Ferdinand Marcos Jr. wins Philippine presidential election, unofficial count shows

- Share via

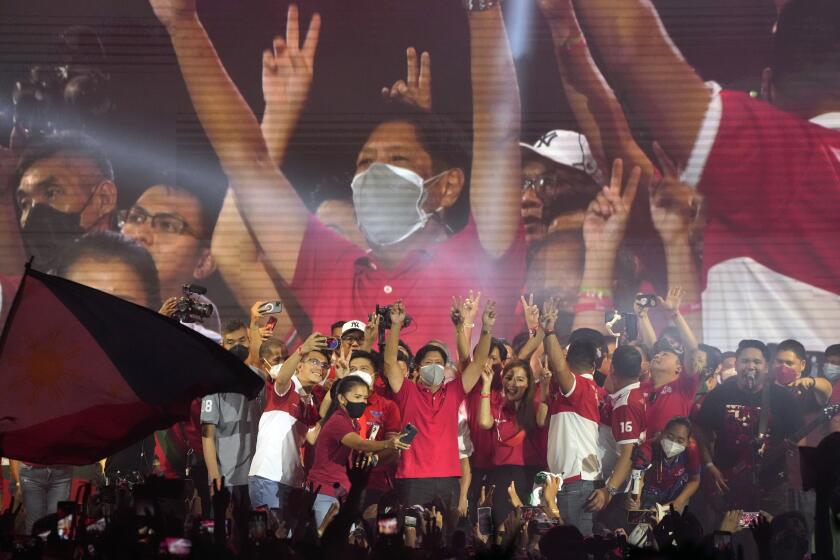

MANILA — Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the son of the former Philippine dictator, appears to have been elected president by a landslide in an astonishing reversal of the 1986 “People Power” pro-democracy revolt that ousted his father.

Marcos, 64, had more than 30.8 million votes in the unofficial results, with more than 97% of the votes tabulated as of Tuesday afternoon. His nearest challenger, Vice President Leni Robredo, a champion of human rights, had 14.7 million votes in Monday’s election, and boxing great Manny Pacquiao appeared to have the third-highest total with 3.5 million.

Marcos’ running mate, Sara Duterte, mayor of southern Davao city and daughter of outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte, held a formidable lead in the separate vice presidential race.

The alliance of the scions of two authoritarian leaders combined the voting power of their families’ political strongholds in the north and south but compounded worries of human rights activists.

Dozens of anti-Marcos protesters rallied at the Commission on Elections, blaming the agency for the breakdown of vote-counting machines and other issues that prevented people from casting their votes. Election officials said the impact of the malfunctioning machines was minimal.

A group of activists who suffered under the dictatorship said it was enraged by Marcos’ apparent victory and would oppose it.

Ferdinand Marcos ruled the Philippines with an iron fist. Now a TikTok disinformation campaign is propelling his son toward the presidency.

“A possible win based on a campaign built on blatant lies, historical distortions and mass deception is tantamount to cheating your way to victory,” said the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses and Martial Law. “This is not acceptable.”

Etta Rosales, a former Commission on Human Rights chairwoman, who was twice arrested and tortured under martial law in the 1970s, said the younger Marcos’ apparent victory drove her to tears but would not stop her from continuing efforts to hold his family to account.

“I’m just one among the many who were tortured. Others were killed; I was raped. We suffered under the Marcos regime in the fight for justice and freedom, and this happens,” Rosales said.

During their campaign, Marcos and Duterte avoided volatile issues and steadfastly stuck instead to a battle cry of national unity, even though their fathers’ presidencies opened some of the most turbulent divisions in the country’s history.

After decades out of power in the Philippines, the Marcos family is on the verge of winning the presidency. We examine how social media played a crucial role in whitewashing their past.

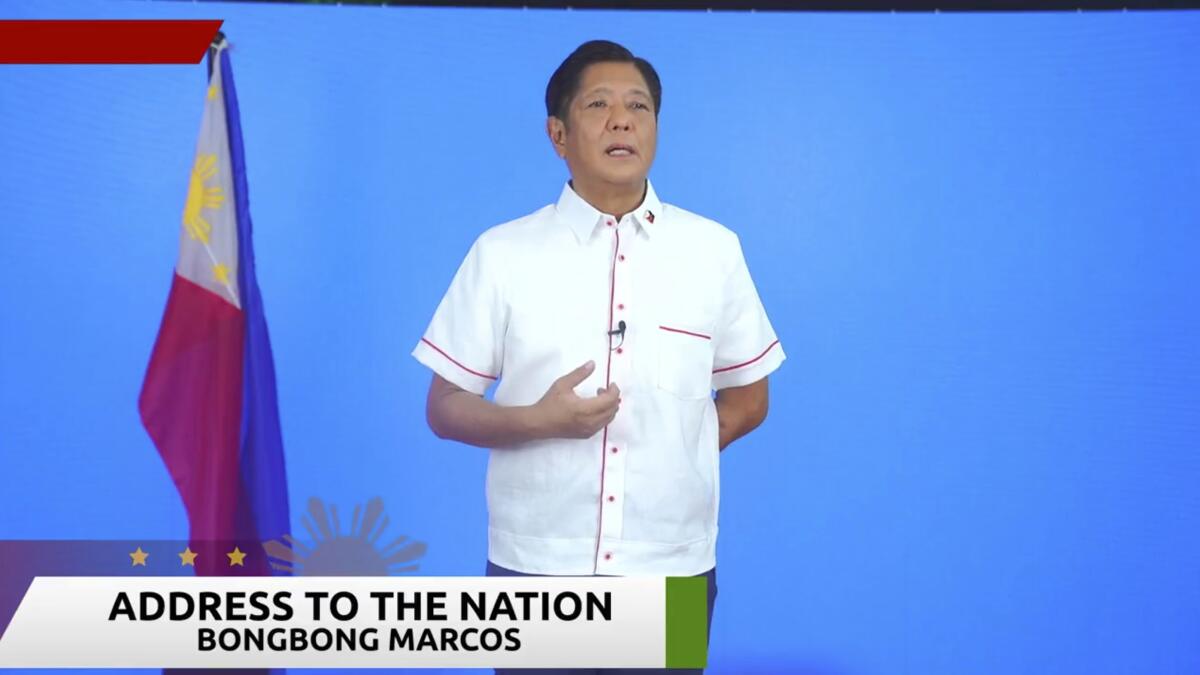

Marcos has not claimed victory but thanked his supporters in a late-night “address to the nation” video, in which he urged them to stay vigilant until the vote count was completed.

“If we’ll be fortunate, I’ll expect that your help will not wane, your trust will not wane, because we have a lot of things to do in the times ahead,” he said.

Robredo has not conceded defeat but acknowledged Marcos’ massive lead in the unofficial count. She told her supporters that the fight for reforms and democracy wouldn’t end with the election.

“The voice of the people is getting clearer and clearer,” she said. “In the name of the Philippines, which I know you also love so dearly, we should hear this voice because, in the end, we only have this one nation to share.”

The remains of thousands killed in the Philippines’ war on drugs could be tossed in pits as families struggle to pay for burial sites amid a pandemic.

She asked her supporters to continue to stand up: “Press for the truth. It took long for the structure of lies to be erected. We have the time and opportunity now to fight and dismantle this.”

The election winner will take office June 30 for a single six-year term as leader of a nation that has been hit hard by COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns and long-running problems of crushing poverty, gaping inequalities, Muslim and communist insurgencies, and deep political divisions.

The next president will also likely face demands to prosecute outgoing President Duterte for thousands of killings during his anti-drug crackdown — deaths already under investigation by the International Criminal Court.

Amnesty International said it was deeply concerned by Marcos and Sara Duterte’s avoidance of discussing human rights violations, past and present, in the Philippines. “If confirmed, the Marcos Jr. administration will face a wide array of urgent human rights challenges,” the rights group said in a statement Tuesday.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Human Rights Watch also called for Marcos, if he takes office, to improve the human rights situation in the Philippines.

“He should declare an end to the ‘war on drugs’ that has resulted in the extrajudicial killing of thousands of Filipinos, and order the impartial investigation and appropriate prosecution of officials responsible for these unlawful killings,” said Phil Robertson, the group’s deputy director for Asia.

Marcos, a former provincial governor, congressman and senator, has defended the legacy of his father and steadfastly refused to acknowledge or apologize for the massive human rights violations and plunder under his father’s strongman rule.

After his ouster by the largely peaceful 1986 uprising, the elder Marcos died in 1989 while in exile in Hawaii without admitting any wrongdoing, including accusations that he, his family and cronies amassed an estimated $5 billion to $10 billion while he was in power. A Hawaii court later found him liable for human rights violations and awarded $2 billion from his estate to compensate more than 9,000 Filipinos who filed a lawsuit against him for torture, incarceration, extrajudicial killings and disappearances.

His widow, Imelda Marcos, and their children were allowed to return to the Philippines in 1991 and worked on a stunning political comeback, helped by a well-funded social media campaign to rehabilitate the family name.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.