U.S. to Expand Right to Learn of Job Hazards

WASHINGTON — Under court order, the Labor Department will vastly expand the federal “right to know” worker safety law today, allowing an additional 59 million U.S. employees to demand information from their employers about hazardous chemicals in the workplace, The Times learned Tuesday.

The department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration will include virtually all private-sector workers under the law, which has been restricted to about 14 million manufacturing employees until now. The move was made in response to a federal appeals court order to expand the scope of the law, formally titled the Hazard Communication Standard.

Training Programs

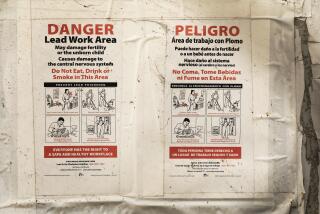

Expansion of the standard requires thousands of non-manufacturing employers to establish hazard communications programs that will provide information to their employees through labels on containers, written materials and training programs.

“This is a very important action in reducing injuries and illnesses due to chemical exposures,” said a Labor Department official who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Giving workers the right to know in all work sites is a real milestone in safety and health.”

Margaret Seminario, an AFL-CIO health and safety expert, agreed that the action carries major significance, noting that a federal study indicated that one of every four workers in the country is exposed on the job to some substance that can cause death or serious disease.

She said that those working in construction, hospitals and a number of other settings would be better protected as a result of the change.

“This is a major action,” Seminario said. “It fills the gap on what we’ve been trying to do in ‘right to know.’ This is something we have been fighting for since 1973. It’s taken the action of a court and the threat of contempt to get OSHA to act.”

Labor and public health advocates began to demand greater access to information about hazardous substances from employers in the 1970s. Seminario said that this push took place as thousands of new chemicals that most workers knew little about were coming into use.

One study by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health showed that, in 5,200 plants surveyed, workers were exposed to 95,000 trade-name substances. At 90% of the plants, neither workers nor employers knew what chemicals were contained in the trade-name products.

In OSHA’s 16-year history, the agency has set standards limiting exposure to only 15 hazardous chemicals. A Labor Department source said the agency has been unable to study most of the hundreds of thousands of others used in the workplace and that the process of setting standards for those it has studied has been slow.

Both the Labor Department source and Seminario said that the lack of standards on the use of thousands of chemicals underscores how important it is for workers to be able to get information on them.

OSHA first proposed a “right to know” standard in 1981 at the end of the Jimmy Carter Administration. But, soon after President Reagan came into office, the proposal was withdrawn. Chemical manufacturers and a variety of other employers had asserted that the law was unnecessary.

States Enact Laws

Cities and states began to enact their own laws in response to demands from union and community activists who were concerned about hazards in the workplace and chemical spills with broad impacts on communities.

OSHA proposed a new hazard communication standard in 1982 but limited it to manufacturing workers. The standard was formally adopted in November, 1983. Early in 1984, the United Steelworkers of America and other labor unions sued the agency in federal court in Philadelphia in an attempt to broaden and strengthen the standard.

In May, 1985, the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the unions’ suit and ordered OSHA to expand the standard to include non-manufacturing employees unless the agency could demonstrate that it was not feasible to do so.

The court ruled also that OSHA must limit the kind of information that an employer may withhold from workers on the ground that it was a trade secret. OSHA soon changed its definition of a trade secret.

But the agency moved slowly on the issue of expanding the standard. In January, the unions returned to court seeking a contempt order. On May 29, the 3rd Circuit Court reaffirmed its earlier decision and gave OSHA 60 days to extend the Hazard Communication Standard to non-manufacturing workers.

In late June, the Labor Department asked the court for a rehearing, contending that the appellate court ruling conflicted with an earlier Supreme Court decision on procedures OSHA had to follow in setting safety and health standards. That request was denied last Friday.

Late Tuesday, a Labor Department source said the new standard would be formally posted in the Federal Register today. He refused to comment when asked if this meant that the department had abandoned the possibility of appealing the appellate decision to the Supreme Court.

“We have issued the final rule to be in compliance with the (appellate) court order,” he said, adding that the agency had planned to take this action regardless of a court order “by late 1987 or early 1988.”

The source said that the agency would leave the record open for 60 days’ further public comment on the issue of whether the expansion of the standard would reduce risks to workers.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.