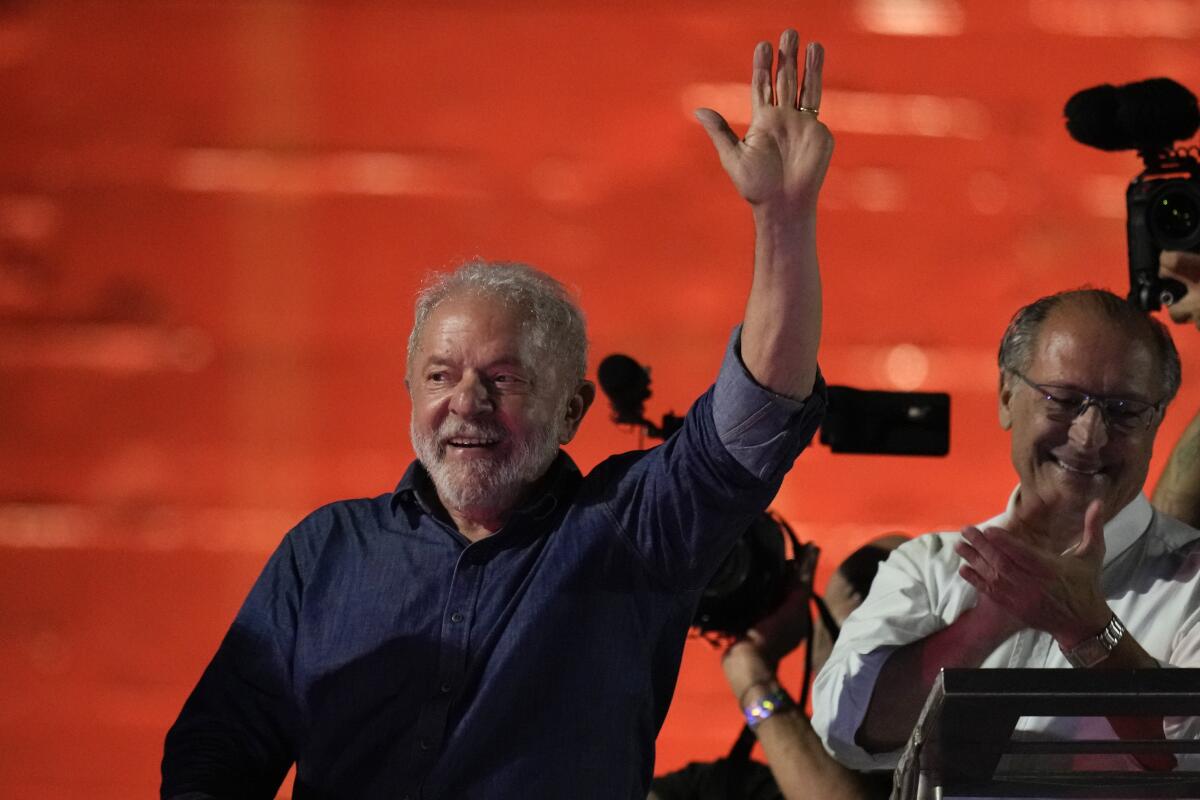

Lula defeats Bolsonaro to become Brazil’s president — again

- Share via

RIO DE JANEIRO — Brazilians delivered a very tight victory to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a bitter presidential election, giving the leftist former president another shot at power in a rejection of incumbent Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right politics.

Da Silva, who is known as Lula, received 50.9% of the vote and Bolsonaro 49.1%, according to Brail’s election authority. Yet hours after the results were in — and congratulations poured in from world leaders — Bolsonaro had yet to publicly concede or react in any way, as truckers blockaded some roads across the country in protest.

Bolsonaro’s campaign had made repeated, and unproven, claims of possible electoral manipulation before the vote, raising fears that, if he lost, he would not accept defeat and try to challenge the results.

For Da Silva, 77, the high-stakes election was a stunning comeback. His imprisonment for corruption sidelined him from the 2018 election won by Bolsonaro, who has used the presidency to promote conservative social values while also delivering incendiary speeches and testing democratic institutions.

“Today the only winner is the Brazilian people,” Da Silva said in a speech at a hotel in downtown Sao Paulo. “This isn’t a victory of mine or the Workers’ Party, nor the parties that supported me in [my] campaign. It’s the victory of a democratic movement that formed above political parties, personal interests and ideologies so that democracy came out victorious.”

Da Silva is promising to restore the country’s more prosperous past and to govern beyond his leftist Workers’ Party. He wants to bring in centrists and even some leaning to the right who voted for him for the first time. Yet he faces headwinds in a politically polarized society where economic growth is slowing and inflation is soaring.

His victory marks the first time since Brazil’s 1985 return to democracy that the sitting president has failed to win reelection. The election in Latin America’s biggest economy extended a wave of recent leftist victories in the region, including in Chile, Colombia and Argentina.

As Da Silva spoke to his supporters — promising to “govern a country in a very difficult situation” — Bolsonaro had yet to concede.

It was the country’s closest election in more than three decades. Just over 2 million votes separated the two candidates with 99.5% of the vote counted. The previous closest race, in 2014, was decided by a margin of 3.46 million.

Da Silva’s inauguration is scheduled to take place Jan. 1. He last served as president from 2003-10.

Thomas Traumann, an independent political analyst, compared the results to President Biden’s 2020 victory, saying Da Silva is inheriting a divided nation.

“The huge challenge that Lula has will be to pacify the country,” he said. “People are not only polarized on political matters but also have different values, identity and opinions. What’s more, they don’t care what the other side’s values, identities and opinions are.”

Congratulations for Da Silva — and for Brazil — began to pour in from around the world Sunday evening, including from Biden, who highlighted the country’s “free, fair, and credible elections.” The European Union congratulated Da Silva in a statement, commending the electoral authority for its effectiveness and transparency throughout the campaign.

Bolsonaro had been leading throughout the first half of the count. When Da Silva overtook him, motorists in downtown Sao Paulo began honking horns. People in the streets of Rio de Janeiro’s Ipanema neighborhood could be heard shouting, “It turned!”

Da Silva’s headquarters in a downtown Sao Paulo hotel erupted once the final result was announced.

“Four years waiting for this,” said Gabriela Souto, one of the few supporters allowed in due to heavy security.

Outside Bolsonaro’s home in Rio de Janeiro, ground zero for his support base, a woman atop a truck delivered a prayer over a speaker, then sang excitedly, trying to generate energy. But supporters decked out in the green and yellow of the flag barely responded. Many perked up when the national anthem played, singing along loudly with hands over hearts.

Polls closed at 5 p.m. nationwide. Because the vote was conducted electronically, the results came quickly.

President Biden warns that global hunger could rise after Russia halts a U.N.-brokered deal to allow safe passage for ships carrying Ukrainian grain.

Voting stations in the capital, Brasilia, were crowded by early in the day. At one, retired government worker Luiz Carlos Gomes said he would vote for Da Silva.

“He’s the best for the poor, especially in the countryside,” said Gomes, 65, who hails from Maranhao state in the poor northeast region. “We were always starving before him.”

Most opinion polls had given a lead to Da Silva, though analysts agreed that the race grew increasingly tight in recent weeks.

For months, it appeared that Da Silva was headed for easy victory as he kindled nostalgia for his 2003-10 presidency, when Brazil’s economy was booming and welfare helped tens of millions join the middle class.

But while Da Silva topped the Oct. 2 first-round elections with 48% of the vote, Bolsonaro was a strong second at 43%, showing that opinion polls had significantly underestimated the incumbent’s popularity. Many Brazilians support Bolsonaro’s defense of conservative social values, and he shored up support with vast government spending.

More than 150 million Brazilians were eligible to vote, yet about 20% abstained in the first round. Both Da Silva and Bolsonaro focused efforts on driving turnout. Almost 400 cities made public transportation free on election day, according to the nonprofit Free Fares for Democracy, and the electoral authority prohibited federal highway police from affecting voters’ passage on public transit.

Still, there were multiple reports of checkpoints. The newspaper Folha de S.Paulo reported that highway police stopped more than 500 buses as of 12:35 p.m. local time — a 70% increase from the first-round vote — citing documents and internal data.

The head of the election authority ordered police to cease the actions. The Workers’ Party filed a request for the police director’s arrest.

Human Rights Watch, an international nonprofit, said it was “very concerned” about the reports of roadway operations and confusion on public transit.

Earlier, the subway in the capital of Minas Gerais — a crucial battleground state — was charging fares in defiance of a regional court ruling. The head of the election authority ordered the federal company that runs the subway to eliminate fares immediately or be charged with electoral crimes. Afterward, local television broadcast images of passengers passing through turnstiles unimpeded.

Bolsonaro, sporting green and yellow, was first in line to cast his vote at a military complex in Rio de Janeiro.

“I’m expecting our victory, for the good of Brazil,” he told reporters afterward. “God willing, we will be victorious this afternoon. Actually, Brazil will be victorious.”

Da Silva voted Sunday morning in Sao Bernardo do Campo, a city outside Sao Paulo where he lived for decades and started his political career as a union leader. He wore white, as he often has during the campaign, rather than his party’s traditional red.

“Today we are choosing the kind of Brazil we want, how we want our society to organize. People will decide what kind of life they want,” Da Silva told reporters. “That’s why this is the most important day of my life. I am convinced that Brazilians will vote for a plan under which democracy wins.”

The candidates presented few proposals for the country’s future beyond affirming that they would continue a welfare program for poor people, despite limited funding. They railed against one another and launched online smear campaigns — with considerably more attacks coming from Bolsonaro’s camp.

On the eve of the election, Bolsonaro shared video on Twitter of his endorsement by former U.S. President Trump, who said Bolsonaro has secured for Brazil respect on the world stage. Da Silva has criticized Bolsonaro for the nation’s fallen stature abroad, highlighting the dearth of state visits and bilateral meetings.

“Don’t lose him, don’t let that happen,” Trump said in the video. “It would not be good for your country. I love your country, but it would not be good. So get out and vote for President Bolsonaro. He’s doing the job like few people could.”

Bolsonaro’s four years in office have been marked by conservatism and defense of traditional Christian values. He claimed that his rival’s return to power would usher in communism, legalized drugs, abortion and the persecution of churches — none of which occurred during Da Silva’s earlier eight years in office.

On Sunday, Livia Correia and her husband, Pedro, brought their two young kids to a voting station in Rio’s Copacabana neighborhood, where Bolsonaro supporters regularly rally. They all wore green-and-yellow shirts. Livia, 36, said she voted for Bolsonaro because he defends the things she holds dear: “Family values, God and freedom of expression.”

Da Silva homed in on Bolsonaro’s widely criticized handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and said the president failed to care for society’s neediest. He also painted Bolsonaro as an opponent of the Amazon rainforest, given that he defanged environmental authorities and presided over a surge in deforestation.

But for many, the record of Da Silva’s Workers’ Party was equally off-putting. A sprawling investigation revealed the party’s involvement in vast corruption scandals that ensnared top politicians and executives.

Da Silva himself was imprisoned for 19 months for corruption and money laundering. The Supreme Court annulled his convictions in 2019, on the grounds that the judge was biased and colluded with prosecutors. That did not stop Bolsonaro from reminding voters of the convictions.

The president’s digital mobilization was on display in recent days as his campaign introduced fresh — and unproved — claims of possible electoral manipulation. That revived fears that Bolsonaro could challenge the election results — much like Trump, whom he admires, has done.

For months, Bolsonaro has claimed that the nation’s electronic voting machines are prone to fraud, though he never presented evidence, even after the electoral authority set a deadline for him to do so.

More recently, allegations focused on airtime for political ads. Bolsonaro’s campaign claimed that radio stations may have hurt the candidate by failing to air more than 150,000 electoral spots.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.