- Share via

When the city started to burn, James An’s mother was driving her new BMW in South L.A.

An was 12 years old, but he knew the luxury car — and her Korean face — could make her a target. He called her car phone and urged her to “get the hell out.”

On the radio, he heard business owners pleading for police protection as their livelihoods vanished in front of their eyes.

On television, he saw much of Koreatown on fire, including an electronics store he loved, half a mile from his family’s Korean-Chinese restaurant.

His father soon left their Glendale house, gun in hand, to defend the restaurant. “Protect your family,” he told the boy.

“I remember thinking, what the hell am I going to do? I’m 12 years old,” An recalled. “How am I going to [respond], if people come to my house with guns?”

The restaurant was spared. But many of An’s favorite Koreatown haunts were in ruins: a CD warehouse, a Kinney shoe store, an ethnic grocery store with signs in English, Spanish, Korean and Japanese.

For 30 years, An has tried to understand what happened after the police officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted on April 29, 1992, setting off days of looting and destruction.

As president of the Korean American Federation of Los Angeles, he is in regular touch with politicians and community leaders of many backgrounds.

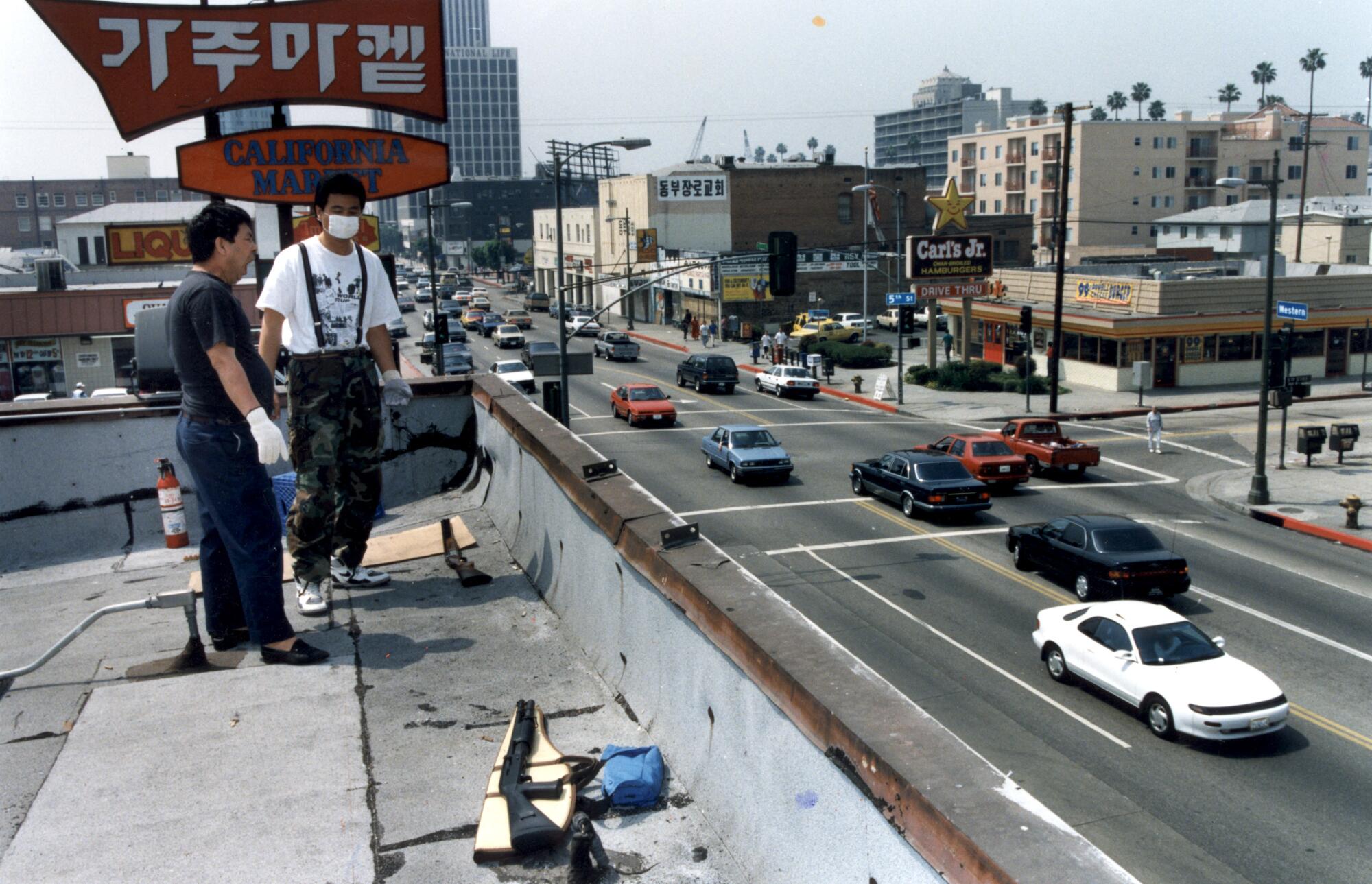

The days of armed Koreans on rooftops defending their businesses from rioters, with the LAPD nowhere in sight, sometimes seem a distant memory.

It’s a town where people don’t meet your gaze, first names are taboo, and piles of shoes greet you at the doorway.

Black-Korean relations, once symbolized by the fatal shooting of Latasha Harlins by a Korean liquor store owner, have improved one interaction at a time, from the shopkeeper who smiles and offers warm greetings to leaders like An working to build cross-racial ties.

Latinos, who are 51% of Koreatown’s population, have successfully lobbied for a sign marking the “El Salvador Corridor.” They have teamed with Koreans on workers’ rights campaigns and school issues.

But An, 42, wonders what fissures still exist underneath.

“I haven’t been able to figure that out,” he said.

After the riots, called Saigu — 4/29 — in Korean, some business owners returned to South Korea, their immigrant dreams shattered. Others were unable to get government relief or insurance reimbursements. Some were too traumatized to keep working.

Seven thousand miles from California, today’s fifth-anniversary observance of the Los Angeles riots still is an occasion for agonizing reflection by thousands of Koreans who experienced 1992’s unrest firsthand and returned to South Korea deeply scarred.

Yet, as the years passed, many Korean Americans rebuilt their businesses or started new ones. Wealthy South Koreans poured money into the neighborhood. Korean pop culture exploded globally.

At Hannam Supermarket on Olympic Boulevard, where Koreans with guns crouched behind cars in 1992, K-pop stars filmed a music video several years ago.

On the rooftop of California Market, where armed Koreans once patrolled, hipsters snack on spicy rice cakes and Korean corn dogs.

Korean Americans gradually built enough political clout to place all of Koreatown in a single city council district. A community that once felt abandoned by the police recently rallied to make sure that the LAPD’s Olympic station stayed open.

The mention of the possible closure of Olympic station, amidst city budget cuts, sent Korean American leaders to the LAPD’s defense and rallying to keep a strong police presence in their community.

But 30 years later, everyone who experienced Saigu is scarred in some way, whether it is the unending grief of Jung Hui Lee, whose son was the only Korean American killed in the riots, or the questions still asked by a man who as a teenager saw the stores of fellow church members burned down.

“What did we do, or what did those church members do so wrong that caused this much retaliation?” said Joshua Song, 47, vice president of a company that helps businesses bridge the divide between Asia and North America. “If I try to rethink those events, there is still no resolution. Maybe that’s why it’s so traumatic.”

In some spots, the rebuilding began quickly.

At 6th Street and Vermont Avenue, a strip mall that had gone up in flames was soon rising again.

Laura Park told the owner that she was interested in moving her Korean dress shop there.

LeeHwa Wedding and Korean Traditional Dress has been there ever since and is now one of the longest-operating Koreatown businesses, surviving the 1994 Northridge earthquake, several economic downturns and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Koreatown was once the place one left. Now, focused on a shiny strip of Wilshire, it’s a mecca for suburbanites and wealthy immigrants.

Park, 58, also lives in Koreatown and has seen the neighborhood change, with new condos towering seven stories or more. She likes the convenience of shops, restaurants and friends close by.

“The place that burned down is the place that flourishes,” she said.

In 1992, as a photographer for KoreAm Journal, T.C. Kim shot images of that same strip mall burning.

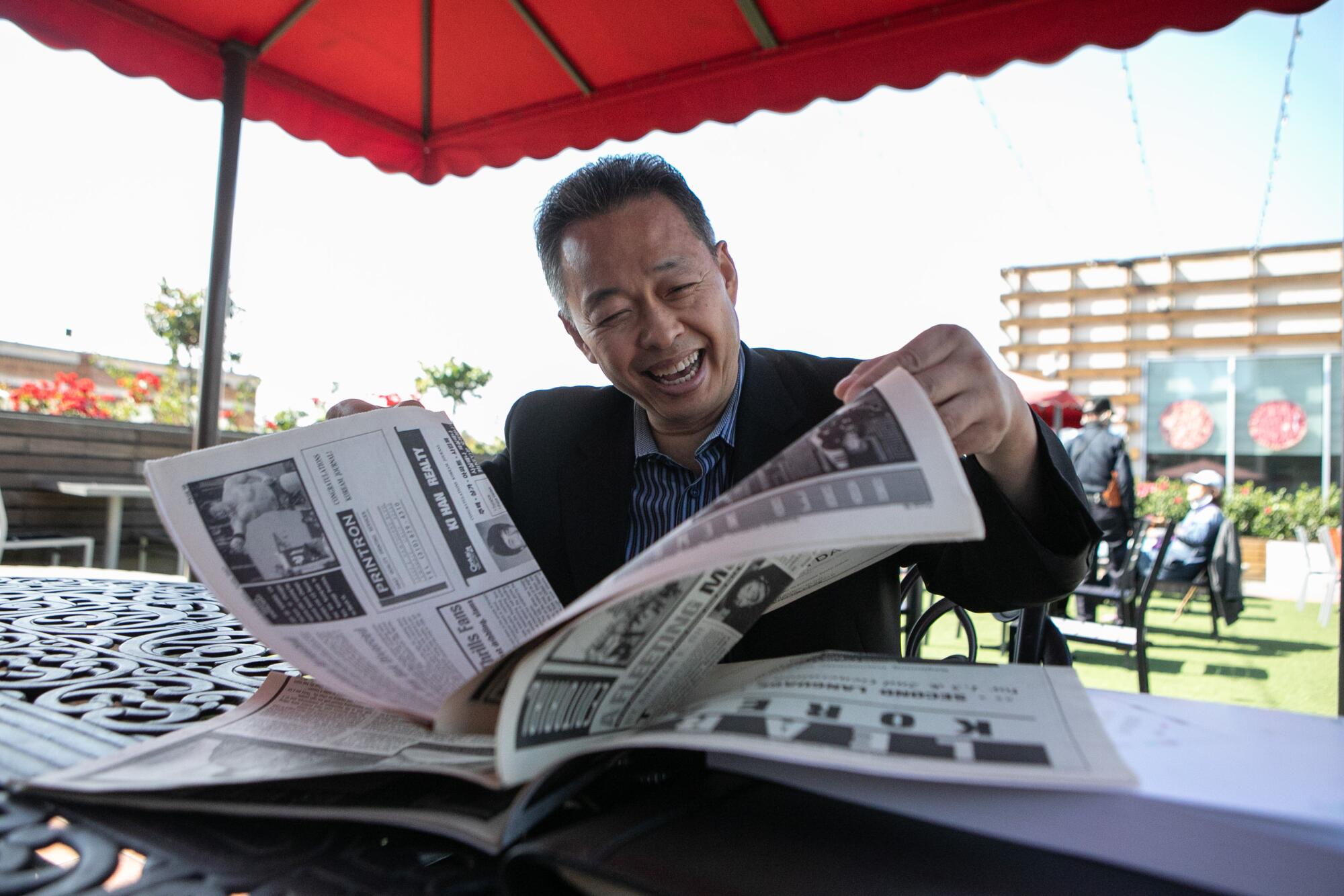

Soon after, he left for the suburbs, raising his kids in Glendale. Koreatown just didn’t feel safe, he said recently from a picnic table on California Market’s rooftop patio.

Two years ago, after his youngest son graduated high school, Kim moved back to Koreatown.

A longtime community leader and consultant for nonprofits, he loves living in a neighborhood where many restaurants and bars are open past 10 p.m. He thinks the riots were a turning point for Koreatown.

“Now, we see the value in getting involved in politics, increasing our voice, and there’s a value in being concerned about what happens in other communities,” he said.

For Latino residents, many of whom are of Central American descent, the very name “Koreatown” has made them feel invisible, even though they have long outnumbered Asians.

Raul Claros was 11 in 1992 when the rioting hit Koreatown.

From his family’s apartment on South Ardmore Avenue near Olympic, he saw billowing black smoke, heard crashing glass and smelled burning fuel.

Friends and neighbors rushed to join in the chaos, including his best friends from across the street.

Many returned home with looted sofas, groceries and electronics, Claros recalled. Others in the mostly Latino apartment complex stayed put.

“I wanted to go, but I was too afraid my mom would whoop my ass,” Claros said. “I just wanted to be with my friends, who were angry. We were all angry.”

Latinos in Koreatown felt forgotten, Claros said. Many apartments were owned by slumlords, and some Korean store owners treated Latinos as if they were all thieves, he said.

His principal at Hobart Boulevard Elementary School asked him whether he had participated in the looting.

Claros, who is of Salvadoran and Costa Rican descent, became an aide to politicians, including L.A. Council Member Herb Wesson, and co-founded the Reimagine LA Foundation.

He was among the local Central American activists who fought for the El Salvador Corridor designation and street sign, a block south of Olympic on the border with Pico-Union, which was approved by the city in 2012.

Relations between Koreans and Latinos improved after the riots, according to Claros.

In one example of cooperation, the Koreatown Youth and Community Center has built a PTA-like network of more than 200 Latina mothers.

But as housing prices skyrocket throughout the region, Koreatown is becoming unaffordable for some longtime residents. Senior citizens can wait more than a decade for a unit in an affordable housing complex.

The neighborhood’s booming dining scene and nightlife have lured young professionals while pricing out others, both Korean and Latino. Some businesses can’t compete with hipper, newer spots.

If mom-and-pop eateries serving galbijim, kimchi jjigae or soondubu are replaced by trendy fusion places and chains, will Koreatown lose its soul?

Blanca Lopez, 63, has sold pupusas from her mobile kitchen along Olympic, Wilshire and other Koreatown thoroughfares for 18 years.

But she doesn’t know if she can afford to keep working in the area. The rent for her home in nearby Pico-Union has gone up by $500 over the last five years. She is thinking of moving to Sylmar.

“I know many more people who left than have stayed,” she said.

In his work with the Korean American Federation, An often helps with housing issues.

On a recent Monday morning, he was trying to find a home for an 83-year-old man sitting in the LAPD’s Olympic station who had ended up there after domestic violence issues with his daughter.

For nine months, An had also been looking for housing for an 84-year-old Korean woman whose mental health was rapidly deteriorating.

When he hears his phone ring, Seon Jin Kim’s whole body flinches and his ears perk up.

As he builds relationships within the Korean community and outside it, An draws on the struggles of his parents, who came to the U.S. with $800 in their pockets, started their own business and then saw their neighborhood burn down in civil unrest.

At the American diner in Koreatown he owned until 2018, An helped a new immigrant from Mexico rise to be an exemplary waiter and then a manager at the El Torito chain.

Latino and Black residents often come to get pandemic assistance from An’s Korean American Federation.

Elsewhere in the neighborhood, Simon Joo and Mayra Gutierrez have struck up a friendship through the Koreatown Run Club, which organizes group jogs.

They grew up distant from each other — he in Seoul and the U.S., she in Koreatown — but both were fans of the K-pop band H.O.T.

Gutierrez, 36, who is Salvadoran American, feels deeply connected to both Korean culture and her family’s culture.

“Koreatown is home. It’s always going to be home,” she said. “Korean culture is ingrained into my entire being, but the culture that I’m actually from is also here. So, for me, there is no place like it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.