They’re key allies of Benjamin Netanyahu. They’re also fueling Israel’s big COVID-19 spike

- Share via

JERUSALEM — Two weeks ago, as the Israeli government grappled with whether to lift its second national coronavirus lockdown, families frazzled over the shutdown of schools were treated to the jarring sight of ultra-Orthodox children boisterously returning to class.

Some of the kids wore masks, and some appeared to be directed toward learning pods. But mostly, scrums of boys rushed into their reopened talmudei torah, as the Bible-centered elementary schools for ultra-Orthodox boys are called.

These children — or, more precisely, their parents — were following the edict of Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky, the most prominent ultra-Orthodox voice in Israel, who ordered the talmudei torah to open on the same day that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government decided to keep schools shut.

Kanievsky’s defiance of the lockdown provoked widespread outrage. But it drew almost no pushback by Israeli authorities, who have cracked down only halfheartedly at best on the rule-breaking and virus-spreading activities in the ultra-Orthodox community, such as communal study and crowded weddings, that are fueling a massive second wave of coronavirus cases here.

What to do about the haredim, as the ultra-Orthodox are called in Israel, has now become the greatest test of Netanyahu’s response to the pandemic. Ultra-Orthodox Israelis account for about 11% of the population but more than 50% of the COVID-19 patients ages 65 and older who are filling hospitals, according to the Israeli Health Ministry.

But the kid-glove treatment that the haredim have received has highlighted the outsize influence their leaders wield in Israel — and the extent of Netanyahu’s dependence on them to stay in power. Far from the image he likes to project of a strong leader, Israel’s longest-serving premier remains in political hock to a small religious minority and their demands, even in the midst of a raging public health crisis.

In Israel, the holiest period on the Jewish calendar has coincided with the world’s first reimposed national coronavirus lockdown.

Netanyahu is also the first Israeli prime minister to be indicted on criminal charges, and he is on trial on three corruption counts that could result in a 10-year prison sentence. That legal vulnerability, and his rickety coalition agreement with centrist former rival Benny Gantz, has only increased his reliance on ultra-Orthodox parties. Keeping their support, even at a very high cost, is a “strategic imperative” that has guided Netanyahu’s entire career, said Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute, an independent Jerusalem think tank.

“As long as he accepted 100% of their demands in the domestic arena,” Plesner said, “Netanyahu understood that ensuring they’re on his side will pretty much guarantee him something like a monopoly over political power.”

If until now the majority of Israelis went about their business oblivious to the intricacies of Netanyahu’s political maneuvering, the coronavirus crisis has made that impossible.

His defiance of his government’s own scientific experts, including “coronavirus czar” Dr. Ronni Gamzu, who recommended targeted restrictions rather than second nationwide lockdown, has seen the prime minister’s popularity plummet and spawned vociferous and sustained protests against him.

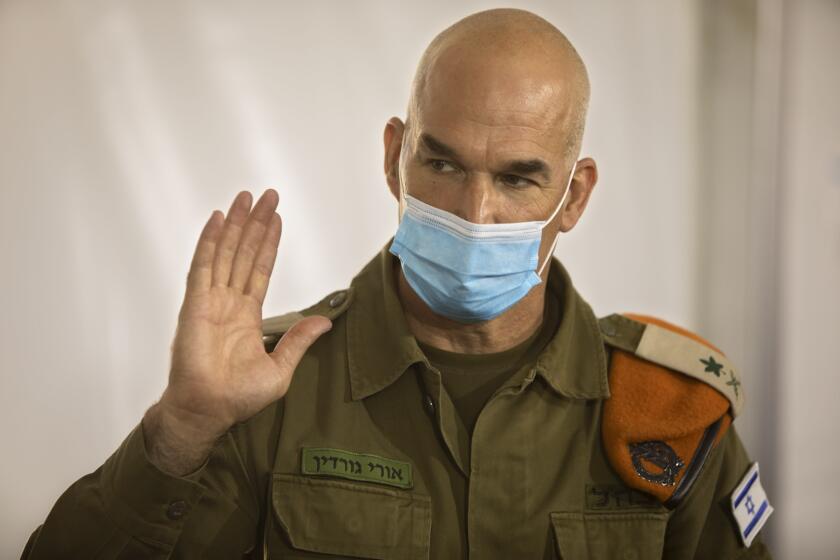

Israel is calling in its army to help as the country struggles to control one of the developed world’s worst coronavirus outbreaks.

It has also widened the growing rift between Israel’s secular majority and its super-religious minority, whom Netanyahu has so far shown little appetite for reining in.

“When Netanyahu as a person — not only as prime minister — relies so heavily on his ultra-Orthodox allies, it is almost ridiculous to think he would confront this population or its political leaders,” Plesner said.

That has led to increasing social tension that has produced some extraordinary scenes in Israel.

When Gamzu, an unflappable Tel Aviv hospital director appointed by Netanyahu only three months ago, visited the ultra-Orthodox city of Modi’in Illit on Friday, ahead of the Sabbath, residents greeted him with cries of “Evildoer!” and “Don’t close synagogues!”

After that hostile reception, Gantz, Netanyahu’s coalition partner, said: “There cannot be one law for some and another law for others. … We must be attuned to their needs, but we cannot accept anarchy.”

A wave of demonstrations is sweeping Israel against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his perceived failure to handle Israel’s coronavirus crisis.

Even as Gamzu toured Modi’in Illit, national news station Kan Broadcasting posted video of a crowded ultra-Orthodox seaside wedding in Bat Yam, south of Tel Aviv, where masks and social distancing were in little evidence. Such videos have become daily occurrences, provoking sharp criticism of the police for lax enforcement of the lockdown — and of the ultra-Orthodox for their seeming indifference to public health.

“I think we simply have to erect a barrier around [their] cities. Let’s cut them off,” Dr. Gabi Barbash, a former director of Tel Aviv’s Ichilov hospital, said in a televised interview. “Let them do what they want, and we’ll only let ambulances out to take them to hospital. It’s obvious that it will reach that situation — and maybe that’s the right way of dealing with them.”

To date, about 310,000 Israelis have been infected by the coronavirus, and nearly 2,400 have died. The ultra-Orthodox, who live in insular, densely populated communities where women cover their hair and men sport beards and long black robes, have suffered disproportionate losses.

But the haredim — long accustomed to obeying rabbis, not the government — believe that the coronavirus poses a greater spiritual risk than a physical one.

“Judaism today is togetherness. It’s the gatherings around the rabbi’s table, the lessons at the yeshiva [seminary], the rush to the ritual baths, the ceremonies and the observances,” said Israel Frey, an independent ultra-Orthodox journalist. “This is what is meant by the words ‘religious life.’

“You can keep social distance for a month,” Frey said. But for the young men who form the backbone of the haredim’s tradition-bound world, “what will they do without the yeshiva? The rug has been pulled from under their feet. They perceive it as the loss of their religious way of life.”

The coronavirus crisis threatens to shatter a delicate social and political pact between the haredim and the state that has existed since Israel’s foundation.

Several months before Israel’s 1948 declaration of independence, soon-to-be Prime Minister David Ben Gurion granted 400 ultra-Orthodox young men exemption from compulsory military service in exchange for their rabbis’ blessing on the nascent secular nation, which many viewed as a profane undertaking in the Holy Land.

Today, the number of state-supported yeshiva students has ballooned to 65,000, and Ben Gurion’s latest successor, Netanyahu, is a master of politically expedient deal-making with ultra-Orthodox leaders.

Yet even that might not be enough to save Netanyahu this time.

Israelis appear doubtful at best about the prospect of an indicted prime minister appearing in court three or four times a week, as is expected in January, when witnesses will be called to testify at his trial. Also, few Israelis expect Netanyahu to respect the power-sharing agreement with Gantz, which calls for Gantz to take over as prime minister in a year.

If the agreement is not upheld, the government appears likely to fall before the end of the year, throwing Netanyahu to the mercy of deeply unhappy voters.

Israel’s prime minister has shut down courts, ordered the internal security services to covertly track citizens using cellphone data and has incapacitated parliament.

Last week, a survey by the Israel Democracy Institute found that only 31% of Israelis trust his handling of the pandemic, and another poll found that 64% believe the second lockdown was based not on science but on politics.

“The only alliance left for the prime minister is with the ultra-Orthodox, for whose sake he’ll sacrifice us all,” Yossi Verter, a political columnist for the liberal daily Haaretz wrote Friday. “At times of relative economic and social stability, there was no problem. He paid the ultra-Orthodox whatever they wanted and passed on the burden to everyone else….

“The coronavirus crisis is bringing home the man’s leadership disability. ‘Netanyahu and the Haredim’ is the management failure of the crisis in a nutshell.”

Tarnopolsky is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.