- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Air Force lieutenant colonel left the Pentagon one day and returned the next — with a new name and a new gender identity.

Bree Fram remembers the atmosphere in 2020 as welcoming and supportive. Her colleagues brought cookies. When the Pentagon officially changed her gender in employment records, she felt her journey was complete.

Fram is one of thousands of transgender people working openly in government positions, including the Defense and State departments, intelligence agencies and various other federal branches. An estimated 15,000 transgender people work in the military alone. They say acceptance and support has surged in recent years.

But many are now worried that the broad advances they achieved over the last decade will be reversed under President-elect Donald Trump, who has likened gender transition to “mutilation,” vowed to roll back job protections and healthcare for trans workers and threatened to reimpose a ban against transgender people serving in the military.

“The mood among the community is apprehensive,” Fram said, noting she was speaking in her personal capacity and not on behalf of the Air Force.

Two transgender women in the State Department, who spoke openly with The Times earlier this year about their experiences, said after the election they no longer wanted to be identified out of fear for their safety and positions. One, a former Iraq combat veteran who transitioned later and landed at State, said she and friends now feared “becoming targets.”

Fram, a 21-year veteran of the Air Force and an aeronautical engineer whose job includes choosing the satellites that the U.S. launches into space, is a prominent activist in the transgender movement. Now ranked a colonel, she said transgender colleagues are stopping her in the hallways and bombarding her with questions and requests for advice.

“We have seen the campaign promises, the rhetoric being used about transgender people and what’s occurring on Capitol Hill as well,” she said. “So while none of us know exactly what will come to pass, there is still certainly that concern that it’s not going to be good for transgender people serving in the military.”

A group of Republican lawmakers is already attempting to bar incoming Rep. Sarah McBride (D-Del.), the first out transgender person elected to Congress, from using women’s restrooms. A leader in that group, Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.), wants to extend bathroom bans in all federal facilities nationwide.

Fears grew with Trump’s nomination of a Fox TV host, Pete Hegseth, as secretary of Defense. Hegseth has been vocal in his belief in restrictions on women in the military and the removal of transgender service members.

In 2016, President Obama lifted a ban on transgender people serving in the military. Trump reinstated it when he reached office the following year, but it was largely held up in the courts until President Biden repealed the ban. Many expect Trump to attempt to reimpose it.

Fram said she was nevertheless confident her community would persevere.

“What always amazes me about this community is despite … the many, many times we have faced adversity, it’s the resilience of this group of amazing people,” she said. “These public servants, who continue to put on their uniform every day and accomplish the mission that they’ve been given.… They are there doing the job and plan to continue doing the job for as long as they’re allowed to do so.”

No one knows exactly how far the Trump administration will go, and its efforts will again undoubtedly meet legal challenges and other resistance.

“We have seen this movie before,” said Jennifer Pizer, the L.A.-based chief legal officer at Lambda Legal, a civil rights organization that focuses on LGBTQ+ issues. “This is a group of people who are flouting the standard rules ... and looking forward to spending an indefinite time in court.”

There are several options Trump might pursue, she said.

In addition to reimposing a military ban, Trump loyalists might attempt to deny “gender affirming” healthcare, forbidding federal funds or insurance plans to be used in procedures that facilitate transition, including hormone therapy and plastic surgery.

Republicans have added a rider to the must-pass defense authorization bill, forbidding such care for minors. That would have an impact on the children of service members.

And already, numerous states ban such care for minors in the civilian realm, an issue currently being reviewed by the Supreme Court.

When he first enacted the military ban, Trump said having transgender people in the armed forces was expensive. A 2016 study by Rand concluded that transgender healthcare added less than 0.1% to the health budget.

At the State Department, numerous policies, as well as union rules, are in place to protect transgender and gay diplomats and employees. But such policies could be subject to new executive orders or reversals.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the State Department pursued a hunt for gay and lesbian employees, civil servants and diplomats known as the Lavender Scare. They were routinely dismissed; many who hung on had to work in the closet. Some of the black-balling continued into the 1990s.

At the same time, the military and other federal agencies have often become national testing grounds in matters of inclusion and diversity.

For the record:

12:33 p.m. Dec. 19, 2024A previous version of this article reported that the Army was desegregated by President Franklin Roosevelt. President Truman issued the desegregation order.

President Truman desegregated the Army after World War II. Later, women were given broader roles, including, now, in combat.

In 1993, President Clinton took a first step toward lifting the ban on gays and lesbians in the military — a ban that was ended entirely in 2011.

Today, the State Department has teams dedicated to advocating for LGBTQ+ rights abroad, through embassies and sometimes in countries where homosexuality is criminalized.

In 2011, Robyn McCutcheon, a diplomat, trained astronomer and Russia expert, became the first person to transition while posted at a U.S. Embassy, during her tenure overseas in Romania.

“It is our collective responsibility to ensure transgender persons can live full lives, without fear of harm,” Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken said just last month. “The United States is committed to fighting for a world that accepts and respects transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming persons.”

“Until then,” he said, “we proudly advocate to end transphobic discrimination, violence and homicide.”

It is not clear these programs would continue under Trump and his nominee for secretary of State, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.).

Logan Ireland, a Texas-born transgender man who is an officer with the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, counsels others in the transgender community who want to join the military, with an added urgency after the election.

“You’re on this mission for a reason,” he said he tells them. “Continue pressing forward with your journey to serve in uniform.... A ban is not in effect yet, and we will not know if, or how, it might take shape.”

Ireland, speaking from Hawaii where he is stationed, said the struggle thus far “has taught us how to fight, resilience, integrity. I have to remain positive.”

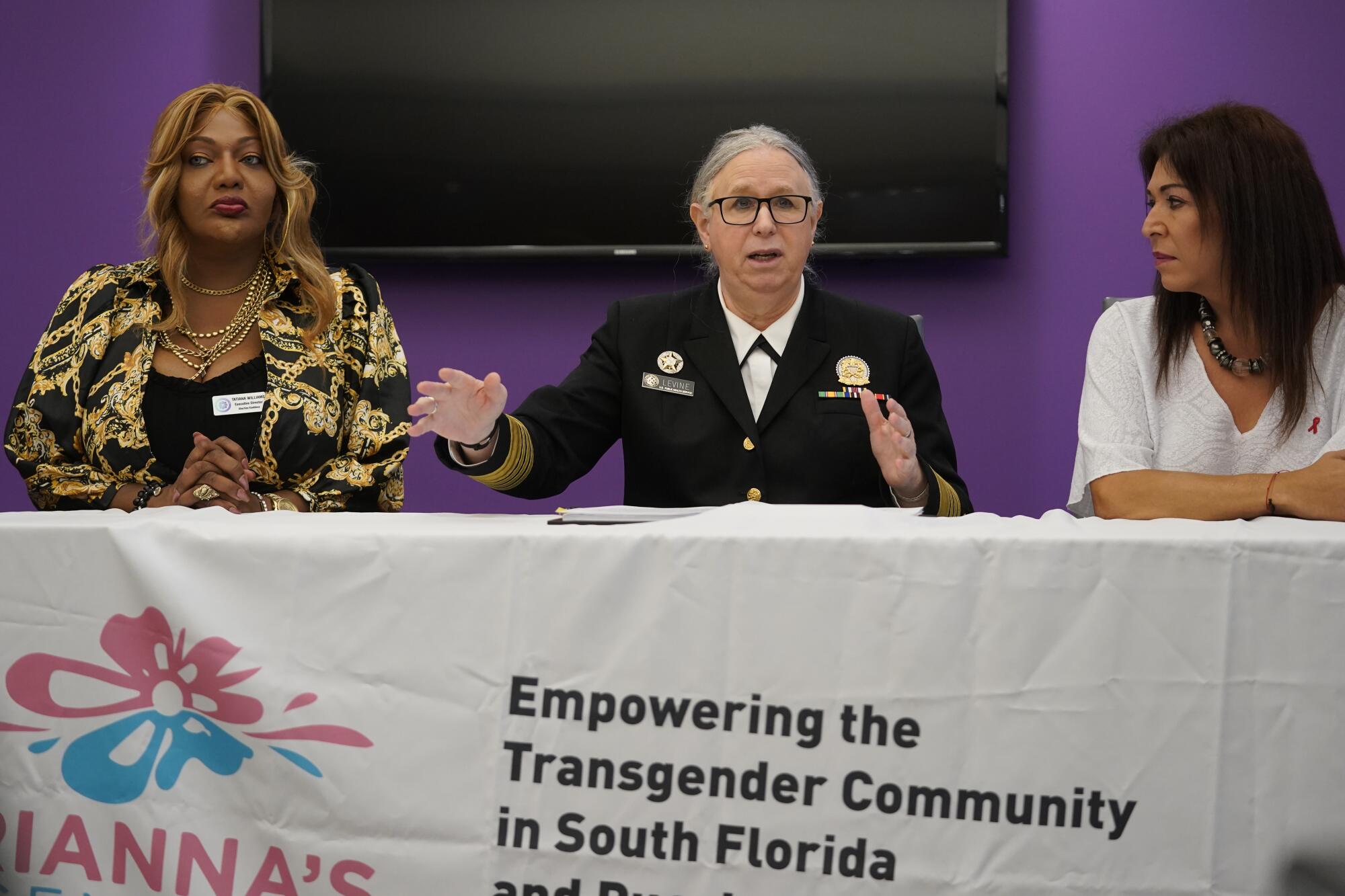

Rachel Levine is often described as the most senior transgender person in the U.S. government, the first Senate-confirmed official who is transgender. She is the assistant secretary of Health in the Department of Health and Human Services. She is a long-time public activist for trans rights, and served as a grand marshal in last year’s gay pride parade in Washington.

Levine, 67, a former state secretary of health in Pennsylvania, had already transitioned when Biden nominated her to the HHS job. She overcame resistance from GOP senators, including Republican Rand Paul of Kentucky, who attacked her for her support for gender-affirming medical care and grilled her on whether transgender women should be allowed in women’s sports.

“There has been a lot of pushback against the broader LGBTQI+ community that has nothing to do with science and nothing to do with medicine,” she said. “And faced with that pushback, I find joy in my work. It makes me want to work more for health equity.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.