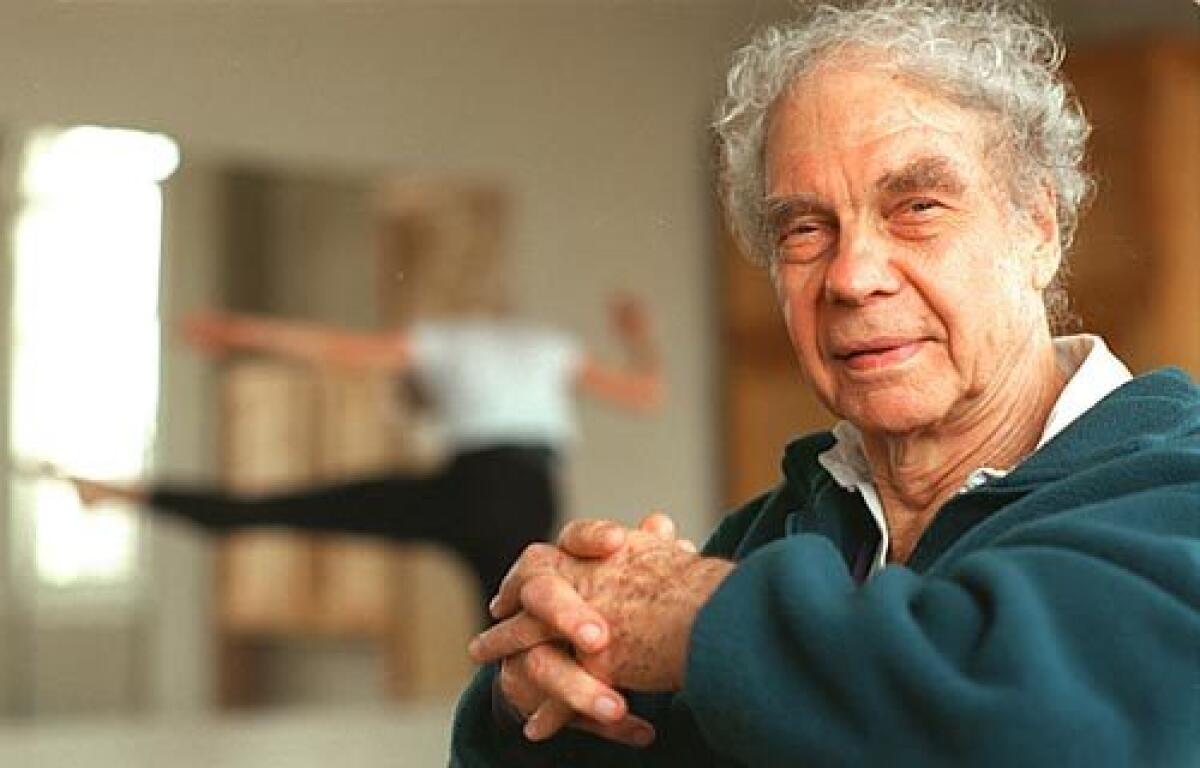

Merce Cunningham dies at 90; revolutionary choreographer

- Share via

Merce Cunningham, arguably the greatest, most pioneering and widely influential contemporary choreographer of the past half-century, has died. He was 90. A seminal artist whom fellow choreographer Bill T. Jones called “the champion in the struggle to say that dance is its own primary language, with its own agenda and criteria,” Cunningham died Sunday at his home in New York of what his dance foundation said were natural causes.

Cunningham challenged nearly every assumption about how dances are made and perceived. “Dancing is a spiritual exercise in physical form,” he wrote in 1952. “What is seen is what it is.” Evolving over the years from a fluid and even balletic modern dance style to a technique emphasizing sudden, virtuosic changes of direction, balance and body focus, Cunningham refused to interpret music, tell stories, depict characters or accept the idea of the choreographer as a kind of all-knowing god.

Instead, he used chance -- throwing dice, flipping a coin -- to help him discover possibilities beyond his imagination, insisting that the choreography, score, scenic design and costumes for a work should be created independently and come together at the final rehearsals or first performance.

“Cunningham was fresh and novel when he began making dances in 1942. He was fresh and novel when revealed his last one in April, on the occasion of his 90th birthday,” Times music critic Mark Swed said Monday. “He changed dance, and, in his continual need for innovative scores, he helped change music as well. He always wanted to be one step ahead of everyone else so he could learn something new.”

Refusing to accept center stage as the sole magnet of attention, Cunningham divided theatrical space into independent zones of action, believing that dance should reflect a world in which people constantly monitor many simultaneous activities. “The society is so fragmented . . . “ he told The Times in 1997, “and I see no reason why it shouldn’t affect the way one makes a dance.”

Finally, he built a company that not only showcased his theoretical and collaborative innovations but also made them exciting, surprising and deeply persuasive.

“Every piece is so different in its dynamics and space and variety of language,” former Kirov Ballet superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov told Newsday in 1999. “No words can describe my admiration and fascination with this man.”

Dancing at a young age

Mercier Philip Cunningham was born in the lumber town of Centralia, Wash., on April 16, 1919. At 8, he could perform the Sailor’s Hornpipe, a solo dance that mimicked the work a sailor did on a boat. At 12, he began studying with former vaudeville and circus performer Maude Barrett.

“I started as a tap dancer,” Cunningham said in a 2005 Times interview. “It was my first theater experience, and it has stayed with me all my life.”

Like his father, Cunningham’s brothers became lawyers, but Cunningham studied acting in the Cornish School of Fine Arts in Seattle, soon switching his major from theater to dance. There he met composer John Cage, who was soon to be his lifelong personal and professional partner.

Further studies at Mills College in Oakland and at the Bennington School of the Dance in Vermont led to his being invited to join the Martha Graham Dance Company in 1939. For the next six years, major roles were created for him in such Graham masterworks as “El Penitente” (1939), “Letter to the World” (1940), “Deaths and Entrances” (1943) and “Appalachian Spring” (1944).

In 1944, Cunningham and Cage gave their first joint concert in New York (six solos to Cage’s music), and the following year Cunningham left Graham to freelance. He formed his own company in 1953, allying himself with leading members of the American avant-garde: painters Andy Warhol, Frank Stella and Jasper Johns, among others. Robert Rauschenberg became his first resident designer, and Cage served as music director.

Although Cunningham still choreographed to music as late as 1953, he had already come to believe in creating dances without reference to, or even knowledge of, their accompaniments. From Cage, he also developed a commitment to chance procedures.

“When you work on something that you don’t know about, how do you figure out what’s right for that moment?” he asked rhetorically in the 2005 Times interview. “Using chance can be a way of looking at what you do in another way without depending always on your memory. It helps something else to come out that otherwise you wouldn’t have known about.”

His relationship with Cage deepened into what people who knew them call one of the great, if sometimes turbulent, love stories of the age -- one inseparable from the couple’s revolutionary achievements as artists. “They amazed me by their air of living for art and freedom,” critic Alfred Kazin wrote.

But it wasn’t a time when anyone, anywhere, celebrated what amounted to a same-sex marriage, and, what’s more, the personal style cultivated by Cage and Cunningham left their story largely untold. “I don’t think I was guarded about my personal life,” Cunningham told the Guardian newspaper in 2000. “John and I were together. We did our work together. We traveled together. What more is there to say?”

Tomatoes and acclaim

In 1964, Cunningham’s company made its first international tour. In Paris, “people threw things at us -- eggs and tomatoes,” original company member Carolyn Brown told the Guardian in 2000. “During the interval, they went out to get more.” The reception in Venice was markedly better, and in London the company became a sensation.

London put Cunningham on the map -- in the United States as well as abroad. “No performances were as crucial to the company’s future as those in that first London season,” Brown recalled in a 2001 article she wrote for the New York Times. “It’s an old story, isn’t it? Artists, unappreciated in their own land, must cross the waters and prove themselves in the Old World before being sanctioned in their own New World.”

Cunningham returned to America as a recognized contemporary master, with new innovations to explore. In what he called “events,” for example, he took sequences from his existing repertory and strung them together to different music and new (or no) decor in free-form pure-movement cavalcades. He was still controversial within the dance community, but as British director Peter Brook wrote of the company in 1964, “the very things that are criticized, laughed at and ignored will only a few months later be imitated everywhere.”

Beginning in the 1970s, Cunningham worked extensively on dance-for-camera projects, often in collaboration with Elliot Caplan and Charles Atlas. Atlas’ documentary, “Merce Cunningham: A Lifetime of Dance,” was released in 2000.

Technological growth

His interest in technology took him in a new direction starting in the early 1990s, when he began using computer animation as a preliminary stage in the choreographic process. “The computer allows you to make phrases of movements, and then you can look at them and repeat them, over and over, in a way that you can’t ask the dancers to do because they get tired,” he said in the 2005 Times interview. “And you can change it and they can’t get angry at you.”

“Very often you discover something that you think is impossible. You do it, you try it out -- and it is impossible. But while you’re doing it, you discover something else you didn’t know about. I always think there’s something else -- not necessarily that I’m going to find it, but I know there’s always something else.”

At the turn of the century, Cunningham experimented with futuristic motion-capture technology in a work titled “Biped,” putting live dancing in juxtaposition with projected imagery developed out of the digital manipulation of movement impulses. His growing expertise in computer choreography also allowed him to create and demonstrate moves that arthritis and other ailments kept him from executing himself.

Although the winding-down process was gradual, he essentially stopped performing with his company not long after Cage’s death in 1992. He did make occasional appearances in non-dancing roles. In 2001 he played composer Erik Satie in “Alphabet,” a radio play by Cage staged in a number of international venues. And in the 2002 revival of his 1965 dance piece “How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run,” he and company archivist David Vaughan read the stories that Cage wrote as accompaniments for the dancing.

His dance company continued to tour and perform his work, and engagements were scheduled into 2011.

A living legacy

Last month, the Cunningham Dance Foundation announced a “living legacy” plan to preserve the choreographer’s work after his death. The plan called for his dance company to embark on a two-year international tour capped by a New York performance for which tickets would sell for $10 apiece. The nonprofit Merce Cunningham Trust was set up to maintain his body of work.

Funding his company was never easy, but honors and awards became plentiful as the dance world began to accept and celebrate Cunningham’s innovations. In 1982, the French government made him a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in the Legion of Honor. In 1984, he was named an honorary member of the American Institute of Arts and Letters, and he was chosen the following year for the Kennedy Center Honors, the Laurence Olivier Award and a MacArthur Fellowship.

Other major honors included two Guggenheim fellowships (1954 and 1959), the Dance Magazine Award (1960), the Capezio Dance Award (1977), the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award (1982), the National Medal of Arts (1990), the Wexner Prize (with Cage, 1993), the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale (1995), the Handel Medallion from the mayor of New York City (1999), a special Nijinsky Prize (2000), the Arts and Business Council Kitty Carlisle Hart Award (2002) and the Edward MacDowell Medal (2003).

Cunningham collaborated on two books about his work -- “Changes: Notes on Choreography” (1968) and “The Dancer and the Dance” (1985) -- along with creating “Other Animals” (2002), a book of his drawings and journals.

According to his foundation, Cunningham is survived by a brother, Jack Cunningham of Centralia, Wash.

Segal is a former Times staff writer.

Appreciation Times music critic Mark Swed remembers Merce Cunningham pushing boundaries until the end. CALENDAR, D1

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.