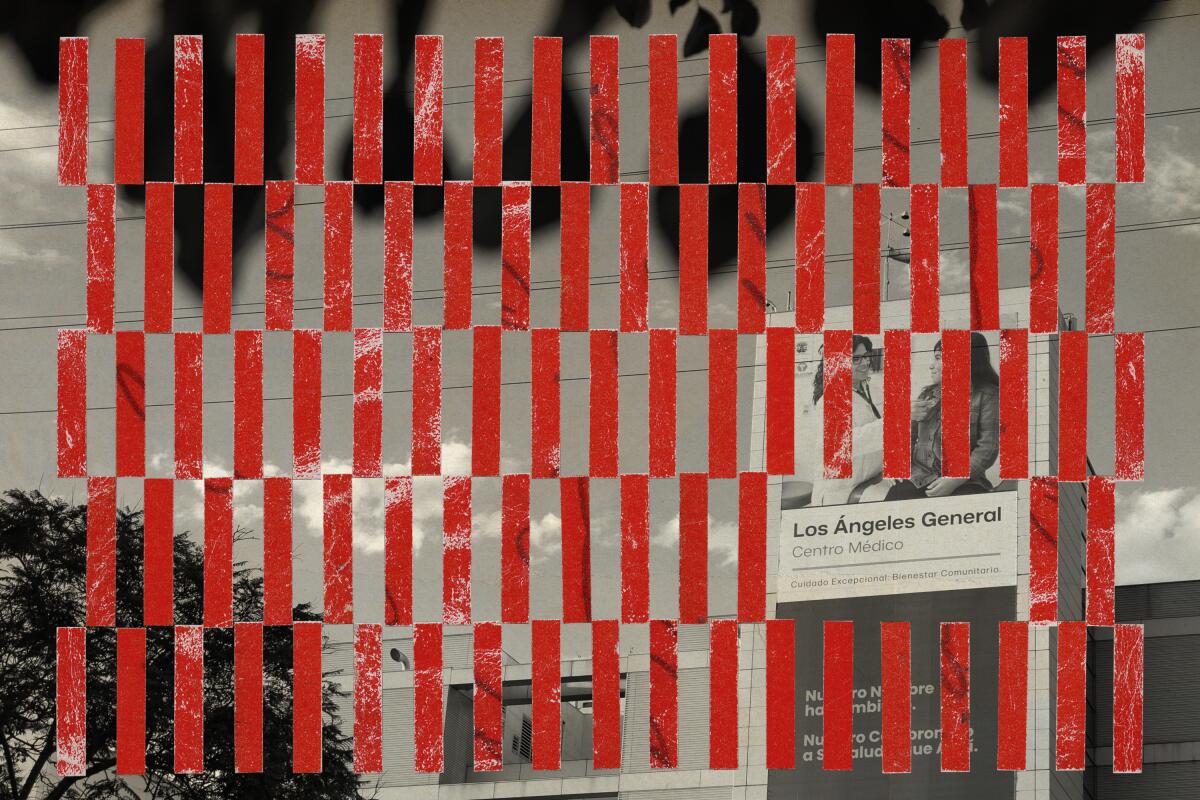

Why high rates of restraint at L.A. General haven’t raised alarms

- Share via

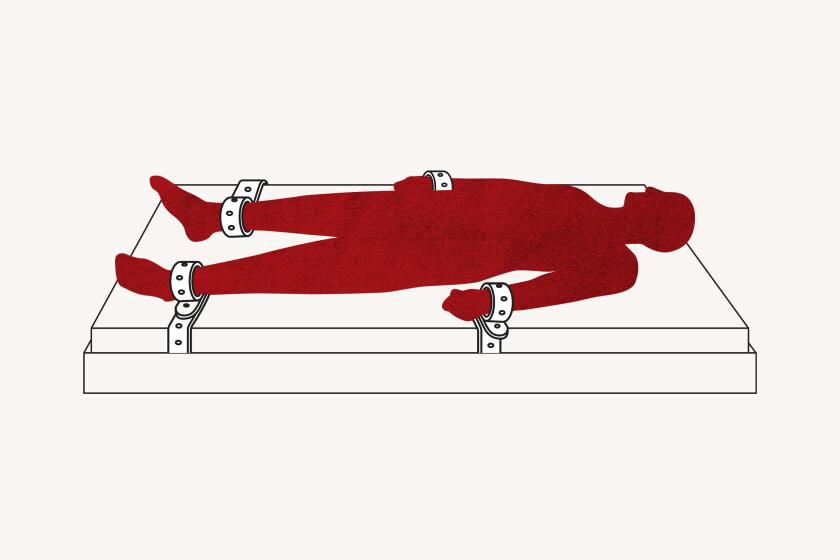

Los Angeles General Medical Center restrains inpatients in its psychiatric unit at a rate higher than any other hospital in California — and more than 50 times the national average for inpatient psychiatric facilities, a Times analysis of federal data from 2018 to 2021 found.

So why haven’t regulators raised alarms over these sky-high restraint rates?

High rates of restraining psychiatric inpatients do not automatically spur any action by federal authorities, California hospital regulators or the Joint Commission, a nonprofit agency that accredits L.A. General and many other hospitals. There is no industry standard on what amounts to a concerning rate of restraint at a psychiatric facility.

Vincent S. Staggs, a senior scientist at the clinical research firm IDDI who has studied restraint rates at hospitals across the country, worries that as a result, hospitals could persist with approaches that result in “unacceptably high” rates of restraint “without realizing that their practices are extreme.”

“There just aren’t norms or guidelines ... for facilities to know what is an appropriate, or at least a typical, rate,” said Staggs, who is also a former professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s medical school.

L.A. General’s inpatient psychiatric unit has restrained patients at a higher rate than in any other in California, a Times analysis has found.

The California Department of Public Health, which regulates acute care hospitals and acute psychiatric hospitals, does not track restraint use on psychiatric patients at the hospitals it licenses despite a 2003 law ordering state regulators to do so.

The law required the state agency to track restraint only if its budget could accommodate it, but no additional funds were ever allocated to the agency, according to the state public health department. An agency spokesperson said it does not monitor federal data on restraint to initiate hospital investigations.

The state agency also said it does not receive monthly reports filled out by hospitals on restraint use. That stands in contrast to how another state agency monitors restraint rates at a different set of mental health providers, including psychiatric health facilities.

The Department of Health Care Services said that it does get those monthly reports for the psychiatric facilities that it licenses and would conduct a “focused compliance review” if one of them documented a high frequency of restraints. Federal data show that DHCS-regulated inpatient facilities all reported relatively low levels of restraints in recent years.

Hospitals may be faulted by state Department of Public Health investigators for specific lapses involving restraints: The agency carries out routine relicensing surveys and conducts inspections in response to complaints or when hospitals report serious issues that affect patient care.

For instance, state investigators looking into a complaint recently faulted L.A. General after finding patients in a medical unit on its main campus with all of the side rails on their beds up, a restraint practice for which it did not have a written policy, increasing the risk it could be used inappropriately, according to the state findings.

L.A. General officials said government regulators had consistently found restraint use at its Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center in Willowbrook to be in line with state and federal rules.

Then there are hospital accreditors. County officials said a recent accreditation survey by the Joint Commission had not faulted restraint use at L.A. General and “gave us the highest praise for performance.”

The Times analyzed restraint data for psychiatric inpatient facilities that have been collected by the federal government since 2013.

But the details of that assessment are not available to the public. The county denied a Times request for the survey documents, and a spokeswoman for the accrediting agency said any information about a health organization that is not published on its website is confidential.

Restraint rates at L.A. General have soared despite the fact that decades earlier, driving down the use of physical restraints became an urgent focus for federal lawmakers and agencies.

In the wake of a 1998 series in the Hartford Courant, which tallied scores of deaths related to restraints and seclusion across the country, outraged lawmakers sought reforms. Government investigators called for new standards and safeguards, as well as regular reporting on restraint use.

Nearly a decade ago, federal regulators announced that information about restraint rates in psychiatric units would be readily available to the public online, empowering patients and their families to make “informed decisions” about their psychiatric care.

But that data itself can be faulty. Errors in the federal restraint data can go uncorrected for years, resulting in flawed information being provided to patients and families looking online at restraint data.

The Times found that federal authorities have publicly reported a dramatically lower restraint rate for L.A. General in 2016 and 2017 than in other years. The reason: The restraint hours were divided by a huge number of days spent by patients at the psychiatric unit, more than 20 times higher than in other years.

The U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which collects the data, and the L.A. County Department of Health Services, which submitted the data, each pointed to the other for the apparent error. The uncorrected data remain on a federal website that includes information about hospital restraint rates.

That leaves local oversight. In L.A. County, there was an effort more than a decade ago to press local hospitals to reduce how often they restrain psychiatric patients.

If you want to learn more about how regularly a local hospital uses restraint on psychiatric patients, and how those restraint rates compare with state and national averages, here’s where to look.

At the time, the county’s Department of Mental Health compared the frequency and duration of restraints at different hospitals, using monthly reports turned in by the facilities. Back then, L.A. General Medical Center, then known as L.A. County-USC Medical Center, was restraining psychiatric inpatients less often than other county facilities and several local private hospitals, department data show.

But in recent years, as the rate of restraining psychiatric inpatients at L.A. General soared, reducing restraint use “hasn’t been a focus” for the mental health department, said its director, Lisa Wong.

The agency still receives monthly reports on restraint use, but until recently it would dig deeper only if something “really stands out” or if a complaint were submitted, she said. A department spokesperson said the agency has been reviewing the reports every three years.

Wong said she decided to take a closer look last year, after The Times submitted requests for public records about L.A. General’s use of restraints. In March, she said, the department was setting up a system to review the data each quarter “so that we can spot a trend before it becomes a bigger deal.” As of late September, her agency had not implemented that new process, according to a department spokesperson.

Wong said that she felt satisfied with the explanations from L.A. General about its unusually high rates after learning that a small subset of patients drove up its restraint hours, among other factors.

Amid growing attention in healthcare to racial and ethnic disparities in treatment, researchers have found that in some settings, Black patients have been more likely than non-Black patients to be physically restrained.

L.A. General said its own internal analysis found that in its psychiatric unit, the racial and ethnic breakdown of patients who were restrained “largely mirrors” the makeup of the unit in recent years.

But the high rates of restraint at a hospital that disproportionately treats patients from marginalized communities — including Black people, unhoused people and people who have been incarcerated — trouble Patrisse Cullors.

Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter Global Network, recounted how more than a decade ago her brother Monte was reluctant to go to L.A. General for psychiatric treatment because he was terrified of being restrained.

She said he was restrained “multiple times” at the hospital, despite her urging staff there to avoid restraining him because of his past trauma.

“After that experience,” she said, “I’d never send him back there again.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.