- Share via

It wasn’t like Marlon Brando to go spilling his private beans to the world about the life he had spent his years protecting.

But about Tetiaroa — the Tahitian atoll of his childhood yearnings, and the refuge of his adult life — he did.

We were friends for the last years of his life, and one day in 1997, at his house on the crown of Mulholland Drive, he said to me something he’d never said before: Take notes. He’d tell me about his private atoll, Tetiaroa, and one far-off day, he wanted me to explain to all of you what the place meant to him, and what he wanted it to become after he died.

His hope, his plan, was for Tetiaroa to become an ecologically responsible tropical resort, but more vitally, a nature preserve, an open-air experimental science laboratory, a “university of the sea,” all to serve the place and the planet.

Marlon Brando, a two-time Academy Award winner who spent much of his career shunning the Hollywood establishment yet earned its enduring admiration through muscular, naturalistic performances that transformed the craft of acting and led peers and critics alike to hail him as the finest actor of his time, has died.

Now, I know that “eco-resort” is a paradox. The smallest human act can take a toll on the planet. And the carbon footprint of the rich can be Sasquatch-sized. But Marlon was paradoxical himself, so why should his vision not be practicable and paradoxical, as well?

And what do you know? I went to see it in action, and it’s working about as well as he could have hoped.

In the faraway loveliness of the South Pacific, the Brando, the high-end private resort that carries his name, is carrying out some useful, cutting-edge technology that Marlon envisioned so many years ago.

April 3 will be his 100th birthday; July 1 will be 20 years since he died. By the time we talked about Tetiaroa, he had not seen it for some time, but it was always on his mind. It was also in his mind as the place where he liked to say he felt most himself, which is to say, no one special:

“Just a visitor, like thousands of other people who had been, and lived, who were born and died on Tetiaroa. So I was part of the passing parade, just a jeering, japing clown with a one-way ticket to eternity, like the rest of them. Like the rest of us.”

Marlon grew up in Nebraska and Illinois, his restless spirit and relentless curiosity too big for flesh-biting winters and small-town constraints. In the military school that was meant to bring him to heel, he hunkered down in the library.

“I loved reading the National Geographic. It would take me far afield, to places I’d never been, never even heard of. … The culture which fascinated me most, which seemed most attractive to me, was the Polynesian culture. … Here was this lovely and timeless place before me, in the pages of a magazine, and I thought, ‘One day, I’m going to go there.’”

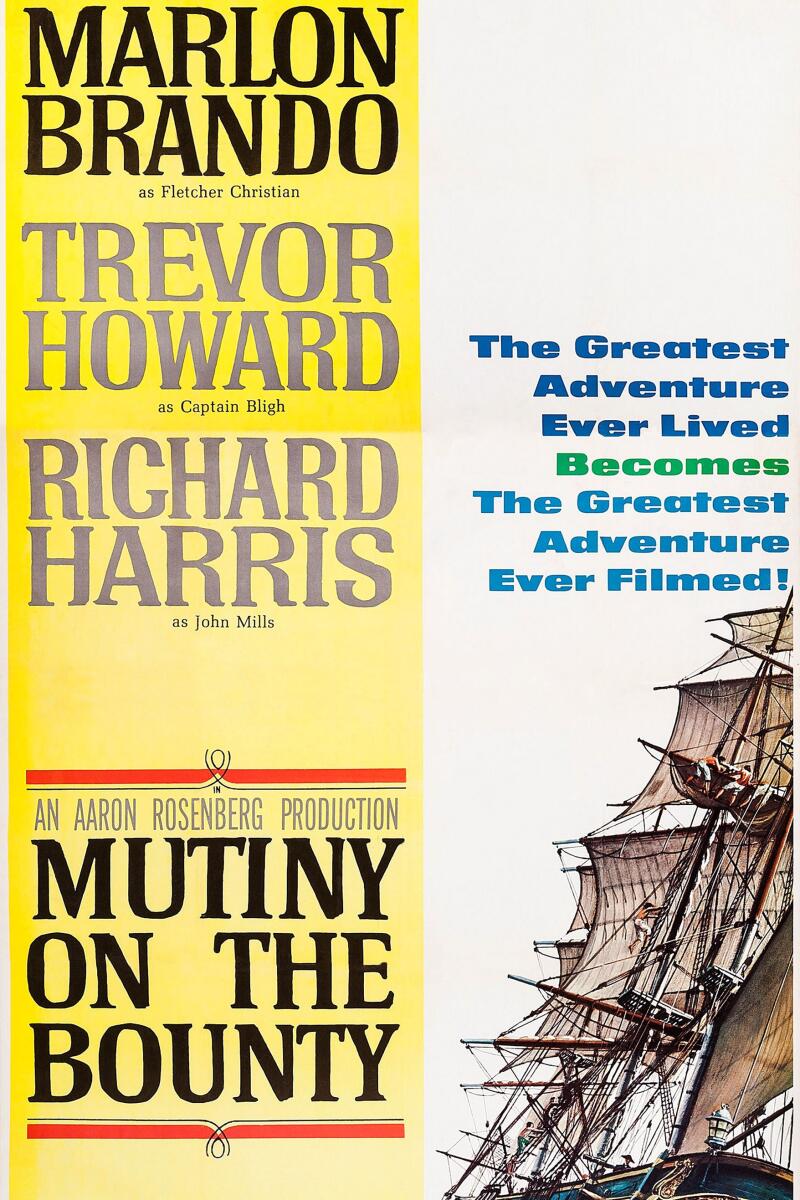

Two decades later, he reached his dream destination. In 1961, he was in Tahiti to film “Mutiny on the Bounty.” He was Fletcher Christian, an officer in His Majesty’s 18th century navy, gussied up in gold braid and buttons for the role, and he couldn’t have been more eager to shed the suit and the buttoned-up culture it stood for.

A U.S. poster for “Mutiny on the Bounty” from 1962. (LMPC via Getty Images)

Marlon Brando on the set of “Mutiny on the Bounty.” (Sunset Boulevard / Corbis via Getty Images)

This was his boyhood reverie made real. Within a few years, Marlon had started a Tahitian family and managed to buy Tetiaroa, the wild and sacred atoll about 40 miles from the capital city of Papeete, made up of a dozen small islands — motus — encircling an opalescent lagoon.

And now you can break out the thesaurus. Anyone who sees Tetiaroa labors for superlatives and synonyms: magical, enchanting, gorgeous, possessing every earthly and unearthly tone of blue, its wind and its water so mild and sweet that maybe this is what the womb felt like, and what heaven will.

“The first night after I’d bought it, I put my head on a coconut I’d worked into the sand and used for a pillow. It’s wonderful to sleep naked on the beach, because the wind comes over you and gives you caresses like you’ve never been caressed in your life. … I very quickly realized that I didn’t own that island; the island owned me. … Nothing that I thought or felt or hoped for or experienced or knew would have any more significance than the grains of sand that I was lying on, and it gave me deep comfort. Most people, certainly many people, would be frightened by that. … I’m a person who loves the desert, loves the emptiness, and loves the sky, loves lying on the beach and looking at a hemisphere of stars … “

What was his and his alone is now a destination for those who can afford it. Among its guest list past, the Obamas, Beyoncé and, supposedly, the honeymooning Pippa Middleton, sister of the Princess of Wales. Britney Spears was there while I was, but the staff are so discreet that the only way I knew she was there was that she posted about it herself. To that end, the Brando asks guests to sign a gentlemanly notice that people come seeking “complete privacy and freedom,” and so we all commit to “refrain from any encroachment” on that, including taking any pictures or “any photographic images of other guests outside your party.”

That’s part of the onstage Brando resort. The backstage Brando is what mattered most to Marlon. Before he died, he collaborated with Richard Bailey, chief executive of the Pacific Beachcomber French Polynesia luxe resort company, to make it so. And after Marlon died, Tetiaroa’s ownership went to a trust to benefit his children. Bailey’s firm has a 99-year lease on two motus — about 10% of the atoll’s land — with the rest preserved from any construction.

The Brando opened in 2014, 10 years after Marlon died, and it took every one of those years to get it working with its odd-couple combo of tranquil, lavish resort, inventive and challenging green systems, and respect for Tetiaroa’s deep cultural and ecological rarity.

“It’s not just about green,” Bailey told me. “Anyone can do green; it’s just a question of will. The driving factor for us is remoteness and isolation.”

That, and as much sustainability as possible. Food autonomy on such a property is out of reach. As Bailey pointed out, “Even the ancient Tahitians traded between islands.” But there are other kinds of sustainability, and they are apparent from the window of the small Air Tetiaroa plane.

Approaching the landing strip, most passengers are oohing and aahing at the blue view and beckoning palms, and I’m looking at the solar panel array fringing the landing strip — thousands of them, and a couple of big storage batteries for sundown energy. There are generators that use biofuels and diesel as needed, but solar is the big player in the Brando’s energy future.

In this part of the world, the biggest single energy appetite is for air conditioning. For most of French Polynesia, that means fossil fuels brought in at great cost from elsewhere. Not in Marlon’s vision.

Our mutual friend Ed Begley Jr., the environmentalist and actor, told me recently that Marlon “ wanted [Tetiaroa] to be a very low impact in every way — carbon footprint, protection of wildlife, everything. He wanted to spread the message of what was possible, what one could do on an island like his, or wherever we live, that it was possible. He just always loved that cutting-edge stuff.”

Marlon subscribed to science magazines and technical journals. He learned about Tetiaroa’s water tables and soil quality and flora and fauna. In the early days, he applied himself hands-on to Tetiaroa’s plumbing challenges. In his later years, any plumber called to the Mulholland Drive house would find himself being followed around by Marlon, who’d also peer underneath the sinks alongside him and ask about torque wrench brands and hose bib fits.

He once summoned Begley up to the house to work out the practicalities of keeping electric eels in the swimming pool to generate power. There were none. “You’re not going to have enough current to light up a child’s lightbulb project at a science fair,” he informed Marlon, who did not take such negation well.

But not all of Marlon’s brainstorms were so outré, and here is the Brando’s principal innovative success. Tetiaroa has the world’s largest SWAC system, a seawater air conditioning loop. It provides the air conditioning for almost everything but food storage, with negligible ocean impact.

For the record:

11:12 a.m. March 21, 2024Officials with the Brando resort say they provided an incorrect figure — 400 meters — for the length of the pipe through the atoll’s reef. The actual length is 930 meters.

Here’s how it works: A 930-meter pipe through the atoll’s reef follows the ocean floor, and the natural ocean pressure itself brings up the cold seawater, occasionally using supplemental pumps. After the “heat exchange” process — a kind of “bundling” where the cold seawater chills pipes full of warmer freshwater — the seawater is sent back into the ocean a degree or two warmer than it arrived.

Once the seawater reaches land, the pipes carrying it cozy up to parallel pipes carrying freshwater. Via contact with titanium plates, the freshwater also gets frosty, and that chilled water loop sends its cold energy into the atoll’s air conditioning system.

I saw this in a small experimental form on Bora Bora in 2005 and now here it was, scaled up and doing the job. The technology is geographically limited; the recipe starts with a coast and deep, cold ocean water. A hospital in the Tahitian capital is now using it too. Tetiaroa’s SWAC cost about $12 million to create, and it’s breaking even this year, so it’s pretty much gravy hereafter.

On my first visit, in 2005, Tetiaroa was beyond wild. Years before, Marlon planned a self-sustaining community that never came to pass, in part because most of the amenities he did build — bungalows, a bar — were whipped away by a tropical storm.

The mosquitos, as I remember, were as vicious as the Luftwaffe. And that’s another Marlon mission accomplished. A breeding program has virtually eradicated mosquitos on Tetiaroa. The bloodsuckers carry devastating diseases and, let’s face it, tourists come looking for fun, not infection.

So, using research by the French Polynesian Institut Louis Malardé, Tetiaroa breeds and releases millions of male mosquitos whose bacteria makes the female bloodsuckers effectively sterile. There’s a photo of a visiting Barack Obama releasing some of the male mosquitos.

The institute coordinates the mosquito disappearing act with the nonprofit Tetiaroa Society, another of Marlon’s dream operations. It recruits students from as far off as UC Berkeley and the University of Washington for the work of protecting habitat and wildlife. It’s pretty much rid the atoll of the rats that kill native ground-nesting birds and the rare green sea turtles that now thrive by the thousands in the Tetiaroa sanctuary. [The society also protects the turtles from human rats — the poachers who historically raided the turtles’ nesting grounds.]

Staghorn coral spotted on a Teriaroa Society tour. (The Brando)

Green sea turtles thrive by the thousands in the Tetiaroa sanctuary. (The Brando )

All of this requires rigor and expense. Even before you board the plane for Tetiaroa, a bio-inspection point in Papeete intercepts any items that could endanger Tetiaroa’s native ecosystem. My scientist friend Frances had to hand over her pear; bananas, which can carry a contagious plant ailment, will not be found in the atoll’s fruit baskets.

The Brando offers its guests lagoon boat tours around the motus, led by savvy young biologists who are incidentally all in for the recreational life aquatic here too. Ours pointed out fluffy booby hatchlings in the low branches of trees on one motu, and showed us up close the massive coconut crabs whose kind is coming back from the vanishing point.

The best tour for me was the “green tour,” a backstage look into the environmental operations. It too is a kind of theater, but one that raises the curtain for guests on some of the Brando’s priorities. Two massive food bio-digesters reduce food waste to compost in 24 hours. The recycling center sorts 29 varieties of objects, and manages to recycle something like half of them, saving the cost and carbon footprint of sending them off-island. Glass is ground into sand to fill in off-the-path areas. Coffee grounds are dumped out of coffee pods and used for compost. Rainwater feeds the atoll’s toilets.

In each villa, the television’s home-screen video is about the responsibilities to Tetiaroa’s environment and culture, and each villa has bins for recyclables. You won’t see that at your Ritz Carltons.

My second visit, last fall, was altogether different from the first. Take it as a given that there is no such thing as a budget visit to the Brando. My three-night stay, with Frances, was a one-time gift to me as one of Marlon’s friends-and-family circle. The villa rates start at about $3,000 a night, depending on the season.

At any one time, the Brando usually has 70 to 90 visitors, and a rotating staff of about 200, along with energy workers, Tetiaroa Society researchers and specialists like the venerable beekeeper who tends the atoll’s 70 hives for their distinctly flavored honeys.

Guest services are suitably thorough and unobtrusive. Still, for that kind of money, even Brando guests don’t always get what they want; the island’s needs often come first. Sergei Petrov, the duty manager while I was there, told me that some people will insist on steak, not fish, “and that I can do.” But no, they have no bananas, nor imported Norwegian water, nor Mylar balloons for a birthday; substitutes will be courteously suggested.

Marlon lived well but not diamonds-and-Rolls-Royce fancy, and he’d be bemused by some of the flashier guests who take routine R&Rs here. I wonder how many would have passed his test. Marlon loved to test people. Be invited to his Tetiaroa and you would be watched by him, to see whether you too shared his nirvana at its isolation, or whether instead you soon got edgy and full of angst, so far from concrete and gasoline power.

“We can study one place like Tetiaroa in microcosm and use that model. … Whatever else I do there, the isolation is something I wish to preserve, because more and more, the quality of ‘less and less’ is at a premium in this life. … One of the things I want to do is teach people the value system that’s innate in Polynesian culture … the Tahitians, they just accept what is there.”

He taught me a Tahitian word, fiu, a kind of hand-flip word meaning “enough,” or “fed up.”

He might have used it for what he thought of acting. By the end of his life he had not much use for his extraordinary film legacy, nor for the phenomenal praise he got for having changed the art. He dismissed it, cavalierly and even cruelly, as “lying for a living.”

Fiu.

But the legacy of Tetiaroa that he has added to its long and legendary story — that, I think, would have made him proud.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.