Review: For Merce Cunningham’s 100th birthday, an exceptional ‘Night of 100 Solos’

- Share via

Merce Cunningham died 10 years ago at 90. He was easily the greatest choreographer of the second half of the 20th century and a teeny bit into the 21st. He left behind an enormous body of work. He passed on new techniques of movement to generations of dancers, while his profound ways of thinking about the meaning of movement have much broader implications for art and how we might better look at life.

Yet all of it, in a manner of speaking, vanishes into air, as Cunningham himself was known to almost do as a young dancer who didn’t leap so much as seemingly fly. He questioned everything, legacy included. He also made his wishes known that when he died, the company would continue for two years (for the sake the dancers’ employment more than anything else) then disband. He stood for invention, not continuation.

That, however, didn’t mean the Merce Cunningham Trust was about to pass up one of the greatest legacies in dance since the dawn of Terpsichore. It celebrated Cunningham’s 100th birthday Tuesday night with the gargantuan “Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event.” Three 90-minute programs were presented that evening — one in London, another in New York and the third at Royce Hall presented by Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA. At each venue, 25 dancers took on a total of 100 solos Cunningham choreographed throughout his long career.

The programs were independently made, with individual choices for the solos (although there was overlap), musicians, costumes and decor. Each was streamed live at mercecunningham.org and will be archived for a limited time. Cunningham was never afraid to think big on the few occasions he could afford to, but never on this scale.

The dancers were chosen from different companies and walks of dance life and included former Cunningham company members dancing solos they learned from the master. Many more original Cunningham dancers served as coaches. A former Cunningham musician was in charge of putting together a pit ensemble in each city.

The main idea was to follow the practice that Cunningham had employed in what he called “Events.” Bits of his dances, chosen by chance, were thrown together. Music and decor were independent, and everything came together only at the first performance.

The logistics behind “100 Solos” were mindboggling. The planning took about two years. The result in all three cases was exceptional, but particularly so at Royce, where the show was slightly more ambitious than elsewhere. I cannot find a metaphor for what it is like to witness what this was — a great life lived in dance being re-created without any sense of it being re-created, but actually being lived.

‘NIGHT OF 100 SOLOS’: How one night took month upon month of planning »

It was nothing Cunningham would have done, and it even violated some of his ways of working, yet it was true to his spirit. In that I would like to think that it is what he would have wanted. But since we can’t know that, what we can know is that “100 Solos” was Cunningham’s world as simply overwhelming experience.

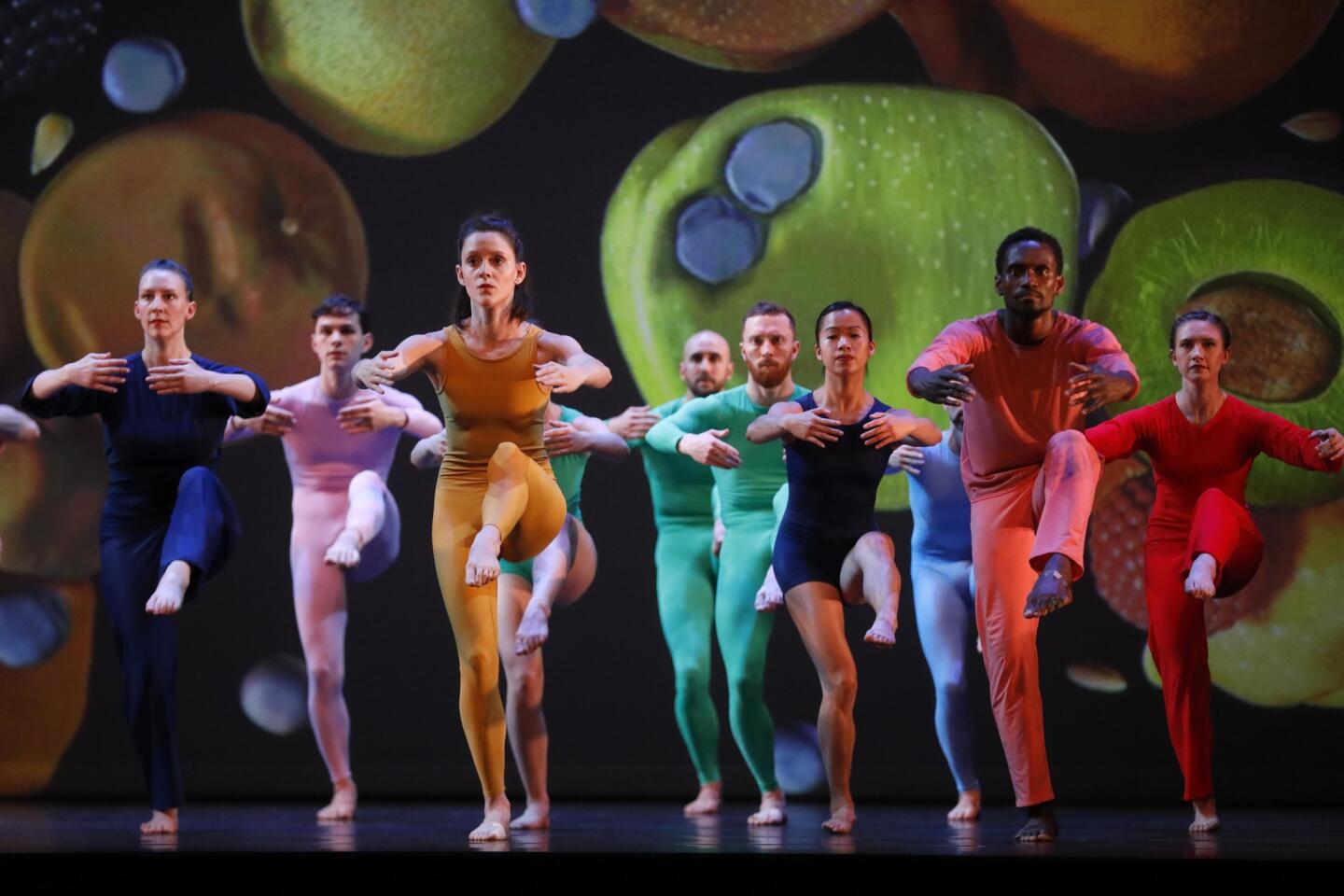

For Royce, the installation artist Jennifer Steinkamp created a gorgeous computer video backdrop of flowing, fluttering forests and flowers and fruits and linens that captured Cunningham’s often ignored Northwestern roots. (He was from Washington state, although his career was in New York.) The screen and brilliant colors were enough to swamp the dancers. But the daring visual effect thrilled a choreographer who worked with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and was inspiration for the dancers to extol a greater presence.

The dancers included the kinds that Cunningham typically employed but also body types he didn’t. He had few African Americans, and no African American women, in his company, and there were several at Royce. But the fact is that all dancers’ bodies today are different than they were a half-century or more ago, muscles now sculpted in ways not seen before. And period practice is the last thing that Cunningham wanted.

Focus, stillness though movement, movement that seems undoable by the human frame, intensity in every muscle — these were the heart of Cunningham’s work and are something every dancer benefits from. It was especially stirring to witness young dancers for whom the solos seemed like a revelation.

The performance was a one-of-a kind parade. One, two, three, four or more solos were happening at any moment. They were as unrelated as different people walking down the street might be, but to the viewer they made a scene meaningful.

Around halfway through, everyone came onstage and froze in a different position for John Cage’s silent piece, “4’33”.” The video froze as well, while the music curiously continued. It was a wrenching four minutes and 33 seconds of environmental art — the earth stopping turning yet the harmony of the spheres unaffected, thus increasing the value of the ground on which we stand.

But mainly this was Cunningham split into 100 Cunninghams fertilizing not just dance but our awareness of movement, the primary symbol of life.

The music was full of electronics and electricity, led by the Chicago sound artist Stephan Moore, who had been a sound engineer in the last years of the Cunningham company. He effectively but originally channeled the kinds of electronics that characterized the approach of David Tudor and Takehisa Kosugi when they had been Cunningham’s music directors. Whereas Cunningham rarely employed women musicians, Moore invited four spectacular L.A. women avant-gardists to join him.

So many things could have gone wrong with this project that involved multitudes to pull off, all for a one-off. For a couple of months, you can get a sense of why online. That video will then vanish into thin air too. But it will not be, in the same way that Cunningham is not, forgotten.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.