- Share via

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the son of the late president, has garnered a massive following through TikTok, as misleading videos attempt to rebrand his family’s legacy.

- Share via

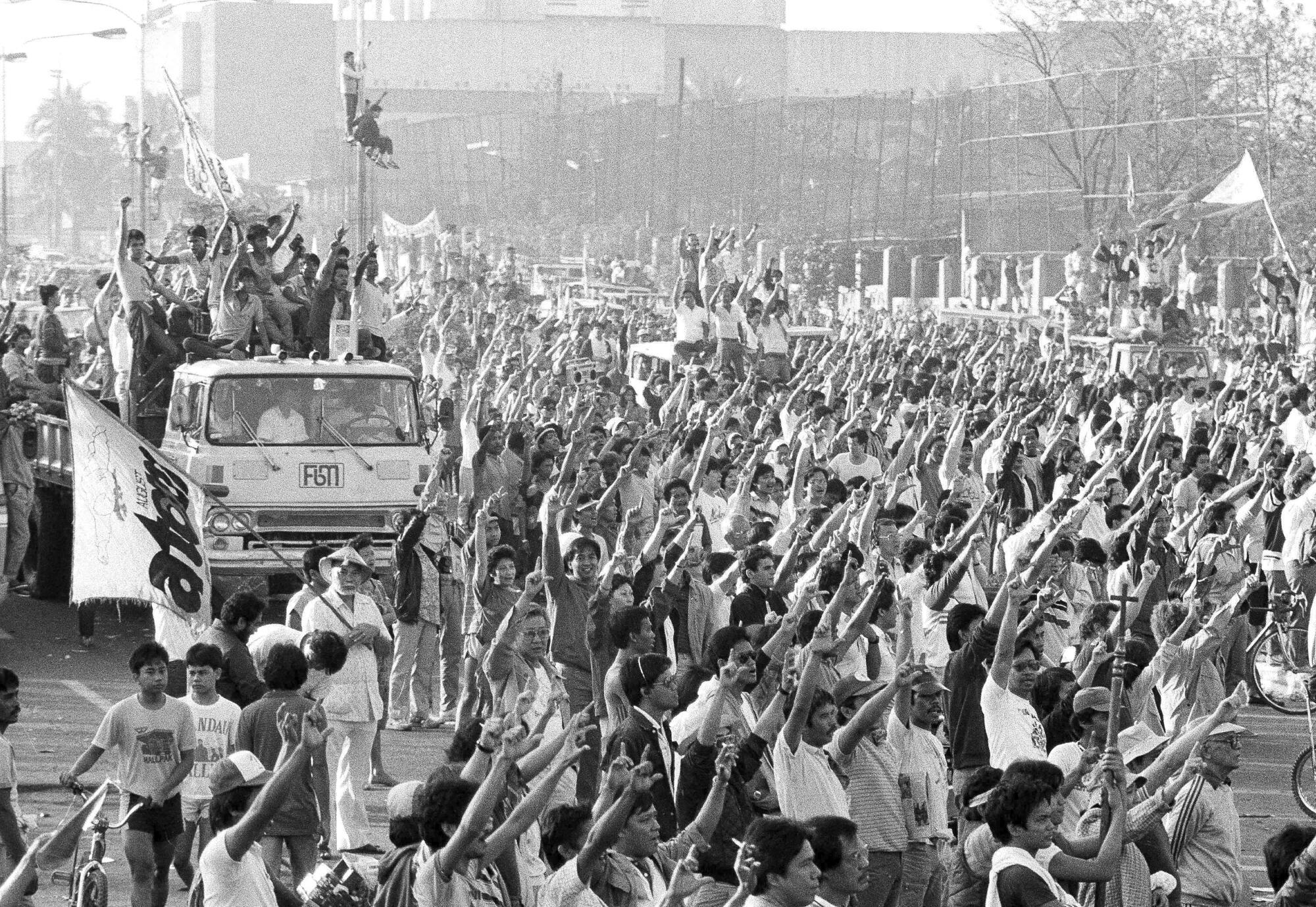

MANILA — During the 14 years that Ferdinand Marcos Sr. ruled the Philippines under martial law, he ordered the killings of thousands of political opponents and plundered billions of dollars from the national coffers so his family could live in extreme luxury.

But Crisdel Almarez, who was born a decade after the dictator was overthrown, knows that period only as a time of national bliss.

She knows this from TikTok.

“TikTok remembers the good times,” said Almarez, 25, who sells home appliances at a mall here in the capital. “We don’t believe the history books anymore. We have social media now.”

Her alternative reality was engineered by Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. — the dictator’s 64-year-old son and the front-runner in the presidential election to be held Monday. Aided by a network of online trolls, his campaign has harnessed TikTok to rewrite his father’s violent history for a generation too young to have lived under the period’s defining martial law.

The Chinese-owned app best known for its trendsetting dance memes is brimming with slick videos portraying the Marcos family as a political dynasty that brought Kennedy-esque glamour and global respect to the presidential palace. The snippets establish a narrative, but more importantly for millions of young Filipinos, they deliver a vibe.

There’s a retro clip of the resplendently dressed first lady, Imelda Marcos, meeting with Britain’s Prince Charles set against Swedish pop singer Tove Lo’s soaring hit “Habits.”

Another video, which has more than 1 million views, compares the gaits of several former presidents, raising the volume of Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” as Marcos Sr. strides along confidently in a flawlessly pressed barong.

“FEM Walk Hits DIFFERENT,” reads the caption using the acronym for the dictator’s full name, Ferdinand Emmanuel Marcos.

Marcos Jr. is portrayed as a loving family man, a facsimile of his decisive father, and someone set to restore pride to a country ravaged by COVID-19 and economic hardship.

One TikTok account is dedicated to vintage footage of the family, including a video set to the viral Doja Cat and Gwen Stefani mash-up “You Right X Luxurious” that features a beaming young Marcos Jr. with a 1970s perm.

“They’re trying to win over a chunk of the Filipino population who never went through the economic difficulties and the human rights violations of the martial law years,” said Ronald Mendoza, dean of the Ateneo School of Government in Manila. “They’re being misled by a false nostalgia.”

Experts said the disinformation campaign has all the hallmarks of a shadowy industry of advertising and public relations firms whose clients include corporations, celebrities and political campaigns.

Trolls appear to be operating swarms of anonymous accounts that cross-post pro-Marcos content from Facebook and YouTube to TikTok. When one account uploads a new video, thousands of others immediately deliver views or shares that trip the app’s algorithm to send it to more user feeds.

“There’s a machinery that takes over,” said Armand Dean Nocum, a semi-retired public relations executive who has run troll farms for more than a decade, mostly on Facebook and YouTube. “They can get millions of views.”

A Manila-based political strategist working on a mayoral campaign said he pays TikTok influencers between $95 and $570 for each clip they post of themselves wearing campaign paraphernalia, singing a campaign jingle or instructing viewers to vote for his candidate.

As public anger mounted last year over delayed plans to shake up the Philippines’ outage-plagued telecommunications sector, angry comments and one-star ratings flooded a government-run Facebook page.

“We identify which TikTokers have the most followers in certain areas and enlist them to make videos,” said the strategist, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

He said it was well known in the industry that the Marcos Jr. campaign employs the same strategy, but on a much bigger scale.

“Marcos trolls and support pages are instructed by social media managers to drive traffic and eyeballs to them,” he said.

The Marcos Jr. campaign did not respond to a request for an interview, but the candidate has denied spreading misinformation or using trolls, telling CNN Philippines last month: “Find me one. Show me one. Just one. They don’t exist.”

Online deception is of course nothing new in politics — witness the U.S. election of 2016. That same year in the Philippines, the current president, Rodrigo Duterte, rode into power with the aid of troll armies on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter.

TikTok — one of the world’s fastest growing apps, with a billion users and ad revenues forecast to double this year to $11.6 billion — has one crucial distinction from those competitors: It reaches an almost exclusively young audience.

In a country where more than half of registered voters are 40 or younger, TikTok has been particularly effective in efforts to whitewash the history of the Marcos family. That era already gets glossed over in the country’s public schools, with one recent study of fifth- and sixth-grade history textbooks determining that as few as 6% of pages were dedicated to teaching the martial law era.

Marcos Jr. narrowly lost the race for vice president in 2016 (presidents and vice presidents are elected separately in the Philippines). This time, he is seeking the presidency with Duterte’s daughter, Sara Duterte-Carpio, as his running mate.

He is leading his closest rival, Leni Robredo, the current vice president, by 33 percentage points in recent polls — in large part because of overwhelming support from millennial and Generation Z voters.

Korraine Nichole Anne Mangaoang, a 22-year-old college student, said she knew little about Marcos Sr. until she downloaded TikTok at the outset of the pandemic to pass time.

At first, the app’s algorithm catered to her interests, delivering cooking and foraging videos. It wasn’t long, though, before pro-Marcos content started showing up. It left an impression.

“The Marcos family legacy was a golden age of peace and prosperity,” said Mangaoang, who lives in the city of Aringay, 130 miles north of Manila. “Life was easier under Marcos. We had order, and corruption was minimal.”

Mangaoang, who described TikTok as “addicting,” said she plans to vote for Marcos Jr. and dismissed negative portrayals of the clan as lies.

“The accusations against the family have never been proven in court,” Mangaoang said, repeating a falsehood common on social media.

The emergence of TikTok as a font of misinformation is bringing more scrutiny to a company that has been awash with pro-Kremlin propaganda since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine more than two months ago.

TikTok, which is owned by the Beijing-based developer ByteDance, declined several requests for an interview and instead shared a statement: “Our Community Guidelines prohibit harmful misinformation, including content which is inauthentic, or designed to mislead our community about elections.”

It went on to say that it works with the news agency Agence France-Presse “to help us assess the accuracy of content, and remove misinformation as we identify it.”

The private wire service has debunked several pro-Marcos social media posts — pointing out, for example, that a photograph of the mascot of popular fast-food chain Jollibee had been doctored — but TikTok has not been a particular focus.

The Philippines introduces an all-female coast guard radio unit as it challenges Chinese aggression in the South China Sea after years of inaction.

Because TikTok consists entirely of videos, there is no simple way to efficiently sift through it for lies. Facebook and YouTube are far easier to review using software because they include text. The TikTok algorithm also helps trolls because it includes an element of randomness — unlike other platforms that primarily serve up what their algorithms determine users want.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer published an investigation last month declaring the app a political battleground where lies from the Marcos Jr. camp go unchecked.

Those findings mirrored a study released late last year by Vera Files, a fact-checking operation in Manila, showing that disinformation across all platforms overwhelmingly benefited Marcos Jr. and targeted his chief rival, Robredo.

Vera Files debunked claims that the Philippine economy was second only to Japan’s during Marcos Sr.’s reign and that the highest bar exam score in the nation’s history belonged to the dictator.

Other lies are equally inane, such as the claim that Marcos Jr.’s supporters formed the longest motorcade on record.

Guinness World Records put out a statement correcting that. It also dispelled the claim that its recent decision to take down Marcos Sr.’s record for the “greatest robbery of a government” was anything other than part of its normal review process.

Other disinformation has been more malicious, including sex videos falsely claiming to involve two of Robredo’s daughters.

An army of trolls amplifies online support for Marcos Jr.

“I went from having 4,000 followers to over 40,000,” said Glen Cuyos, a 38-year-old choreographer, explaining what happened last fall after he posted a video of a campaign appearance in his hometown of Tagum. “I was so surprised and happy.”

Brittany Kaiser, a former employee of the political consultancy Cambridge Analytica, told journalist Maria Ressa in 2020 that Marcos Jr. had once sought help from the now-defunct firm, best known for its work on President Trump’s 2016 campaign and the revelation that it harvested personal data from 50 million Facebook accounts in the United States.

Although the campaign cranks out misinformation about his father’s dictatorship, Marcos Jr. barely talks about it. Whenever journalists ask him about corruption or executions during that time, he has two stock replies: “Fake news” and “Let the courts decide.”

Computer scientists say the campaign highlights how it is becoming harder to expose disinformation as technology grows more sophisticated.

There is no shortage of unwitting targets — including Almarez.

Tired of earning less than minimum wage in one menial job after another, she has come to scorn college graduates who are “full of pride” and “go against the government” and to view Robredo, a human rights lawyer before she became vice president, as a “puppet of the elite.”

She sees the Philippines as a country with “no jobs” and “no security.”

As long as she can keep her phone topped off with prepaid data capacity, she has found an escape each night on her long bus commute across the capital.

Still wearing her uniform — an itchy white shirt and an orange vest — she retreats to TikTok and imagines how much better life could be under another Marcos.

Special correspondent Lorela Sandoval in San Fernando City, Philippines, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.