- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 12, “Commitment (The Woo Woo Issue),” where we explore why Los Angeles is the land of true believers. Read the whole issue here.)

For everything that has been documented about Anaïs Nin, the French American writer, it is odd that she is so misunderstood. Her legacy has been reduced to her erotica and sexually explicit writing, her biography flattened to her famous lovers (Henry Miller) and bigamy, as she kept one husband in New York (filmmaker Hugh Parker Guiler) and another in Los Angeles (forest ranger Rupert Pole). Many know about her time in L.A. — where she lived, part-time, during her last 20-some years — through her Silver Lake house designed by Eric Lloyd Wright, grandson of Frank Lloyd Wright.

But even that obscures the other chapters that more fully bring her existence into view. Nin’s life reflected her converging identities: immigrant, mystic, writer deeply invested in the female psyche. And there was another L.A. house, of course, the one she lived in before Silver Lake in the 1950s, located at the foot of Sierra Madre Canyon. This abode is where her spirit lives, as Brazilian artist Amanda Maciel Antunes has come to know. Over the past decade, Maciel Antunes has been having conversations with Nin — the “invisible woman.”

Maciel Antunes traces this cosmic relationship to when she first immigrated from Brazil to the United States at age 20. Speaking little English, she sought affordable, used books to learn the language. The first book she chose was Nin’s “Diary Vol. IV.” When Maciel Antunes was working at an antique shop in Boston, a patron donated his entire collection of Nin’s books. In Los Angeles, the first gallery to offer Maciel Antunes a solo show was named Luna Anaïs, partly after the writer. But Maciel Antunes’ relationship with Nin crystallized on New Year’s Day 2019, when she went looking for a new home with her husband in Sierra Madre Canyon. They saw a sign for rent with a handwritten number; the landlord picked up and showed them a small apartment. Noticing Maciel Antunes’ interest in the cluster of cottages on the property, the landlord offered to show his own place, as he was moving out.

“I immediately fell in love with the house,” Maciel Antunes wrote in her diary after the fact. “I remember thinking quietly ‘This is perfect’ as we walked through the many doors inside the circular home.”

Soon, they moved in. Curious about the origins of the house, she Googled the address and came across an article about Nin. “I froze and I felt sick,” Maciel Antunes wrote. Nin’s exact address in Sierra Madre, “was also my brand-new address.” Her encounters with Nin no longer felt like mere coincidences. The shift went from “‘I’m a fan” to “I’m in dialogue with this woman.” Nin became “a significant mentor.”

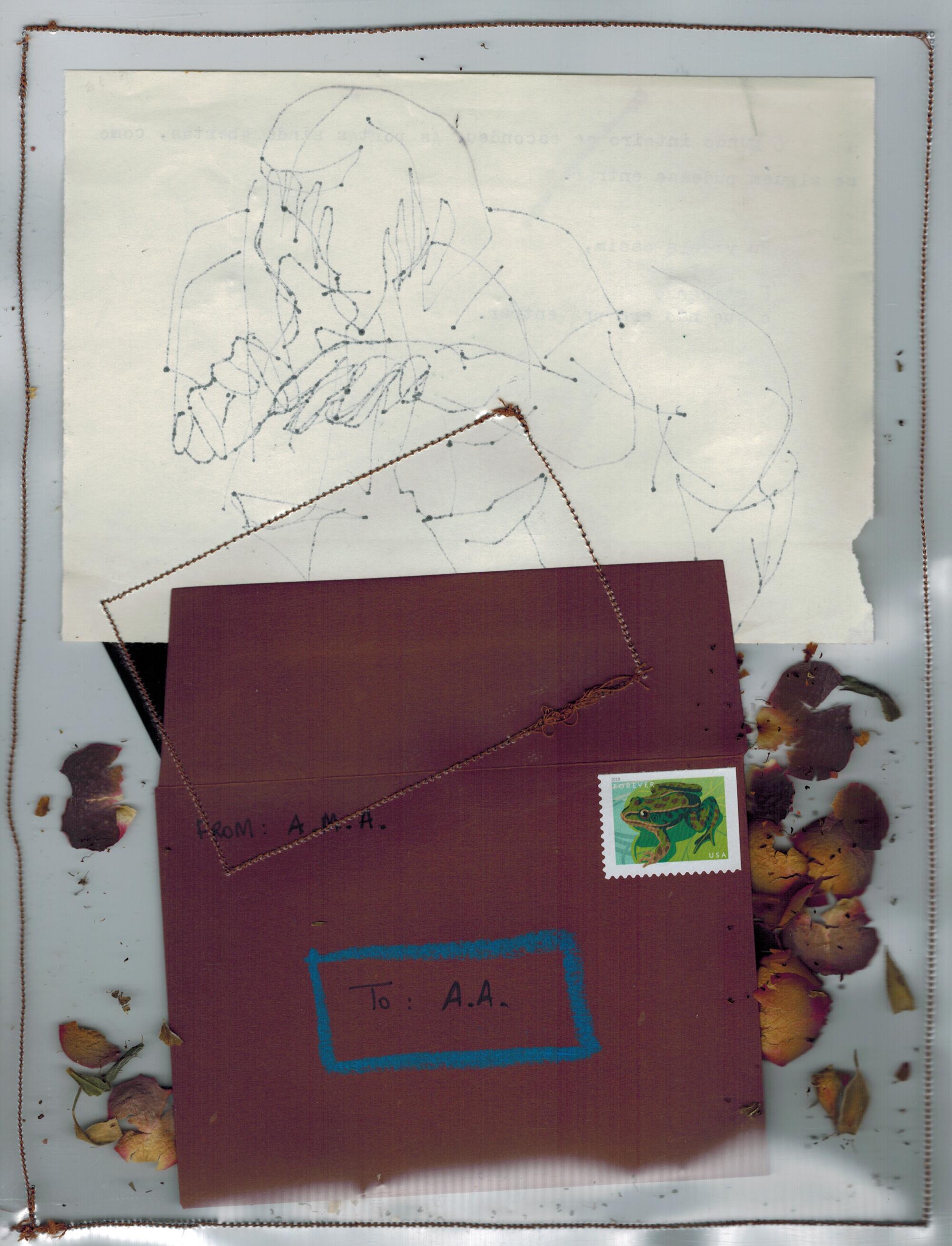

Today, Maciel Antunes speaks with Nin through various means: through her art, through letters. Sometimes, while reading Nin, it feels as if the author’s words are responding to Maciel Antunes’ thoughts, almost reading her mind. Sometimes, she will light a candle in the house and share her troubles with Nin.

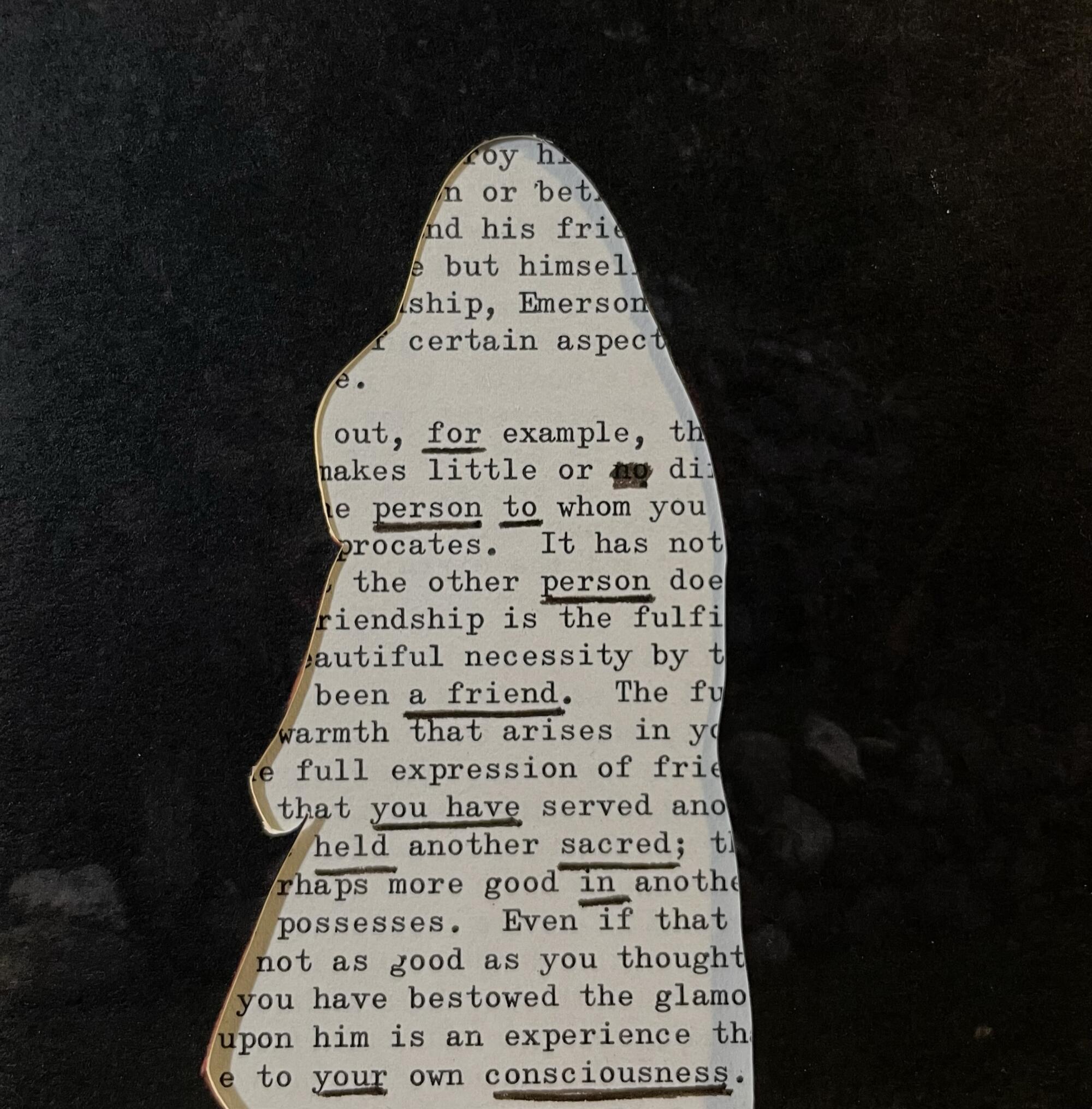

What follows is a conversation between the two women, cobbled together from stories Maciel Antunes has shared and passages she’s underlined by Nin. “This is about seeing into other realms,” she says, “beyond the reality I can see.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Amanda Maciel Antunes: Moving to a new country, being a woman trying to live as an artist — I didn’t know all those things were possible for me until I read you. It was like you knew you were putting it down for someone else to find it in the future.

Anaïs Nin: You have not yet discovered that you have a lot to give, and that the more you give the more riches you will find in yourself.

It is also true that creation comes from an overflow, so you have to learn to intake, to imbibe, to nourish yourself and not be afraid of fullness. … Permit yourself to flow and overflow, allow for the rise in temperature, all the expansions and intensifications.

AMA: Your diary hit me like a bullet. It gave me the courage to stay in a foreign country while I tried to find my identity outside of my family and cultural background.

AN: The diaries served multiple purposes. Because when you are uprooted like that you begin to realize that the only place in which you can really plant permanent roots is in your own self.

AMA: I kept receiving your work through serendipitous relationships. I suppose I felt it was my task to continue reading you. You saved my life on multiple occasions.

AN: One always has an impression of being a solitary human being and unique — I found that my diary wasn’t belonging to me, that it was other women’s diaries too.

AMA: When I moved to Sierra Madre, I brought supplies to paint the interior of the cottage, as an act of commitment to the space. Because maybe if I painted it myself, it would mean that I had marked the territory and set the place apart from all the other homes where I had never felt at home.

AN: I failed to bleach the dark brown walls of the house lighter.

It was a Forest Service house and Rupert was a ranger. In the summer he fought fires, he patrolled with a green car, he rescued people who got lost in the canyon. In the winter he worked on flood control and on Sundays he patrolled. He granted fire permits. He lectured on conservation. He examined fire hazards.

We drove toward the mountains and left of the Santa Anita racetrack. We drove toward very old sycamore trees and a navy-blue sign reading “Sierra Madre.” Sierra Madre was a grand mountain behind our house. In the car, we climbed.

AMA: In 2020, there was a large fire coming toward Sierra Madre. I knew you had also lived through a fire in the house. And I wondered which fire it was. Because at that point I was following a thread — I was open to the mystery of it. The 2020 Bobcat fire was on the east side of the San Gabriel Mountains behind our house. The path was exactly the same one you described coming toward the house from that side of the mountain 50 years earlier.

Fire, as you’ve written, is kind of a cosmic thing. It’s a symbolic thing. Knowing this helped me go through it; I felt like everything was going to be OK. I was so calm.

AN: The fire was like a ring around Sierra Madre; every mountain was burning. The fire grew immense, angry, and rushing at a speed I could not believe. The dragon tongues of flames devouring, the flames leaping, the roar of destruction and dissolution, the eyes of the panicked animals, caught between fire and human beings, between two forms of death.

What did I wish to save? I thought only of the diaries.

It is easy to love nature in its peaceful and consoling moments, but one must love it in its furies too, in its despairs and wildness, especially when the damage is caused by us.

AMA: It can’t just be a coincidence that I’ve been following this track. Why not be open to the fact that your spirit is in the house? Sometimes I will be in the bathtub talking and I imagine you sitting next to me listening. Sometimes I imagine you watching my baby while I go to the bathroom.

Many months ago, I sent you a letter and placed it in the mailbox. I asked you, “What is blasphemy?” I was getting my citizenship in the United States. I was becoming a citizen when Trump was in charge. I felt that I was committing blasphemy. I was really split.

AN: Since I persisted at accusing America, I wanted to look at what I hated. … The paradox was that the one who was truly to blame for my having come to America was my father. Instead of being angry at him, I got angry at America. I identified with the real cause of all my troubles.

Rebellion was an important part of my personality. I was angry. No matter what America was, even if it was all I said it was, there was still no reason for hating it.

AMA: A few days after I sent you the letter, a bird’s nest appeared in the mailbox. I remembered that you had this picture of you wearing a bird cage.

AN: I was once invited to a masquerade party in which we had to come dressed as our “madness.” I wore skin-colored net stockings up to my waist — leopard-fur earrings glued to the tip of my naked breasts — a leopard belt on my waist, and my head inside of a bird cage.

AMA: The bird cage was a metaphor for your madness. You were living in Sierra Madre at the time.

AN: The truth is I hated Sierra Madre, the people, the lives they led. I hated the life we led. It was mediocre and filthy and dull.

I wondered: How can I reach the life I love with Rupert, and be free of chores, no longer a servant?

It was the same pattern in Sierra Madre, the same design and same neurosis.

AMA: In the middle of the pandemic, I felt like I was really going mad in the house. I was taking long daily walks in the canyon and objects would appear on the side of the road. They were very specific objects I was thinking about, reading about, in this relationship with you. One day, I found a bird cage.

I accepted the objects as gifts from you. There was a bullhead with one horn. One horn, to me, is symbolic of the split half — like the trapeze, maybe one side weighs more than the other. You spoke a lot about the trapeze life, the divide, the split self.

AN: I could have been happy with Rupert in that core of fantasy and sensual fusion that we entered at night, but I knew that only one life would ultimately destroy me. I had to make a decision that I eluded after years of lies and games, of living on a trapeze, of fear of falling in between, or of one love getting hurt; I had been incapable. I went for help when the divided lives became maddening. I craved peace, a choice, a simplification. Which one? Whatever I chose seemed to demand a sacrifice I couldn’t make.

AMA: My trajectory as an immigrant felt like that. I was always in search of a place that I could call home. Because it was never necessarily a geographic place. It’s not about being in Brazil or being in the United States. It’s more about what consists of home — friendships, landscapes or maybe a tree. This house had all the elements that felt like home to me. I felt seen.

AN: No one belongs here more than you.

AMA: Finding this place was like finding oneself in the form of a ghost. Am I writing about you, for you, from you? Or about me, for me, from me?

AN: Did I try to say indirectly, by my art: This is who I am?

AMA: You are my spirit guide. You kept me company when I needed it the most. In conversation with you, I answer some of my own questions.

More stories from Image