They were born in Colombia. Their parents fled Venezuela. They are citizens of nowhere

- Share via

Reporting from Bogota, Colombia — In the fall of 2017, as Venezuela was imploding, state intelligence agents came looking for Belys Torrealba Tovar, who had helped recruit young people to protest against the government of Nicolas Maduro. She went into hiding for two weeks, then fled to neighboring Colombia.

A year and a half later, she gave birth to a boy at a hospital in south Bogota.

At 5 pounds, 8 ounces, he was tiny but healthy, with a round face and a crop of black hair. She named him Angel.

Now just over a month old, he is stateless, a citizen of nowhere.

Unlike the United States and most countries in Latin America, Colombia does not automatically grant citizenship to anybody born there. And though he does qualify for Venezuelan citizenship, claiming it would require his mother to return to the country or pay a visit to one of its embassies or consulates. There are no longer any in Colombia.

“I just want him to have a nationality so that he doesn’t end up essentially not existing in the world,” the 24-year-old Torrealba said.

Thousands of children are in the same situation amid one of the largest forced displacements in modern history, as an estimated 5,000 people flee Venezuela each day. Nearly 4 million have already left, more than a quarter of them to Colombia, which offers them temporary visas.

Colombia’s civil registry agency counts nearly 3,400 children born to Venezuelan parents since October 2017, when the government started tracking them. Advocates say the total could be as high as 25,000.

Children born without Colombian citizenship are allowed to enroll in school and the public healthcare system. Though many benefits of citizenship — voting, owning property or getting married — wouldn’t be considerations for years, statelessness only adds to the angst of uprooted families.

“They are children who don’t have a state to protect them,” said Venezuelan lawyer Xiomara Rauseo. “Practically orphans.”

It’s no surprise why so many people are leaving Venezuela.

Once Latin America’s richest country, citizens watched its economy collapse spectacularly as oil prices fell, hyperinflation rendered the currency worthless and shortages of food and medicine led to rampant hunger and disease.

One study showed that by 2017 nearly 90% of Venezuelans were living in poverty and that the average citizen had lost 24 pounds — figures that are surely higher now.

In Colombia, Torrealba struggled to rebuild her life. After a month of sharing a crowded apartment with several other migrants from Venezuela, she found a job as a hotel maid and moved into her own room in an apartment across town.

She started dating a man from Venezuela and in September found out she was pregnant. He appeared ecstatic at first but soon he got a job almost 300 miles from Bogota and stopped responding to her messages.

Torrealba would endure the rest of the pregnancy alone.

She understood that children born in Colombia qualified for citizenship there only if at least one parent was Colombian or has legal permanent residency. New mothers before her had posted warnings on Facebook about it.

As a result, she thought about returning to Venezuela to give birth.

But in February, the Venezuelan government cut diplomatic ties with Colombia and closed border crossings amid a U.S.-backed effort to bring in humanitarian aid, which Maduro saw as a pretext for a U.S. invasion. When the country was hit with a series of massive blackouts, Torrealba decided to stay put in Colombia.

She was glad she did, because she developed high blood pressure and a condition called preeclampsia, which can lead to fatal complications, and had to be hospitalized. She had heard that mothers and babies were dying in maternity wards back home in Venezuela and worried about how she and Angel would have fared there.

Early last month four days after giving birth, Torrealba was recovering at Hospital Materno Infantil, a public maternity ward where expectant mothers sleep six to a room on beds with aged metal frames, their names written on dry erase boards above their pillows.

A nurse came in to take her blood pressure and gasped at the results. “Dear girl, what are we going to do?” she said affectionately.

About 15 babies are born at the hospital each day, roughly a third of them to Venezuelan mothers, many of whom learn of the citizenship predicament only after they deliver.

Juberkis Alvarez Guanipa said a social worker had informed her that morning that her newborn daughter wasn’t Colombian. But the 19-year-old hadn’t been told about the impediments to getting her Venezuelan citizenship.

“I didn’t know,” she said in a near whisper. “I don’t even want to think about it.”

Colombian leaders say they’re doing everything they can to help Venezuelans.

“We aren’t responsible for statelessness — it’s Venezuela that didn’t want to give them the documents,” said Felipe Muñoz, an advisor to the Colombian president. “Colombia has exercised generosity and historic responsibility to help the Venezuelans. Here the discussion isn’t what to do but how to do it better.”

Migration officials announced in early May that they are studying whether the constitution would allow them to grant citizenship to children born to Venezuelan parents.

Multiple citizenship proposals also have been presented at the congressional level. Last month, a commission approved a bill for initial debate before the Senate.

Sen. Andres Garcia Zuccardi, who authored two other bills aiming to provide Venezuelans with Colombian citizenship, said his greatest concern is that thousands of children could grow up without access to higher education, healthcare or formal work.

“This situation not only means the violation of fundamental rights,” he said, “but it also affects the social, economic and future dynamics of a country that could be built with a significant number of people without legal status and without opportunities.”

Even before diplomatic relations plummeted and the consulates closed, it was difficult for Venezuelan parents to get their Colombian-born children citizenship.

“The baby is a foreigner,” a nurse in Bogota told 23-year-old Kimberlyn Suarez Villegas after her son Estheban was born in November 2017.

At the Venezuelan Consulate, officials left her waiting indefinitely.

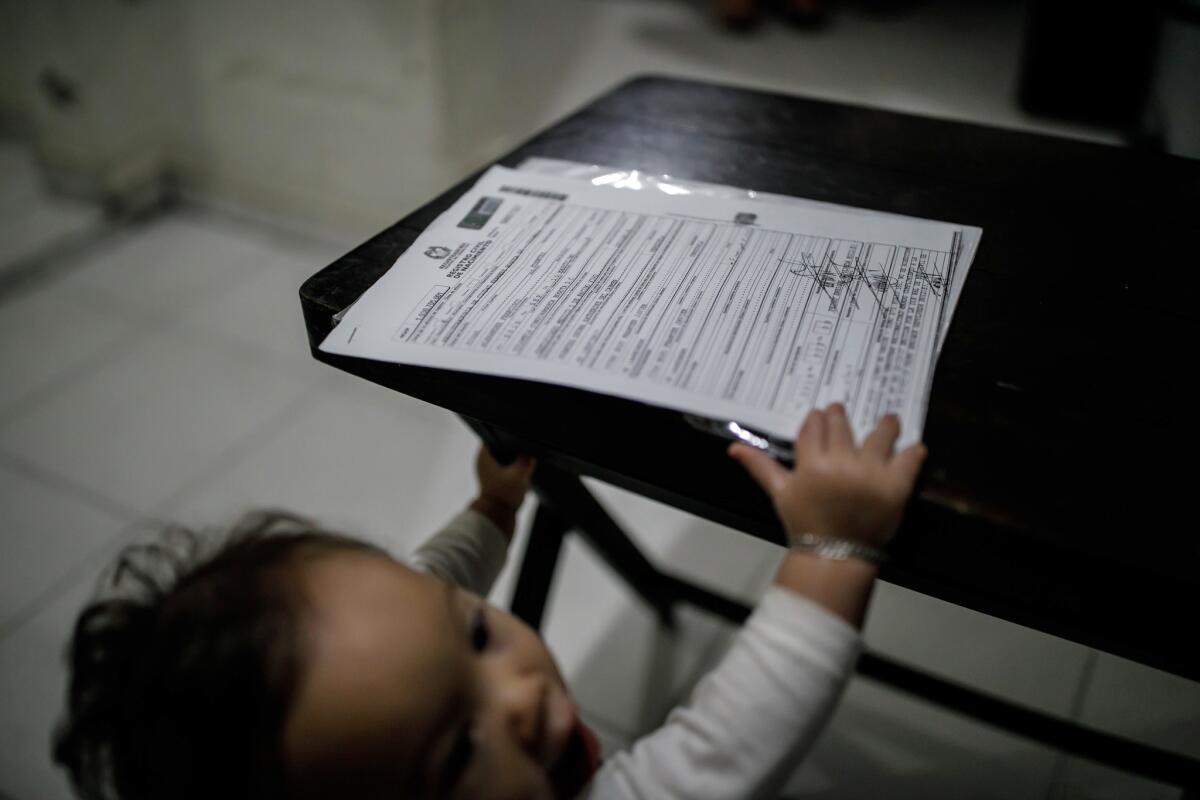

She did manage to get a birth certificate from the Colombian civil registry office. On one side are his tiny footprints in black ink.

On the other is a note: “Not valid for citizenship.”

Suarez, who was close to finishing her law degree when she and her husband left Venezuela nearly four years ago, said she has little faith that the Colombian president, Ivan Duque, or his government will grant citizenship to children like her son.

“People see us as invaders,” she said, bursting into tears. “My son is a stateless baby to Maduro’s government because I betrayed my country the moment I came here. And to Duque’s government he is also a stateless baby because his mother came here.”

Suarez’s dreams for her son are simple: “What I want is for my son to have a citizenship document so he isn’t disadvantaged in the future. That he live well, and be able to do normal things like a normal person — that’s it.”

As for Torrealba, she has settled into motherhood in her new home. Her mother left Venezuela and moved to Bogota just before the baby’s birth. They both found new jobs, Torrealba at a public relations firm doing graphic design and her mother as a seamstress.

Torrealba recently devised a plan to give Angel citizenship. Over Christmas, she’ll return to Venezuela with her mother and son to register him. She’ll do it somewhere other than Lara, where her family lives, and they’ll stay no longer than two weeks.

“If I enter Venezuela and they find out I’m there, they could put me in jail, kill me or disappear me,” she said.

But if the plan works, her baby will be a Venezuelan citizen by next year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.