Column: What we got wrong about Black and Korean communities after the L.A. riots

- Share via

“What are you doing down here?”

The year was 2017, and I was at the intersection of Manchester and South Normandie avenues, where the Los Angeles riots had raged a quarter century before. I was explaining to a local pastor that I was a reporter at the Los Angeles Times doing a story on a restaurant chain.

I’m a journalist, I responded, here to write a story for the newspaper.

“Yeah, I heard you. But what are you doing down here?” he repeated, a little more loudly this time. “Aren’t you scared? You people don’t usually come down here.”

His tone was brusque but not hostile. We kept talking, and it became clear he wasn’t referring just to the L.A. Times but to the fact that I am Asian American. He relaxed visibly when I explained that I am not Korean.

I did not experience the Los Angeles riots, but I have covered race and ethnicity for this paper for a decade. With a face that many mistake for Korean, I have come to know the aftermath.

The Black-Korean conflict was an enduring storyline during the violence that erupted in 1992 after four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King. It was a palatable narrative of racial conflict in which white racism was not directly implicated.

It was a politically convenient story for the Los Angeles Police Department, which was glad to see headlines dominated by stories of racial conflict in which the police were not at fault. And the narrative’s consequences live on — not just in neighborhoods like South L.A. but in the ways that Black and Asian American people think of themselves.

In parts of Koreatown and South L.A., each block tells different stories about the riots. Each old building is a testament to survival and community; every empty lot, a eulogy.

To me, the story of the L.A. riots is the tale of two videotapes: one a blurry camcorder recording of King’s beating; the other, closed-circuit footage of Latasha Harlins’ murder in crisp black and white.

Latinos played a bigger role in the riots than we care to remember. Latinos were killers and the killed, assaulters and assaulted, looters and looted.

Historians might argue about whether the LAPD and its chief at the time, Daryl Gates, were racist. But they have little ambiguity when it comes to liquor-store owner Soon Ja Du, who accused Latasha, 15, of shoplifting and shot her in the back of the head. Latasha had put a bottle of juice in her backpack and had $2 in her hand.

Because Korean Americans lacked representation in the mainstream media, Korean American shopkeepers became the victims and villains of the riots, racism’s symbols and scapegoats.

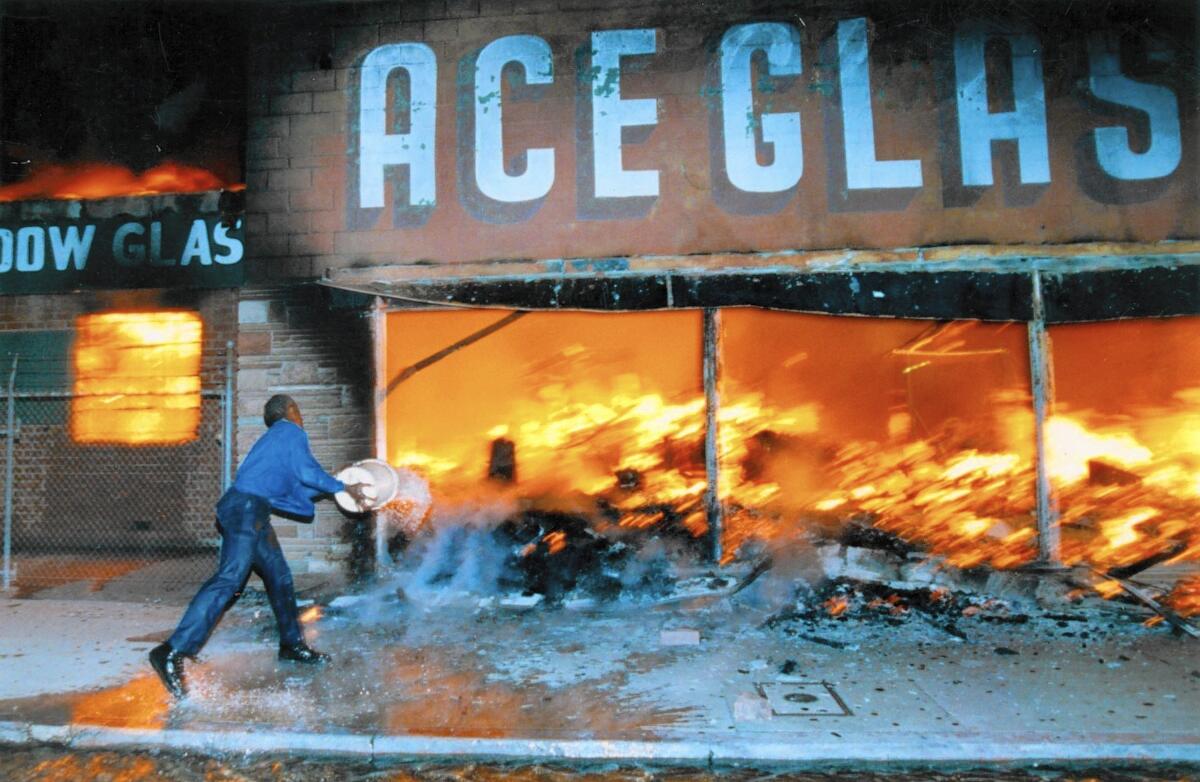

About 45% of all properties damaged were Korean-owned, according to the Korean American Grassroots Conference. Scores of Korean American shopkeepers were murdered, robbed and beaten in the years before and after the riots, including 25 who were shot and killed between January 1990 and May 1992, according to the Koreatown Emergency Relief Committee. A rash of depression and suicides left mental scars on the wider Korean American community that would last generations.

The Black-Korean conflict described a very real nationwide dynamic between Korean shopkeepers and their largely Black customer base that was marked by violence, boycotts and protest.

Korean shopkeepers, terrified by violence and crime, did not treat their Black customers with the respect they deserved. Black communities — frustrated by not just their treatment but by economic racism and disinvestment — organized boycotts of Korean-owned stores that would not hire Black people.

But “Black-Korean conflict” was also a term that confined the discussion of the riots’ racial conflicts to those two communities — “players in a zero-sum game,” as John H. Lee, then a reporter for the L.A. Times, described it.

“How that term that was being applied to those specific shooting incidents and how it extended to Koreans and blacks as people, as a population — it did not make sense to me,” Lee said.

This past week, I had lunch with two reporters from the Korea Times, and we discussed the Black-Korean conflict.

Peter Pak was 32 when the King verdict came down. He was an on-camera reporter who went live from the First African Methodist Episcopal church the day the violence broke out. He still feels persecuted by the narratives perpetuated around the Black-Korean conflict.

“Why does mainstream media make a frame like that? What is the agenda?” Pak asked me.

It was a genuine question, and one that I had trouble answering.

Were the news media dominated by white perspectives and readers eager for stories about racial conflict in which white racism was not the villain? Were Korean Americans used as a convenient political tool for those who wanted to reject Black demands for racial justice?

With her astounding decision that the killing of Latasha Harlins warranted not a single day of jail, Judge Joyce A.

Whatever the motivation, the timing of Latasha’s killing was highly beneficial for the embattled LAPD. Judge Joyce Karlin’s decision not to sentence Du to prison time was upheld just one week before the King verdict.

History always reflects the worldview and aspirations of those who are writing it. Over the years, I have collected the stories of the buildings that remained standing after the riots ended because Asians, Blacks and Latinos were able to find common cause: a Chinese eatery on Virgil, a Cambodian jewelry shop in Long Beach, a Thai restaurant in Koreatown.

In the story I wrote about the Cambodian-owned fried chicken chain in South L.A., I focused on the smiles I saw, not the bulletproof glass.

Did I treasure these stories because Asian Americans were not the villains?

Our remembrances of the riots are shaped by these desires. Every anniversary, the same photos, videoclips and storylines are revisited in an attempt to make sense of what happened.

Newer generations of Angelenos like myself learn about the riots through these remembrances, but the story we learn is no more conclusive than it was in 1992.

And I’ve noticed that conversations about the L.A. riots often end up as arguments about the American dream. Korean immigrants left their homeland trying to achieve it, and many lost their belief in it after the riots. But was the American dream ever real if Black people never had equal access to it?

We Asian Americans are always used as evidence that it is reachable for all. Because some of us can achieve educational and financial success, racism is disproved. Our success is used to confirm the belief that this country is a meritocracy.

But I think the truth is more complicated than that — a three-dimensional object that will always look different based on where you stand. We see more of the truth when we can shift our perspective. Two voices can speak equally loudly and eloquently at the same time, but if they don’t talk to each other, all we hear is chaos.

Each anniversary, I’m struck by the fact that there is no public memorial or space dedicated to the memory of the riots, though last year, artist Victoria Cassinova painted a mural of Latasha at a South-Central recreational facility.

Read our full coverage of the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots.

Perhaps that absence reflects the fact that we don’t all agree on how to remember it.

Today, Korean Americans still own swap meets and beauty supply stores that primarily serve impoverished Black and Latino communities.

At liquor stores, a new generation of economically disenfranchised Southeast Asian and South Asian immigrants is behind the counter.

Black communities still suffer from police brutality and economic racism.

And just last month, I wrote about Yongja Lee, a Korean liquor-store owner who was stabbed by a Black suspect.

But 30 years have passed since the riots, said Ellyn Lee, Yongja’s daughter. Customers organized a GoFundMe campaign for the liquor store and raised nearly $10,000. They recalled how Yongja made kimchi jjigae for dinner and shared it with them.

“The community was for us,” Ellyn told me. “Not against us.”

The problem, though, is that stories of harmony receive far less coverage than tales of conflict — today and in 1992.

John H. Lee’s most memorable interview from the riots’ aftermath was with a Korean shopkeeper who decided to stop keeping guns at his shop and cease selling hard liquor in an attempt to bond with his Black customer base.

Lee had left the L.A. Times and was stringing for the New York Times. The anecdote ended up somewhere in the back end of the story.

Edward Taehan Chang, a UC Riverside professor and member of the Black Korean Alliance that began in 1986, said he remembers getting media coverage twice: when the group began and when it broke up the year after the riots.

“The media tend to focus on racists rather than peaceful resolution,” Chang said. “They weren’t interested in covering our efforts, except when we were dissolving.”

Lee quit the L.A. Times in 1993 and went back to Asian American media, working as an editor for the KoreAm Journal and later the Rafu Shimpo after a brief stint writing for the New York Times. He felt a clearer sense of mission working for ethnic media, he said.

“My goal has been to somehow dispel that notion that there is an intrinsic conflict between Black and Korean people.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.