- Share via

In October, Lauren and Peter Lemos locked the doors of their Chinatown sandwich shop for what they thought would be the last time. In late March they flipped Wax Paper’s lights back on — not due to newfound success or a windfall but because they couldn’t afford to shut down.

“After closing Chinatown we realized we still have our lease, we still have our [federal] loans from the SBA, from COVID, the bills are still coming in,” Lauren Lemos said. “We can’t even afford to close. We can’t afford to be open, we can’t afford to be closed.”

Wax Paper’s husband-and-wife team are hardly the only ones facing economic crises. Interviews with more than two dozen chefs, restaurateurs, policymakers and advocacy groups revealed pointed concern over the state of the service industry, and questions of longevity — especially in light of 2023, a particularly difficult year for restaurants in Los Angeles.

The year was marred by entertainment industry strikes that affected the service industry throughout the region; pandemic-era loan and rent repayments coming due; and inflation of ingredient prices and services such as kitchen repair. L.A. restaurant closures included those from some of the country’s most celebrated chefs. Nancy Silverton shuttered the Barish; Walter and Margarita Manzke closed Petty Cash Taqueria and Sari Sari Store; Daniel Rose shut Café Basque; and Jean-Georges Vongerichten closed his eponymous restaurant in Beverly Hills.

The Lemoses’ second location of Wax Paper, where heaped sandwiches named for NPR hosts and a small diner-style counter always saw a colorful lunchtime crowd, was hemorrhaging money.

On a good day, post-pandemic, they would break $2,000 in sales — though Lauren Lemos estimates that they should have been making between $4,000 and $8,000 for their business model to make sense. In 2023, some days they didn’t break $1,000 in sales — which wouldn’t even cover the cost of the shop’s labor.

The duo considered moving money from one restaurant to another, but with their Frogtown restaurant, Lingua Franca, also facing financial difficulty, they ultimately decided that they would only be bailing water without plugging the hole.

“Costs are higher than ever, risks are higher than ever,” said Lauren Lemos. “I always want to have some kind of optimistic outcome for the future, but I do really worry, ‘Is it going to be sustainable?’ I’m not sure we’ll have mom-and-pop restaurants for a long time more.”

A piled-high sandwich made by Lauren Lemos at Wax Paper in Chinatown.

The neon sign blazes at one of Wax Paper’s sandwich shops.

The first months of 2024 have already seen some of the region’s most popular and beloved restaurants shutter, including the Manzkes’ Bicyclette — a 2023 L.A. Times 101 List awardee — and generationally embraced beach haunt Patrick’s Roadhouse.

Francesco Zimone independently owns four U.S. outposts of Italy’s famous L’Antica Pizzeria da Michele, including Hollywood and Santa Barbara. He told The Times that in 2023 profit margin plummeted from 20% to 2%, causing him to operate with little salary for the year. In early 2024 he managed to expand to Long Beach and noted that the ability to order more ingredients in bulk has helped achieve better profit margins, and this year might see as much as 5% or 7%.

“[I’m] worried,” he said, “but certainly grateful.”

A brutal year for Los Angeles restaurants saw dozens of closings across the city. Inflation, actors’ and writers’ strikes and higher rent, utilities and labor costs all were cited.

A spate of new state and local legislation also is shifting the landscape for the industry in 2024, including increases in the minimum wage both at independent-restaurant and national-chain levels. Come July, surcharges for employee tips, health insurance and other benefits will be outlawed, with operators having to roll those into listed menu prices, should they still wish to charge them when customers have a low tolerance for higher prices.

Chefs and trade groups have complained that lawmakers leave them in the dark on the new laws’ details. Many said they wished more restaurateurs would be consulted by local, state and federal politicians when writing regulations that affect them.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“They should want to be looking for ways to help the restaurants recover and survive,” said Jot Condie, president and chief executive of the California Restaurant Assn., which represents roughly 22,000 of the state’s restaurants. “I think they should first start from a place of doing no harm, or in other words: Take your foot off our neck and don’t make it worse. Then look for ways to help restaurants survive.”

Multiple restaurateurs told The Times that the deck feels stacked against them.

“We do it because we love creating and we love bettering the lives of our guests through great food, great dining experiences, great spaces, great beverages,” said chef David LeFevre, who with a series of partners operates the Arthur J, Ryla, Fishing With Dynamite, Manhattan Beach Post and more.

“We’ve had restaurants that have struggled at times and it’s really tough, especially when you consider what restaurant owners put into it,” he added. “They’re not just borrowing money from people, they’re putting a lot of their own personal assets — sometimes all of it — into it.”

The cost of doing business

In January Uyên Lê took to social media to share that the prices at her Vietnamese restaurant in Silver Lake would have to increase for the first time in a year and a half. Inflation and other rising costs left her no other choice.

Since launching Bé Ù in 2021, the chef-owner noted that the restaurant’s cost of ingredients and packaging had increased by between 35% and 50% — and sometimes more.

“Vendors do not hesitate to raise their prices regularly on products,” she wrote, “and we are often very reluctant to pass those heavy costs on to our guests. … I am sure you understand considering the sticker shock most of you probably experienced at the grocery store lately.”

Though the Consumer Price Index, compiled monthly by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, noted only a slight increase from February to March, prices are up roughly 25% over the last four years, causing customers to tighten their budgets, especially when it comes to food. The price of eggs, for example, rose 4.6% in March.

For many L.A. restaurants, including Botanica in Silver Lake, solvency is more elusive than ever because of the elevated costs of doing business.

These cost increases, at the large volumes necessary for restaurants, can hurt the bottom line, but chefs and restaurateurs routinely fear raising prices out of concern that diners will stop coming when they see their favorite items have increased by even as little as 25 cents.

“The truth is,” Lê said in January, “this is a really tough business where the margins are razor thin, the predictability is very low, and the chances of catastrophe are high.”

Even fluctuations in gas prices can be disastrous.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Andy Kadin opened a Glassell Park deli in 2022, an evolution of his longtime bread bakery of the same name, Bub and Grandma’s. But his bakery wholesale accounts still comprise a large portion of his profits, with five bread delivery vans driving around the city daily, dropping off loaves to some of L.A.’s most lauded restaurants, cafes and grocery stores.

When the cost of gas passed $6 per gallon last year, the thousands of miles driven weekly equated to thousands of dollars each week. Kadin raised his delivery fees to compensate for higher gas costs; drivers’ insurance costs also increased, and he began inquiring about outsourcing delivery services to designated delivery companies. It’s something he’s still considering. (California’s gas prices currently average $5.305 per gallon as opposed to the national average of $3.636, according to the American Automobile Assn., with select regions in the state seeing “eye-popping price increases” this year.)

The war in Ukraine also affected the cost of U.S. flour. Should it rise again, the baker said that his operation will have to raise prices.

“There are thresholds that once they go over that, people aren’t going to pay $12, $15 for a single loaf of bread,” he said. “I hope we don’t get there. If we do, we’re going to have to get very creative and have to do more with less.”

And of course there’s the entire precarious ecosystem of local restaurants: If a large percentage of Bub and Grandma’s bakery and retail is restaurant wholesale, and many of his clients close due to their own struggles, that affects the bottom line for Kadin as well.

“It’s very hard to quantify exactly why things are so tight, because the flour prices are staying relatively in place,” he said. “It’s hard to track what else is eating up the cash. But everything has sort of steadily climbed up, including sales on our part; we’re at our highest sales we’ve ever had, we should probably be up over 10% in profit, but we’re not.”

Diversification, he said, is how he plans to combat it.

In late April he debuted “BG Nights,” in the hope that live jazz, new small plates and beer and wine will bring in more revenue, which he said is already proving successful. The only way to really continue, Kadin said, is to keep growing.

“It’s not solely the format that we thought it was going to be out of the gates,” he said. “It has to be a more comprehensive endeavor than what we were doing.”

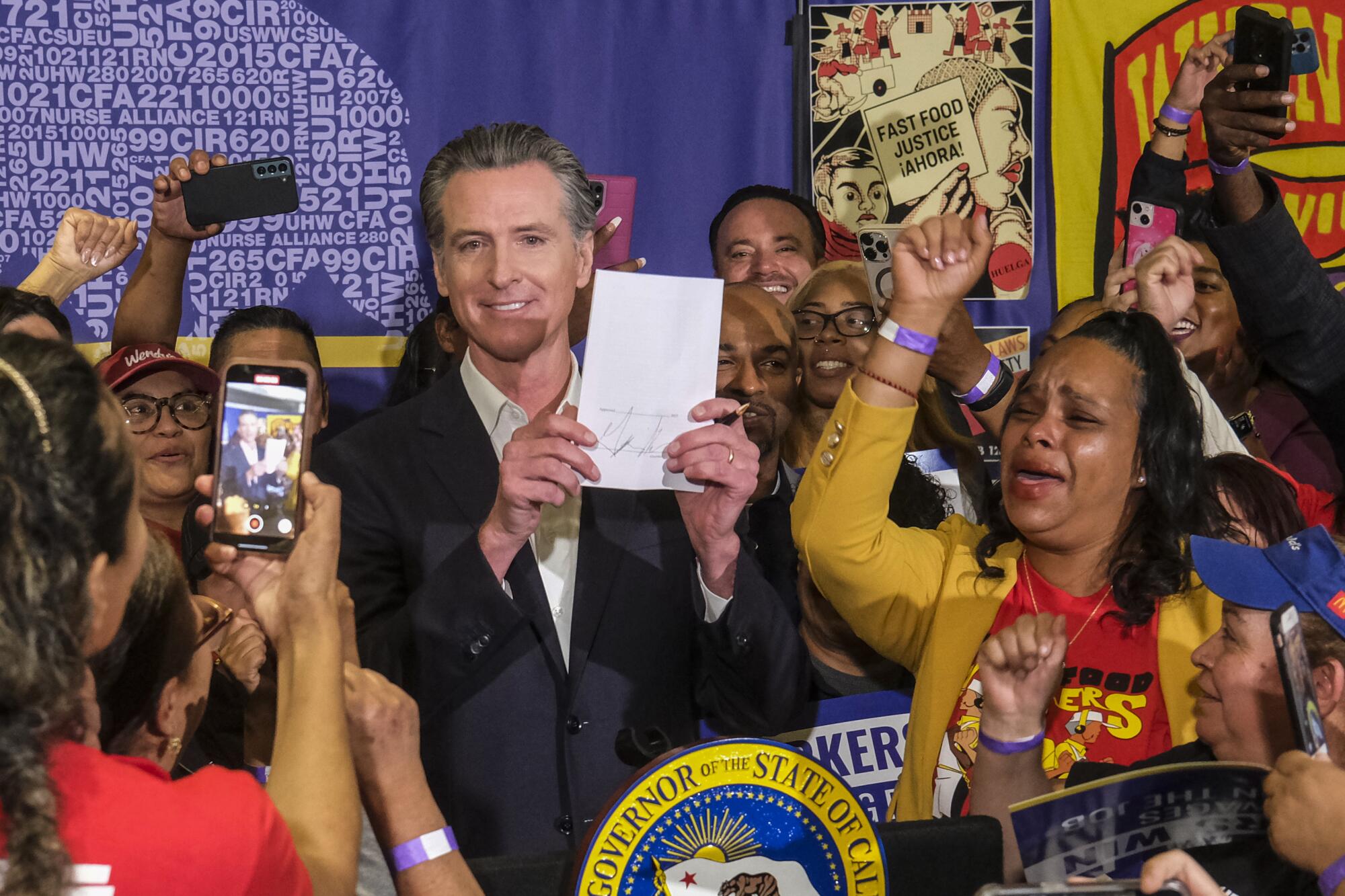

The wage rules change

Minimum-wage laws also are buffeting the restaurant industry like never before.

Federal minimum wage remains at $7.25 per hour, as it has for years, but in 2024, 25 states either saw their minimum wage increase or expect to increase it by the end of the year. This includes California, which in January bumped its hourly minimum wage from $15.50 to $16. It falls just behind Washington, D.C., and Washington state, at $17 and $16.28, respectively, as the highest statewide minimum wage in the country.

The city of Los Angeles is set to increase its minimum wage to $17.28 per hour. Other localities, such as Long Beach, will see wage increases for specialized fields later this year.

For many, local and statewide raises signify the hope of livability in some of the most expensive cities in the country. But multiple restaurateurs view raising wages as a financial kneecapping in an industry already surviving on barely-there margins.

Some of the most vocal concerns from the industry arrived with AB 1228: On April 1 the new California law increased minimum wage for fast-food chain workers by nearly 25%, bumping hourly pay to $20 for restaurant locations with more than 60 outposts in the U.S. and affecting an estimated half-million workers. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, roughly 200,000 of them are employed in L.A. and Orange counties alone. In December hundreds of Pizza Hut franchises announced they would lay off more than 1,100 delivery drivers, shifting to delivery apps like Uber Eats. Many franchisees have already raised prices, while some have begun implementing self-serve kiosks and AI to limit human staff.

“Gas isn’t going down, rent isn’t going down,” Mysheka Ronquillo, a cashier/cook at a Carl’s Jr. in Long Beach and a leader with the Fight for $15 and a Union in California, told The Times in February. A new statewide union of fast-food workers formed to advocate for annual wage increases and protections such as hourly minimums, along with existing trade unions, are celebrating AB 1228 as a victory.

“L.A. is the center for the working poor,” said Unite Here Local 11 co-president Ada Briceño. “Many people in the low-wage industry are one paycheck away from homelessness, or already couch-surfing or already live in their cars.”

Briceño said that most of the push-back that United Here Local 11 — which represents more than 32,000 restaurant and bar professionals, hotel workers and beyond — has noted regarding wage increases and other employee benefits stems less from small businesses and more from “corporate greed” by larger entities.

In March Long Beach passed a measure that increases qualifying hotel employees’ hourly minimum wage from $17.55 per hour to $23 beginning July 1, and incrementally, annually, to $29.50 per hour by July 2028. Prior to the vote, Briceño said that roughly 160 small businesses in Long Beach signed pledges to the union in support of minimum-wage increases that would affect their workers. According to Briceño, higher wages don’t necessarily equate to a halt in business; where she said they have seen a crush of new-business permits is in the city of West Hollywood, which two years ago voted to raise its minimum wage, now at $19.08 per hour — the fourth-highest in the country.

“We see that in areas where we have the highest wage increase — for example, West Hollywood — have a boom in business,” she said. “I think that’s really important.”

But multiple West Hollywood restaurateurs said the minimum-wage increase and paid-time-off requirements forced them to limit hours, raise prices or cut staff entirely. Industry veteran Craig Susser operates celebrity hot spot Craig’s in West Hollywood. He recently told The Times that in order to financially offset the increase in minimum wage, he had to reduce the number of servers from 12 to nine, and sometimes to eight.

The end of surcharges

The industry is bracing for impact. That’s because on July 1, California outlaws surcharges or “hidden fees” in restaurants and bars.

The new law applies to a range of services, including travel booking and concert tickets. But unique to the service industry is the fact that many restaurants use service charges to balance pay discrepancies between front-of-house employees, such as servers, who traditionally garner tips, and the back of house, such as cooks and dishwashers, who do not. They are often also used to help pay for employee healthcare and other benefits.

Several restaurants were scrutinized and legally challenged this year for their use of surcharges, including Jon and Vinny’s and Found Oyster. Last month Perch came under fire for charging a 4.5% “security” fee. Frustrated diners have taken to Reddit and written to the L.A. Times to voice their dismay.

“These deceptive fees prevent us from knowing how much we will be charged at the outset,” Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, who co-sponsored the measure, said in a statement the day the law was signed. A representative for the attorney general told The Times in February that restaurants and bars are advised to roll existing surcharge percentages into the listed menu prices come July 1.

“Every restaurateur that I know who cares in this industry is using it in a way that is so immensely appropriate and responsible and forward-thinking that if it was to go away, it would be really crippling to everybody,” Kato restaurateur Ryan Bailey told The Times earlier this year. “We have people who have progressed from entry-level positions into management positions because they felt that we are taking care of them and care about their financial stability.”

At Kato, the No. 1 restaurant on the 2023 L.A. Times 101 List, Bailey said an 18% service charge helps cover an employee benefits package that includes mental, medical, dental and vision services, and to offer a 40-hour workweek.

Bailey, who heads Kato’s management operations but also has served as a business consultant to other restaurants, said operators — in an effort to not raise prices — might offset a ban on service charges by cutting staff from 30 to 22, or by requiring more staff contributions for insurance packages.

Nonprofit Regarding Her provides educational and financial programming to help female chefs, leaders and entrepreneurs in a restaurant industry that has never been easy for women and is itself struggling.

“For us, it’s definitely going to be a challenge,” he said. “I’ve heard certain operators say that it’s going to be very detrimental for the staff, that what they’re offering they might not be able to offer anymore.” He said he has heard some owners mention cutting select benefits to employees once the surcharge ban begins.

Bailey, like many others, urged legislators and trade groups to provide clarity on the law before it takes effect this summer. “When there’s lack of clarity around an issue, that opens up the potential for lawsuits, which then opens up the potential of a huge loss for a restaurant, and potentially the closure of it,” he said.

Last month prolific restaurateur Dustin Lancaster — whose hospitality group operates 13 concepts in L.A., plus Covell’s reservation-only Sidebar — preemptively did away with surcharges at his businesses that previously enforced them, folding the 4% service charges into his menu prices at L&E Oyster Bar and El Condor.

“It’s not worth the conversations, confusion and pushback once the bill is enacted,” he told The Times, adding, “It’s sort of a ‘pick your poison.’ Customers’ complaints or pushback have been almost nonexistent regarding the price raises, but perhaps that’s because everyone has raised prices and they just expect to pay a lot more when going out. At the end of the day, not knowing how this would shake out seemed pragmatic to just make the switch sooner than later.”

A shift in dining preferences

“People are spending more,” said chef David LeFevre. “But they’re not spending it at restaurants.”

LeFevre said he’s heard from many patrons that they chose to invest in their immediate surroundings during the pandemic. Now they want to reap the benefits of the work they’ve put into upgrading their homes and prefer to spend time there — especially later in the evening.

According to multiple chefs, the pandemic also shifted the hours Angelenos tend to dine.

“I’ll tell you what people don’t do anymore: They don’t go out to dinner late,” LeFevre said. “If you look at 2019 compared to today, if you look at reservations after 8 o’clock, it’s dismal. … At the restaurants, the reservations after 8:30 [p.m.] are 50% of what we used to do, and that is a really big aspect of it.”

The pandemic also altered where diners spend their money; after not traveling for a few years, LeFevre and others say many diners are opting to save to travel and then spend money on food in far-flung locales as opposed to dining out locally. Despite rising rates, the International Air Transport Assn. found that demand for travel this March was up 13.8% compared with March 2023; for international travel, it rose 18.9% in that time.

The shift in post-pandemic diner expectations also is something LeFevre and his team still contend with, especially when it comes to outdoor dining.

While all of the chef’s restaurants weathered the pandemic and remained open, their experiences and successes differed; some had parklet dining, others didn’t, but it proved to be crucial.

Many restaurateurs heralded the provision when indoor dining bans heavily affected business; Casa Vega owner Christy Vega told The Times that the L.A. Al Fresco program saved her family’s Sherman Oaks restaurant, calling it “wildly vital to our survival.” According to a survey by the city, more than 81% of business owners interviewed said they would have permanently closed had it not been for the program.

Some cities and counties pushed for parklet dining’s longevity, while others sought to disband it. At the statewide level, AB 1217 has extended parklet dining and other pandemic-era provisions into mid-2026.

In December, the L.A. City Council voted unanimously to make its program permanent. In early 2023 Manhattan Beach had already voted unanimously to end the beach city’s use of temporary parklet dining areas, giving business owners 10 days to remove them.

“Maybe have an exit plan that’s a little bit less like yanking the Band-Aid off and more like, all right, let’s use a smaller and smaller Band-Aid over time so you can adapt,” LeFevre said, “versus, ‘We’re going to do everything and then we’re going to take it all away.’ People don’t come to California or to the beach communities to dine inside.”

More than a year later, Manhattan Beach’s Outdoor Dining Task Force is still weighing proposals and business plans to integrate al fresco dining back into its restaurants and bars.

Through it all LeFevre remains hopeful. He has to, he says, to keep going. In June he plans to debut a Mediterranean seafood restaurant called Attagirl in Hermosa Beach with Fishing With Dynamite chef Alice Mai.

“Sometimes you have to change the lens you look at it through,” LeFevre said. “I do think that there are some big challenges, especially in California, that are going to continue to come up ... but there’s a lot of optimism because I know how great it can be.”

The closure of Nickel Diner and forced move of Little Tokyo’s Suehiro Cafe will change the feel of downtown L.A.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.