Merce Cunningham ‘Night of 100 Solos’: How L.A. organizers pulled off a dance coup

- Share via

“Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event” was a celebration of Merce Cunningham on what would have been the 100th birthday of one the most pioneering and influential choreographers in contemporary dance.

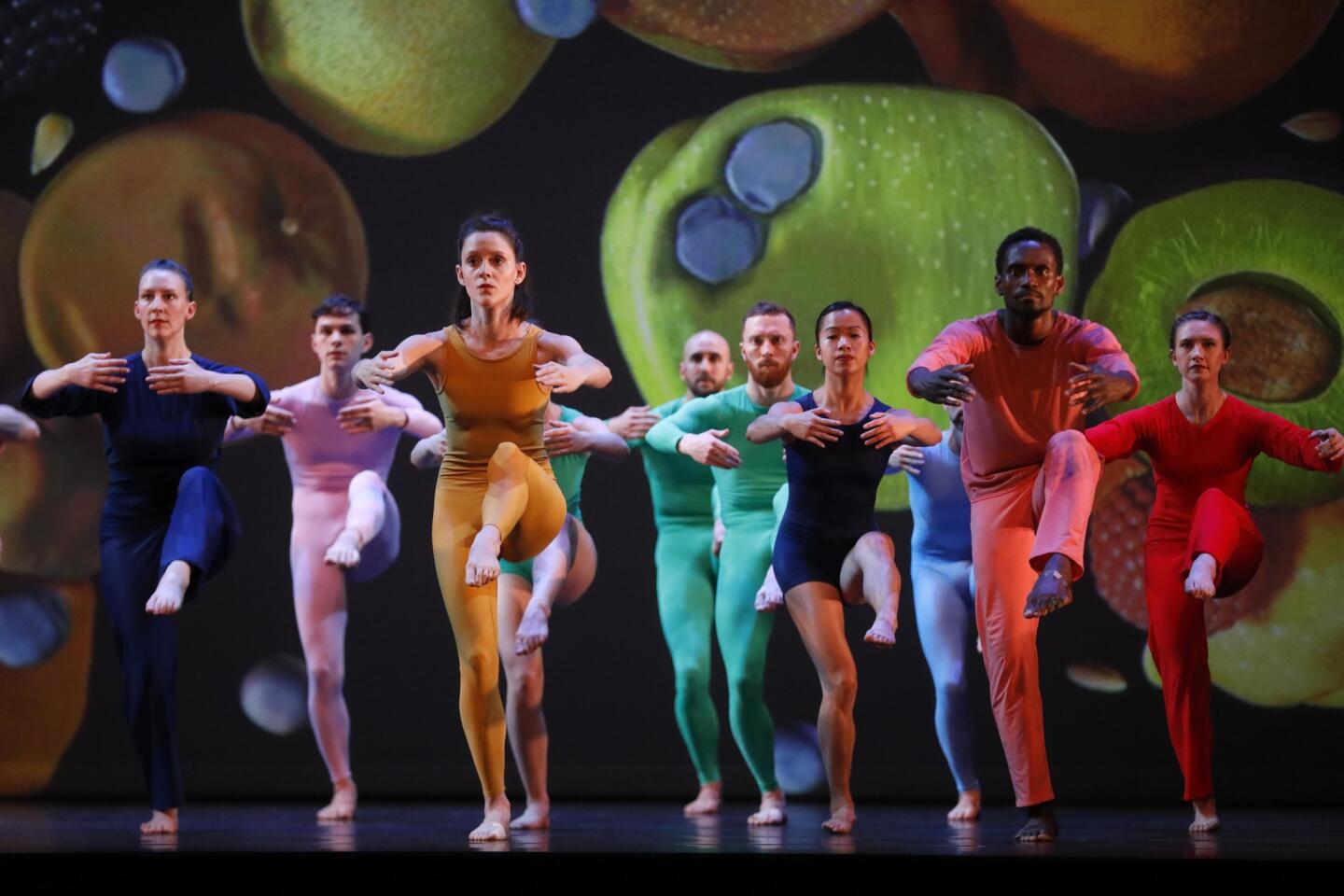

Billed as the largest Cunningham event ever, “Night of 100 Solos” took the form of three performances Tuesday, one at the Barbican in London, another at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York and the last hosted by the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA.

Organizing “Night of 100 Solos” in L.A. — a performance that included 25 dancers and 100 solos across 90 minutes — was a massive puzzle, said Andrea Weber, a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 2004 to 2011 and the primary stager for the L.A. event.

REVIEW: Times critic Mark Swed on ‘Night of 100 Solos” »

Almost two years ago, CAP UCLA’s executive and artistic director, Kristy Edmunds, began talking to Cunningham centennial producer and former executive director of Cunningham’s dance company, Trevor Carlson, about meaningful ways to celebrate the 100th birthday.

As former consulting artistic director of the Park Avenue Armory in New York and artistic director of the Melbourne International Arts Festival, Edmunds knew Cunningham’s work deeply. Los Angeles was a logical choice for “Night of 100 Solos,” she said.

“These were all cities that were very important over the progression of his choreographic life,” she said.

Edmunds curated the L.A. event by mimicking the way Cunningham worked with his collaborators. She invited artist Jennifer Steinkamp to develop the set design, a rich computer video backdrop of flora and fauna.

“These would have been the kind of things, had Merce known her work, they would’ve collaborated,” Edmunds said.

Edmunds also played a role in casting dancers for the L.A. show and raising money for the event. She and the Merce Cunningham Trust discussed “casting quite a few dancers who had not worked with Merce but were extraordinary.”

Initial conversations with producers and primary stagers began in November 2017. The group started inviting dancers and researching solos about a year ago.

Weber spent months digging through the trust’s dance capsule, watching around 70 works on video to select solos for the event. She was committed to including a comprehensive array of Cunningham’s choreography, from the 1950s to the 2000s. (Cunningham died in 2009.)

Weber eventually selected about 10 solos, from 20 seconds to five minutes, from each decade. The oldest is from Cunningham’s “Dime a Dance,” a work that premiered in 1953 at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

Weber touted the diversity of the L.A. cast, with dancers ranging from their 20s to their 60s. “Our cast is a little different than the other casts in that we have dancers from all over the United States,” she said.

Most hail from outside L.A., including New York, Houston and Seattle. None was a member of Cunningham’s troupe, and about half had never taken a Cunningham class.

Since the company disbanded in 2011, “one of the things we’ve really focused on is that Merce’s legacy can live on in different bodies and different dancers,” Weber said.

Some of the performers Tuesday had danced Cunningham works with other companies or learned the technique in school.

“In a few instances, we were able to pull a solo that an individual already knew, which was important for being efficient in the rehearsal,” Weber said.

In January, dancers began learning their solos in L.A., Chicago and New York from Weber and other Cunningham alumni.

A former member of the Lucinda Childs Dance Company, cast member Katherine Helen Fisher now directs Safety Third Productions, an L.A.-based media company. She performed three solos for the event, from Cunningham’s “Variations V” (1965), “Fluid Canvas” (2002) and “Tread” (1970).

Learning “Variations V” from Weber was especially exciting, Fisher said. The two watched a black-and-white recording of the work from the 1960s or 1970s in Hamburg, Germany, and one of the dancers from the original recording — now in his 70s — assisted with the staging.

“It’s like a really meaningful feeling of lineage and heritage there that I really enjoyed,” Fisher said.

Fisher hated her first contact with the Cunningham technique in college. “It felt really narrow and kind of masculine to me in a way that I didn’t feel like was accessible to my body,” she said.

But returning to the work as a mature dancer, after being asked to perform in “Night of 100 Solos,” gave the performer a new understanding of the choreographer’s work.

“I started studying the Cunningham technique for the first time in my adult life,” she said. “Seeing the nuance and the release ... it doesn’t feel rigid to me at all anymore. It feels like really expansive.”

ARCHIVES: Merce Cunningham dies at 90; revolutionary choreographer »

For months, Weber asked dancers to send videos so she could monitor their progress with the solos. And in true Cunningham methodology, the dancers rehearsed in silence, so they would hear the live music accompaniment only when they performed.

Weber and an associate stager, former Cunningham dancer Dylan Crossman, relied on another Cunningham technique — chance operations — to provide a sense of structure for the show. Chance was a fundamental choreographic tool for Cunningham, who often flipped coins or rolled dice to decide how to combine movement phrases.

Weber and Crossman used chance to divide the 100 solos into five sections. Chance helps with decision making, Weber said. “You’ll think outside of your own box.”

But with the sheer number of solos, the duo had to do a bit more calculated arranging. They filled five poster boards with 100 sticky notes to help figure out the logistics of the show order and cues.

It wasn’t until Saturday, when the cast and stagers rehearsed together for the first time, that the pieces truly began to fall into place. The group had to “work like clockwork” to finish, and it was a feat to teach all the dancers their cues, Weber said.

There was room for hiccups, though. The true magic of the show was honoring the spirit of Cunningham.

“It’s not necessarily going to look like what a Cunningham dancer would have done,” Weber said. “But I think that the work is really true. I think the integrity is there, and I think that it’s a real celebration of Merce.”

SPRING DANCE PREVIEW: What to see in SoCal this season »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.