The Amazon’s Yanomami people are being decimated by disease and mining in Brazil. Here’s why

- Share via

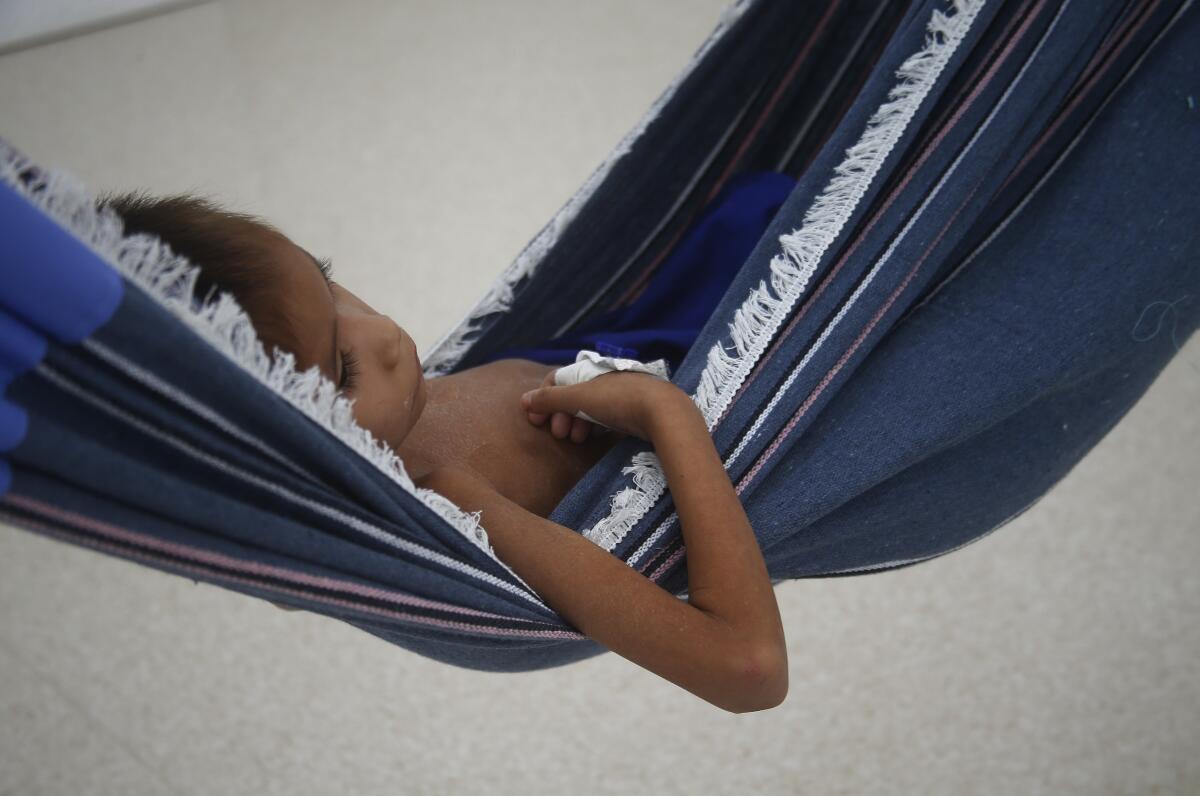

BOA VISTA, Brazil — Severe malnutrition and disease, particularly malaria, are decimating the Yanomami population in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, and this month the federal government declared a public health emergency.

Although many in Brazil were left wondering how the calamity could materialize seemingly overnight, it didn’t come as a surprise to those familiar with the Yanomami’s circumstances, who have issued warnings for years.

Here’s what you need to know about how the Yanomami reached this tragic point:

Who are the Yanomami?

An estimated 30,000 Yanomami people live in Brazil’s largest indigenous territory, which covers an area roughly the size of Portugal and stretches across Roraima and Amazonas states in the northwest corner of Brazil’s Amazon.

Some also live in southern Venezuela. They provide food for themselves by hunting, gathering, fishing, and growing crops in large gardens cleared from the forest.

Every few years, the Yanomami move from one area to another, allowing the soil to regenerate.

What is causing the crisis?

Illegal gold miners arrived in Yanomami territory during the 1980s but were largely expelled. They have flooded back in recent years, attracted by high gold prices and urged on by former President Jair Bolsonaro.

Their numbers surged to 20,000 during Bolsonaro’s administration, according to estimates from environmental and Indigenous rights groups.

Miners destroy the habitat of animals that the Yanomami hunt, and occupy fertile land that the Yanomami use to farm.

The miners also process ore with mercury, which poisons the rivers that the Yanomami depend upon for fish.

Mining creates pools of stagnant water where mosquitoes that transmit illness breed. And miners relocating to exploit new areas spread sickness to native people who possess low immunity due to limited contact with outsiders.

“The impacts accumulate,” said Estevão Senra, a geographer and researcher at Instituto Socioambiental, an environmental and Indigenous rights nonprofit. “If (the Yanomami) are sick, they miss the right moment to open a new area for farming, compromising their future.”

An AP investigative series last year detailed how the scale of prospecting on Indigenous lands exploded in recent years, illegally mined gold seeps into global supply chains, and mining stokes divisions within Indigenous territories.

Was this a sudden disaster?

No. It has spiraled over the course of several years.

Eight of 10 children ages 5 or younger had chronic malnutrition in 2020, according to a study in two Yanomami regions by UNICEF and Brazilian state health research institute Fiocruz.

There were 44,069 cases of malaria in two years, meaning the entire population was infected, some people more than once, Roraima state’s public prosecutor’s office said in 2021, citing data from Brazil’s countrywide disease notification system.

Curable conditions such as flu, pneumonia, anemia and diarrhea become life-threatening. At least 570 Yanomami children died from complications of untreated diseases during Bolsonaro’s term, from 2019 to 2022, according to Health Ministry data obtained by independent local news website Sumauma. That marked a 29% increase from the prior four years.

The documentary “The Last Forest” observes an Amazon tribe, the Yanomami, attempting to preserve its culture from an encroaching world.

There was a greater need for medical care, but services for Indigenous people deteriorated under Bolsonaro, said Adriana Athila, an anthropologist who has studied public healthcare for the Yanomami, which is provided by one of the special districts designed for the needs of Indigenous communities.

There have also been reports of miners taking control of health facilities and airstrips in Yanomami territory for their own use. Local leaders have been sounding the alarm for years.

“The miners are destroying our rivers, our forest and our children. Our air is no longer pure, our game is disappearing, and our people are crying out for clean water,” Júnior Hekurari Yanomami, president of the Yanomami local health council, wrote on Twitter last March. “We want to live, we want our peace back and our territory.”

The recent influx of miners severely exacerbated the disruption of traditional Yanomami life that took place over the prior two decades.

That was caused by the introduction of social welfare programs that forced people to make weeks-long trips to collect their benefits in cities, where they often remain for extended periods in squalid conditions. And the establishment of non-Indigenous institutions, such as military bases, medical posts, and religious missions, transformed some temporary villages into permanent settlements, depleting hunting and soil resources.

What was Bolsonaro’s role?

As a young lawmaker in the 1990s, Bolsonaro fiercely opposed the creation of the Yanomami territory. More recently, he openly championed mining in Indigenous lands and the integration of native peoples into modern society.

Environmentalists, activists and the vast majority of Indigenous groups slammed his efforts and warned of devastating effects.

He pressured Congress for an emergency vote on the bill his mining and justice ministries drafted and presented in 2020 to regulate the mining of Indigenous lands, but lawmakers demurred. Even large mining companies repudiated the proposal.

Wildcat gold miners, for their part, were undeterred, “because they knew the government would turn a blind eye,” Senra said.

Hekurari accused Bolsonaro’s administration of ignoring some 50 letters pleading for help. That is in part why some, including President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, have accused Bolsonaro of genocide.

Bolsonaro has called such claims “another left-wing farce.” He said that during his administration the health ministry provided more than 53 million basic-care services to Indigenous people.

How has Lula responded?

Brazil’s incoming president has promised to eliminate all deforestation by 2030, which would be a complete change of course for Brazil compared to the last four years.

After defeating Bolsonaro in the October election, Lula took power Jan. 1. The change created an expectation that the burgeoning crisis would finally receive attention, said Senra, given the sharp reversal for Amazon policy Lula had outlined on the campaign trail. Indeed, Lula dispatched a team to Yanomami territory last week and on Saturday traveled to Boa Vista, the nearby capital of Roraima, where many Yanomami people have been flown for treatment.

Following Lula’s Jan. 20 declaration of a medical emergency, the army began flying food kits into Yanomami territory and set up a field hospital in Boa Vista, while the health ministry put out a nationwide call for medical professionals to volunteer.

Marcos Pelligrini, a former doctor within Yanomami territory and professor of collective health at the Federal University of Roraima in Boa Vista, said that he felt relief upon seeing army helicopters transporting food kits.

“It’s a moment of hope,” he said.

But the miners still must be removed from the region by the Federal Police and environment regulator Ibama, with help from the defense ministry, Minister for Indigenous Peoples Sonia Guajajara told newspaper Estado de S. Paulo.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.