How the paths of Saudi Arabia’s crown prince and the world’s richest man crossed

- Share via

It was a soft early-spring night in Los Angeles, and the dinner party’s guest list included a young, fabulously wealthy monarch-in-waiting. And a household-name tech mogul who was fascinated by space travel and regularly topped the world’s-richest list.

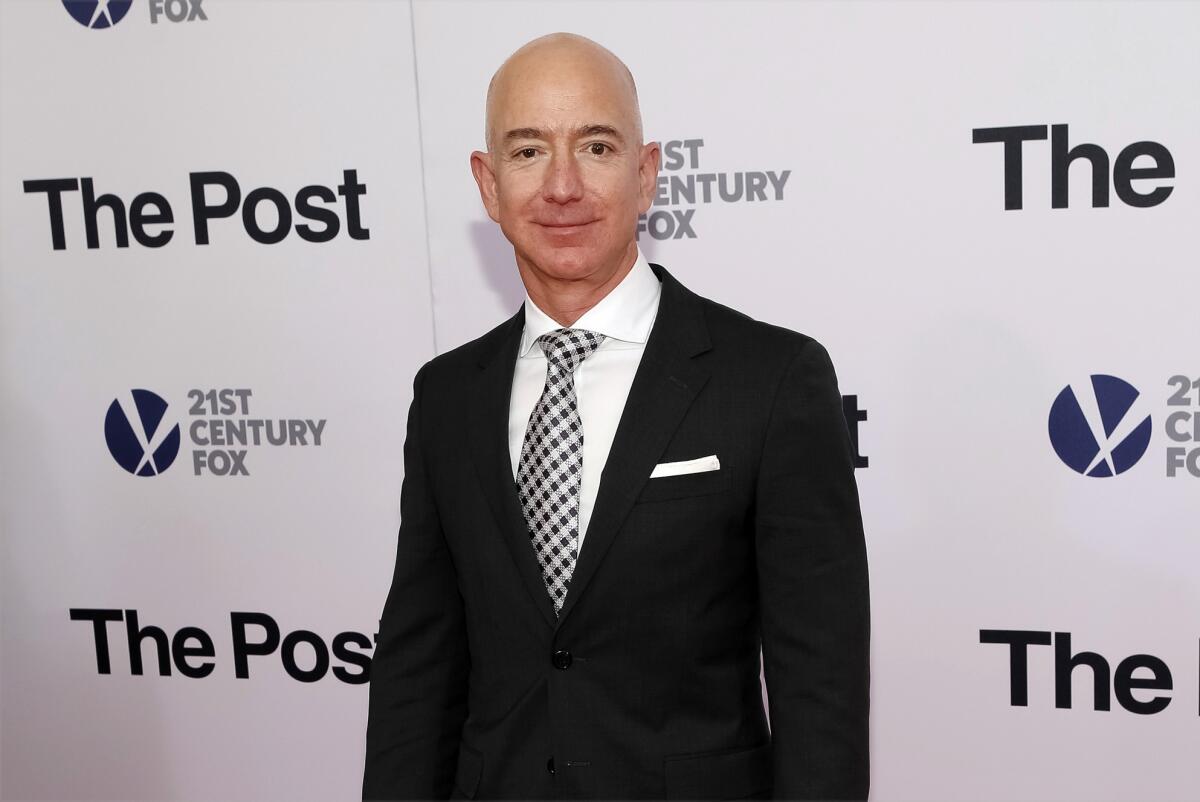

Sometime during that April evening in 2018, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who was in town to mingle with celebrities and attract Hollywood investment, apparently swapped phone numbers with Jeff Bezos — an encounter that would prove fateful for both men.

Since then, the crown prince has been implicated in the gruesome killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a onetime Saudi palace insider who penned scathing opinion pieces about the kingdom’s leadership for the Washington Post, which is owned by Bezos.

Bezos, meanwhile, endured a high-profile divorce that became tabloid fodder not only because of the billions of dollars at stake, but because of the revelation of intimate texts and photos, the hallmarks of an extramarital affair.

Now, like fizzing wires, these two narrative arcs have crossed, with the allegation — flatly denied by Saudi officials, but given credence by United Nations investigators — that a WhatsApp account personally used by the crown prince became a conduit for malware used to hack Bezos’ phone.

The prospect of blackmail has drawn increasing attention to the crown prince, who in recent years has emerged as both a telegenic reformer and a royal inclined to palace intrigue and vengeful schemes farther from home. His style — plotting power with few boundaries — has found an ally in President Trump, who has repeatedly seemed an apologist for the kingdom even after Khashoggi’s death and the December killing of three U.S. sailors by a Saudi aviation student at a base in Pensacola, Fla.

The confrontation between Mohammed and Bezos carries larger implications for the oil-rich kingdom’s fitful efforts to modernize its conservative society and monarchy, for privacy concerns fueled by the worldwide tech industry, and for growing fears over the cyberstalking of exiled dissidents by repressive regimes.

It also comes against a volatile regional backdrop, with Sunni Muslim-dominated Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest oil producer, engaged in a Cold War-style standoff with mainly Shiite Iran.

Amid a multifront Mideast struggle for influence by the two rivals, Saudi Arabia’s years-long battle with Shiite rebels in Yemen – a conflict of which the crown prince, with U.S. backing, was a key architect — has become a humanitarian catastrophe.

The hacking contretemps could even touch upon U.S. national security, in light of Mohammed’s much-reported role as a WhatsApp interlocutor of Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and a senior White House aide. There is no indication that Kushner’s phone was ever compromised, but critics have repeatedly raised concerns about his security clearance, and about the president’s own lapses in safeguarding sensitive information and his casual use of unsecured personal devices.

Trump, whose first foreign trip as president was to the Saudi capital, Riyadh, has long fended off sharp congressional criticism of the kingdom. And he has aimed furious personal attacks at Bezos, brushing aside the paper’s longstanding insistence that its owner does not dictate editorial policy.

Mohammed’s international reputation is still besmirched by the Khashoggi killing, which the CIA believes took place with his knowledge. But analysts say the opaque nature of Saudi palace politics makes it hard to assess the effect at home.

“I don’t think anybody outside the kingdom can answer that,” said James Gelvin, a professor of modern Middle Eastern history at UCLA.

Speaking as the country’s de facto leader, the 34-year-old last year accepted broad but vague responsibility for the journalist’s killing. But he denies ordering Khashoggi’s slaying and dismemberment inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, in October 2018, which were captured in harrowing audio recordings, replete with last gasps and the chilling hum of a bone saw.

Five Saudis, whose identities have not been disclosed, have been sentenced to death in connection with the killing, according to the Saudi government.

The crown prince, who is in line to inherit the throne from his ailing octogenarian father, King Salman, has worked hard to craft the image of an innovator and reformist who hopes to diversify the kingdom’s energy-dependent economy. His 2018 U.S. tour, in which he hobnobbed with celebrities, tech leaders and corporate titans, was meant to be a showpiece for those ambitions.

But at home, policies intended to telegraph a progressive stance — greater freedoms for women, opening the country for tourism, defanging the religious police — have coincided with harsh repression of dissent. Human rights groups and some Western governments have spoken out against the imprisonment and alleged torture of women’s rights activists and others.

Even amid the outcry after Khashoggi’s killing, international businesses have gone ahead with Saudi investments, though with less fanfare. Before his death, Amazon Web Services, the company’s cloud-computing division, was considering the construction of large data centers in the kingdom, but the Post reported last year that those plans had stalled.

Although Mohammed is still viewed as politically toxic in some circles — last fall, with the crown prince due in New York for the U.N. General Assembly, the New York Public Library canceled an event co-sponsored by one of his personal charities — he is welcomed at international gatherings, particularly finance-themed ones, and Saudi Arabia is set to host the Group of 20 summit this year.

Nikolas Behar, a San Diego-based cyber security expert, said the alleged hacking may make investors rethink potential Saudi dealings , including in the crown prince’s Vision 2030 plan to pivot away from oil and diversify the economy.

“What the tech industry does will be contingent on what the U.S. response will be,” Behar said. “People in the industry will be thinking ‘Are we going to get hacked, and is the money worth it?’”

An allegation centered on reckless use of technology is awkward, to say the very least, for an overall Saudi business strategy undergirded by the kingdom’s push to modernize its tech infrastructure and market itself as a mecca for startups and entrepreneurship.

“Everything will have a link with artificial intelligence, with the internet of things — everything,” the crown prince told Bloomberg in 2017 while touting Neom, a $500-billion megacity-of-the-future project. Last year, the Saudi state established bodies such as the Authority for Data and Artificial Intelligence in order to boost the kingdom’s information-processing capabilities.

The explosive news of the suspected hack of Bezos’ phone, first reported by the Guardian newspaper and the Financial Times, was based on a forensic analysis commissioned by the Amazon chief. That analysis by the advisory firm FTI Consulting, the reports said, concluded with “medium to high” confidence that the malware used was introduced via a video file sent using a WhatsApp account used by the crown prince.

Early last year, the Amazon chief disclosed that the parent company of the National Enquirer had threatened to publicize private texts and pictures pointing to an extramarital affair. He fought back against what he characterized as a crude blackmail attempt by acknowledging the existence of the material in a post on the website Medium.

His security advisor, Gavin de Becker, at the time voiced suspicions of Saudi involvement. The Wall Street Journal reported Friday that prosecutors have evidence suggesting Bezos’ girlfriend gave her brother text messages that were later sold to the National Enquirer.

The findings by FTI Consulting were amplified by a pair of well-known U.N. rights investigators, Agnes Callamard and David Kaye, who said the crown prince apparently sought to “influence, if not silence” critical coverage of Saudi Arabia by the Bezos-owned Post. Khashoggi’s killing came nearly six months after the May 2018 hack, but by then the 59-year-old writer had been publishing caustic opinion columns for months in the newspaper.

The U.N. experts also alluded to the kingdom’s role in extensive social media campaigns targeting critics, and cited reports from exiled dissidents who say they were also hacked with technology similar to that used against Bezos.

The Saudi government reacted with indignation. Its embassy in Washington tweeted last week that reports it was behind the hack were “absurd.” It called for fact-finding, but did not say by whom.

Bezos offered up an indirect but pointed rejoinder, with a Twitter post that showed him posing with Khashoggi’s Turkish fiancee, his hand resting on a memorial stone bearing the writer’s name. It was captioned “#Jamal.”

Times staff writers Etehad and King reported from Los Angeles and Washington, respectively. Staff writers Nabih Bulos in Beirut and Stacy Perman in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.