South L.A. was promised a resurrection after 1992. The new boom could leave many behind

- Share via

The 1992 uprising that roiled Los Angeles put a spotlight on the socioeconomic injustice that bogs South L.A., bringing pledges of investment and community development.

Thirty years later, many families don’t have access to better jobs, grocery stores are still a rarity, and the investment that’s coming in is — primarily — making housing unaffordable.

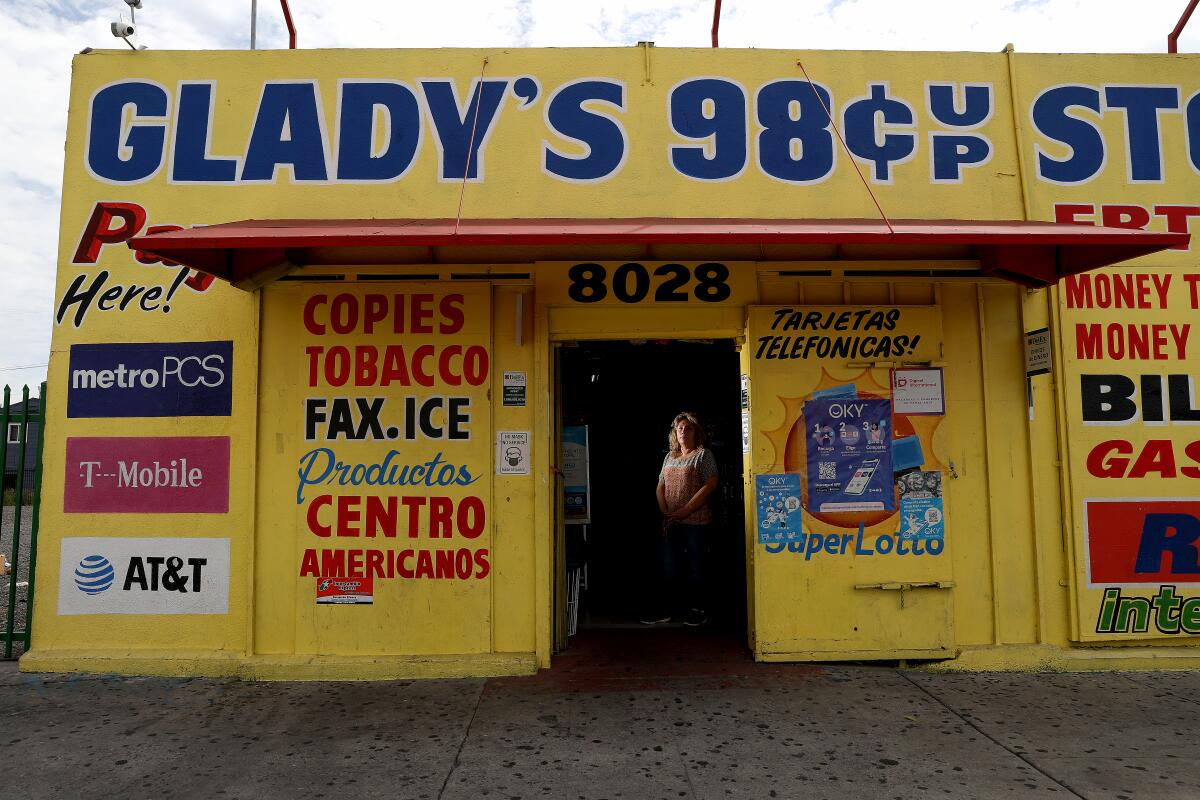

“People are still living on minimum wage,” said Gladys Colchado, a longtime business owner who runs a convenience store on Vermont Avenue in South L.A. “There’s just no way to succeed in this area.”

South L.A. — which encompasses more than 20 neighborhoods including Leimert Park, Baldwin Hills and Crenshaw — has had a complicated economic trajectory in recent decades.

There are still few large supermarkets in the region, meaning swaths of South L.A. have little easy access to fresh food, while in some neighborhoods the monthly rent on a luxury one-bedroom apartment approaches $3,700.

Home values in the area rose faster in the last 10 years than they did in the rest of L.A. County. Yet the median household income in South L.A. consistently lagged behind. In 2020, the median South L.A. household earned 60 cents for every dollar that the median household in the rest of L.A. County earned. (L.A. County data were calculated excluding South L.A.)

And things that are ubiquitous for many Angelenos are still hard to find in South L.A., making it feel disconnected from the riches of a state whose economy alone would rank fifth-largest in the world.

Gina Fields, a neighborhood council chair who grew up in South L.A., remembers going to a Macy’s at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw mall in 2015 to buy a swimsuit for an upcoming vacation. A store associate told her they didn’t carry any.

“I find it very hard to believe no one in the community except me wants a swimsuit,” Fields, who ended up buying one near her office in Century City, thought at the time.

While much of the rest of L.A. prospered, South L.A. was stuck in a cycle of inequity that left parts of the area seemingly frozen in time. That is because the underlying structural problems — a lack of good jobs, housing and labor discrimination, subpar schools — haven’t been meaningfully resolved over the decades, economists and other experts said.

“Ultimately, South L.A. has not benefited from a lot of the economic gains and increases that the city of L.A. has seen in income level rise since ’92,” said Deja Thomas, a researcher at the UCLA Labor Center focused on racial equity.

Fields, chair of the Empowerment Congress West Area Neighborhood Development Council, which represents 30,000 South L.A. residents, was a college student at UC Berkeley during the 1992 uprising.

She remembers coming home to see vacant lots that stayed empty for years. Burned-out buildings stood sentinel; when they were eventually torn down, there was no effort to rebuild.

Over the years, as Fields became more politically active, the difficulties of trying to lure grocery stores to the area began to frustrate her. The closest Trader Joe’s would get to the area was the USC campus, she said.

It’s a Catch-22, Fields said: If you can’t find the products you want, you don’t shop in the area — if you’re fortunate enough to have a car. If residents don’t spend money in the area, new stores don’t want to come to South L.A.

In 2020, South L.A.’s unemployment rate was 8.1%, compared with 6.2% in the rest of L.A. County, according to an analysis of the latest available American Community Survey data by Paul Ong, director of the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge. The median household income for the area was $44,000, compared with $73,000 for the rest of L.A. County.

“If you look overall and compare it over a half-century, it’s rather depressing that we have not made the progress that people have hoped for,” Ong said, noting a particular lack of significant improvements in public education.

The racial disparities in income among South L.A. households are even more stark.

White households in South L.A. had a median income of $84,000, compared with $48,000 for Latino households and $36,000 for Black households, according to Ong’s analysis.

In the rest of L.A. County, the median household income for white families was $91,000, compared with $61,000 for Latino households and $57,000 for Black households.

Opportunity and threat

South L.A.’s jobs deficit predates the 1992 uprising.

L.A. County’s sprawling aerospace industry was pummeled by the end of the Cold War and subsequent cutbacks in defense spending that led to mass job losses across the region.

Manufacturing plants for cars, steel and tires also shut down, which had an outsize effect on Black workers in L.A. “who tended to be last hired and thus the first fired,” said Manuel Pastor, director of the USC Equity Research Institute.

On top of that, jobs increasingly moved out of city centers — requiring workers to commute — while low-wage employment was on the rise, making good jobs less accessible and creating the conditions for those with the lowest skills and education to get stuck in hardship.

“We look at the riots, and we look at Latasha Harlins, we look at Rodney King, but we don’t look at the fact that people didn’t have jobs,” said James Fugate, co-owner of Eso Won Books, a Leimert Park institution.

At the time, the community was deprived of services and basic amenities, and businesses weren’t willing to invest in opening in South L.A., he said.

Many Black families were also leaving South L.A., and the area became majority Latino over time. Fields, the neighborhood council chair, remembers the “crunch on the Black community” then, as Korean and Latino communities started to move into South L.A.

“It felt like we were shrinking,” she said.

Recently, commercial and residential developers have started building in some vacant areas of South L.A., leading to interest in the area he hasn’t seen in the last 30 years, said Joe Rouzan, executive director of Vermont Slauson Economic Development Corp., a community development financial institution based in South L.A.

“Crenshaw’s hot right now. And Leimert Park has held on for all these 30-plus years,” he said. “Are they going to be moved out?” Rouzan said of residents and longtime business owners. “Are they going to be able to participate in this economic activity that will be long lasting? And will the community be the same?”

The change that is coming to the area is bringing fresh problems.

Baldwin Hills Crenshaw mall, where Fields struggled to find a bathing suit a few years ago, was recently sold to a developer with plans to remake it into a mix of housing, offices and retail stores. Community activists who were trying to keep it locally owned had mounted an unsuccessful bid to buy the property.

A new development in South L.A.’s West Adams neighborhood will include a Whole Foods supermarket, as well as a luxury high-rise apartment complex, where a one-bedroom unit could rent for as much as $4,800 a month.

And the Crenshaw Line, 8.5 miles of long-awaited light-rail line, is scheduled to open later this year, potentially bringing more visitors and revenue to businesses along its South L.A. path.

“With the Crenshaw Line coming from LAX through Westchester, straight down Crenshaw Boulevard ... suddenly the Crenshaw district becomes part of an overall opportunity,” said Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who represents parts of South L.A. in the 8th District. “That can be an opportunity, but it can also be a threat.”

Rents for businesses in Leimert Park began to substantially increase after plans for the Crenshaw Line were announced, said Adé Neff, founder and director of Ride On! Bike Shop Co-op on Degnan Boulevard, steps away from the planned Metro stop.

Business at the bike shop was already reeling from rail-related construction over the last few years, which prevented customers from reaching the store. Then, the pandemic hit. Recovery has been slow. He hopes for a turnaround when the line starts running.

“If it turns into a more walkable and bikable area, I think it’ll be beneficial for the businesses.” He is cautious. “The key is for the folks that have been here not to be displaced with all these developments,” he said.

Last month, the nonprofit organization Community Health Councils moved out of the red brick building on Stocker Street that served as its home for the last 30 years. It relocated to West Adams.

“We couldn’t buy in our area to stay in Crenshaw,” said Veronica Flores, the nonprofit group’s chief executive. “We couldn’t afford it.”

From March 2012 to March 2022, home values in South L.A. nearly tripled, just outpacing growth in the rest of L.A. County, according to data from Zillow.

South L.A. values as a whole still lag behind values in the rest of the county, posing an opportunity for home buyers priced out of other parts of L.A. As interest from outside the community supercharges the market, homes are increasingly unaffordable for longtime residents and locals.

“With prices like this, it’s so difficult for young people or anybody … to find a decent place to live, and I think overall, that’s very harmful to the community,” said Brenda E. Stevenson, a University of Oxford history professor who wrote “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender and the Origins of the L.A. Riots.”

“We’re going to continue to see what we’ve seen for the last 30 years, which is a forced migration of Black Angelenos into other parts of Southern California, and sometimes even out of the state, in search of more affordable housing and more affordable living costs,” said Thomas, the UCLA researcher, who runs a program at the university’s Center for the Advancement of Racial Equity at Work.

Building up the community

The Crenshaw Line is a case in point.

It could be an economic breakthrough for South L.A. It has also already pushed rents up for both businesses and residents in its path.

“It’s a mixed blessing,” Fields said. “We fought so hard to build up our community, and now there’s a real, justified fear that that community could be taken away from us once the improvements are made.”

Low-income communities of color, and especially Black communities, are typically cut off from other parts of the urban metropolis of which they’re part, Harris-Dawson said. That’s often cited as a reason private investment doesn’t want to be there, he said.

Government officials proposed the development of a light-rail or trolley system along Crenshaw Boulevard after the 1992 civil unrest to help rebuild South L.A.

County transportation officials at the time said such a project could create jobs, attract private investment in the area and bring new customers to local businesses, according to a 1992 article in The Times.

The line was finally approved in 2009 after years of sometimes contentious discussions and is scheduled to start running later this year.

Community members had pushed for more of the rail to be underground rather than at street level to minimize disruption to local businesses and to protect children who went to nearby schools. In the end, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority decided to run the train underground for the first three stops before it rises to street level on Crenshaw Boulevard near Vernon Avenue.

Community members and local officials also successfully lobbied for a station in Leimert Park, arguing that the stop would encourage commuters to come into the neighborhood and spend money and more businesses to open there.

Without that stop, “we wouldn’t be able to bring any jobs to the community,” said Jathan Melendez, a youth organizer with longtime South L.A. nonprofit advocacy group Community Coalition.

The Crenshaw Line will also open up jobs linked to the railway itself. And to get them, people in the community need training, advocates say.

“Our Black and brown young people need to understand what transportation jobs look like,” said Marsha Mitchell, director of communications at Community Coalition, which helped push for development of a vacant lot at Vermont and Manchester avenues, with community input.

That lot will become the home of the SEED School of L.A. County, a boarding school that will train students for jobs in the transportation industry. It’s being built through a public-private partnership on the 4.2-acre lot, which had stood vacant for 30 years.

A faded Payless Shoe Source sign on a pole still stands at the corner. Deeper in the lot are the foundations of the SEED School, set to open in August.

Half a mile away sits Glady’s 98 Cents and Up, Colchado’s convenience store, hard to miss with its bright yellow storefront.

Products jam every aisle from floor to ceiling. Clothes on hangers are scattered throughout, and toilet paper is stacked up.

Colchado remembers hiding at the back of the store with her family on April 29, 1992, as other businesses in the neighborhood went up in flames. Her shop wasn’t targeted and the family was unharmed.

Her business is a local success story, having weathered the uprising, recession and now a pandemic.

In the early 2000s, business blossomed. She leased the storefront next door, expanded her shop and hired a full-time employee to help out. She bought a home in Orange for her family, so her children could get a better education. She purchased investment properties in South L.A.

Then the recession hit Colchado hard. She lost all her properties, she said, except for her convenience store. She’s no longer the one-stop shop for the neighborhood, and she faces competition from other mom-and-pops, but is holding on hard.

“It’s my legacy, Colchado said. “When I retire, I want to be able to pass the store on to my children.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.