Column: He was murdered during the L.A. riots. We can’t forget Latinos like him

- Share via

BAKERSFIELD — Thirty years ago, Eduardo Cañedo Vela was the manager at a Japanese restaurant in Bakersfield and hoped to one day open a place of his own.

A Mexican immigrant, he had two small daughters and a son on the way.

For the record:

5:31 p.m. April 28, 2022An earlier version of this column misidentified Aurea Montes-Rodriguez as the vice president at Community Coalition. She’s the executive vice president.

At home in the small Central Valley city of Arvin, he cooked all the meals, helped to change diapers and even combed his little girls’ hair.

“If anyone ever needed something, they’d go to him,” his wife, Rosa Bañuelos Ortiz, said recently.

That’s what a friend did when he asked Cañedo for a ride to Los Angeles to cash a tax refund on April 29, 1992.

Cañedo, 33, knew nothing about Rodney King. He had no clue that a jury was about to acquit the four Los Angeles police officers who savagely beat King a year earlier, or that simmering racial and economic tensions were going to explode into some of the worst civil unrest in American history.

He figured it might be fun to make a quick trip back to the city where he had once lived.

Bañuelos agreed. Yet something pulled at her just before her husband left. “I suddenly thought,” she said, “that I’d never see him again.”

She asked to accompany him, and he demurred — it was too far for the girls. Besides, he promised to return that night.

Her premonition proved right.

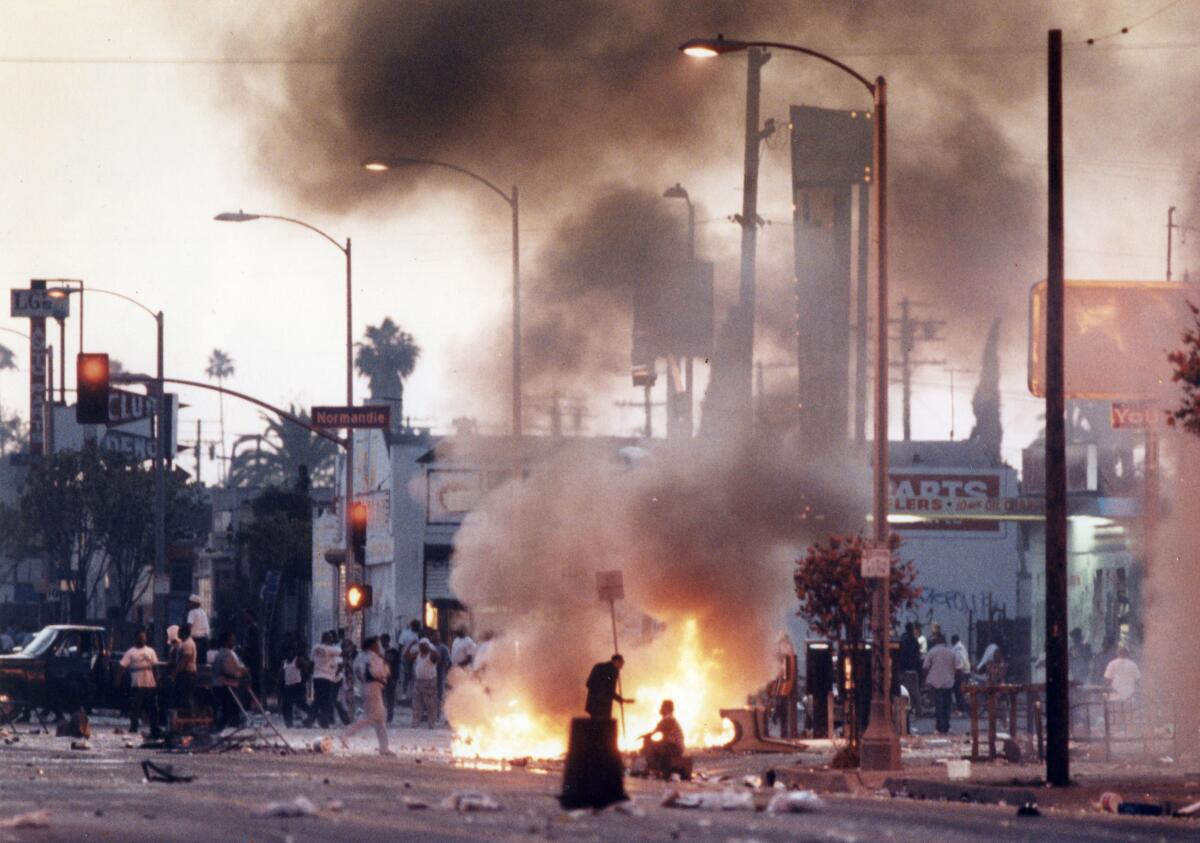

As the violence began to escalate across South L.A., Cañedo was shot dead in his Ford Taurus.

He had been having nightmares about that very thing — being somewhere unfamiliar, a stranger approaching with a gun and pulling the trigger.

“If I had gone,” Bañuelos said quietly as her daughters, now grown, looked on, “none of that would’ve happened.”

She rarely spoke about the murder, even as her kids started asking more questions.

In junior high, her older daughter, Mayra Ortiz, Googled her father’s name.

On website after website, Ortiz found the father she remembered for piggyback rides and walking her to school reduced to a line in the lists of riot murder victims. Even worse, they got his name wrong.

Most publications referred to him as Eduardo Vela, when by Mexican Spanish naming conventions, the surname is in the middle, not the end. When media used his full name, they omitted the tilde in “Cañedo.” (This paper uses Eduardo C. Vela in a database of the dead.)

“He was not just a statistic,” said Ortiz, now 33, who works for the state government. “He was a human who would never fulfill his dreams. He deserves to be more than an incorrect line on the internet.”

As Southern California marks the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots, we should all reflect on Eduardo Cañedo Vela. He is a voice scrubbed from the past, one that offers a warning to us today: Never forget.

Never forget that Latinos played a far bigger role in the riots than we care to remember or admit. Latinos were killers and the killed, assaulters and the assaulted, looters and the looted.

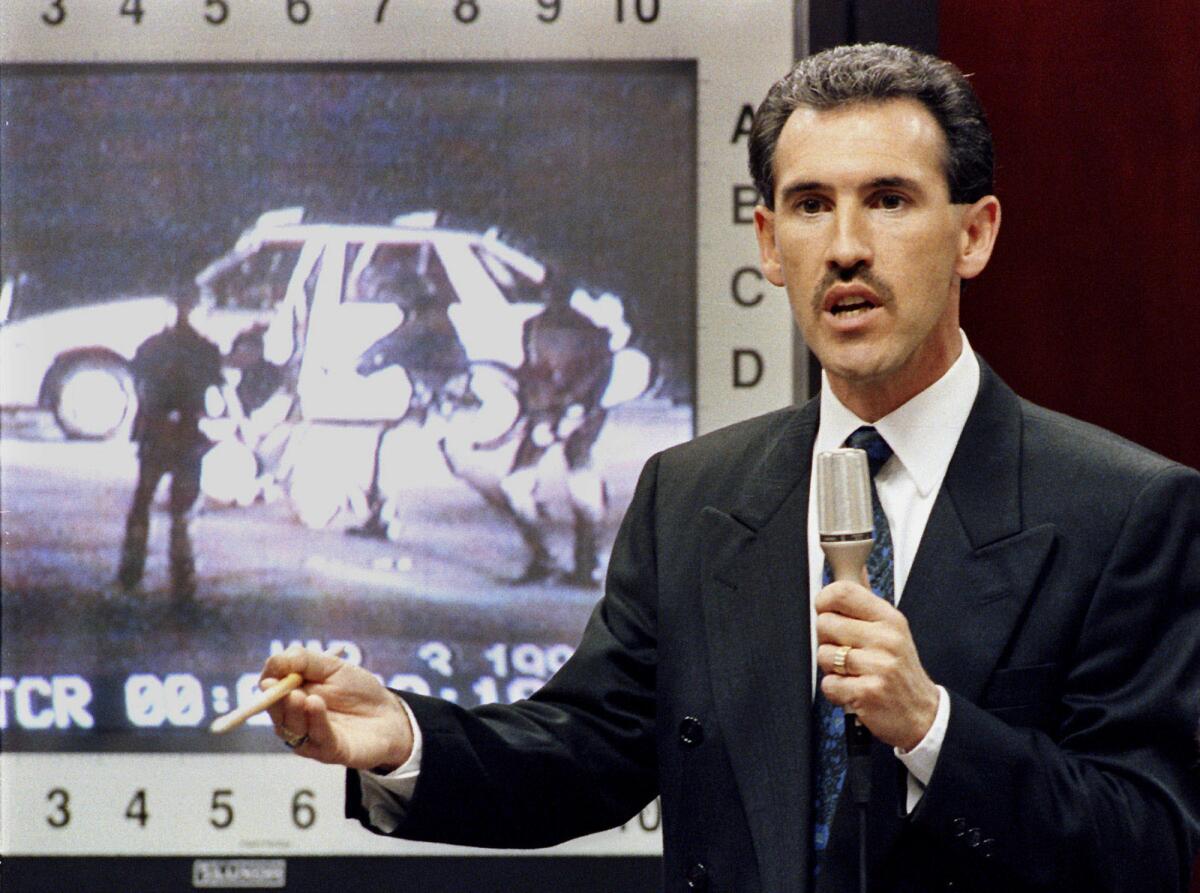

Theodore Briseno, one of the officers acquitted in the King beating, was half Mexican. More than half of the people arrested and about a third of the dead were Latino.

Three of the first four people killed, including Cañedo, were Latino. Guatemalan immigrant Fidel Lopez was pummeled, spray-painted black, doused with gasoline and left for dead at the intersection of Florence and Normandie just an hour after the far better known assault of Reginald Denny.

The reaction among Latinos at the time was shock and shame, with a community-wide question that doubled as an interrogation: Us?

Politicians and pundits stumbled for answers. Latinos in more established communities like East Los Angeles looked down on the affected as chusma — lowlifes.

When my eighth-grade social science teacher at Sycamore Junior High in Anaheim stapled riot coverage from national magazines to the classroom wall, we Latino boys were laughing so hard at the poor Latinos we saw that we tore the pages down.

Yet history has reduced Latino involvement to an afterthought in a master narrative of Black rage against a racist white system, with Koreans in the middle.

Those who lived through those times say such an oversight comes at our own peril.

Rubén Martinez covered the riots for L.A. Weekly from Pico-Union, the longtime gateway for Central American migration.

His vivid dispatches of what he described as gente afligida — oppressed people — breaking into stores for daily essentials put him in demand locally and nationally to explain why Latinos were rioting.

He quickly tired of the role. “Anyone who actually paid attention before could’ve told you exactly what was going to happen,” he said recently.

Martinez, now an English professor at Loyola Marymount University and author of several books, said that attention disappeared as quickly as it came. A “reerasure” of Latinos and the riots took over.

“When we reduce it to simplistic narratives — that this is a Black thing, this is a white thing — and we can’t take the extra step in telling it in its complexity, we’ll keep getting blindsided by events like 1992,” he said.

Manuel Pastor, director of USC’s Equity Research Institute, wrote a paper in 1993 that mapped out Latino involvement in the events of the previous year and detailed the failures of the L.A. establishment to anticipate what happened.

He warned in the conclusion of the paper, written for the Tomás Rivera Institute: “If we are to prevent another outburst, we must focus on the underlying economic and social problems which confront us.”

Thirty years later, Pastor says his summation remains as relevant as ever.

“So much of the Latino unrest was about the situation of working poverty,” he said. “But everyone pays a lot more attention to the spark rather than the tinder.”

::

Eduardo Cañedo, Jr.. was born five months after his father’s murder.

Growing up, he wondered how and why a Mexican would be targeted in an event that his teachers in Arvin described as a “Black-white thing.”

Cañedo Jr. eventually began to watch riot footage on YouTube, hoping he might become a detective one day and track down his father’s killer.

That’s when he realized that Latinos played such a prominent role in the riots, which upset him.

“I thought, ‘Why are they doing that?’” said Cañedo Jr., 29, a foreman for an auto parts company in Salome, Ariz. “They shouldn’t be doing that. It has nothing to do with what happened with Rodney King.”

Aurea Montes-Rodriguez, who had just moved to Compton from South L.A. as a 17-year-old with her Mexican immigrant family, said her Black neighbors felt the same way.

On the second day of the riots, she and her brother drove around in his pickup truck and saw “a lot of Latino immigrants” ransack a Top Valu Market near their home.

“When we got back to our house, one of our neighbors [said] ‘We are not going to allow for looting to come onto the street,’ and I felt like he was specifically speaking to us, as Latino immigrants,” she recalled.

Some longtime Black residents in South L.A. and its surrounding majority-Black cities resented the influx of Latinos that would radically transform the region in the coming decades. But Montes-Rodriguez didn’t think much of her neighbor’s comment until five days later, when she was in Washington D.C. at a youth leadership conference.

“When people found out that I was from South L.A., most of the questions were, ‘How could your people burn down their community?’” she said.

This time, they were referring to Black residents.

“It was the first time that I heard anti-Blackness in such an explicit way,” she said. “And I think that people talked to me that way because I am Latina, because I am brown.”

Soon after, Montes-Rodriguez committed herself to South L.A. as a home and a cause, helping Latinos rebuild alongside their Black neighbors — a founding plank of Community Coalition, where she is the executive vice president.

The nonprofit’s president, Alberto Retana, was a teenager in La Habra during the riots. He remembers seeing television coverage of Latinos breaking into stores and feeling “disturbed to see all the brown faces in such poverty. I didn’t know that world.”

Forgetting that history, he said, lulls people into thinking that Latinos are above civil unrest, when the present moment is a “powder keg” similar to the years leading up to the riots.

“We shouldn’t be so naïve,” Retana said, “to see that inequality is far worse now than then.”

In his office is a painting replicating a 2016 photo of a young Black woman in a flowing dress standing off against Baton Rouge police during anti-police brutality protests. Behind it are images of Black and brown activists after the L.A. riots, united.

While some younger people are learning about Latinos’ role in the “rainbow rebellion” of 1992 via social media and organizations like Community Coalition, he said, much of the history has been lost to everyone else, especially newcomers who weren’t around back then or were too small to remember.

“Latinos were seen as a non-permanent part” of the unrest, Retana said. “It’s baked in this idea that they were Black and Korean. What is it about our city’s shame about the riots that even though [it involved] brown folks, that we can’t re-center that experience?”

If there are citywide disturbances again, Latinos will likely be at the center of them, by default. We’re a plurality across Southern California, a majority in Los Angeles. We won’t be ignored again — or else.

::

For years after her husband’s death, Rosa Bañuelos Ortiz lit a votive candle, putting flowers and a photo of him beside it every April 29.

“He would always say, ‘Honey, when I’m working, you’ll never lack for anything,’” she said. “Since his death, it’s been nothing but work.”

The 56-year-old Bañuelos, who lives in Bakersfield, still works in the fields. In a couple of weeks, she’ll join the grape harvest.

Neither she nor her children have ever visited Cañedo’s tomb in Mexico. His family there has never shared its exact location.

His survivors were thankful and amazed that I tracked them to hear the story of their patriarch. They agreed that his murder should symbolize something more than just an unlucky death.

“Rioters killed my dad,” said Eduardo Jr., who keeps a painting of his father commissioned by his mother shortly after his death. “He was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I can’t be angry against them as I get older. But he at least deserved to be remembered more.”

“People like my dad had to suffer the consequences of actions over things that they had nothing to do with,” said his other sister, Carolina Sarmiento, as she held her bawling two-year-old daughter.

Mayra said that when protests hit Bakersfield in 2020 in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, she stayed home.

“Who knows what could’ve happened if I was there?” she said.

Everything they know about the night Cañedo died was pieced together from his friends and the Arvin police officers who knocked on the family’s door at 4 a.m.

After Cañedo picked up a second friend for an early dinner, his Taurus developed engine problems.

At around 6 p.m., he pulled off the freeway, stopping on Slauson east of La Cienega in Ladera Heights.

His two friends went to a pay phone to call a tow truck, while he stayed behind with the car. When the truck didn’t show, they went off again around 9 p.m. to try and find a mechanic somewhere, anywhere.

They returned to yellow caution tape around the Taurus. Inside, Cañedo was dead from a bullet to the pancreas.

His murder remains unsolved. No one from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department has ever contacted the family with an update.

“Se quedó en el olvido,” Bañuelos said, with a sadness to her voice.

He was forgotten forever.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.