- Share via

When he came home from the hospital, Marcelus Laidler began to wet the bed. His mother noticed he seemed leery, questioning everything she did.

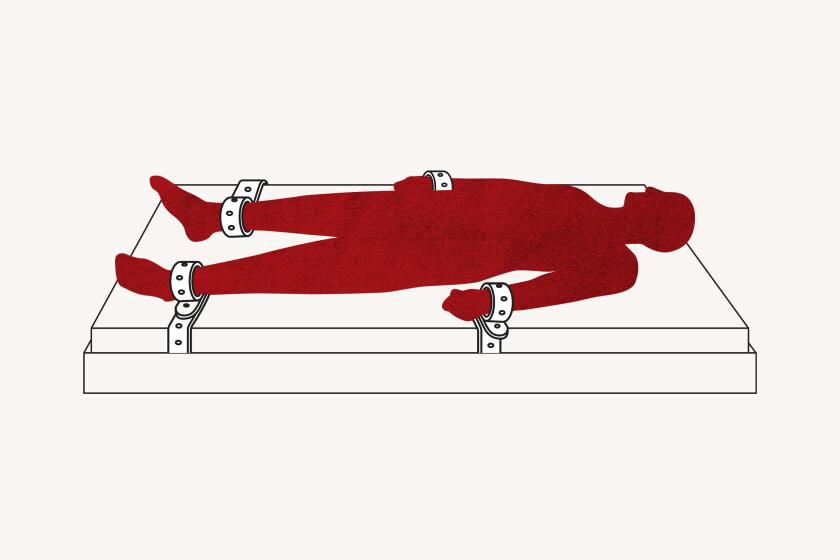

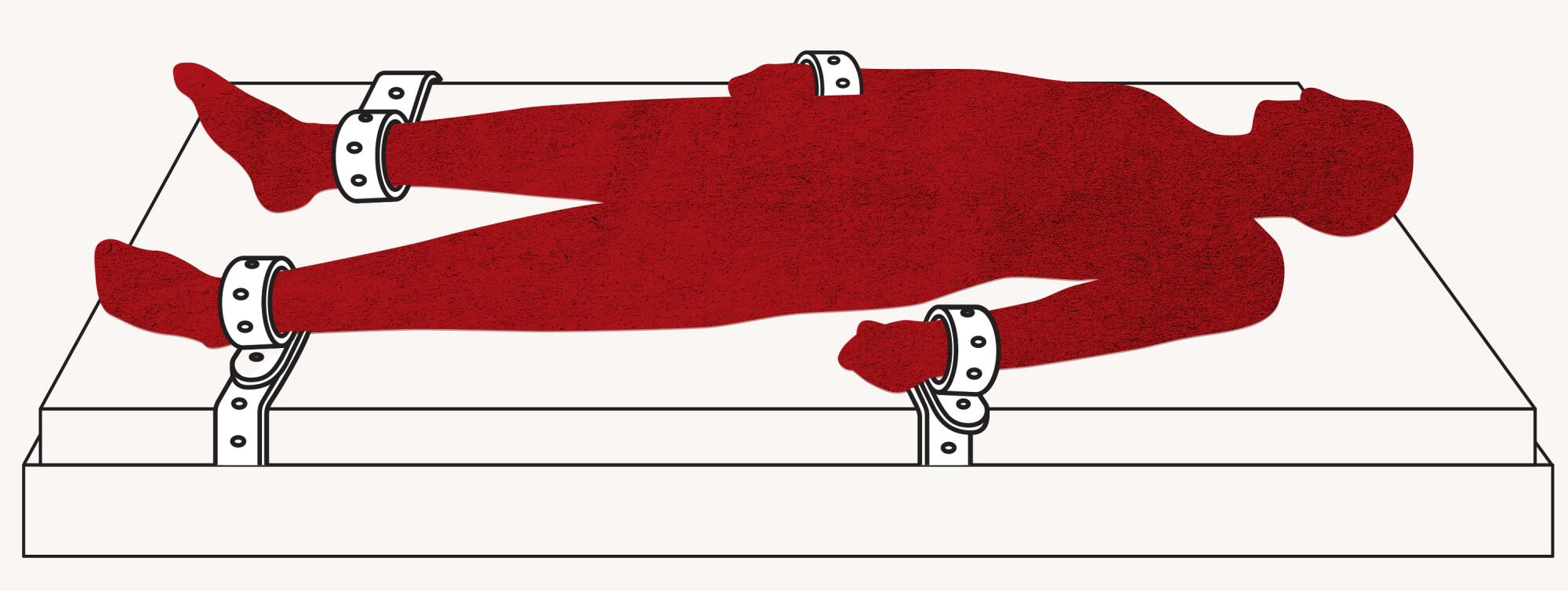

His ankles and wrists bore scars — the result, he said, of repeatedly being strapped to a bed with restraints at Los Angeles General Medical Center.

“I have nightmares I’m being restrained,” said Laidler, who has schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. “That hospital is like one bad dream after another.”

Hospitals are forbidden under federal law from restraining psychiatric patients except to prevent them from harming themselves or others. Restraints can be used only when other steps have failed and are widely discouraged by psychiatric professionals, seen as a measure of last resort that frays trust and can traumatize patients.

At L.A. General — a public hospital serving some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the nation’s most populous county — the psychiatric inpatient unit has restrained patients at a higher rate than in any other in California, a Times analysis has found.

- Share via

Marcelus Laidler was strapped down for at least 300 hours at L.A. General — a public hospital serving some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the nation’s most populous county.

Federal records show that over a recent four-year period, L.A. General’s Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center has reported a restraint rate more than 50 times higher than the national average for inpatient psychiatric facilities, ranking it among the highest in the country.

Those numbers doubled between 2020 and 2021 — the latest figures publicly available — even as the statewide average for other inpatient facilities barely increased.

L.A. General staff have reported 200 cases in which psychiatric inpatients were restrained for a total of 24 hours or more within a month, records dating from 2018 show. Nearly 40 of them were restrained for the equivalent of one week or more, including a woman who spent an entire month in restraints.

Patients are always restrained when transported between the Hawkins psychiatric unit in South L.A. and the hospital’s main Boyle Heights campus, a drive of more than 15 miles, according to county officials. Hundreds of such trips happen each year. County health officials said the restraints are necessary to prevent patients from jumping out of moving vehicles or assaulting staff.

Some psychiatric care experts decried the blanket practice for not distinguishing between patients who might be dangerous and those who aren’t. Even accounting for those transit hours, the restraint rate at L.A. General far exceeded the national average in recent years.

L.A. General officials said they turn to restraints as a “last resort intervention” for combative patients in the face of roughly two dozen physical assaults annually on Hawkins staff. A handful of extremely violent patients has inflated its restraint rate, hospital officials said.

L.A. County officials said that the hospital has received more patients with violent criminal histories in recent years and that Hawkins has “become a sort of pseudo psychiatric jail ward.” Exacerbating the problem, they argued, are long waits for patients who should be transferred to state hospitals or other facilities for longer-term care but instead remain at L.A. General.

“We have not been prepared to handle people at this level of violence,” said Dr. Brad Spellberg, L.A. General’s chief medical officer. He added: “This is about a population of people who have a preexisting history of repeated felony-level assaults who are overtly telling you, ‘I’m going to kill you.’”

When hospital leaders have asked doctors and nurses about trying to reduce the use of restraints, they respond, “You can’t not restrain these folks,” he said.

“If you put these patients in our hospital,” he said, “they end up in restraints.”

Spellberg and other county officials argued that L.A. General cannot be fairly ranked against other hospitals because of its unique challenges as a safety net hospital close to Skid Row and correctional facilities. Private psychiatric facilities are unwilling to take the “difficult” patients that it handles, according to the county Department of Health Services, which operates the hospital.

In reaction to concerns raised by outside experts, Spellberg said, “You come walk a beat in the hospital and take care of the 250-pound person with personality disorder and psychosis who has violently assaulted a dozen people and is telling you they’re going to murder and rape you, and say, ‘Yeah, you don’t need to restrain that person.’”

The county declined a Times request to observe the psychiatric unit, saying it could not accommodate a visit without violating patient privacy. Hospital officials said government regulators had consistently found restraint use at Hawkins to be in line with state and federal rules.

Mental health experts challenged the explanations put forward by Spellberg and other county officials.

“I know those populations and I know how challenging they are,” said Dr. Roderick Shaner, former medical director of the county’s Department of Mental Health, who worked to reduce the use of restraints in psychiatric facilities before his retirement in 2018. “I don’t think that you can say that the ‘nature of the population we are treating ... justifies restraints.’ It justifies the need for sophisticated management of behavior, but restraints are not the go-to thing.”

High rates of restraining psychiatric inpatients do not automatically spur action by regulators, The Times found.

Other large safety net facilities in California and across the country do not use physical restraint at anywhere near the same rates as L.A. General, formerly known as L.A. County-USC Medical Center.

L.A. General psychiatric inpatients were restrained at a rate 10 times higher than at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, according to The Times’ analysis of data from 2018 to 2021, the most recent year available.

Its restraint rate was also far higher than the two other L.A. County-run hospitals with inpatient psychiatric units — 14 times higher than Olive View-UCLA Medical Center and seven times higher than Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

“It doesn’t make sense to me that patients in L.A. are more seriously psychotic and dangerous than patients at a general hospital in San Francisco,” said USC law professor Elyn Saks, who has studied the use of restraints for decades.

Spellberg said the medical facility most similar to L.A. General would be Bellevue hospital in Manhattan, a public safety net facility. The Times analysis found that L.A. General has restrained psychiatric patients at a rate 23 times higher than the New York hospital’s inpatient unit over the same period.

Hospitals restrain patients in a range of ways, some more restrictive than others. Medical staff may strap down their arms and legs to a bed; in other cases they tie the wrists and ankles of a patient so that they can still walk. L.A. General declined to provide the specific manufacturers and models of physical restraints used there, saying that the misuse of such information could threaten safety.

Although hospitals such as L.A. General are required to report how often they use restraints on psychiatric patients, high rates do not automatically trigger action from federal or California hospital oversight agencies, The Times found.

“It doesn’t make sense to me that patients in L.A. are more seriously psychotic and dangerous than patients at a general hospital in San Francisco.”

— Elyn Saks, USC law professor

And the required reporting does not give a full picture of restraint use: The federal restraint data measure only what happens to patients who have been admitted to inpatient psychiatric units, such as Hawkins. When psychiatric patients admitted to other units in the hospital are restrained, those incidents are not included in the federal data.

L.A. County officials are legally restricted from sharing details about specific patients, and hospital records are confidential under federal law.

The Times obtained thousands of pages of medical records for two patients who underwent long periods of restraint in recent years at L.A. General. Both were treated in the same unit outside the hospital’s locked psychiatric ward.

One died days after she had been strapped to a bed, spending 36 hours in restraints in less than a week. Last year, the county settled a lawsuit filed by her mother, who argued that the blood clots that killed her daughter were the consequence of long immobilization due to restraints and medication.

The other patient, Laidler, was restrained for at least 300 hours over the course of five months — in many cases for behavior that experts told The Times did not justify restraint.

When he needs to settle his mind, Laidler, 48, thinks about basketball.

It’s hard for him to remember a time when basketball wasn’t in his life. He loved the sport as a teen growing up in L.A. and dreamed of playing professionally.

Those plans took a turn after the death of his grandmother, which spurred a nervous breakdown that led to his diagnosis with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder at age 16, his mother said. Doctors also detected a brain tumor as big as a baseball, she said, which was removed on Valentine’s Day 1992.

More than two years ago, a psychiatric crisis had landed him at the inpatient ward at Hawkins when another medical issue led him to be transferred to the main campus of L.A. General, according to medical records reviewed by The Times. He was placed in a medical ward for treating patients displaying violent or harmful behavior who are also suffering illness or injury.

Early in his stay, nurses repeatedly noted he was cooperative and compliant with care, medical records show.

But several weeks after his arrival, he grew agitated one night and began shouting at the nurse station, demanding to speak to his doctor “or I will tear up the whole unit,” according to notes in his medical records.

When a doctor arrived hours later, after he had started shouting again, Laidler complained that he was treated like a “second class citizen,” according to the doctor’s notes. He began talking about “his past life as a police officer, a physician, and an airline pilot,” how he had been present at the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, and “how protective he is over his mother.”

“His thought process appeared unorganized and non-linear,” the physician wrote. “He then stated he would ‘kill everyone in the unit’ when he wakes up.”

When psychiatric patients make threats, nurses and doctors must gauge whether those are idle words or indications of an imminent attack, experts said.

The doctor did not indicate that Laidler had attempted to hit anyone. But hospital staff decided to restrain him, strapping down his arms and legs. Medical records said he was agitated, “not following simple directions” and not verbally affirming that he would not hurt himself or others.

Two days later, he was placed in restraints for about 12 hours after he was found shouting in a hallway, arguing with other patients and then calling staff members derogatory names. Once strapped to his bed again, the records say, he continued cursing, shouting, “I don’t care, I will kill you and your mama.”

In another instance, hospital staff wrote he had been restrained after throwing coffee on the floor, causing a staffer to slip and fall. He was “being aggressive with staff” and was unable to assure them he wouldn’t hurt himself or others, staff wrote.

In an interview, Laidler and his mother said he didn’t spill the coffee on purpose, and he didn’t recall threatening to kill people in the unit. He and his mother, Debra Legans, said the medical records did not reflect instances of threats and aggressive behavior from the staff toward him. Legans also felt that medical staff had misinterpreted his behavior, seeing ordinary actions as aggressive or disruptive.

Medical records said Laidler was repeatedly restrained for being “unable to follow instructions, unsafe.”

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

In one episode, a nurse wrote that he was “purposely spilling soda in the hallways” and walking around “intrusive towards other patients and their rooms,” according to medical records. Laidler persisted despite efforts to redirect him, so he was put into restraints, where he remained for 21 hours until he agreed not to threaten staff, a nurse wrote.

In that case and many others, the records show, doctors documented the restraints they ordered as “non-violent,” a designation meant for restraining patients who aren’t being aggressive or self-destructive but might be pulling out their IV lines, breathing tubes or other necessary medical devices.

The distinction is important because state and federal laws require frequent monitoring of patients restrained for violent or self-destructive behavior and limit their use to four hours before an order must be renewed. For other kinds of restraints, hospitals themselves determine how long they can be used before renewal. L.A. County-run hospitals allow “non-violent” restraints to be used for up to 24 hours before renewal.

Laidler’s problems seemed to escalate in early September 2021, four months into his stay on the main campus. Medical records show he was expecting to go home at that time, but he was not discharged for another month.

Legans said she decided her son wasn’t stable enough to leave, concerned he was not yet on the right medications. His anger was unfamiliar, she said — a change she attributed to his treatment at L.A. General.

“They ignited something in him,” she said, making him like “a person I’ve never even seen before.”

After Laidler realized he would remain in the hospital, he grew agitated, according to medical records. That evening, he spat at a respiratory therapist and pushed a nursing attendant who was stopping him from entering the room of a female patient, nurses wrote in his medical records.

“I’ll fight you cuh. I don’t give a f–. Call the sheriffs,” he said, according to their notes. His hands and feet were strapped to his bed, where he remained for more than nine hours.

Medical records show that during his roughly five months in the hospital unit, Laidler was restrained at least 50 times. More than half of those incidents occurred after he was told he was not going home in September 2021.

Hospital staffers wrote that in more than a dozen instances, he had attacked people, thrown things at them or attempted to do either — almost all of those episodes in the tumultuous last month of his stay at L.A. General. Before then, he had been restrained more than 20 times without having struck anyone or attempting to do so, according to medical records.

Joan Gillece, director of the Center for Innovation in Health Policy and Practice at the National Assn. of State Mental Health Program Directors, said a patient is supposed to be restrained only when there is imminent danger to the patient or others. Spilling things or failing to follow directions, she said, “I don’t think meets that criteria.”

Nor do verbal threats, she said. Gillece, who reviewed Laidler’s medical records at the request of The Times, said the documents indicated that hospital staff had attempted some alternatives, such as “comfort measures” and “verbal redirection,” but left it unclear how they were helping Laidler regulate himself.

Restraint is “probably the worst thing that can happen” — and not just for the person who is restrained, Gillece said. For staff, “how do you jump back into a therapeutic alliance with that person when you’ve just tied them down?”

If you want to learn more about how regularly a local hospital uses restraint on psychiatric patients, and how those restraint rates compare with state and national averages, here’s where to look.

Juliano Innocenti, a San Francisco psychiatric nurse practitioner who also reviewed the records, said, “We do not tie people to a bed in psych because they are unable to follow instructions. If that were the case, the majority of an inpatient psych unit would be restrained.”

Laidler and his mother sued the county last year, alleging the hospital mistreated him and used physical restraint “as a means of coercion, discipline, staff convenience, or staff retaliation,” causing him to suffer injuries.

L.A. General said it could not comment on specific patients due to privacy laws. The county has sought to strike parts of the lawsuit and argued the complaint “contains deficiencies that are lethal to a number of his causes of action.”

After Laidler’s mother complained to the California Department of Public Health, the state agency conducted an investigation. A state record summarizing the findings said the agency partially substantiated allegations in the complaint but found no violation of state regulations. The document did not elaborate on what allegations were substantiated.

“That’s not what a hospital is there for — to tear you apart.”

— Marcelus Laidler

However, the record said state investigators found a violation unrelated to the initial complaint. The hospital, they determined, failed to ensure “respectful care” when a nurse used his hand to cover the mouth of a patient who was spitting while they were being physically restrained. The patient is not identified in the document, but details about their care match Laidler’s. The document said the nurse “was released from temporary employment” at the hospital.

The state agency did not answer questions about the scope of its investigation and whether it had examined more than one episode of restraint.

Laidler said he spent many hours in the unit strapped to the bed, unable to clean himself. His mother said she was alarmed to find that the clothes she brought for him were often soiled with feces and urine when she put them in the laundry.

“I was sitting in my own poop, going out of my mind and thinking, how did this happen to me?” he said.

Medical records show that his mother, his court-appointed conservator, repeatedly raised concerns about the use of restraints, at one point telling a nurse “her son is being treated as an animal.”

The restraints were often so tight he was left with bloody sores where the straps rubbed his skin, he and his mother said. His medical records state he had developed irritated skin and swelling due to restraints, which had been managed with topical medication and creams.

For Laidler, two years after being discharged from L.A. General, the nightmares haven’t gone away. Sometimes he sees a commercial on television for a hospital — any hospital — and the memories rush back. He tries to think “happy thoughts” of basketball to cope.

“That’s not what a hospital is there for,” he said, “to tear you apart.”

Los Angeles General occupies a sprawling campus east of downtown L.A., close to an area that lays bare some of the region’s most intractable social crises.

About a mile from the main campus is the county’s jail complex, which houses thousands of people who are mentally ill. Two miles away is Skid Row, where homelessness, violence, mental illness and drug addiction are pervasive.

As a public safety net hospital, L.A. General said it accepts many especially challenging psychiatric patients whom private medical centers typically won’t admit.

People feared to be a danger to themselves or others are brought to the psychiatric emergency department in Boyle Heights, sometimes by police. Some are later admitted as inpatients to L.A. General’s Hawkins Mental Health Center, which houses a 60-bed locked psychiatric unit.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

All Hawkins patients transported between the main L.A. General campus and the locked psychiatric unit in Willowbrook are put into restraints, according to county health officials.

The Hawkins psychiatric facility was initially created as part of King/Drew Medical Center, a nearby county hospital, then became part of L.A. General as King/Drew was scaled back and ultimately closed. No other hospital psychiatric unit in the county is physically separated from its main medical facility, county officials said.

“Transportation provides an opportunity for elopement and unpredictable behavior in a less controlled environment,” the county said in a statement. “During transportation of patients, every effort is made to ensure that an equivalent, secure environment, similar to that of the locked hospital setting, is replicated.”

County officials estimated that in 2020, patients spent more than 1,400 hours in restraints while being transported from one campus to the other. Some experts criticized the practice, saying it treats all Hawkins patients as if they were a safety risk.

“It’s just not necessary. It’s traumatizing and it certainly doesn’t help gain a person’s trust,” said Kevin Huckshorn, a mental health nurse and national expert on restraint reduction strategies. “A blanket policy ... is not best practice” and is an excessive use of restraint, she said. “Everybody’s not dangerous.”

A county health services department spokesperson said the agency is planning to relocate the inpatient psychiatric ward from Hawkins to the main Boyle Heights campus.

L.A. General officials said they work hard to avoid using restraints and try alternative methods to calm agitated patients.

Dr. Frances Gill, a third-year psychiatry resident at L.A. General, said she felt she had gotten solid training in such de-escalation techniques. She described painstaking work she underwent with one patient at Hawkins who had been chronically restrained due to violent outbursts. As Gill talked with her, “she could report, ‘I’m feeling these urges, I feel like I’m going to hit someone, I feel like I want to hurt somebody,’” Gill said.

Gill helped develop a plan to encourage her to change her behavior, offering things she wanted, such as having food from Panda Express brought to her at Hawkins.

“This was a long process, but it was very rewarding to me to be present on the day where she was like, ‘OK, I’m good, no restraints,’” Gill said. “That’s one of those moments when you’re like, ‘This is why I went into psychiatry.’ These are people with really serious challenges who sometimes just need a lot of patience and a lot of time.”

Reducing the use of restraints “requires larger scale changes than just flipping a switch and not using restraints anymore,” Gill said.

Hawkins is set up for patients who are in a psychiatric crisis to be treated and stabilized after a short stay, but many of its patients have enduring issues that require longer-term care, county officials said. The problem: There are too few places to send them once they are no longer in crisis.

The county estimated four years ago that it needed an additional 3,000 beds for patients in need of longer-term care. In recent years, state hospitals have cut back on admitting patients from L.A. County-run hospitals who have been found by civil courts to be a danger to themselves or others, county officials said, leaving patients with serious mental illnesses stuck in county hospital inpatient wards for months or longer.

The Department of State Hospitals, in turn, said new admissions of such patients hinge on counties helping to discharge others at the state hospitals who are ready to return to the community. As of May, there were dozens of L.A. County patients awaiting discharge from state hospitals, the state agency said.

Some patients have been at Hawkins for more than two years while they await transfer to state-operated facilities. Enduring such delays “actually increases the level of agitation,” said Solomon Ayen, a supervising staff nurse at Hawkins.

One patient who waited 17 months in vain to get back to a state hospital assaulted eight other patients, a maintenance worker and seven other staffers, the county said in a statement.

That patient was among a small number of outliers who account for a large share of the restraints used at the hospital, county health officials said.

County officials said that just five patients accounted for 67% of all restraint hours at Hawkins in 2020. The following year, they said, seven of the 10 most frequently restrained patients had also been in the top 10 the previous year. The Times could not confirm the county’s numbers: Restraint data reported to federal authorities and released to the public do not identify who is restrained and for how long.

Some attacks on staff members have resulted in traumatic brain injuries and other injuries requiring medical leave, county officials said. One patient, they said, repeatedly assaulted another patient who was disabled and attacked staff, including with their own blood, urine and feces.

The Times analyzed restraint data for psychiatric inpatient facilities that have been collected by the federal government since 2013.

Hospital officials said that “the level of acuity and violence experienced among our inpatients has increased dramatically in the last five years,” and that “assaults [on staff] have risen dramatically resulting in serious injuries.”

The county later provided figures indicating that the average number of attacks at Hawkins each month fell from more than four in mid-2018 to two in 2019 — and remained around the same levels through April 2022.

Still, the problem has alarmed hospital staff, who have ramped up the presence of security at Hawkins and launched initiatives meant to reduce physical attacks by patients in the psychiatric emergency room and other hospital wards. California workplace safety regulators cited the hospital four years ago after two incidents in which a psychiatric patient at Hawkins injured staff.

But mental health experts said that forcing patients into restraints can also be dangerous for nurses and aides. One study at a youth facility in Massachusetts found that after an initiative to reduce the use of restraints, staff injuries decreased in severity.

When workers put people into restraint, “when we lay hands on them, that’s actually the highest risk time for us as staff members to be injured or assaulted,” said Dr. Mark Leary, deputy chief of psychiatry at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

In the face of its challenges, L.A. General should be developing a treatment strategy that makes restraint less necessary, said Kim Masters, a psychiatrist and affiliate assistant professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, who has studied restraint for decades. Restraining people for long periods can harm them and make them less receptive to treatment, he said.

“All you’re doing with these patients is making them more violent and more aggressive,” Masters said. “Then they go out and become more violent and more dangerous than they were when they came in.”

Many experts also emphasized the need for hospitals to use a range of tools, such as weighted blankets or music, to calm patients before they lose control.

L.A. General officials said they were using strategies advocated by national experts on reducing restraints. The hospital, they said, has areas that serve as comfort rooms and employs peer support specialists.

But a hospital official identified the areas in which patients can calm down as “seclusion rooms,” the same spaces where patients are restrained, according to the county. Experts said using the same rooms for restraint as for comfort could undermine their appeal as a relaxation space.

To control the spread of COVID-19 at the height of the pandemic, L.A. General halted group occupational and recreational therapy, which can include music, arts and crafts, sports and calming tools such as weighted blankets or lavender oils. Individualized treatments were also limited.

County officials said the move probably contributed to its higher rate of restraint in 2021. Other safety net hospitals told The Times they did not stop such therapy groups during the pandemic. “We have no information to suggest infection control measures led to more use of restraints,” said a spokesperson for Zuckerberg San Francisco General.

In recent years, L.A. General has had a restraint reduction plan that says it is exploring ways to “prevent, reduce and strive to eliminate restraint” use. The one-page document listed nine general ways that the hospital would pursue that goal, including by collecting data to monitor restraint use.

Despite the plan, its restraint rate at Hawkins has remained the highest in the state and has grown higher in recent years.

Stella Summers was a teenager who loved basketball and singing, who thought she might someday work as a caregiver for the elderly, her mother said.

She had been in and out of hospitals after troubling signs of her mental illness emerged, medical and court records show. She said she was hearing voices. She once brought a dying bird to school. She hacked off her hair, leaving a glaring bald spot.

At a Westside residential treatment center, she attacked another resident and was taken to L.A. General, where she was admitted in September 2018, according to medical records filed in court. She believed that evil spirits were pouring out of the resident she hit, a psychiatrist wrote.

Under a psychiatric hold, Summers was initially supposed to remain for 72 hours to be stabilized. It was the kind of stay Summers had undergone at other hospitals many times before, her mother said.

Two weeks later, the 19-year-old was dead.

In the previous nine days, Summers had been restrained twice by medical staff, spending a total of 36 hours in restraints, the medical records show.

During her stay, hospital staffers said Summers struck an employee, prompting them to secure her wrists and ankles to her bed. Four hours later, a doctor issued a new order to continue restraining her, indicating she was “unable to follow instructions, unsafe.” Later that morning, a nurse reported that Summers remained “unpredictable, verbally aggressive and unable to follow commands.”

She was held in restraints for 13 hours, according to the medical records. She was then transferred to the same unit for patients with behavioral problems where Laidler was later hospitalized.

A few days later, the teen was restrained again, this time for 23 hours, after hitting a nursing assistant in the head, medical records show. For much of the day, she spat at or tried to grab or hit staff members, the records indicate.

But Summers continued to be restrained long after she seemed to have regained control of herself the following morning, according to a psychiatric nurse retained as an expert by her mother, Chrysie Anagnostou.

Anagnostou also raised concerns about the dosage of medications that she said left her daughter unable to speak, telling medical staff: “My baby got worse. She needs to survive this,” according to medical records.

On Oct. 4, 2018, three days after she had been released from restraints, Summers fell and hit the back of her head while walking backward, medical records show. She began to suffer shortness of breath and was given oxygen.Hospital staff did chest compressions and shocked her heart to try to save her.

The county medical examiner’s office determined her death was caused by blood clots in her lungs related to a condition known as deep vein thrombosis in which a blood clot develops, typically in the legs.

Obesity is one risk factor. At the time she was hospitalized, Summers was more than 6 feet tall and weighed over 300 pounds; her mother said her medications had caused her to gain weight.

Other risk factors include immobilization. One study by Japanese researchers found that psychiatric patients restrained for longer periods developed deep vein thrombosis at higher rates.

In her lawsuit against the county, Summers’ mother argued that her daughter was overmedicated at the hospital and subjected to “excessive use of bed restraints” without effective treatment to prevent the blood clots that killed her.

Experts retained by L.A. County said Summers’ violent behavior left hospital staff with no alternative but to restrain her and that they took appropriate steps to prevent blood clots, but one acknowledged that a “brief immobility of less than 48 hours” was a risk factor for deep vein thrombosis.

In December, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors agreed to settle the lawsuit for $600,000.

Inside her Hawthorne home, Anagnostou and her son, Christopher Summers, showed off old photographs of Stella. One framed image was smudged with brownish lipstick, from the daily kisses of her mother.

In the mornings, Anagnostou lights a memorial flame in the Greek Orthodox tradition in front of an image of her daughter, “to give her the light of Christ.”

“My daughter walked in the hospital,” Anagnostou said, tearfully. “She was supposed to walk out.”

More to Read

About this story

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.