L.A. has no seasons, you say? Wrong. Here’s how to mark them

- Share via

People who say L.A. has no seasons are unobservant dunces.

Of course we have seasons, and we have a lot more than four seasons. We have, for instance, the long “When the hell is it going to rain?” season. We have the brief “When is it going to stop raining?” season, the “Do I smell smoke?” season, and the “Sweater or sweatshirt?” season.

For the record:

2:54 p.m. July 4, 2021An earlier version of this column incorrectly said that bougainvillea is native to South Africa. It is native to South America.

Right now, we are in the “Oh great — now I have to clean those damn jacaranda blossoms off my car” season.

In other places, bare branches and dead flora are an easy seasonal tell. Here, you have to look closer at what’s flourishing when. Right now we are at the tail end of a rather long jacaranda bloom that turned trees into ultraviolet canopies.

To understand the landscape you see, you have to realize that— like you — it is probably not from around here.

Jacaranda, which hails from Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay, went viral thanks to the influential botanist and ornamental horticulturalist Kate Sessions, a California native who painted the early 20th century landscape with plants (imported and native) the way Monet painted canvases with water lilies. The earliest jacarandas might have been brought here a few decades earlier, when Gold Rush-bound ships stopped in South American ports, and the passengers may have decided to take some of that shimmering, lilac-blue beauty with them.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

I know about this because Frank McDonough told me. He is an ace botanist and, for almost 25 years, the botanical information consultant at the Los Angeles County Arboretum, which any resident who claims to be a real Angeleno must visit. It posts an annual bloom calendar, as does the Huntington Library, Art Gallery and Botanical Gardens, so you can find out in these brilliantly maintained gardens what is coming and going, month by month, in the larger Southern California landscape.

From him, I learned that what green L.A. looks like now bears almost no resemblance to its pre-human self. L.A. was once wetlands fed by the cobweb streams and marshes of the L.A. River. It had oak woodlands and grassland valleys.

Then, at least a thousand years ago, Native Americans were burning land to flush game and to make more oak trees grow to make more acorns to eat.

It’s the last hundred-plus years that made the native landscape unrecognizable. Before Los Angeles Aqueduct water drenched the San Fernando Valley, in 1913, dry wheat farming was so bountiful that L.A. wheat was sold as far away as China. But sexy, succulent citrus tipped the balance — the orange icon that tourists were told you could pick out of the window of your train, and out the window of your kitchen in your new L.A. house.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

“It was lucrative, to say the least,” McDonough said. Orange growers brought in veteran arborists, especially from Italy, who made a science of bigger and better citrus, he said. For many years after, before the gray tang of smog replaced it, orange blossom fragrance made the inland valleys from Pasadena to Riverside smell like a society wedding.

California has native roses and grapes, but too scrawny and scraggly for Europeans’ liking, so the Spanish fathers brought their own grapevines — and corralled Native Americans to cultivate them. (“Fresno” was a 1986 miniseries that mocked nighttime soaps like “Dynasty.” In its opening sequence, a conquistador eats a California native grape, makes a face, spits it out and says, “You call these grapes? They taste like … fresno.”)

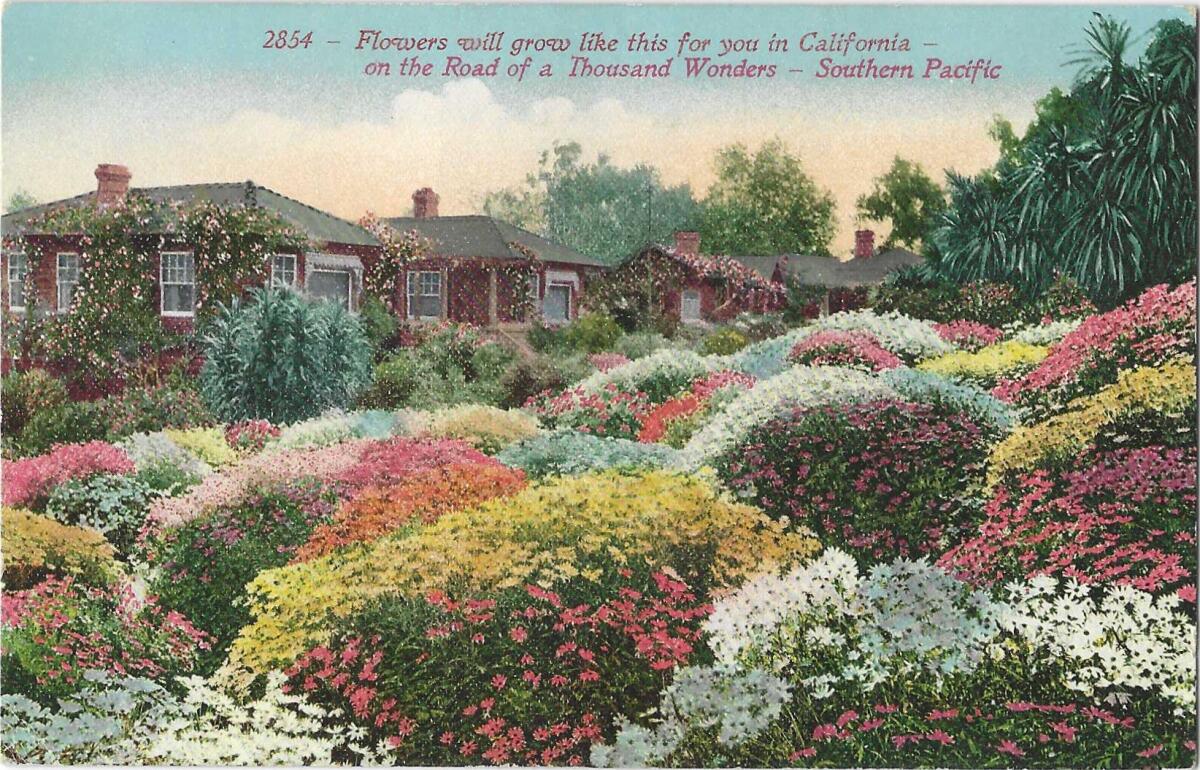

The Chamber of Commerce got lucky; at the turn of the century, when it was pitching L.A. as the garden of the world, millennia of alluvial water had made the soil so rich that you really could practically stick Jack’s magic beans into the ground and up would pop a giant beanstalk. The garden of even the humblest L.A. cottage could look as exotic and splashy as the window of a Fifth Avenue florist.

“Because of what I would call a propaganda campaign to help develop the land,” says McDonough, “because of that we are one of the most horticulturally sophisticated areas in the world. It doesn’t seem like it, does it? But we are.”

“Remember the number-one industry was selling land. They pushed the idea that you can grow anything you want in California: ‘We have plenty of water! Look, green lawns! Look, elm trees!’” — even if in the long run, there might be no long run.

And then, Southern California was terra incognita — a new, unsettling and unsettled place that made newcomers nervous. The research, says McDonough, has found again and again that “highly maintained landscapes make us feel safe because we know there’s somebody close by, working on them. Untamed, wild-looking areas don’t make us feel safe.”

The transplant plants that newcomers brought from their old homesteads flourished like mad, in part because their usual enemies — insects and diseases — were left behind. In time, insects finally did find the L.A. buffet and began to feast on these plants, and with no natural parasites here to stop the bugs, ag business then had to import parasites to go after the insects. As McDonough says, “That is a legacy of the citrus industry — introducing parasites.”

Most of what we could call our charismatic megaflora was hauled in here from elsewhere, and it throve. It’s a delish paradox that the palm tree, second only to the orange in iconography, has no native version in the L.A. basin. The closest grows in the desert canyons around Palm Springs.

If L.A. has a single mascot palm, it may be the shaggy-skirted one that was moved to Exposition Park in 1914. Before that, it spent a quarter-century greeting new arrivals at a train station, and even before that, around 1850, the year of California statehood, it had been dug up out of the desert and carted into town for its good looks. Prepping for the 1932 Olympics, workers planted 40,000 Mexican fan palms around town as set dressing for the summer games.

The flamboyant bird of paradise — the official city flower of L.A. — is an import from South Africa. Years ago, F. W. De Klerk, the South African president who controversially shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Nelson Mandela for ending apartheid, came to Los Angeles. I rode around with him for an hour or so for an interview, and several times, he interrupted to stick his arm out of the car window and point out South African plants and flowers that were now embedded in the L.A. landscape. In the 1960s, the city snubbed its own native trees to name another South African beauty, the coral tree, as our official arboreal symbol.

The elegant eucalyptus, the gray-green ghosts beloved of plein air painters and of citrus growers who planted it as a windbreak for their groves — they were Ellwood Cooper’s pipe dream. The PA-to-CA horticulturist thought that here, in what he thrilled over as the “paradise of the western world,” this Australian tree would be ideal for fuel (it wasn’t). And eucalyptus’ vaunted drought resistance, McDonough says, in fact depended on growing up in years of lavish rainfall alternating with occasional drought. Also, they light up like tiki torches in a fire. But now it’s hard to think of a Southern California landscape without them.

The prickly pear is as free-associated with the desert as a saguaro — there is one that’s native to Kern County — but here it’s tamed into backyard gardens and its fruit whirred into smoothies. My green-thumbed editor tells me that in the fall, guava trees make whole neighborhoods smell like the filling of a pan dulce.

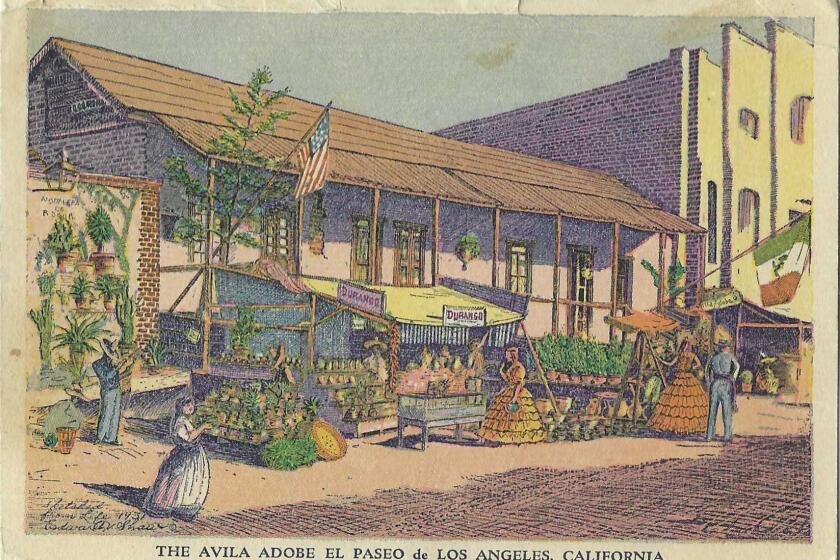

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

If you’ve come here from elsewhere you may have encountered the surprise and disappointment of Hollywood-movie-set blooms. They’re gorgeous, but sometimes as scentless as a picture of a flower.

Now, any number of plants here smell great. The wild vines of pink-budded jasmine in the spring must be what eternal paradise smells like. But flowers that elsewhere have a scent as potent as a certain local 1980s swanky perfume so strong it was ranked as an “elevator-gagger” and banned by some restaurants — their California version may let you down.

Why, in such magical soil, would that be? McDonough explains that smell is generally for pollinators, not for us, and in dry areas, pollinators like bats and moths emerge at night, or aren’t there at all, so plants don’t bother to put out fragrance. “All plants have an energy budget, and if you have a plant that continuously blooms, making scent is a highenergy thing” and not making scent could save energy and water. So be content to look, not sniff.

But every February for many decades, evenings in Los Angeles have been scented with what your nose understandably misidentifies as orange blossoms. That’s the Victorian box tree, pittosporum, popularized a hundred years ago. But McDonough says they are dying off. Maybe, he speculates, it’s because they’re clones cut from the same original plants. And there’s also a tree-killing malady called canker fungus, which we make worse by using chainsaws, “which spread the fungus spores like crazy, and blowers, which spread the fungus like crazy.” Like a doctor washing hands between patients, McDonough advises, gardeners should clean their pruning tools between trees.

Watch your calendars, and your gardens, and the flora of our streets.

Jacarandas have closed up shop for the year, but in July and August, crape myrtle trees, with their pink-and-violet palette, natives of Taiwan, can be just as dramatic.

McDonough is partial to the floss silk tree, which will soon be showing off with blooms like tiny orchids above a spiky trunk that looks positively Jurassic. The biggest pink floss silk tree around — maybe 90 feet tall — is at the Bel-Air Hotel, planted there by Alphonzo Bell, the developer of Bel-Air, philanthropist, and one heck of a tennis player. The hotel stands on property that was once his home.

Every page of the L.A. calendar delivers some delight in leaf or petal — even the autumn, when McDonough says the gathering of the world’s trees at the Arboretum can make it as vivid as a little Vermont, and far more exotic. The motto of the website California Fall Color is, “Dude, autumn happens here too.”

Add botanical gardens and vineyards to your list of places to see changing leaves.

After reading this, if you’re inclined to choose sides, “native plants” versus “non-native plants” (surely there are T-shirts?) McDonough thinks that’s the wrong attitude. The real conflict is between water-thrifty plants and water-extravagant ones: Team Sippers versus Team Suckers.

McDonough used to get annoyed at the latter, at English-garden landscapes and year-round lawns thick as carpets and green as Masters Tournament jackets. But with water prices going nowhere but up, he is certain that “the market will take care of that.”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.