logic or hardships or realities of the day but rather a world in the making. The dreams enable me to prepare for the next life as it navigates me, night after night, from one realm to the next and back again.

My sister and I entered the scary exhibit at a wax museum on one of the outings we last took together. She was afraid of what might appear. I held her hand and led the way. I knew it would be one of the last times I would hold her hand. My sister, who had always gone first in my fear of dark hallways, was now being led by my hand.

Except, in Waking Life, that is in reality, my sister is the one who goes first into the fear of the dark, into the dream of Death, of which I have always held a tight fear.

If I am to see what there is to see in the ongoing series of Visitation dreams from my deceased sister, then I would have to conclude that she is truly there, on the other side, making it beautiful for me.

Jenny Boully is a Guggenheim Fellow whose books, including “Betwixt-and-Between,” employ dreams alongside real-life entanglements. She has two books forthcoming from Graywolf Press. In addition to teaching at Bennington College, she offers private dream writing guidance.