Column: Bowing to business and the right wing, the SEC issues a pathetically watered-down climate disclosure rule

- Share via

Corporate managements nationwide undoubtedly breathed sighs of relief Wednesday, when the Securities and Exchange Commission approved a rule mandating their disclosures of greenhouse gas emissions and risks from global warming.

That’s because the rule is much weaker than its original version, which was first published in March 2022. The final version removed provisions requiring disclosure of some emissions produced by a company’s entire business chain and expanded exemptions for smaller companies.

But if managements think they’ll be able to avoid making more complete disclosures than the SEC is requiring, they have another think coming.

Far more investors are making investment decisions that are informed by climate risk, and far more companies are making disclosures about climate risk.

— SEC Chairman Gary Gensler

Shareholders are demanding more. So is the European Union, which has enacted rules requiring all companies with EU branches employing more than 250 workers, more than $42 million in European revenues or more than $21 million in capital assets to make the very disclosures that the SEC dropped from its mandate, starting in 2025.

More than 3,200 U.S. corporations are expected to become subject to the EU mandate.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Then there’s California, which last year enacted two laws requiring companies with annual revenues of more than $500 million and business activities in the state to disclose their climate-related economic risks; companies with revenues of more than $1 billion face more stringent requirements to report the full range of their emissions, similar to the EU mandate.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and several other business lobbying groups have already filed a federal lawsuit to overturn the California law, in which they estimate that the laws will cover 10,000 companies. (Rule of thumb: If the Chamber of Commerce is on one side of a lawsuit, you can rarely go wrong in assuming the public interest is on the other side.)

In any event, the laws have the support of numerous corporations with headquarters or sizable business interests in California, including Microsoft and Apple.

“We know that consistent, comparable, and reliable emissions data at scale is necessary to fully assess the global economy’s risk exposure and to navigate the path to a net-zero future,” Microsoft and 14 other businesses wrote in an Aug. 14 letter to state legislative leaders.

The state’s legislation, they wrote, “would break new ground on ambitious climate policy and would allow the largest economic actors to fully understand and mitigate their harmful greenhouse gas emissions.”

Blindly protecting investments in coal and oil without taking account of the changing world is a formula for impoverishment — environmentally, socially, and especially financially.

Meanwhile, 10 states with Republican political leaderships have signaled that they will sue to invalidate the SEC initiative, on the claim that the rule “exceeds the agency’s statutory authority.”

All this does more than hint at the headwinds the SEC faced in crafting its final disclosure rule. These included objections from many in the business community and conservative politicians pursuing their fatuous campaigns against ESG policies — environmental, social and governance — of corporations and investment firms.

The SEC’s Democratic majority, led by its chairman, Gary Gensler, also plainly harbored concerns about how its more expansive rule proposal might fare with a conservative federal judiciary, including a Supreme Court that seems to be searching for grounds to pare back the reach of federal regulatory agencies, if not invalidate their authority altogether.

Gensler observed after the commission vote that its goal was to provide for consistency in how companies report information that most are already compiling.

“Far more investors are making investment decisions that are informed by climate risk, and far more companies are making disclosures about climate risk,” he said. He didn’t specifically defend the SEC’s weakening of its initial proposal, except to say that the plan was revised “based upon public feedback.”

Let’s take a closer look at the issues and the political context.

First, here’s what the SEC’s rule encompasses.

At its core are disclosures about emissions of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide — emissions that trap heat within the Earth’s atmosphere, driving global temperatures higher. Global warming produces major changes in climatological manifestations — more storms of greater severity, droughts, melting ice producing a rise in sea levels, and so on.

Emissions fall into three general categories. Scope 1 emissions are those a company produces directly, say from its delivery trucks, boilers, refineries, manufacturing plants. Scope 2 emissions are those it produces indirectly, for example, from the power plants from which it purchases its electricity.

Scope 3 emissions are the most contentious. They’re produced by a company’s vendors when it orders supplies and consumers when they use its products. In general this is the largest category, accounting for 70% of total emissions for many businesses and as much as 90% for some. But they can be hard to define, calculate and manage.

Corporations of all kinds are getting an earful from shareholders and the SEC about the need to disclose climate change impacts.

The SEC originally contemplated requiring disclosures of all three categories. The final rule removed the Scope 3 reporting requirement entirely, and mandates reporting of Scope 1 and 2 emissions only when they have or are likely to have “a material impact on the registrant’s business strategy, results of operations, or financial condition.”

Those changes gratified some business organizations and their henchpersons in Congress, but disturbed environmental groups. Removing Scope 3 disclosures, said Danielle Fugere, president of the Berkeley-based environmental organization As You Sow, “creates a significant hole in shareholders’ understanding of climate risk.”

The fact is that full disclosure of these risks is something that regulators around the world, as well as shareholders and investors, have been demanding for years. Who’s against it? Head-in-the-sand Republicans and right-wing culture warriors, that’s who.

Hester Peirce, one of the two Republicans on the SEC, carried their ball into its meeting room. Weak as the final rule is, she wasn’t satisfied. As enacted, she groused in a statement Wednesday, the rule “still promises to spam investors with details about the Commission’s pet topic of the day — climate.”

That dismissal of global warming, an elemental threat to life on Earth, as a “pet topic” should tell you how fundamentally unserious GOP policymakers are about their responsibilities.

The anti-ESG cabal among state-level Republicans appears determined to undermine the interests of their own constituents, all for the sake of “owning the libs.”

Consider three states that have been among the leaders in banning investment firms from doing business with their governments because of the firms’ support for environmental policies: Texas, Florida and Louisiana.

Those are the three states that have led the nation in cumulative damage costs due to climate-related disasters from 1980 through 2022 — racking up expenses of $380 billion, $370 billion and $290 billion, respectively.

Chevron’s directive from shareholders: Report how you’re lobbying against the environment.

The general approach of disclosure critics has two threads. One is to pretend that the effects of global warming are irrelevant to the operations and the future of most businesses. The other is to assert that they’re too nebulous to calculate or, alternatively, that performing the calculations is just too burdensome.

Neither argument holds water.

I reported in 2021 that shareholders were already asking for more disclosures from managements about how their activities contribute to climate change, and more about how climate change will affect their destinies.

Fossil fuel companies weren’t the only targets of shareholder resolutions on these topics — they also appeared on the agendas of annual meetings of manufacturers, retailers, banks and many others.

In 2023, shareholder resolutions demanding climate and environmental disclosures dominated the proxy season with 146 filed, according to the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, which tracks ESG issues. Many won plurality support, but more than half dealing with climate were withdrawn after managements made commitments to their sponsors to meet their disclosure goals.

Investment watchdogs are on the case. Fitch Ratings, which analyzes corporate creditworthiness, says that as many as 20% of the 1,650 corporations it studied might face ratings downgrades due to their “climate vulnerabilities if such risks are not mitigated” by 2035. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm, has said it’s not backing off from pushing corporations to disclose how they address climate-related risks.

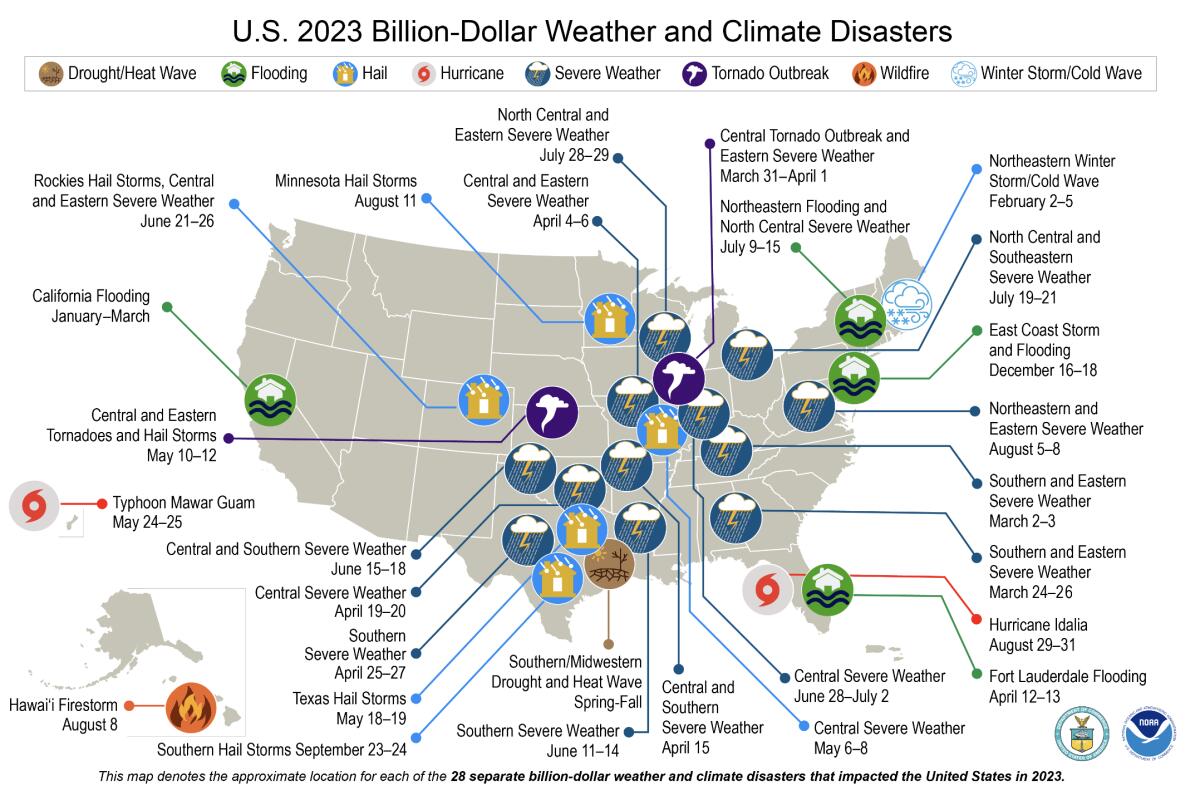

The U.S. government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration identified 28 weather- and climate-related disasters costing $1 billion or more in 2023, including a drought, four floods, 22 severe storms and a wildfire.

That was the highest number recorded since NOAA began taking count in 1980 and the ninth consecutive year in which 10 or more billion-dollar weather or climate disasters struck the U.S.

NOAA’s initial estimate is that the 2023 disasters cost more than $90 billion, but it’s certain to rise, since the ultimate price tag of the 18 disasters reported in 2022 came to more than $165 billion. The disasters took 492 lives.

To put it another way, any management of a large business in the U.S. that thinks it can evade the costs of global warming is living in a dream world.

Global warming deniers in business and politics persist in treating the climate crisis as merely a ginned-up topic of debate. That’s the gist of the business lobby’s lawsuit over the California laws.

The lawsuit treats the laws, bizarrely, as infringements on companies’ 1st Amendment rights. The state, the plaintiffs assert, is forcing “thousands of companies to engage in controversial speech that they do not wish to make” — speech they say is “political, and thus controversial.”

How a leading global warming scientist won $1 million from right-wing climate change deniers -- and gave heart to foes of pseudoscience everywhere.

This is absurd on its face — tantamount to Donald Trump’s claim that by urging his followers to march to the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, he was just exercising his right to free speech.

This would allow any mandated disclosure to be reduced to a free-speech violation — after all, any such disclosure must be expressed as a series of words.

The courts, including the Supreme Court, have generally rejected assertions that mandated disclosures violate the 1st Amendment when the disclosures serve a legitimate government interest, such as protecting investors from fraudulent claims, or providing investors with important information — for example, the level of emissions by a public corporation or its potential exposure to global warming.

In this case, the business lobbies stretch to the breaking point their description of the state’s mandated emission disclosures as mere speech. They also assert that the state’s purpose is merely to “fuel pressure campaigns against business.”

They can’t make that claim stick with a straight face, so they misrepresent the laws. Here’s how they quote a state Senate analysis of one of the statutes: “‘For companies, the knowledge’ that their compelled statements ‘will be publicly available might encourage them to take meaningful steps’ to support the policy goals of the state.”

That’s a flagrant misquotation. Here’s what the analysis actually said: “For companies, the knowledge that their emissions will be publicly available might encourage them to take meaningful steps to reduce GHG emissions.” The words and phrases that the plaintiffs replaced with their own tendentious language are in italics.

It’s not the “compelled statements” that will be publicly available, but the actual level of their emissions. If the result is “pressure campaigns” aimed at prompting the companies to be cleaner, what’s wrong with that?

As for the state’s “policy goals,” the laws aren’t aimed at supporting a goal cherished by the liberal legislators of California, as the plaintiffs want you to think, but the national and international goal of reducing greenhouse gases.

None of this is to say that the Chamber of Commerce and its fellow lobbies won’t prevail in court. But it’s proper to note that when the best arguments they muster are based on lies and misrepresentations, they might not have many other arrows in their quiver.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.