More than a big, flat suburb: Why the San Fernando Valley is so important to California history

- Share via

Death Valley, the Central Valley, Silicon Valley — meh.

Here, there’s only the Valley. The San Fernando Valley, for way too long the Rodney Dangerfield, the red-haired stepchild of Los Angeles.

Anywhere else, the Valley — with its million and a half people in its 250-ish square miles — would be the massive star at the center of its own civic solar system.

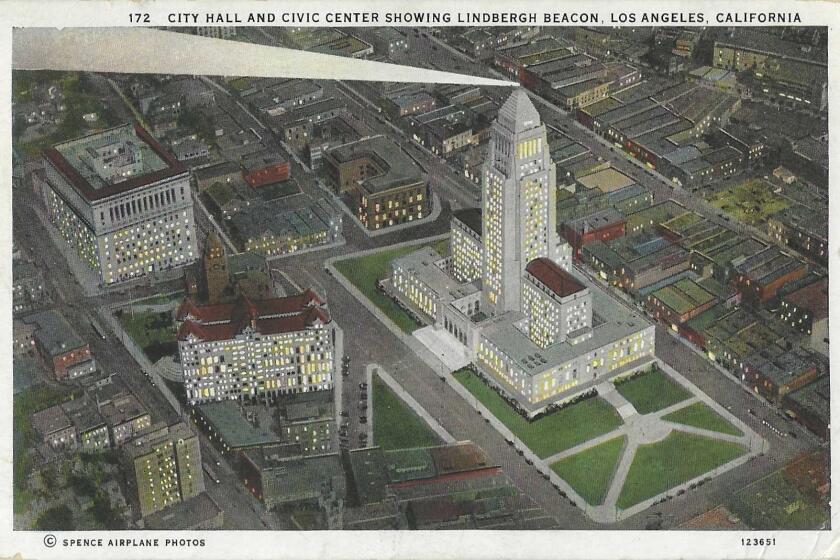

But most of it lies within the Los Angeles city limit signs — about half the acreage of L.A., when you add it up. And so the Valley sometimes finds itself playing dress extra to Hollywood, and chasing the tires of City Hall’s official vehicles.

The only modern mayor from the Valley was Sam Yorty, son of Encino, who served from 1961 to 1973 and whose bust stands in the Museum of the San Fernando Valley. The Valley’s self-regard also sustains the Valley Relics Museum, where the Valley of yore and lore, of carhop drive-ins and a celebrated honky-tonk called the Palomino, live on in their neon signs.

Two decades ago, when Kevin Roderick wrote his book “The San Fernando Valley: America’s Suburb,” the title “was a little dated even then,” he says today. “But it’s even more dated now, because now it has its own suburbs, and became an integral part of Los Angeles a long time ago in terms of culture and demographics and who lives there and what goes on there.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

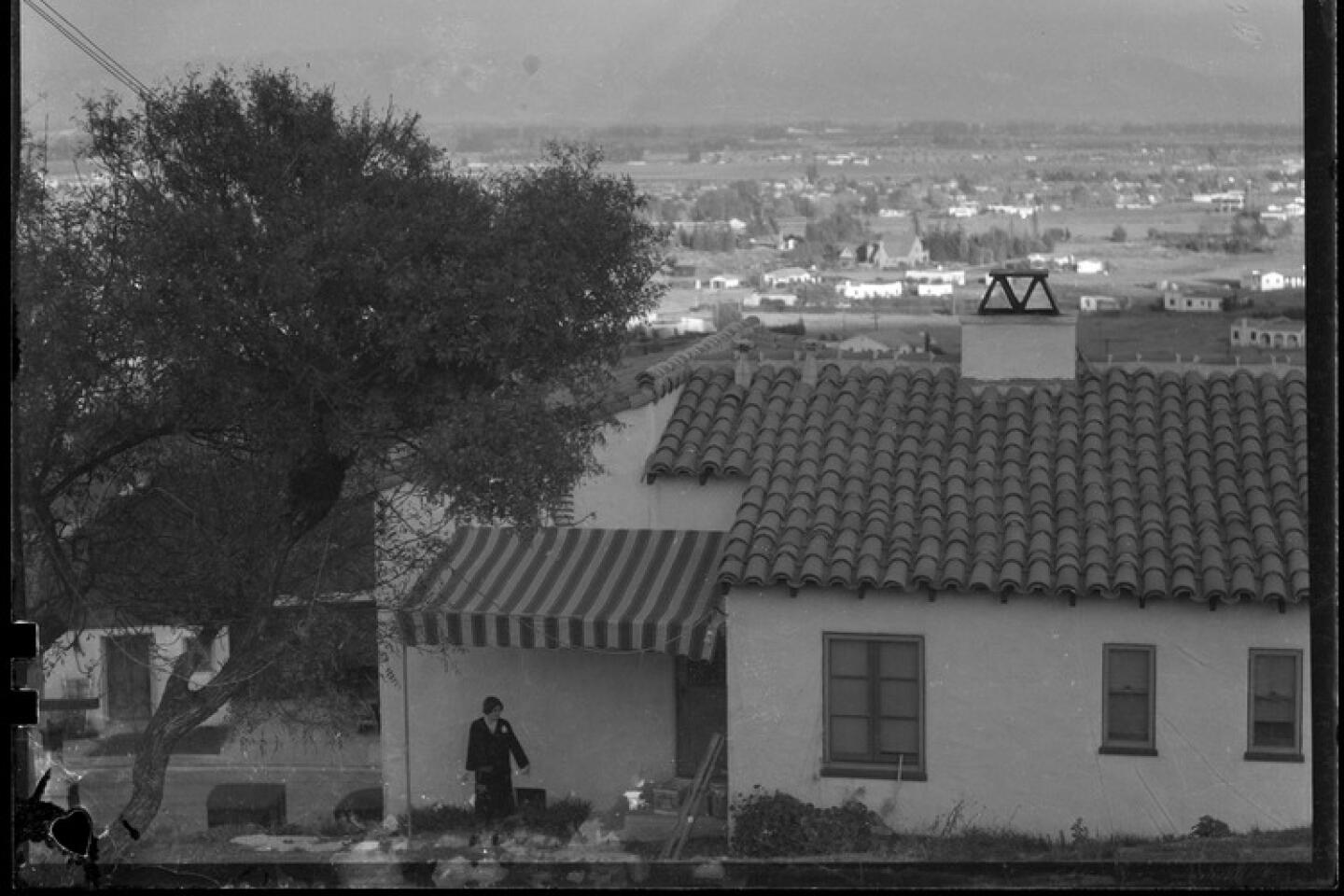

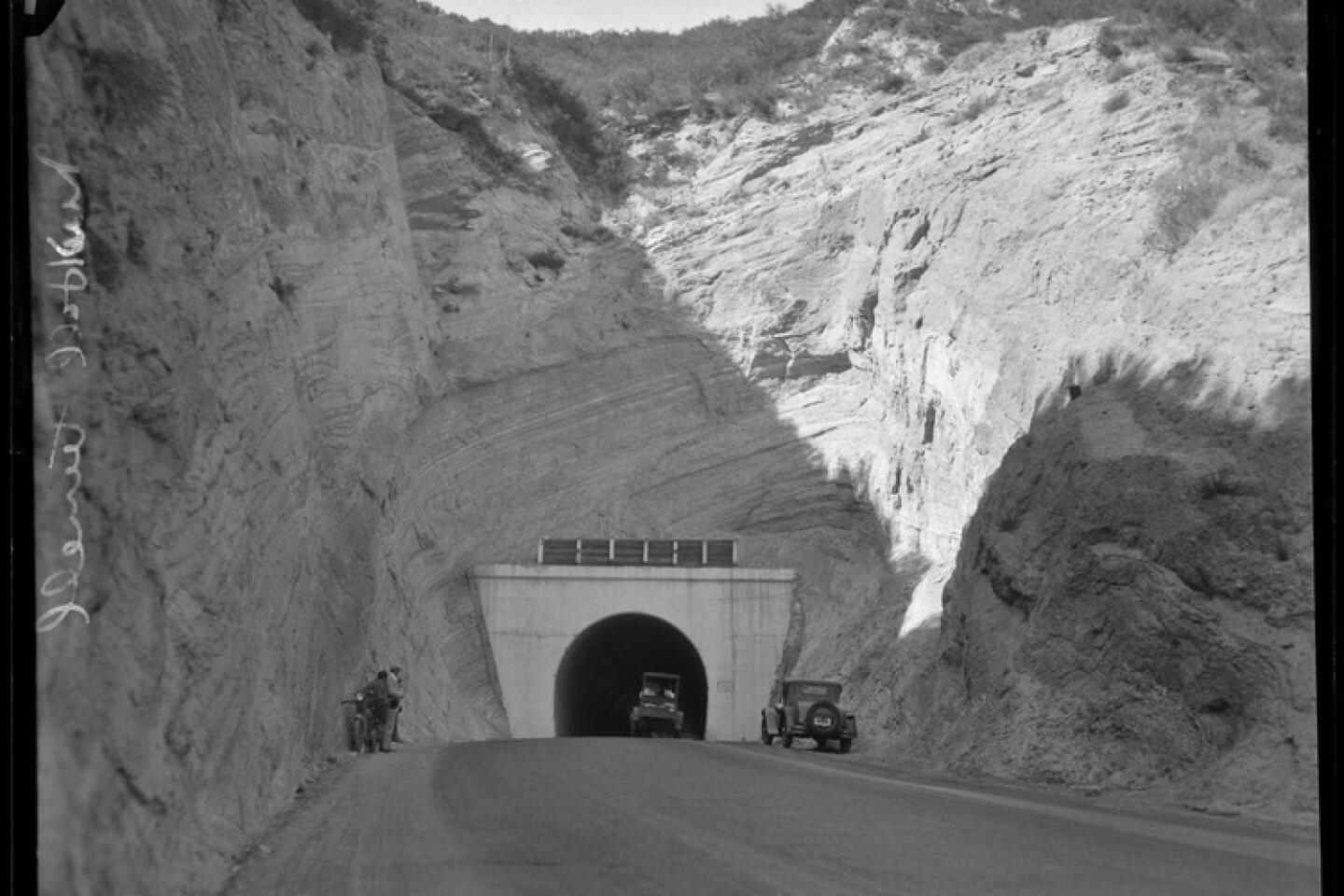

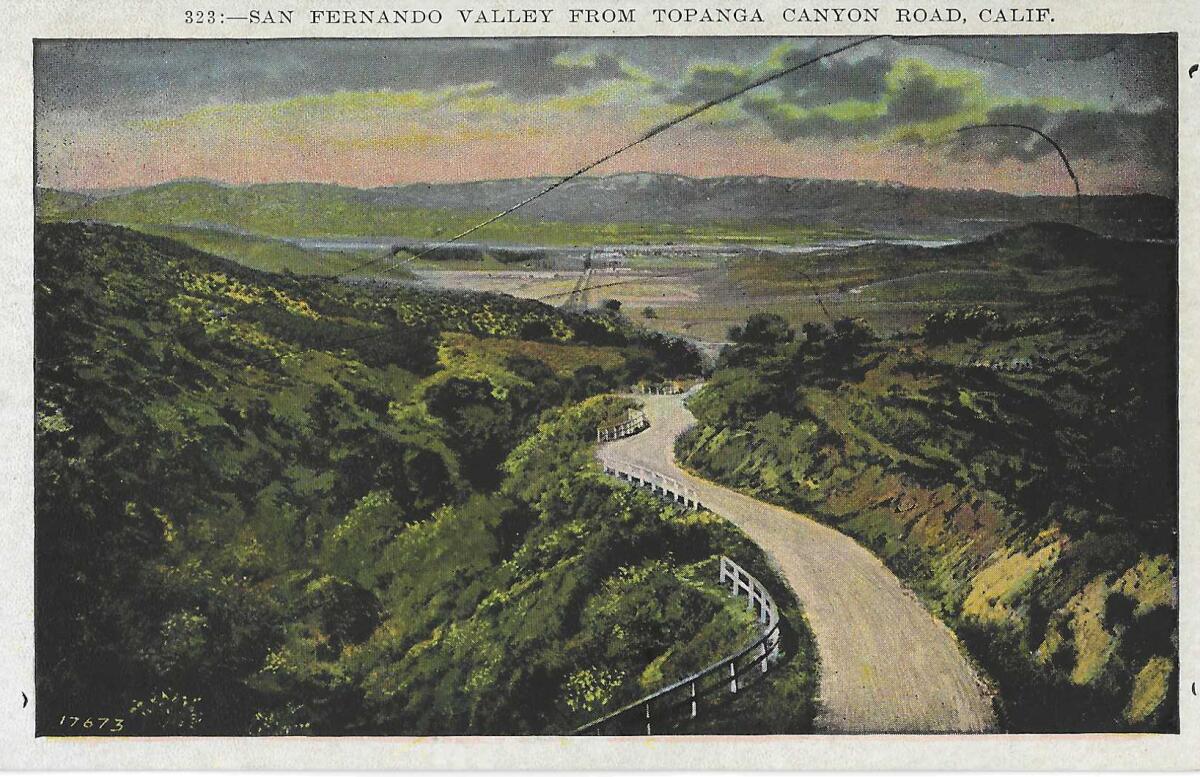

In 1797, the San Fernando Mission became the first intrusion into 70 centuries of Native American life in the Valley. About 10 years after the Civil War, men with the ring-a-bell names of Lankershim and Van Nuys commenced vast “dry farming” of wheat and barley.

The big citrus groves that once wafted the bridal scent of orange blossoms across the land lay farther to the east. But the Valley, chopped down and cut up from the Mexican land-grant kingdoms, had pleasant little farms with pleasant little groves of walnuts and peaches.

The Valley kept on subdividing itself into ranches and ranchettes, into the rustic paradise of the song that left GIs yearning: “I’m gonna settle down and never more roam, and make the San Fernando Valley my home.”

Ah, one man’s dream is another man’s punchline. In “Ghostbusters II” in 1989, Bill Murray’s character chastises the reincarnated Carpathian genocidal sorcerer: “If you had brain one in that huge melon on top of your neck, you would be living the sweet life out in Southern California’s beautiful San Fernando Valley!”

The Valley has outlasted many of its stereotypes. The white middle-class suburbia of restrictive covenants is now as diverse as the core of L.A. itself. The “Boogie Nights” Hollywood-adjacent factory for porn movies was run off by condom regs and online X-cess. The addled Valley girl of irritating vocals (“Fer SHUR, TO-tally) and her natural habitat, the Sherman Oaks Galleria, was a subculture more lasting in film than in fact.

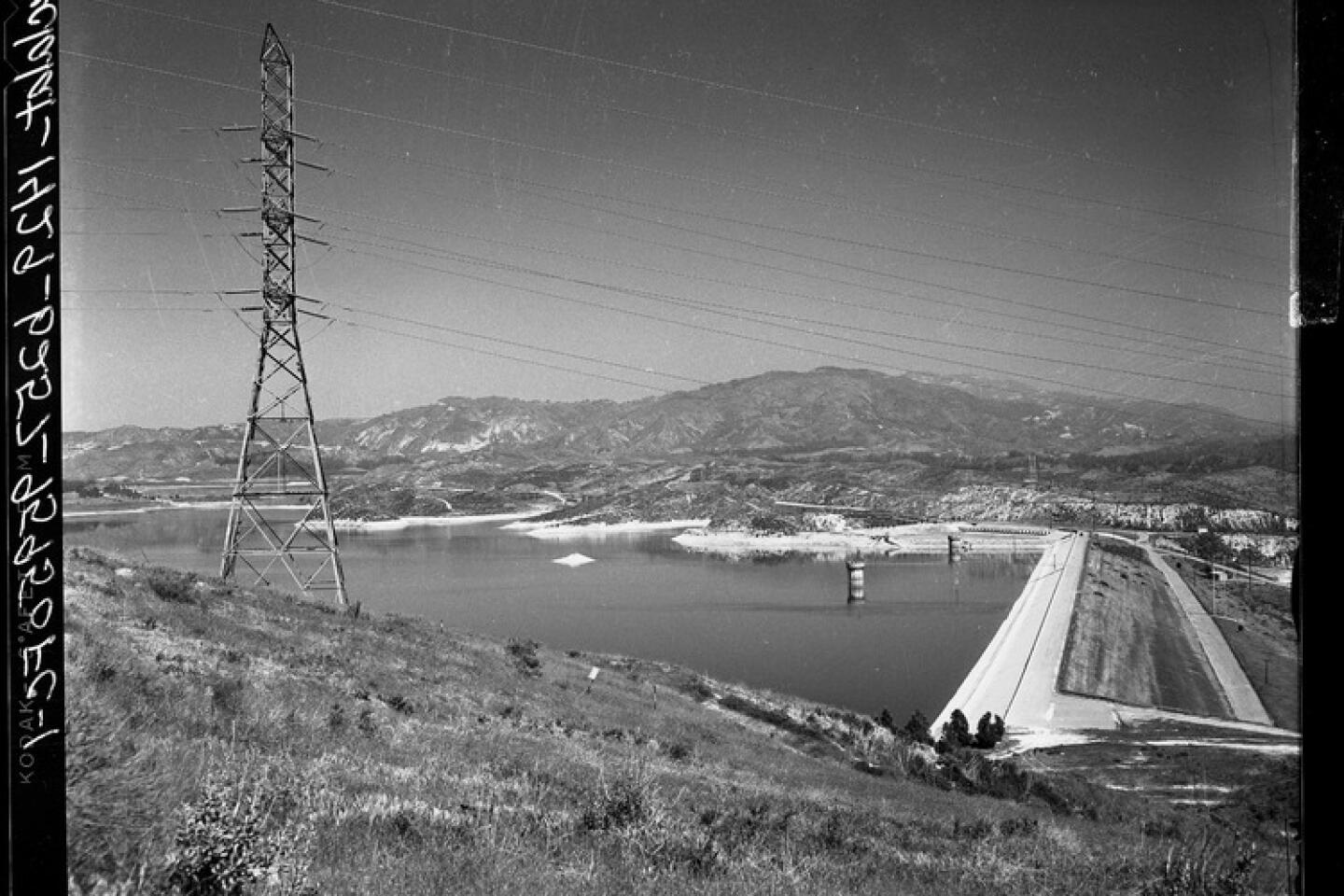

You could probably tell the Valley’s history in movies. “Chinatown,” for one. In 1905, the city of L.A. won a lawsuit forbidding Valley farmers and ranchers from tapping into the water under their own feet. L.A. stuck water meters in the ground just to ram the point home. The city would soon stick a 233-mile-long concrete straw into Owens Lake and suck up that water too. The farmers were being “droughted out,” and a downtown consortium was buying up Valley land on the cheap and sometimes on the sly.

When the vast Valley was annexed by L.A. in 1915, historian Kevin Starr called it the Louisiana Purchase of Los Angeles. Fourscore and seven years later, the Valley’s disaffection peaked: It tried by the ballot to secede from L.A., and damn near succeeded.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

Roderick says now it’s about “internal secession. Drive around the Valley today and you see a lot of blue ‘community’ signs’” designating mostly dreamed-up names for neighborhoods that want to break away from bigger neighborhoods. “I grew up in Northridge. My little corner is now called Sherwood Forest.” When it happened, a councilman from central L.A. remarked, “I’m going to change my name to Robin Hood.”

Don’t go hunting for Michelin stars, but actual stars may appear along Ventura Boulevard, the Valley’s Restaurant Row. There’s superb sushi. Casa Vega, opened in 1956 and was the setting for a cocktail scene in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” The vanished Rondelli’s, now a bar-and-seafood spot, but in 1959 the site of a mobster rub-out right in front of the notorious Mickey Cohen. (Who says the Valley has no nightlife?) And Sportsmen’s Lodge, a rustic hangout where Bogie and Bacall drank, and Clark Gable came over from his Encino ranch for dinner. Ron and Nancy Reagan drove here for their wedding reception after getting married at the Little Brown Church in the Valley.

Some Valley highlights to amaze your friends:

Marilyn Monroe was “discovered” working at a Van Nuys defense plant during the war.

Two months before Woodstock, about 200,000 people streamed through Devonshire Downs for “Newport ’69,” a chaotic open-air concert weekend with Creedence Clearwater Revival, Marvin Gaye, Jethro Tull, and a fierce Jimi Hendrix.

A dozen years earlier, on the opposite side of the Valley in Pacoima, a high school kid named Richard Valenzuela (stage name Ritchie Valens) was making his mark on rock ‘n’ roll.

Robert Redford’s 1990 diss in the L.A. Times is a generation too old for present Valley-ites: “When we moved to the Valley, I felt like I was being tossed into quicksand. There was no culture.” There’s no MOCA North, but there are community theaters. The Valley’s had a chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution since the First World War.

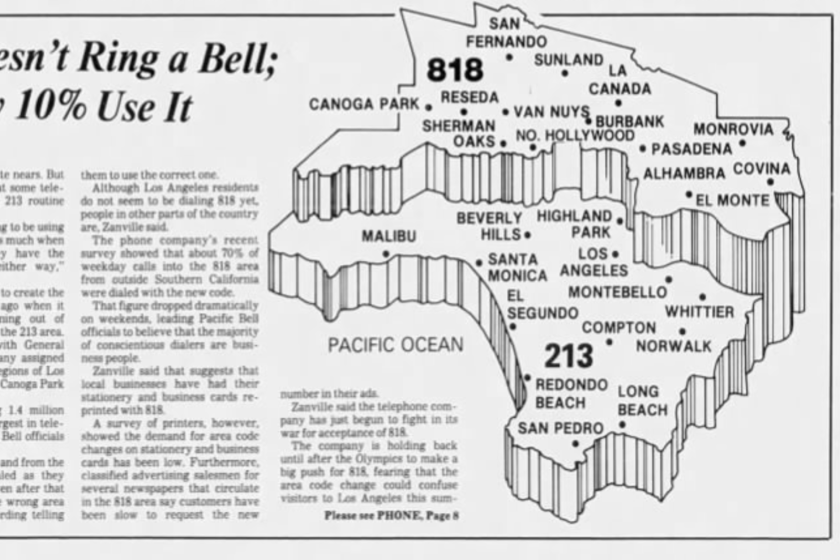

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

Beverly Hills claims the motion picture academy, but North Hollywood has the television academy, with the enormous golden Emmy statue out front.

The Valley did nothing for Susan Sontag, the future public intellectual transplanted from New York to North Hollywood High, where her precocious teenaged self edited the school newspaper, looked down at the entire English faculty, and, so said her unimpressed gym teacher, “spent most of her time avoiding physical exercise.”

In Calabasas, there’s a pet cemetery, founded in 1929, and L.A.’s cultural landmark No. 1, the Leonis Adobe, built in 1844 and barely rescued from getting wiped out to build a supermarket.

If you want the visible proof of the Valley’s agricultural past, there’s Pierce College, a community college in Woodland Hills, almost 75 years old and still teaching agriculture and farming. Old Valley hands remember going to Pierce to buy their milk and eggs courtesy of the cows and chickens in the ag program’s working farm. The farm’s still working, and so is the college’s weather station, one of the nation’s oldest.

Before it was bulldozed in 2006, a 22-foot-tall tower of hundreds of wooden beer pallets from the old Schlitz brewery in Van Nuys was a kind of down-market Watts Towers. L.A.’s Cultural Heritage Commission declared it to be a cultural monument in 1978. By way of explanation, Commissioner Robert Winter, an architectural historian of note, offered this: “Maybe we were drunk.”

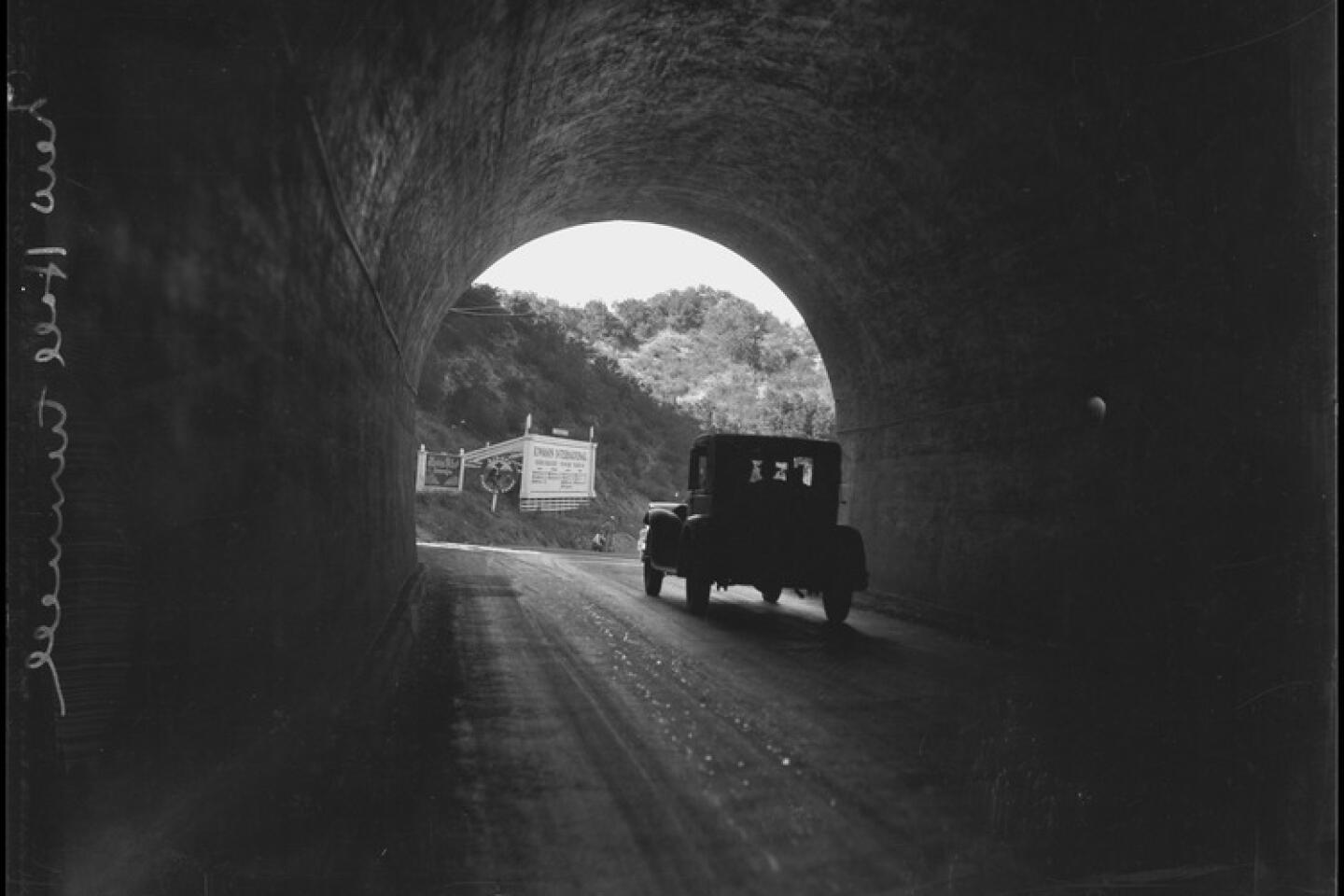

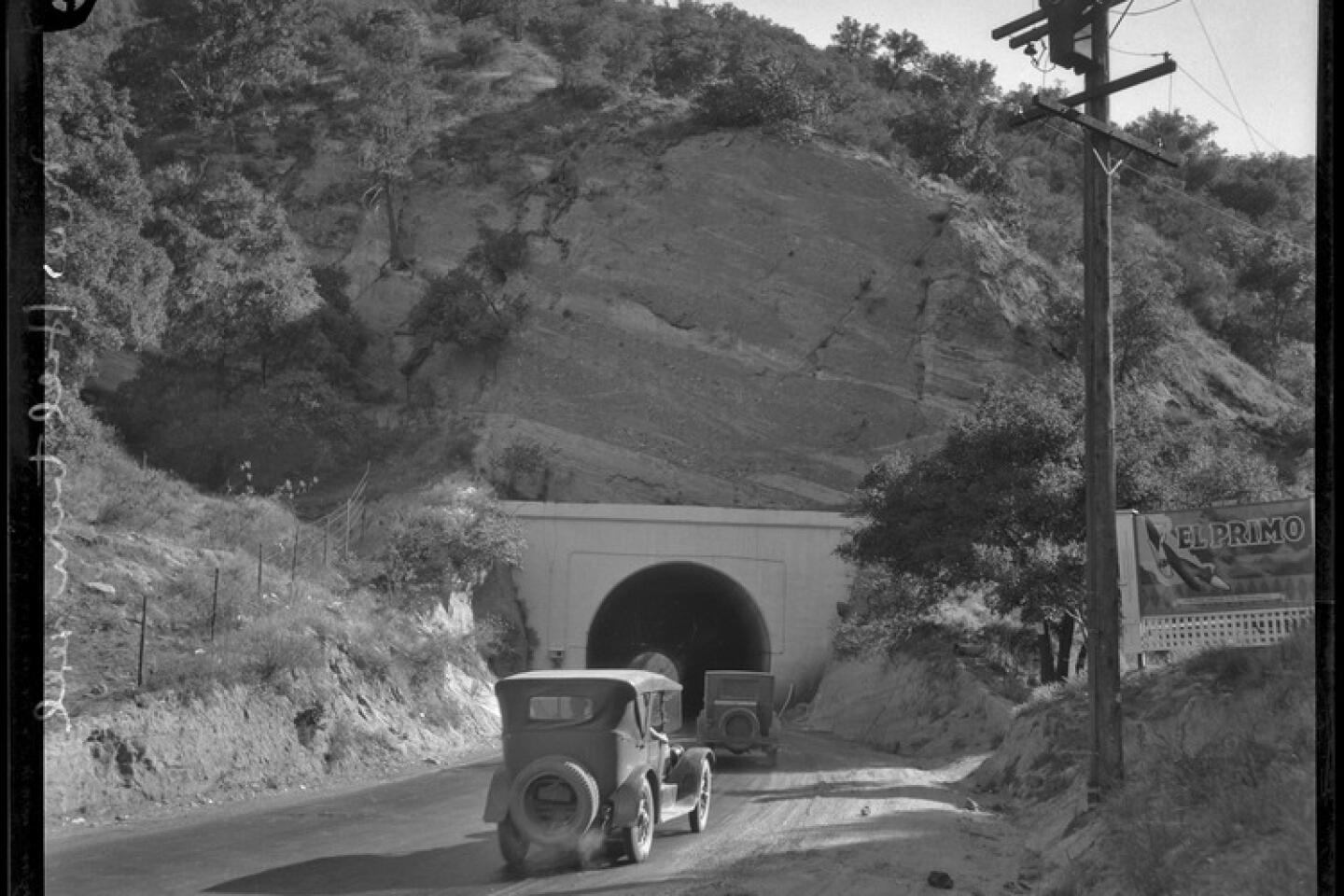

And best-ever Valley detail: When the Red Car rail lines arrived in 1912, the Valley still had no undertaker, so a designated “death car” carried the Valley’s defunct over the pass and into L.A. for undertaking.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.