- Share via

ESPAÑOLA, N.M. — The caretaker at the hillside cemetery braced against the cold and walked among the graves. Crosses cast shadows on bunched flowers. A strand of tinsel gleamed from a bare tree. He looked over the rows and shut the gate, his face red, his hands small and coarse.

“I’ve got to come back and pick up the garbage,” the caretaker said. “People leave it.”

He glanced at a visitor, anticipating the question.

“We had a few kids who overdosed,” he said, nodding toward the graves. “But none for a little while.”

He got into his truck and headed west into Española where a familiar scene unfolded.

Shoppers and workers drove past addicts roaming Riverside Drive, the main drag in this town of 10,500. Kids played in trailer parks. Contractors loaded pickups. Cars came and went from a methadone clinic. Men wearing hoodies and expectant gazes drifted toward a house with barred windows. They rustled pockets for cash. Others headed toward the marshes on the city’s fringes, where, as the morning frost lifted, Cristian Madrid-Estrada, a bearded man of 23, sat with a gun holstered on his hip at the Española Pathways Shelter.

“You can’t believe it sometimes,” said Madrid-Estrada, the homeless shelter’s chief executive officer. “I was here last night when my fiancee called and told me someone was trying to break into our house. He was at the windows.”

Madrid-Estrada spends much of his time at the shelter, giving addicts beds and warmth on frigid nights. But like others in this city, he contends with burglaries, robberies and thefts carried out by fentanyl addicts desperate to fuel their next high. The state police and the county sheriff have been called in to help Española’s understaffed Police Department, which reported 224 burglary calls last year, up from from 155 in 2020.

Rallying voices are trying to fix this community under siege. But it’s unclear if the story of Española, where a quarter of the population is poor and the murals of the dead are painted on junction boxes, will be a narrative about how to save a town from addiction — or lose it. In a one-year period ending in June 2022, Rio Arriba County reported 50 fatal overdoses, giving it the highest rate in New Mexico. It was about four times the national rate of approximately 33 per 100,000.

Española is a troubling American tale. Its despair and suffering echo through cities large and small, from the pitched tents and open drug use in Los Angeles to the hamlets and hollows reeling from the opioid epidemic across Appalachia. The crisis is born from a decades-long misguided war on drugs, greed in the pharmaceutical industry, an ill-equipped prison system, failed treatment programs and a nation seemingly inured to the startling toll of addiction.

Sitting amid tribal lands straddling the Rio Grande, Española appears stranded between better known Santa Fe and Taos. More than a century ago, long before cartels trafficking fentanyl with nicknames like China White and Dance Fever crisscrossed New Mexico on Interstate 40 and Interstate 25, ranchers and farmers here loaded their wares on trains bound north and south in what was known as the Chili Line. That route ended decades ago; other small businesses and industries disappeared as well.

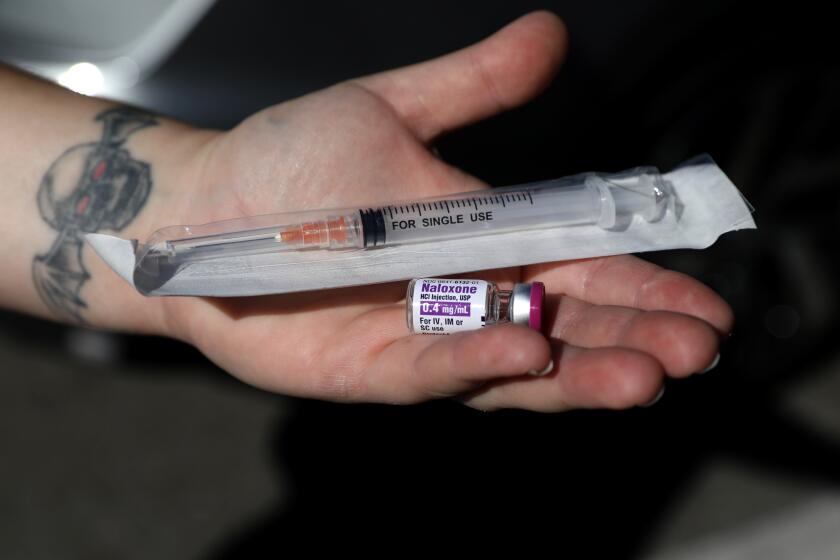

Drug addiction seeped into the Española Valley after the Vietnam War as heroin, cocaine and other drugs flowed in from Mexico. Heroin settled in hard for years, tearing through families, ravaging livelihoods and scattering lean-tos and broken men beneath bridges. But over the last two years, the market has been taken over by fentanyl, which is cut with other substances and at times is so potent that it can take at least two doses of Narcan to revive an overdose victim.

The state and L.A. County have worked hard to make Naloxone more widely available. One of the hurdles, though, has been the price of the inhalable version, Narcan.

“I’ve had knives pointed at me. Pipes swung at me,” said Madrid-Estrada. “It’s insane how much has changed in the last year. It’s scary. We have generational drug use. Generational trauma. Half the kids I went to school with didn’t have parents. They were dead or in jail or gone.” But fentanyl, he added, “is a completely different animal. A whole new epidemic no one was prepared for.”

The town — which has drawn addicts and the homeless from other states — has too few detox and drug treatment centers. Grandparents are raising grandchildren, and a “baby box” has been built at the fire station to take in unwanted infants. Shoplifters haunt the aisles at Lowe’s and Walmart. Syringes for heroin that once littered sidewalks and riverbanks have often been replaced by glints of tin foil used for smoking fentanyl.

“We don’t even really see heroin overdoses in New Mexico anymore,” said Miranda Lopez, the state’s public health analyst for the national Overdose Response Strategy. “Fentanyl has changed things in ways that are unimaginable. It’s evolving with so many novel substances coming into play. You’re constantly having to reevaluate.”

Chris Dewitt, a resident at Española Pathways Village, a converted motel the shelter has turned into transitional housing for recovering addicts, spoke of the disarray that had gripped him for years and led from heroin to meth to fentanyl: “I tried fentanyl. It made me sick. It hit different. Much stronger. I tried it again. I wanted to embrace the darkness,” he said.

“I was the monster. It took me a while to see myself as worth saving.”

Much of the addiction stems from family problems, including domestic violence and abuse, said Nicko Zamora, who used drugs for more than 40 years and now works to help addicts recover. “A lot of us got sick on our secrets,” he said. “Drugs were the Band-Aid. It goes with our heritage in a weird, crazy way. We’ve seen it happen to Great-Grandpa, Grandpa, Dad and all the uncles. Drug use became normal.”

Madrid-Estrada and Pathways co-founders Ralph Martinez and former state Rep. Roger Montoya are working to change things. Martinez and Montoya helped get a $1.8-million grant for the property that houses the shelter, a Goodwill, a wellness center and a food pantry. John Ramon Vigil, at 27 the youngest mayor in New Mexico, is proposing the state open a regional drug treatment center. And Jeramay Martinez, who sued OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, is raising the 4-year-old son of a fentanyl addict and plans to start an agency to help addicted mothers and children exposed to drugs in the womb.

Madrid-Estrada often wonders, though, about the town’s fate. He estimates there are between 250 and 350 homeless people in the Española Valley, some wandering past scrap yards and cannabis shops, not far from the ancient cave dwellings of Native American spirit lands, emerging from the cold darkness and into the shelter’s dim porch light.

On a February night, with the temperature slipping below freezing, a row of men and women huddled beneath blankets like an army dispersed. They waited to check in at the shelter, where they would receive a bowl of chili, a shower and a bunk bed. They could watch “Blazing Saddles” or “The Karate Kid” or play Battleship or put together 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzles. In a common room, Roberta Walker, a 47-year-old mother of seven, wept, yelled and calmed, as if a sudden storm had swept through her.

“I did crack for six years, meth for two and then to opioids and now fentanyl. I’m actively using because that’s what I want to do,” she said. “I don’t know who I am sometimes. I’ve never been Black enough, Latina enough or white enough. I’m mixed. But I’ve got to find me. Who am I? I’m always fighting that anger. I’m a Christian. I’m an addict.”

Ralph Martinez was once a man under a bridge, sleeping on the dirt, shooting heroin into a neck vein, listening to men with liquor bottles murmuring around barrel fires in the night.

He sat the other day in a hamburger joint on Riverside Drive, sipping a soda and planning events to raise money. His tattoos were the same — stars, a heart and daughters’ names scrolling up arms — but he was far from the man he was when he stole an Xbox from kids and jacked circular saws from Lowe’s to sell for drug money.

“The deeper I got, the deeper I went,” said Martinez, 45, who was homeless from 2006 to 2012, had five felony convictions and went through six rehabs before he got clean. “I lived under a hoodie and went months without changing underwear. I held people in my arms who OD’d and died. But fentanyl has made things different. The homeless population today is thicker, and no one cares about being seen in town. Before, you’d hide in the shadows of the night, take the back pathways. People had pride.”

He now works as a government affairs specialist at Los Alamos National Laboratory. He sits on community boards and drives around Española, trying to fix the blight, like the abandoned shopping carts left outside a boarded-up low-income apartment building. He said the city, which has a $12-million budget and not enough money coming in from a state that is one of the poorest in the country, needs to reduce the homeless and addicted populations by working more closely with churches and institutions like Pathways.

“The message our leaders want to put out to their constituents is that they have it under control,” he said. “They certainly don’t have it under control.”

He told a story about why homelessness appears intractable: The city manager asked for Martinez’s help in cleaning up an encampment behind an ice cream shop. Another enclave had been bulldozed and the city wanted to try a different approach. Martinez had attended elementary school with the “leader of the pack” at the encampment. The two met and worked out a system for trash collection and syringe retrieval. But the plan collapsed when the property owner — who had not stepped up earlier — demanded the city remove the encampment.

“The homeless are not going to just disappear,” said Martinez. “Where are they going to go?”

He drove over the bridge where he once lived. Parts of him, his past, the things he’d rather forget but doesn’t dare, appear like whispers, reminders. A young couple with tattered backpacks walked along the road, picking up half-smoked cigarettes in what homeless addicts call Easter egg hunts. The couple pressed on through the afternoon traffic as the sun shone on the snow of the distant Sangre de Cristo Mountains and winds blew across pueblo lands.

“You can’t go back in time and clean the generations that have already suffered,” he said. “But you can go in today and break that curse and stop it from infecting other generations. We have to figure out why addiction is prevalent here. If you don’t want any weeds in the ground, you have to pull them out by the roots.”

Mayor Vigil walked through Española’s historic downtown, a stretch of small businesses, abandoned buildings and murals of the Virgin Mary, low-rider cars and men planting fields. Vigil’s ancestors arrived in this valley 12 generations ago, and in 1939 his grandfather bought 2 acres and turned an old dance hall into a funeral business.

“This street’s seen better days,” said Vigil, the third member of his family to be mayor. “There was once so much life here. I’m hoping for a revival. We have a rich culture. We are the access point to the north. It’s always been a hub. Santa Fe is too Disney-fied. We’re a blue-collar real McCoy.”

Dressed in a blue blazer and jeans, a trimmed mustache on his young face, Vigil strolled toward Riverside Drive. He went to college and came back to Española when a lot of his contemporaries moved away. He pointed to paintings in Plaza de Española that depicted a legacy of Spanish explorers who arrived here in 1598 with nine Franciscan priests, which led to immigration, churches and a pueblo revolt.

The surge in fentanyl addiction and homelessness is testing his town, whose economy is largely reliant on those commuting about 17 miles away to jobs at the Los Alamos lab. Farming work shrunk over the years — loosening family bonds to the land and leaving a questioned sense of identity — and most other jobs are in retail and government.

Murders are not common in Española, but last year three of the city’s five homicides, including one on tribal land, were drug-related. Neighborhoods are turning ragged. Businesses complain about vagrancy and theft. An addict recently stabbed a store security guard. From 2021 to last year, shoplifting calls increased 21% from 693 to 837. In the same period, disorderly conduct calls jumped from 170 to 325.

The city’s new police chief, Mizel A. Garcia, was previously in charge of undercover units in Albuquerque, where he worked with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. But his Española department has only 26 of the 40 officers he says he needs. Its pay of $25 an hour for new officers can’t compete with higher wages in larger cities.

“Every city in the country is experiencing a fentanyl and homeless problem,” said Vigil. “But we’re a smaller town. We don’t have the resources that other communities do. Our budget’s extremely limited. We have a hard time just providing basic services.”

The problem is compounded by the overlapping jurisdictions — and competing interests — within the city. Española has parts of two tribes and two counties within its borders. “There’s a disconnect,” he said. “It’s hard getting everyone on the same page.” An example, he noted, is the difficulty of removing homeless people from tribal land in the city. Such a task would fall to tribal authorities, but they need assistance from the city to deal with nontribal people.

Vigil said another pressing concern is convincing the state to invest in a large drug treatment center for northern New Mexico. The city is expected to receive about $900,000 from statewide opioid settlements with a number of pharmacies, including CVS and Walmart. The mayor said the money will go to rehab programs and the Police Department. Local authorities, meanwhile, are putting together a team of firefighters, police officers, social and treatment workers and others to counsel and aid drug users to prevent overdoses.

“We’re trying to be proactive so we can lower our number of calls,” said Assistant Fire Chief John Wickersham. “We go to the same people for overdoses over and over. We’ve set up a QR code so they can find resources.”

But ingrained ways are stubborn to change. The mayor, like many people here, spoke of the close family ties that enable users and prevent them from entering rehab. He said he’ll hear people say: “Not my son. I’m going to get him through it. I’m going to pray the addiction goes away.” He added, “Honestly, we have to be realistic. They need treatment services to get off their drugs.”

Family, faith and weathered crosses marking roadside fatalities are potent on these lands. When asked why he ran for office, Vigil said, “Since I was 6 or 7 years old I wanted to be mayor. ... I prayed to God and I said, ‘God if this is what you want for me, please open the door and show me the way.’”

Jeramay Martinez drives the streets searching for the mother of the 4-year-old boy she is raising. His name is Domonic. His mother was addicted to heroin and other opioids. His father died of a blood infection from intravenous drug use. Martinez knows where to look, but it’s hard to find a nomad who meanders roadsides and through abandoned buildings.

“I want Domonic’s mom to get it together,” said Martinez, who is the boy’s legal guardian. “I want her to be part of his life. But I can’t let her sleep in my house. You never know. She goes MIA. I see her on the road and pull over. The last time it was snowing. I gave her the jacket I had on.”

She paused and glimpsed the sky.

“I hate to answer the phone anymore,” she said. “It might be the call that she’s passed.”

She turned from the window and sipped her coffee. Martinez is 33. She wears fanned earrings, ripped jeans and boots. She moves with swift grace, and her eyes hold the fierceness of a woman who doesn’t abide small talk. She opened a file of court papers. She was a plaintiff in a suit on behalf of children born to opioid-addicted mothers against Purdue Pharma before the company filed for bankruptcy protection.

“We’re losing our families and our friends,” she said. “No one is listening. We have to talk about drugs, social issues, domestic violence. People I went to high school with have done oxy, heroin and fentanyl. They look 60. No teeth. Bodies deteriorating.”

Many families here keep an invisible map of addiction — lines leading to death, sometimes with sudden tragedy, other times with sad familiarity.

Martinez’s mother’s boyfriend was a heavy drinker. He was arrested for DUI, she said, and was going through withdrawal in jail when he got hooked on heroin. Two weeks after he finished serving his sentence, he OD’d in her mother’s house. Another line traces to Domonic’s grandmother, who couldn’t take him in because she already was caring for three of his father’s orphaned children. Two more lines lead to Martinez’s stepmother, who was prescribed OxyContin after a car accident and is now on fentanyl, and to her cousin, an addict who recently bore her second baby.

Troubled histories twist and turn in her telling. Domonic was exposed to drugs in utero and was diagnosed with neonatal abstinence syndrome. A report from New Mexico’s Children, Youth and Families Department shortly after his birth reads: “Son born positive for heroin. ... will be discharged today; mom admitted to using heroin throughout pregnancy & was high when [she] went to hospital.”

Domonic has had massage, physical and speech therapy. He’s in preschool and doing well, but sometimes he gets agitated and hyperactive at night. “He has meltdowns.” Martinez reached for her phone. She scrolled the cracked screen and pulled up the website for Brigid’s Path, an organization in Kettering, Ohio, that helps drug-addicted mothers and their newborn babies.

“I want to do this here. We need more support groups,” she said. “I’m getting a license to become a certified foster parent. I’m working with caseworkers. I want to start a nonprofit. We have to take away the stigma from these moms. We can’t make them feel less.”

Cristian Madrid-Estrada walked out of the Pathways Shelter and through the parking lot. A casino run by the Santa Clara Pueblo rose in the short distance to his left. To his right, colors bloomed in the marshes, the tents of homeless people. He guessed there were dozens living amid the muck and reeds. No one wanders too far back there. A tree exploded into fire one night.

Madrid-Estrada was homeless for a spell when he was a child. He was 3 when his father, an addict at the time, kicked him, his mother and 4-year-old brother out of the house. They spent six months at a shelter for battered women: “That time is burned into my mind,” he said. “My mom was so strong, doing everything for us. That inspired me to do this kind of work.”

The Pathways Shelter — an old chiropractor’s office — sleeps about 30 people and last year served about 17,000 meals. Most of those who come are drug users. The shelter’s staff, some of whom are recovering addicts, is accustomed to reviving overdose victims with Narcan. The shelter forbids drug use inside, which means many fentanyl addicts, who need frequent fixes, will stay outside the shelter even in the snow rather than go through a night without using.

“Their behavior is aggressive and erratic,” said Madrid-Estrada. “You just don’t know.”

Pathways follows a holistic approach: It does its own case management on clients and has begun a pilot project to access Medicaid through collaboration with other agencies. “We started with nothing,” he said. “We’re now in sprint mode.” The shelter is also attempting to raise $1.7 million to renovate an old motel into transitional housing for 24 people — a project that is vital to Madrid-Estrada and senior case manager Rob Vigil as a sign a community can heal and thrive if attention is paid.

“It does take a village,” Madrid-Estrada said. “Everyone is just trying to figure out how to handle it all. We’re the only shelter and transitional housing around.” But Española is likely to need a more intensified effort by government agencies, police, social and health services.

At 7:40 p.m. on a winter night, the homeless gathered at the shelter. They were let in one by one, stripping off coats, emptying pockets, giving names and telling stories. “This is my first time here,” said Sebastian, who drifted up from Santa Fe. “I want to be clean and get a job. ... Is that chili? Can I get a shower?”

He sat next to a shelf that held a bottle of Hershey’s syrup, a can of Barbasol shaving cream and “The Way of the Cross” by Fulton J. Sheen.

Roberta Walker stepped in. She wore pajama pants, two coats and a knit yachting hat with the tag affixed. She was brash and broken. She’d been on the streets more than two years, since her stepfather died. The first of her seven children was born when she was 16. Walker was raised in foster homes. A boyfriend stabbed her. Her drug habit over the decades — her mother was a heroin addict — veered from Tylenol to crack to meth to fentanyl.

She opened a packet of crackers.

“I was a mom,” she said.

Her eyes filled with tears.

“They said I fell through the cracks,” she said, “but no one helped me when I was falling.”

She wiped her nose.

“I want to be alive,” she said. “I’ve seen so many people die. So many in one year. Fentanyl is like modern crack. If you don’t get the measurements just right, you go down like the volume on the radio.”

More people waited outside, wrapped in blankets, sitting against the wall, smoking, shivering, watching others come and go. One went to try his luck at the casino. A couple huddled near a battered car. A few headed toward the glow of tents in the cold stillness of the marshes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.