Column: Citrus in December is a SoCal tradition. Enjoy your harvest while you can

- Share via

Every December in Southern California, the days get shorter yet brighter — and it’s not Christmas lights or the shifting sun that make the region shine.

I’m talking about citrus.

Trees heavy with fruits that ripen through the color spectrum as winter progresses are as much a Southern California holiday tradition as tamales and the Rose Parade. Santa might not get you the present you want, but he’ll bring you oranges and lemons, as co-workers come into the office with bags of them or neighbors leave a few at your door. They’re tossed into our lunches for a quick snack, cooked down into marmalade, sliced to make garnishes for platters or cocktails and thrown at people’s heads — OK, maybe just my cousins did that growing up.

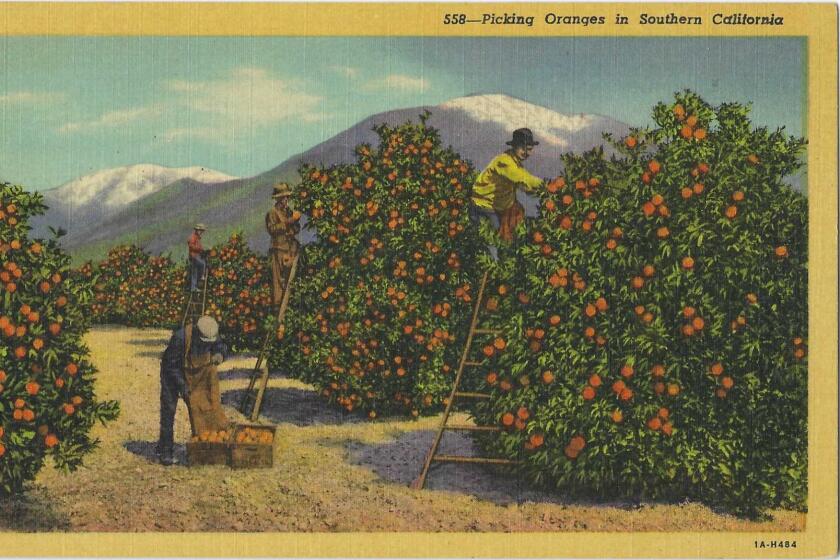

In Southern California, a long time has passed since our famed citrus crop dominated the landscape. The orange groves have instead gone to housing developments, nearly every one.

Seeing these bounties during the season of giving is especially poignant for me. My maternal grandfather was a teenage naranjero — an orange picker — during the 1920s in Anaheim, when custom and law required that Mexicans like him live on the poor side of town and attend segregated schools, even as the local economy depended on their labor. My paternal grandfather worked as a bracero during the 1950s in an orchard that was eventually cleared to become a factory where one set of cousins worked during the 1980s, then torn down for luxury condos where another set of cousins lived last decade.

That plot of land is within walking distance of the granny flat where I grew up. I have fond memories of walking with my dad on Saturday mornings to a nearby cannery, where we could buy big tin cans of freshly squeezed OJ still warm from being pasteurized. Today, in my small Santa Ana home, I tend to 11 citrus trees — some in the ground, some in pots. Citrus has turned from a symbol of exploitation for my grandfathers to a source of nutrition for my parents to a sign of the good life for me.

My wife and I grow the basics — massive Bearss lemons, Persian and Mexican limes, a kumquat bush that right now is so brimming with thumb-size orange jewels that it looks like a traffic cone. We also have rarities such as Australian finger lime, which gives a pinkie-size fruit that you cut in half, squeezing tart pearls into your mouth. I especially love our calamansi, a mainstay of Filipino cooking that you eat whole for a tart, peppery pick-me-up.

I just picked my blood orange tree clean, and I’m weeks away from a bunch of egg-size Indio mandarinquats. But this harvest will also bring death, because there are two trees that I need to kill.

One is a Pixie tangerine that just never took and that I’m going to put out of its proverbial misery — it happens. The condemned tree it really hurts to lose is a seedless kishu, among the sweetest of citrus fruits. It was among the first trees we planted when we moved in a decade ago, and it faithfully gave its delicious crop for years.

But a few Decembers ago, its branches turned into spindly things where spikes grew instead of leaves. The kishus became bitter. I hoped it was an anomaly, but the same happened this season.

It has been described as a Noah’s Ark for citrus: two of every kind.

When I get rid of these trees, that’s it. I can’t plant replacements. I live in a quarantine zone established last decade by the California Department of Food and Agriculture to check the spread of citrus greening, a disease that starves trees to death and that scientists have spent decades fruitlessly (pun intended) trying to cure.

The quarantine zone covers large swaths of Los Angeles, Orange, San Diego, Riverside and San Bernardino counties and keeps growing. Just a few weeks ago, agriculture authorities pushed it south in Orange County from Lake Forest to the San Juan Capistrano border. Nurseries within the zone can’t sell citrus trees to the public, and people can’t bring in trees from elsewhere. Technically, we’re not even supposed to share backyard fruit with one another.

Two-thirds of the 9,300-plus documented cases of citrus greening in Southern California were in O.C., according to state statistics. In 2018, I wrote about how I gladly let agricultural investigators onto my property to test for the disease. There were a couple of sickly looking specimens I figured had a date with an ax. Instead, the afflicted tree was the one I thought was my healthiest: a Thai lime that towered over my rose bushes and made the front of my house smell like a bowl of tom kha gai.

The gnarled fruit was nearly ready, and I futilely pleaded with state workers to give me just a few more weeks so I could pick it one final time. That wasn’t going to happen, and I didn’t fight their decision because I understood the severity of the disease. But my green thumb ached as workers sawed down the tree, took away everything — trunk, twigs, leaves, fruit, roots — in biohazard bags and tagged the remaining trees with a bill of clean health.

Citrus greening isn’t the first time Southern California citrus has faced an apocalypse. In the 1950s, another terminal disease called quick decline — also known as la tristeza, or “the sadness” — prompted farmers to bulldoze thousands of acres of orchards to make way for tract housing. Boosters nevertheless clung to citrus and its markers — the smell of orange blossoms, the crate labels with idyllic scenes of Old California — as proof of our subtropical paradise. Suburbanites joined the cult by planting citrus trees at their new homes. The Department of Food and Agriculture estimates more than half of California private residences have at least one.

The sight of my dying trees in the midst of flourishing ones is a reminder that we should treat citrus not as a metaphor for the California Dream but rather the fragility of it. Dangers loom all around us — climate change, the return of Donald Trump, precarious water sources. Even our backyard oranges aren’t safe.

Here for decades, gone in a season — and there’s little we can do except tend to what we have while we have it. Enjoy your harvest while you can.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.