Postcards From the West: The Grand Canyon, just as the Kolb brothers pictured it

Mather Point, the Bright Angel Trail and more from the South Rim of Grand Canyon National Park.

- Share via

Reporting from GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK — They were just a couple of greenhorns from Pittsburgh, but the Kolb brothers knew the greatest photo op in the West when they saw it.

It was 1902. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway had just begun service to the Grand Canyon. The Kolbs gaped at the South Rim and bought the only photo studio for miles around. Then they set up shop at the head of the Bright Angel Trail, snapping tourists on muleback.

Then as now, the saddled-up tourists and their mules would clip-clop down the switchback trail into the vast chasm, denying vertigo, approaching infinity.

By the time those tourists returned that night to the rim, the Kolbs would have prints to sell them — proof of the travelers’ valor and the canyon’s desolate beauty, all in one frame.

An empire was born, as was one way of seeing the Grand Canyon.

If you show up on the South Rim in 2015, as Times photographer Mark Boster and I did recently, you have to wonder what the Kolbs would say. The mules still clomp down the hill, tourists fidgeting in their saddles. The Kolb studio, grown to a five-story structure, still stands with an odd, smallish window on its west wall, facing the trail. For more than 65 years, that’s where the photographer, usually Emery Kolb, snapped the group shot of the mule riders, including former President Teddy Roosevelt and his group in 1911.

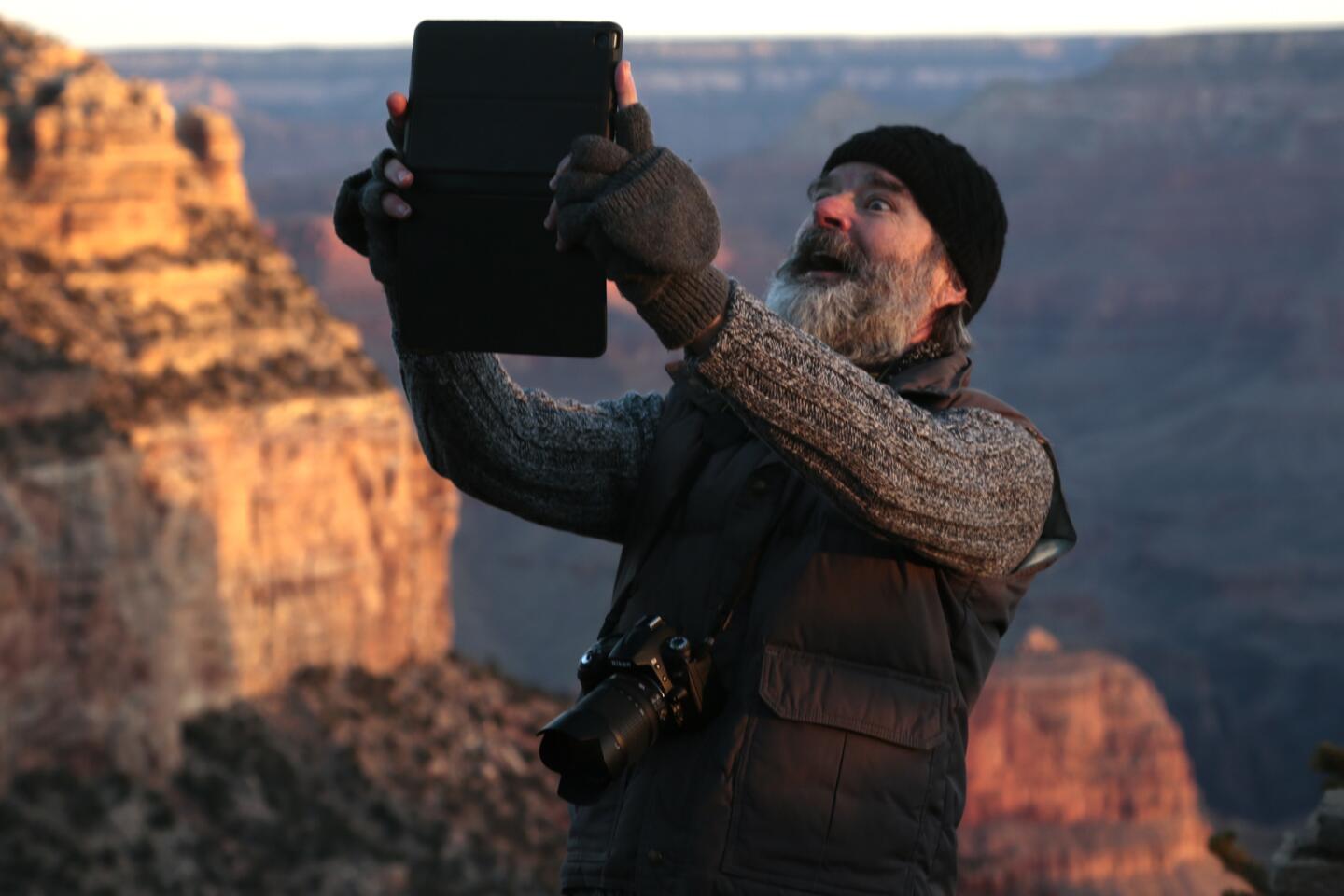

But nobody works that window now because we tourists have our smartphones, GoPros, DSLRs and tripods. Instead of letting somebody frame the canyon for us with a piece of pricey equipment, we can do it ourselves — if only that guy with the selfie stick would move a few feet.

Over our four days at the canyon in March, we spent lots of time dodging selfie sticks, thinking about image makers and chasing images ourselves.

We rose in bitter-cold darkness to catch sunrises at the Bright Angel trailhead and Mather Point (which loses color and gains crowds as the day goes on). We lingered in a stiff breeze for a Mohave Point sunset, hoping a miracle gap might open in the wall of clouds. (It didn’t.)

We squinted and cheered through a golden sunset at Desert View, where the river is visible at the bottom of the canyon. And we eavesdropped at the mule stables while guides saddled up the morning’s riders.

“This is not a pony ride at the county fair,” a guide told the rookies one morning. “Two hours from now, you’re all going to be crippled. Except the kids.”

Actually, we eavesdropped in a lot of places.

“My thumb’s so numb I can’t text,” complained one shivering man at Mather Point.

“Obviously, in New York, they don’t know what ‘RV parking’ means,” said a peeved woman, confronting a BMW (with East Coast plates) in the wrong part of the Visitor Center parking lot.

“I’ve done a lot of hiking, and my fear of height has pretty much gone away,” said Casey Hinson of Houston as he posed on a small ledge above a deep chasm.

I never hiked down more than 11/2 miles below the canyon rim, but I probably spent five hours on the Bright Angel Trail (using crampons, because there was still plenty of ice). The view was almost paralyzing, and it changed with every step. As I trudged and lingered, I imagined Emery Kolb, 5 feet, 2 inches and full of cantankerous energy, shouldering past me.

Emery was the younger brother. Biographer William C. Suran writes that he was shrewd, scrappy and 21 when the business was born. (Ellsworth, adventurous and easygoing, was 26. He arrived first, in 1901.)

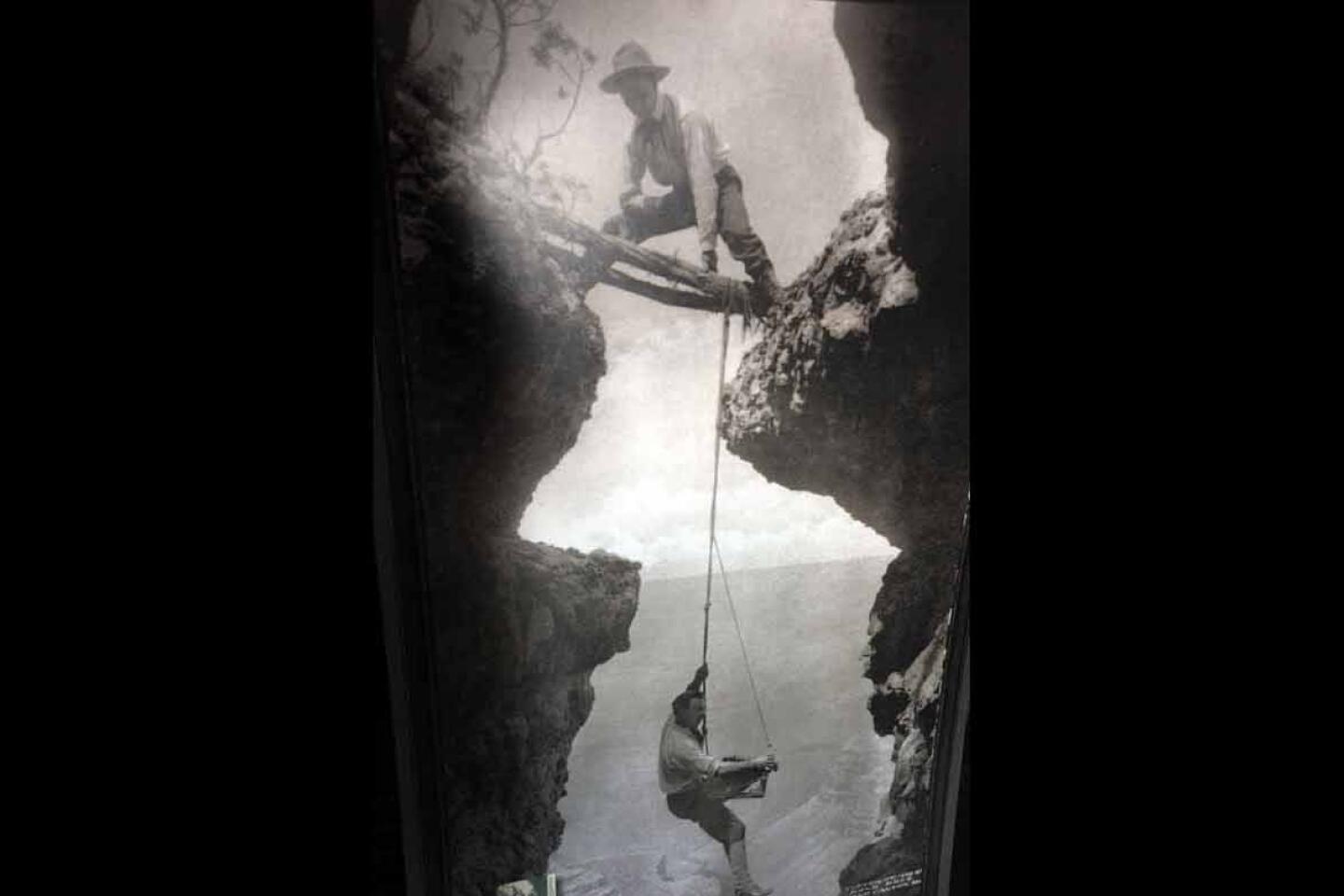

In the early years of the studio, after Emery snapped the tourists at the trailhead with a 5-by-7 camera, he would hike 41/2 miles down the trail to Indian Garden, halfway to the canyon floor. Why? Because it had the nearest running water, and that’s where his rustic darkroom was set up. Once his negatives were processed and prints were made, Kolb would rush back up the trail to beat the returning tourists.

That routine might seem enough to keep a photographer busy. But in the fall and winter of 1911-12, the Kolbs got hold of an early movie camera and decided to film themselves following the long, death-defying route of John Wesley Powell’s first descent of the Colorado River. Starting on the Green River in Wyoming, passing through the canyon and finishing at Needles, Calif., the two (with two helpers at different times) spent 101 days on the river, surviving hundreds of rapids.

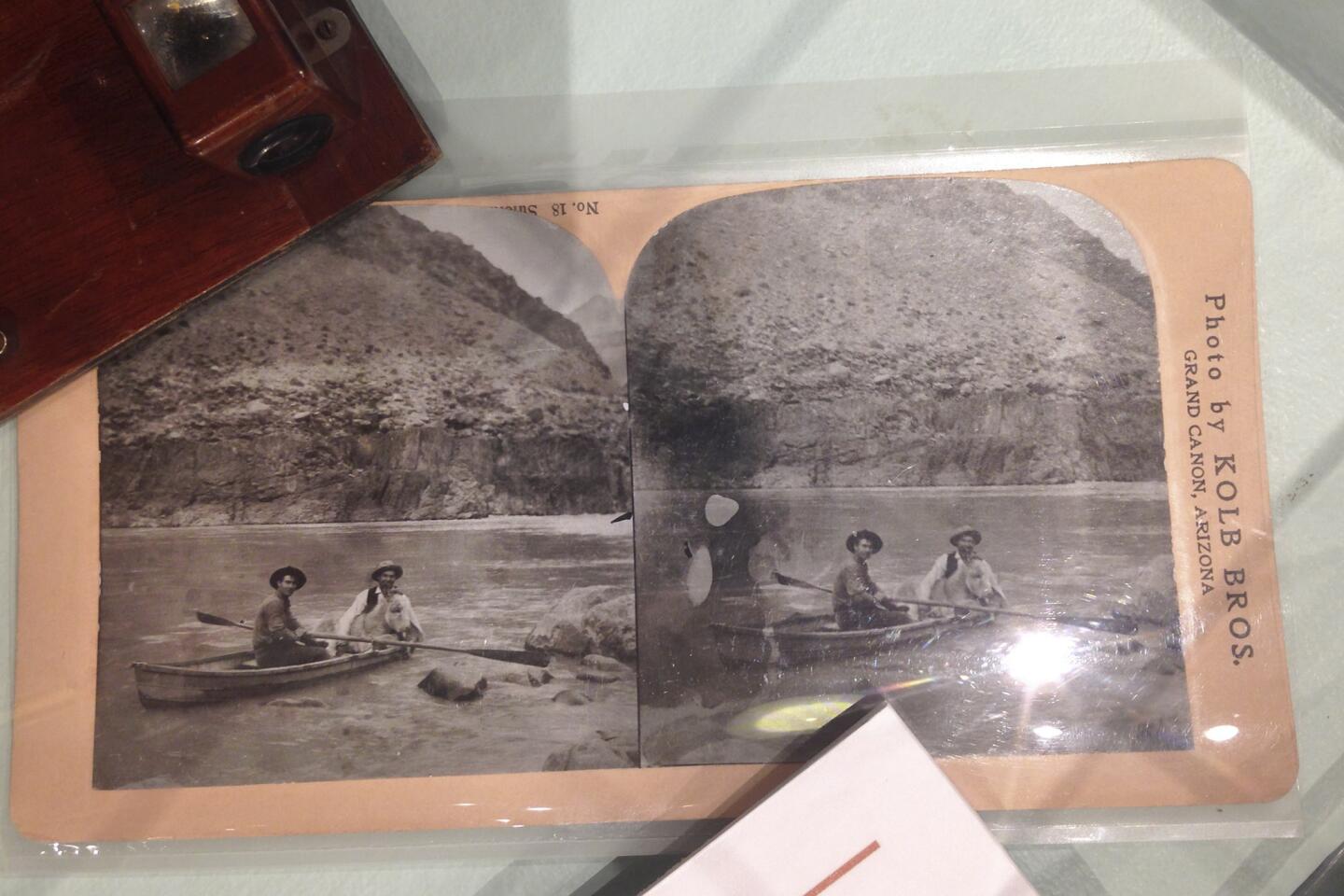

Spliced together, their footage amounted to the first motion picture showing the Grand Canyon — and it may have kept the company afloat. In 1914, the Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Co. had architect Mary Colter build a rival photo studio to grab the Kolbs’ business.

But the brothers counterpunched. They added an auditorium to their studio and in 1915 started screening their movie nightly, with live narration. It was a hit.

Ellsworth moved to Los Angeles and sold his share of the business in 1924, but Emery continued to photograph the mule strings through the window and narrate the film nightly. He lived in the studio building with his wife, Blanche, and their daughter, Edith.

Edith grew up and Blanche died in 1960, but Emery stayed at it. As late as 1969, at 88, he was still shooting two mule strings a day. By late 1976, when Emery died at age 95, the film had been running nightly for more than 60 years, and Kolb had photographed an estimated 50,000 mule strings. (If you caught the Grand Canyon parts of Ken Burns’ 2009 PBS series on the national parks, you may have seen some of his footage.) Meanwhile, the cliff-clinging Kolb building had surpassed 50 years of age, which officially made it part of Grand Canyon history.

Now the Grand Canyon Assn. uses it as a gallery and gift shop (still in competition with the Lookout Studio down the path). The old auditorium is filled with an exhibition on the Kolbs.

Its private residential rooms are “too delicate” for frequent tours, studio manager Robb Seftar said, but he was willing to show me around, including the room with the view where Emery Kolb often lay in his last months and the little window where he used to take the mule-string shots. We also prowled around the adjacent darkroom, built to succeed the one at Indian Garden. It was still full of the photographer’s tools.

This a strange thing to admit after four days in panoramaland, but the Grand Canyon location that lingers most vividly in my senses today is the little window and the cramped, viewless darkroom where Kolb framed the canyon for so many American travelers. At least 40 years after the old man developed his last picture, it still smells of fixer.

Notable dates in the history of the Grand Canyon

Navajo, Hopi, Ancestral Puebloan, Southern Paiute, Zuni, García López de Cárdenas, John Wesley Powell, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, Ralph Cameron, Ellsworth Kolb, Emery Kolb, Santa Fe Railway, Fred Harvey Co., Charles Whittlesey, Mary Colter

5 million years ago: Water and wind begin to deepen a crevice that will become the route of the Colorado River. Those forces eventually will carve a nearly 300-mile-long canyon up to a mile deep and 18 miles wide.

12,000 years ago: Somebody leaves artifacts that will later be found by scientists. Over time, 11 tribes have been associated with the canyon area, including Navajo, Hopi, Ancestral Puebloan, Southern Paiute and Zuni.

1540: An exploratory party from Mexico, led by Capt. García López de Cárdenas, finds the Grand Canyon while searching for North America’s mythical Seven Cities of Gold.

1869: An expedition led by Maj. John Wesley Powell makes the first successful boat trip through the canyon.

1880s: Pioneers from the eastern U.S. begin displacing Hualapai and Havasupai residents as they build trails, roads and stage lines to woo prospectors and early tourists.

1887: First mule rides for tourists.

1901: The first Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe passenger train reaches the canyon’s South Rim from Williams, Ariz.

1903: Ralph Cameron, an entrepreneur who helped construct the Bright Angel Trail, starts charging a $1 toll to use the trail. This will go on for about 25 years before he is shouldered aside by the National Park Service.

1904: With Cameron as their landlord, brothers Ellsworth and Emery Kolb expand their photography studio from a tent cabin to a building by the Bright Angel trailhead. Their still and motion-picture images of mule-riding tourists and the rushing river help popularize the location.

1905: The Santa Fe Railway and Fred Harvey Co. open a grand hotel, El Tovar, designed by Charles Whittlesey. Harvey has Mary Colter design Hopi House. Her Lookout Studio, Hermits Rest, Phantom Ranch, Desert View Watchtower and Bright Angel Lodge follow.

1914: National Geographic magazine’s August issue includes 85 pages on the Kolb brothers and the canyon. (About this time, Ellsworth Kolb moves to Los Angeles, leaving his brother to steer the business for more than 70 years.)

1919: The canyon is named a national park. It draws 44,173 visitors in its first year.

1928: The Grand Canyon Lodge is built on the north rim of the canyon, burns down in 1932, is rebuilt in 1937.

1933-1942: Civilian Conservation Corps workers improve the Bright Angel Trail and several others, build stone walls along the village section of the South Rim, and run a telephone line between the South and North rims.

1956: On June 30, a United Airlines DC-7 and a TWA Constellation both dip into Grand Canyon airspace to give passengers a peek. The planes collide over the canyon, killing 128 people. President Eisenhower moves to strengthen air traffic regulation nationwide.

1976: Emery Kolb dies. The National Park Service acquires the five-story, 23-room Kolb Brothers Studio, which later becomes an exhibition space and gift shop for the Grand Canyon Assn.

2015: The Grand Canyon gets about 5 million visitors yearly. Rooms at El Tovar rent for $197 and up.

SOURCES

National Park Service, https://www.lat.ms/1Ph11NN, https://www.lat.ms/1aEiG2l

Xanterra Parks & Resorts, https://www.lat.ms/1NRP5hV, https://www.lat.ms/1a2nZr0;

Arizona State University, https://www.lat.ms/1y1xdiz

***

Grand Canyon mule trek: A ‘hard ride,’ but John Berry smooths it out

On a chilly morning near the Grand Canyon’s busy Bright Angel trailhead, a man with muddy boots, cowboy hat, bulging cheek and drooping mustache fixed his gaze on a handful of nervously smiling tourists.

“Your legs are going to be numb after the next two hours,” said John Berry, 47, livery manager for park concessionaire Xanterra.

The tourists nodded, eyeing the mules behind him. They had signed up for the ride to Phantom Ranch. Every day as many as 10 riders join guides on a journey down 10 miles of narrow trail to the canyon floor, about 4,400 feet below. Usually, the group sleeps at the ranch and ascends the next day on South Kaibab Trail.

The ride down is one of the Grand Canyon’s greatest rituals, dating to 1887, and these trips book up to 13 months in advance. (The cost is about $400 to $515 per rider, depending on the size of the group.) But the enterprise depends on riders trusting their lives to a mule. And on this morning, one rider was having second thoughts.

She was about 11, sniffling, trembling, terrified. Her father, mother and sister whispered to her, then finally brought her to Berry, who sees this about once a month.

“It’s not worth having somebody go if they’re scared. And she looks pretty scared,” he said gently, addressing the family. “There’s nothing to be ashamed of. I’ve seen adults get scared. … We do have a three-hour ride up here on top. That might be a good one for her.”

After brief consultation, the family withdrew and got a refund. The rest of the group saddled up, got final pointers from the guides who would be riding with them, then clip-clopped down the Bright Angel Trail. Somewhere at the bottom of the canyon, another group would be heading up.

“This is the biggest mule operation in the United States,” Berry said. “Heck, we could be the biggest in the world.”

But it has been bigger. In 1914 National Geographic estimated the South Rim’s tourist mule traffic at 7,000 riders per year. These days it’s half that or less. After decades of dispute between traditionalists and hikers who say the mules accelerate trail damage, the park has capped Xanterra’s mule traffic at 10 recreational riders per day below the South Rim. (There are, however, other rides offered atop the South Rim, and a North Rim concessionaire does canyon rides in summer.)

What prepares a man for this gig? Basically, said Berry, “I’ve been with mules all my life.” He was 13 when his family took over a string of pack stations in the Sierra Nevada near Bishop, Calif., in 1980, and before long he was taking mules into the high country.

Since then he has gone back and forth between the family business and the Grand Canyon. He has been in charge of the Grand Canyon operation since 2012. In his jeans pocket, you can see the outline of a telltale circle — a tin of chewing tobacco. On the wall of his office in the mule barn, you see a photo from a 1940 ride, and you hear a blacksmith trimming hoofs and hammering shoes.

The operation includes about 60 “dude mules” — animals with the surest hoofs, best manners and mildest tempers — along with 80 others that carry packs or work with trail maintenance crews. As boss, Berry manages the guides, matches riders with mules, keeps in touch with guides by walkie-talkie, makes contingency plans when the weather changes and rides the canyon about once a month.

He tries out every new mule himself. Last summer, when a 93-year-old customer showed up, Berry joined the ride as a precaution. (“He did just fine,” Berry reported.) And most workdays, he handles the pre-ride briefing, which contains life-or-death instructions peppered here and there with Wild West patter.

“We don’t sugarcoat it,” he said. “It’s a tough, hard ride. If you’re not used to riding, you’re going to be sore in places you didn’t even know you had.”

Along the way, you need to ignore vertigo, keep your mule from snacking and “motivate” your mule with a short leather whip if it decides to stop moving.

Berry and his guides are quick to tell people that in all these years of escorted mule rides into the canyon — involving an estimated 500,000 or more tourists — there hasn’t been a single fatality among saddled-up customers.

That remarkable statistic is confirmed by authors Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers in “Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon.” But it does depend on very specific language.

As “Over the Edge” notes, a saddled-up mule guide fell to his death (with his mule) in 1951. In 1998, a mule-ride customer dismounted for a lunch break, ventured near a steep cliff near Plateau Point and fell more than 400 feet to her death. And in its advice to hikers on Bright Angel, the park service notes several mishaps involving hikers and mules in recent years, resulting in “injuries to packers and the death of some mules.”

A tough, hard ride, indeed. Still, for most customers, these animals and this trail are the stuff of happy memories, not regrets.

“We show people one of the best things they can ever do,” Berry said. And he’ll keep doing it, he added, “until I retire or they fire me.”

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

READ MORE FROM THIS SERIES: Postcards from the West

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.