WATCHING THE California Elections : ...

It has been the off-camera campaign.

A race for the U.S. Senate in the nation’s most populous state has been hidden away in half-empty halls and in the living rooms of party faithful, while television news busied itself with the Olympics, the World Series and with presidential politics.

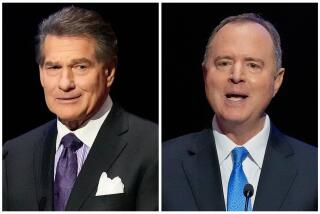

Nevertheless, the race between Republican Sen. Pete Wilson and Democratic challenger Leo T. McCarthy has not gone unnoticed. These two workaday politicians may represent the “bland leading the bland,” as one commentator dubbed them. But the candidates stand for very different philosophies of government, and they have their partisans.

Together, Wilson and McCarthy expect to receive nearly $25 million from a host of interested parties, including agribusiness, the movie industry and the pro-Israel lobby on Wilson’s side, and labor unions, peace groups and rank-and-file Democrats on McCarthy’s.

McCarthy Trails in Polls

With less money and without a burning issue, McCarthy has trailed in the polls throughout most of the campaign. Going into the final few days of the race, his challenge remains what it always has been--to give voters a compelling reason to vote against Wilson, a flexible conservative who has worked hard to broaden his base of support.

Often accompanying Democratic presidential candidate Michael A. Dukakis, McCarthy echoes Dukakis’ rhetoric about the needs of working families as he tries to appeal to middle-class voters.

Traveling up and down the state, the 58-year-old McCarthy leans on the one message he thinks can win for him. He brands Wilson a pawn of corporate interests, “a senator for them” and himself as the “senator for us,” a champion of “go-to-work-every-day” Californians.

As Election Day draws near, McCarthy has been attending a series of rallies that are part of California Democrats’ $4.5-million voter turnout campaign. McCarthy has pegged his hopes for victory on the massive drive, which has targeted more than 700,000 voters who might not otherwise cast their ballots for McCarthy or Dukakis.

Could Give a Boost

Democratic Sen. Alan Cranston, a McCarthy booster, said the voter mobilization could give McCarthy a 7-percentage-point boost. But going into the weekend, polls indicated that McCarthy was trailing by as much as 14%.

McCarthy, upbeat despite the polls, hit the road Saturday for a hectic day of campaigning in the larger Northern California cities of San Jose, Oakland, San Francisco, Richmond, Vallejo and Sacramento.

He repeatedly told spirited get-out-the-vote rallies that the polls are wrong.

“I always get a little suspicious when there are more pollsters than registered voters,” said McCarthy, frequently invoking the name of the late U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in an appeal to the idealism of his Democratic audiences.

Wilson is finishing up his campaign traveling from the Central Valley to the coast to Orange County and north again. He is touching base with farmers and environmentalists, Jews, old people, veterans and defense contractors--all elements of a diverse constituency he hopes to mobilize on Election Day.

With Wilson, the operative message is “making a difference for California.” He tells a group of Modesto growers that he is troubled by the huge subsidies propping up Midwestern corn and wheat and later reminds the same audience that he was responsible for legislation authorizing $200 million in federal money to promote the export of raisins, avocados and other California crops.

On the banks of the American River east of Sacramento, he boasts of his successful efforts to win wilderness-status protection for sections of four rivers in the state. The same day, he tells a group of elderly recreational vehicle owners of his opposition to another wilderness bill that limits motor access to the Mojave Desert.

In Orange County, the crucible of California conservatism, Wilson talks tough about national defense and crime.

“I don’t believe we should entrust our security to the United Nations or the safety of our streets to the ACLU,” he told an enthusiastic GOP rally Saturday.

But even in Orange County, there were a few signs of disapproval.

“I was hungry and you fed me nuclear weapons,” read one placard, held aloft by members of a group calling itself “Peace Politics” of Santa Ana.

The Senate campaign has grown from a desultory skirmish, with few public appearances by either man, into something of a vendetta. Passing acquaintances in the state Legislature where both got their start in state politics in the late 1960s, Wilson and McCarthy have come to dislike each other.

Portrayed as Political Pygmy

These days, McCarthy looks for ways to portray Wilson as a political Pygmy, while Wilson accuses his opponent of character assassination and likens his tactics to the McCarthyism of the 1950s.

But the Wilson and McCarthy campaigns are alike in one respect. Each has sought to stake out the middle ground in this year’s election.

During the last year, Wilson introduced two bills on child care and health care, two issues with which he has not been associated in the past. McCarthy, a one-time advocate of a nuclear freeze, has softened his criticism of the controversial Strategic Defense Initiative. In campaign commercials, he has trumpeted his support for the death penalty, which he once opposed.

However, the candidate’s overall records make it clear that Wilson, despite notable exceptions, is still a conservative and McCarthy is a liberal.

Elected to the Senate in 1982, the 54-year-old Wilson is regarded as a dogged infighter for President Reagan’s defense buildup, for legislation escalating the war on drugs, and for bills beneficial to a broad spectrum of California businesses. Close to the White House most of the time, Wilson also has come to be known as a bit of a maverick. He has opposed the Administration’s efforts to expand offshore drilling along the California coast. He has departed from the conservative line on abortion and, occasionally, on civil rights.

Campaigning, Wilson has referred to himself as a “compassionate conservative.” He stresses his record on crime, particularly his co-sponsorship of legislation authorizing a federal death penalty for drug racketeers, and he talks a lot about his most notable environmental achievements, battling offshore drilling and co-sponsoring a 1984 bill granting wilderness status to 1.8 million acres of California timberland.

Served in Marine Corps

The son of a St. Louis advertising executive, Wilson attended private schools, graduating from Yale in 1955. He served as an officer in the Marine Corps and later received a law degree from UC Berkeley. Besides serving in the state Assembly, Wilson was mayor of San Diego from 1971 through 1982.

Born in New Zealand and reared during the Depression in San Francisco’s working-class Mission District, McCarthy has frequently touched on his roots as he campaigns. He talks of close-knit neighborhoods, of families struggling to make ends meet and of old people left without assistance. His firm moral training in Catholic school and a family upbringing that stressed helping others has shaped a political bent in favor of traditional Democratic constituents, the urban poor, union members and old people.

A one-time seminary student, McCarthy was at loose ends until he joined the Air Force Reserve during the Korean War. He eventually enrolled at the University of San Francisco and later received a law degree from San Francisco Law School. His political career began with his 1963 election to the city’s Board of Supervisors. Five years later, his 20-year career in state government began with his election to the State Assembly. He was chosen Speaker of the Assembly in 1974 and won the first of two races for lieutenant governor in 1982.

It was primarily during his six years as Assembly Speaker that McCarthy developed his reputation as a liberal reformer--a reputation that was once a political asset. Now, in a year when the term “liberal” has become a virtual four-letter word, McCarthy is trying to fine-tune that reputation as he stumps for middle-class votes.

Agenda Remains Popular

Still, much of the agenda McCarthy carried when he was in the Legislature remains popular among Californians, and he can freely boast of many of his accomplishments--protecting the state’s coastline from massive development, supporting increased aid to the elderly and helping the children of migrant farm workers get better educations.

In the waning days of the campaign, McCarthy has been able to shift the focus of the race to some of the issues he knows best--the environment, health care for the elderly and child care. In each of those areas, he bangs away at Wilson’s record and argues that he would be a stronger advocate. Among organized groups, he has met with success, garnering more endorsements than Wilson.

But even Democrats say that, to win the election, McCarthy must do more. He must dispel the widespread perception that Wilson has been at least adequate on domestic issues. In a year when people are more bored than angry with the political status quo, McCarthy, observers say, must light a fire under a race that is barely smoldering.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.