Naloxone helps prevent opioid deaths. Here’s how to find and use it

- Share via

Over the past 20 years, opioid-related deaths rose 850% in the United States, reflecting the surge in addictions to narcotic painkillers and the influx of fentanyl and other potent synthetic opioids.

To lower the death toll over the long run, we’ll need to reverse the growth in opioid addictions across the country — no easy task, given the drugs’ powerful grip. In the meantime, officials and community groups in Los Angeles County have tried to prevent deaths with proven harm-reduction strategies, most notably putting the drug naloxone in the hands of drug users and the people close to them.

Naloxone is an “opioid antagonist,” according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which means it blocks chemicals in the opioid family (such as heroin, oxycodone, morphine and fentanyl) from attaching to receptors in the nervous system. If administered soon after someone goes into an opioid-related medical emergency, it is remarkably effective at reversing the drug’s effects. And it’s safe too. As the institute put it, “naloxone has no effect on someone who does not have opioids in their system.”

The key, though, is making sure that people have it when they or someone around them needs it. That’s what state and county officials have been trying to do through broad, grass-roots distribution efforts, although the cost of the drug has limited their reach. The branded inhalable version, Narcan, sells for $67.50 per dose. The generic version is about $50.

If you are in close contact with someone who uses opioids or who may encounter it unwittingly — black market pills tainted with lethal amounts of fentanyl have caused a growing number of deaths — you may want to obtain some naloxone and learn how to administer it. Here’s where to find kits in L.A. County, as well as information on how to use them.

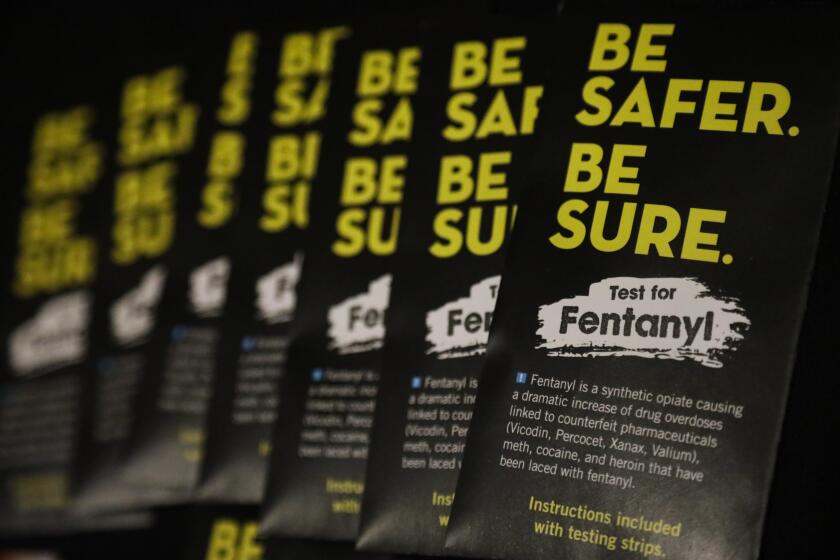

Fentanyl is often mixed with other drugs (including heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine) to increase potency, but it can be deadly. Test kits can help.

Where naloxone kits are available

Healthcare facilities and first responders across the county have naloxone on hand to treat people in an opioid-related health crisis. Hospitals have also begun giving naloxone kits to these patients when they’re discharged, instead of sending them off with just a prescription, said Shannon Knox, director of training and education for Community Health Project L.A.

But that’s a reactive approach. To obtain naloxone proactively, you have several options in L.A. County.

Under a standing order from the state public health officer, community organizations and other entities with permission from the state Department of Public Health can provide the drug “to those at risk of overdose and those in a position to intervene during an opioid-related overdose.” This includes homeless service providers, syringe exchange and other harm reduction programs, drug treatment programs, public health departments and pharmacies.

L.A. County and other jurisdictions that have been actively promoting harm reduction efforts have more sources of free naloxone than those that have shied away from needle exchange programs, such as Orange County. But even in counties with strong naloxone programs, some communities have better access to the kits than others.

The county’s Overdose Education + Naloxone Distribution website lists 27 sites where Community Health Project L.A. and other harm-reduction groups are making naloxone kits available for free. The sites are open only at certain days and times, however, and most operate only one or two days a week. The one site open all day, every day is the Refresh Spot operated by Homeless Health Care Los Angeles at 557 Crocker St. in downtown L.A., where showers, restrooms, wound kits and other supplies and services are also available.

To find a site near you that offers free naloxone, go to laodprevention.org/naloxone.

CVS and Walgreens offer naloxone without a prescription too; you should call ahead to see if the store near you has the medicine in stock. It’s not free, but the cost is offset by at least some of the health insurers serving Southern California.

Knox said that the demand for naloxone greatly exceeds the supply. But the state may soon be able to tap a new source of low-cost injectable naloxone, potentially multiplying the amount that will be available for community distribution.

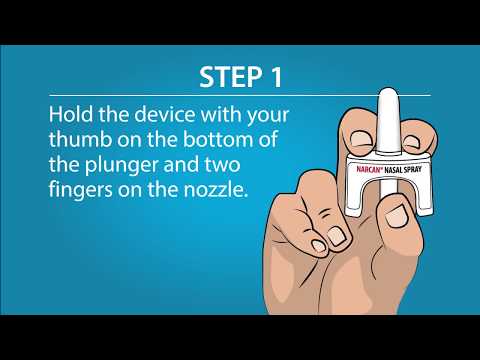

To prevent overdose deaths, Los Angeles County health officials made a push to distribute 50,000 boxes of Narcan — a nasal spray that can block the effects of an opioid overdose — by this summer.

How to use a naloxone kit

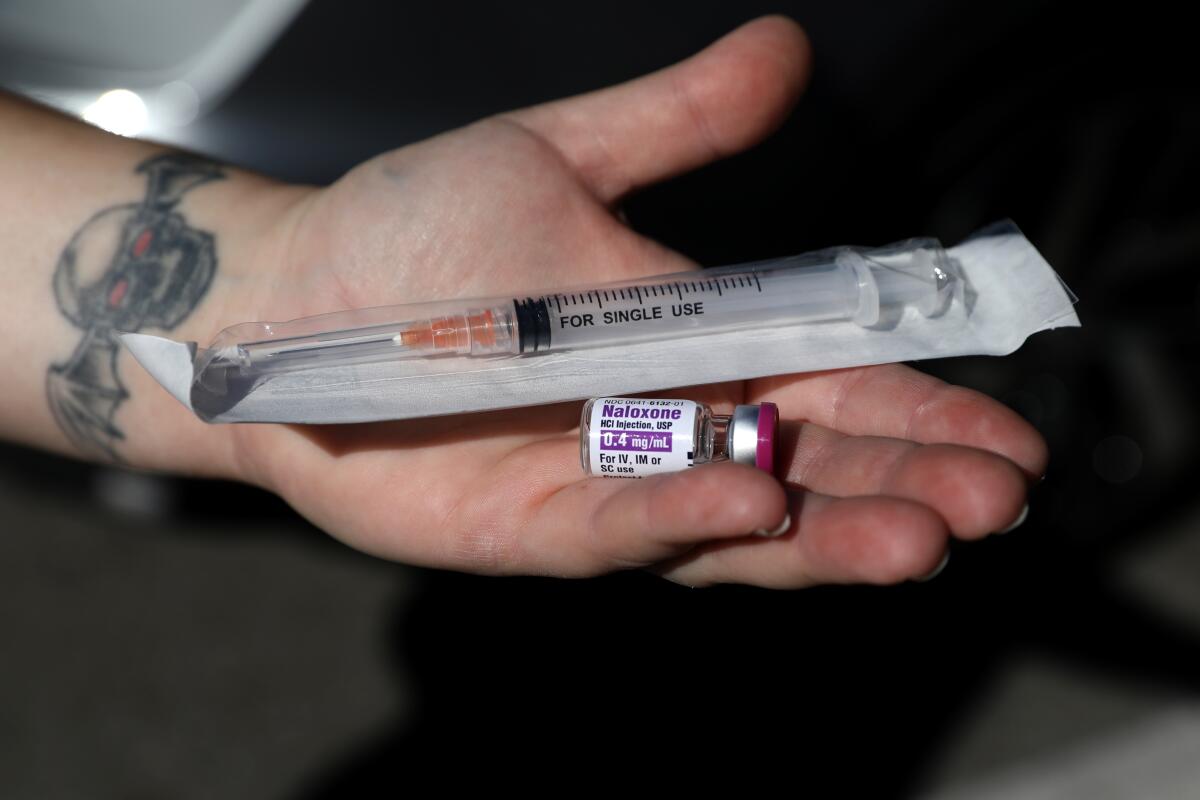

Naloxone comes in two main forms: a spray that’s inhaled through the nose, and a liquid that’s injected into muscles in the arm or leg. The injectable version is significantly less expensive — about $3 per dose, compared with $49 for the generic version of inhalable naloxone — so it’s easier for state and county programs to obtain in large quantities.

Before you open the kit, though, you need to know when to use it. Opioids are painkillers that, at higher doses, can slow a person’s breathing and heart rate, according to the Mayo Clinic. At too great a dose, the person will stop breathing.

The telltale signs that a person is in trouble, health officials say, include passing out and not rousing, breathing slowly or not at all, making gurgling noises, having pupils reduced to pinpoints, and turning gray or blue in the lips or skin. The National Harm Reduction Coalition says that if you can’t wake the person up, try verbal and physical stimulation — calling the person’s name, rubbing your knuckles into the middle of the chest or on the upper lip, and pinching the back of his or her arm.

Once you’ve determined that the person is in crisis, experts say, call 911 and report that you have someone who appears to have overdosed (and, if applicable, that the person isn’t breathing). Then it’s time to give the person naloxone.

When you pick up a kit, you’ll also be given instructions in how to use it. Knox said it takes just a few minutes to get up to speed on how to administer the drug in either its inhalable or injectable forms. There are several formats available, including auto-injectors with pre-loaded syringes and sprays that may need to be pumped into each nostril. Make sure to familiarize yourself with the specific version you obtain; the American Medical Assn. offers this helpful rundown of each of the major formats.

If you have naloxone in a vial, you’ll need to put 1 cc of the medicine into the syringe included in the kit. It’s important to make sure when loading the syringe that you’re drawing in liquid from the vial, not air. Then you insert the needle into the person’s upper arm or the front of the thigh and press the plunger all the way down.

If the person you’re trying to help remains unresponsive for two to three minutes, administer a second dose of naloxone. In the meantime, the harm reduction coalition says, you should check to make sure the person is breathing. If not, perform rescue breathing.

For years, this Canadian city has hosted safe consumption sites for addicts. They’ve saved lives, but with some painful tradeoffs.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.