How San Diego’s, San Francisco’s rival 1915 expositions shaped them

- Share via

Reporting from San Diego — A hundred years ago, San Francisco had something to prove.

Its leaders wanted the world to know they had rebuilt since the earthquake and fires of 1906, and they wanted to woo the travelers and commerce that would be headed west through the just-completed Panama Canal. So they decided to throw a global party.

San Diego had something to prove too. It had about 40,000 residents — about a tenth of San Francisco’s population — but no cable cars, no Gold Rush glamour, no Mark Twain quotes. And a Mexican civil war was simmering just south in Tijuana. But San Diego wanted tourists and ship traffic. Even after President Taft and Congress threw their support behind San Francisco, San Diegans pressed ahead with plans for their own exposition.

The result: competing expos, assembled as World War I was beginning to tear Europe apart. This had all the makings of a civic disaster. Maybe two.

Yet both shows went on. In a state with fewer than 3.4 million people, they together tallied 22 million visitors. The city with the brighter lights and bigger crowds, however, isn’t the one that ended up with the larger architectural legacy.

Wonder by the bay

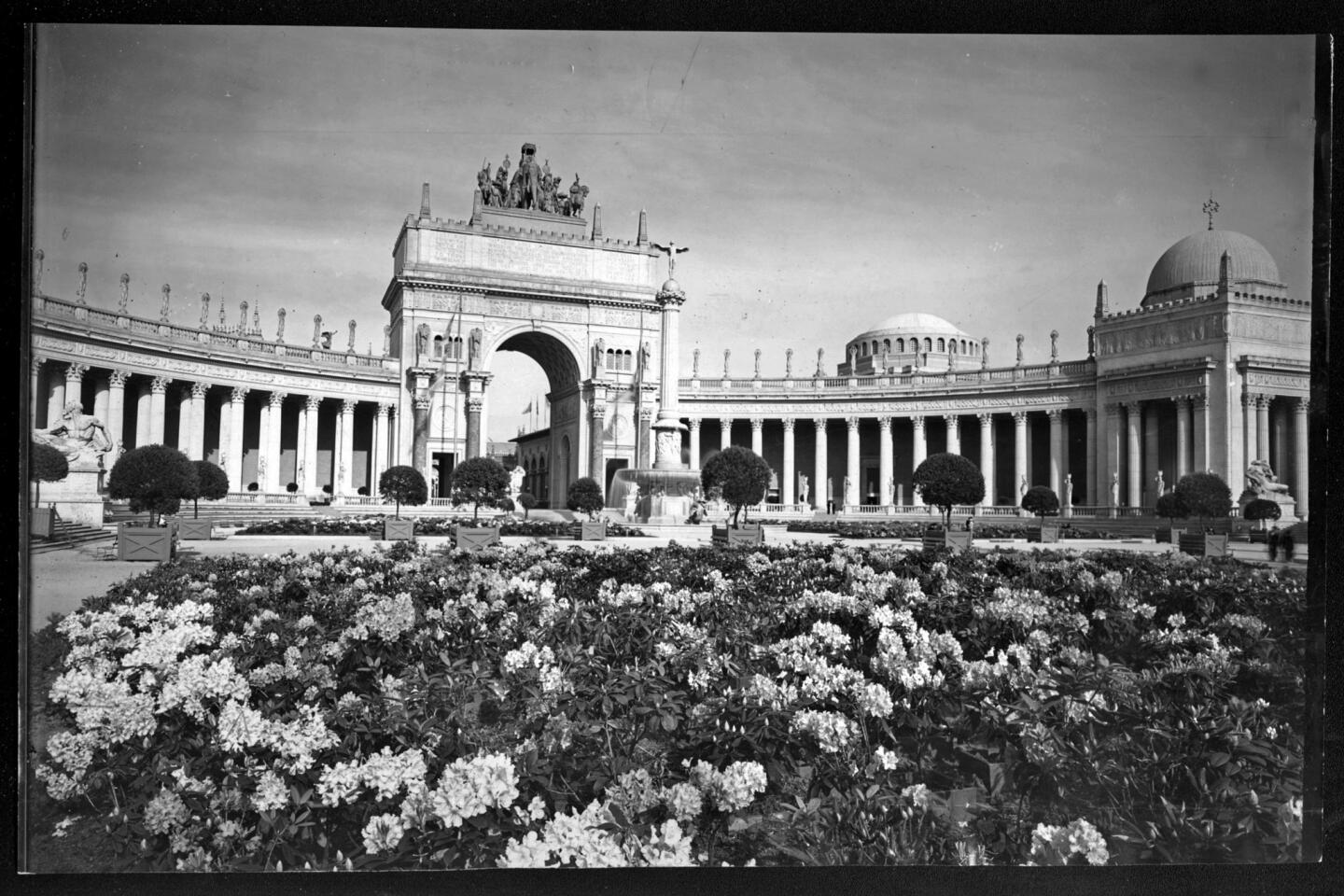

Once San Francisco had federal backing for its Panama-Pacific International Exposition — defeating not only San Diego but also a vigorous New Orleans bid — the local infighting began over where to put it. After flirting with the idea of Golden Gate Park, organizers decided to use 635 acres of lightly built marshland known as Harbor View, creating a bay-front playground just east of the Presidio and west of Van Ness Avenue. Nowadays, it’s known as the Marina District.

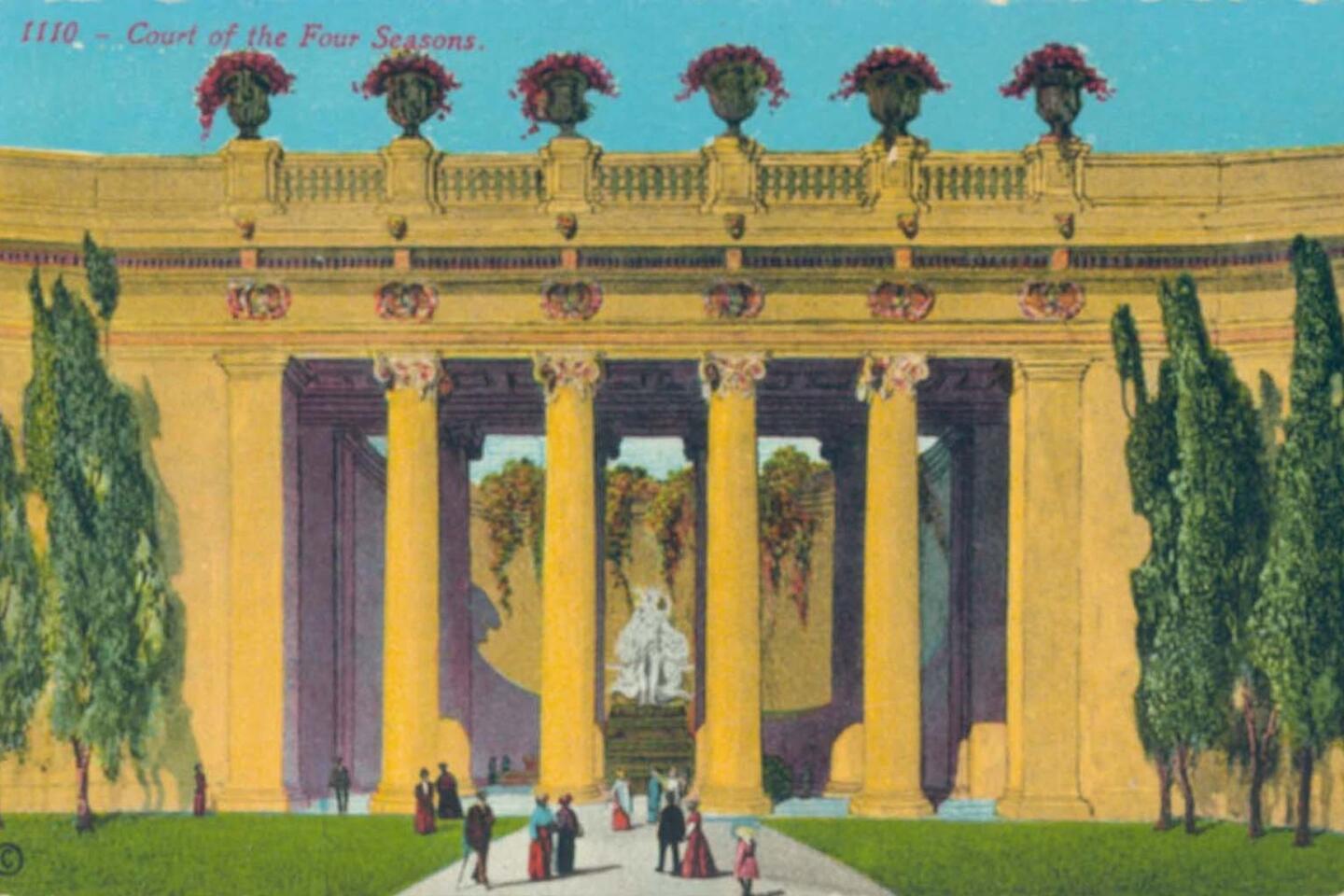

Except for a chunk of the Presidio and a bit of Ft. Mason, all this land was privately owned. The expo organizers leased it and set about building a temporary wonderland in grand Beaux-Arts style, with hundreds of statues and faux travertine by the ton.

The San Francisco expo ran Feb. 20 to Dec. 4, 1915. The expo’s central landmark was the Tower of Jewels, a 435-foot wonder encrusted with 102,000 cut-glass “jewels,” surrounded by hidden lights. (The “Jewel City” theme had been suggested in a newspaper’s naming contest by Virginia Stephens, a 12-year-old African American girl from Oakland.)

There was the Palace of Horticulture (with a glass dome larger than St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome), four 204-foot towers, a 638-room hotel (the Inside Inn), the Arch of the Rising Sun, a 7,000-pipe organ, a sprawling midway known as the Joy Zone, a 6-acre replica of the Grand Canyon, a 5-acre working replica of the Panama Canal, a pop-up factory making Levi’s jeans, a 15-foot-tall Underwood typewriter and a Ford assembly line turning out 18 Model Ts per day.

The Great Scintillator, a pier packed with 48 projector spotlights, stood near the fairgrounds for nine months, sending festive pastel-colored beams into the night sky and fog. To coordinate these displays, the expo hired a director of color, Jules Guerin, who envisioned “a gigantic Persian rug of soft melting tones” and told participating artists what hues they could and couldn’t use.

Despite many cancellations as World War I deepened in Europe, 21 nations sent representatives and materials for pavilions, as did 28 states and territories. (From Oregon: a Parthenon made of Douglas fir logs.) Neither Britain nor Germany put up pavilions, nor did Mexico.

But Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller and former President Theodore Roosevelt all came. Laura Ingalls Wilder, future author of the “Little House” books, marveled at a cow-milking machine. Ansel Adams, age 13, had a season pass and wandered the grounds daily, shooting photos with a Brownie box camera.

In all, nearly 19 million visitors turned out, a civic triumph for San Francisco by just about every measure. On the last day alone, 459,022 guests showed up.

And then it all but vanished.

Buildings were leveled, materials were salvaged and sold for scrap. Real estate reverted to its owners. And much was scattered among new owners. The plaster sculpture “End of the Trail,” by James Earle Fraser, a bowed depiction of a Native American on horseback that once stood in the expo’s Court of Palms, now graces the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

Among the significant structures, only one survived in its original location: the lagoon-adjacent rotunda and colonnades of the Palace of Fine Arts, which was bolstered by reconstruction in the 1960s. To see more of the 1915 expo in San Francisco, you must do some sleuthing — or visit during this year’s centennial exhibitions.

On the one hand, said Laura A. Ackley, author of “San Francisco’s Jewel City: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915,” the event made money, gilded the city’s reputation and “changed the standard for architectural illumination worldwide.” On the other, “it was so ephemeral. And the San Diego one lives on.”

San Diego’s vision

In the beginning, things didn’t look good for San Diego’s Panama-California Exposition. Organizers had far less money to spend, no federal blessing and plenty of discord.

Nationally acclaimed landscape architects John C. Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. signed on, then quit. So did a rising architectural star named Irving Gill.

Under the terms of a truce with San Francisco, San Diego had to leave the word “international” out of the name of its expo.

“At first, it was a rivalry,” said Iris Engstrand, a professor of history at the University of San Diego and curator of “San Diego Invites the World: The 1915 Expo” at the San Diego History Center. “But then they both realized they were both going to have a fair, and they’d better cooperate.”

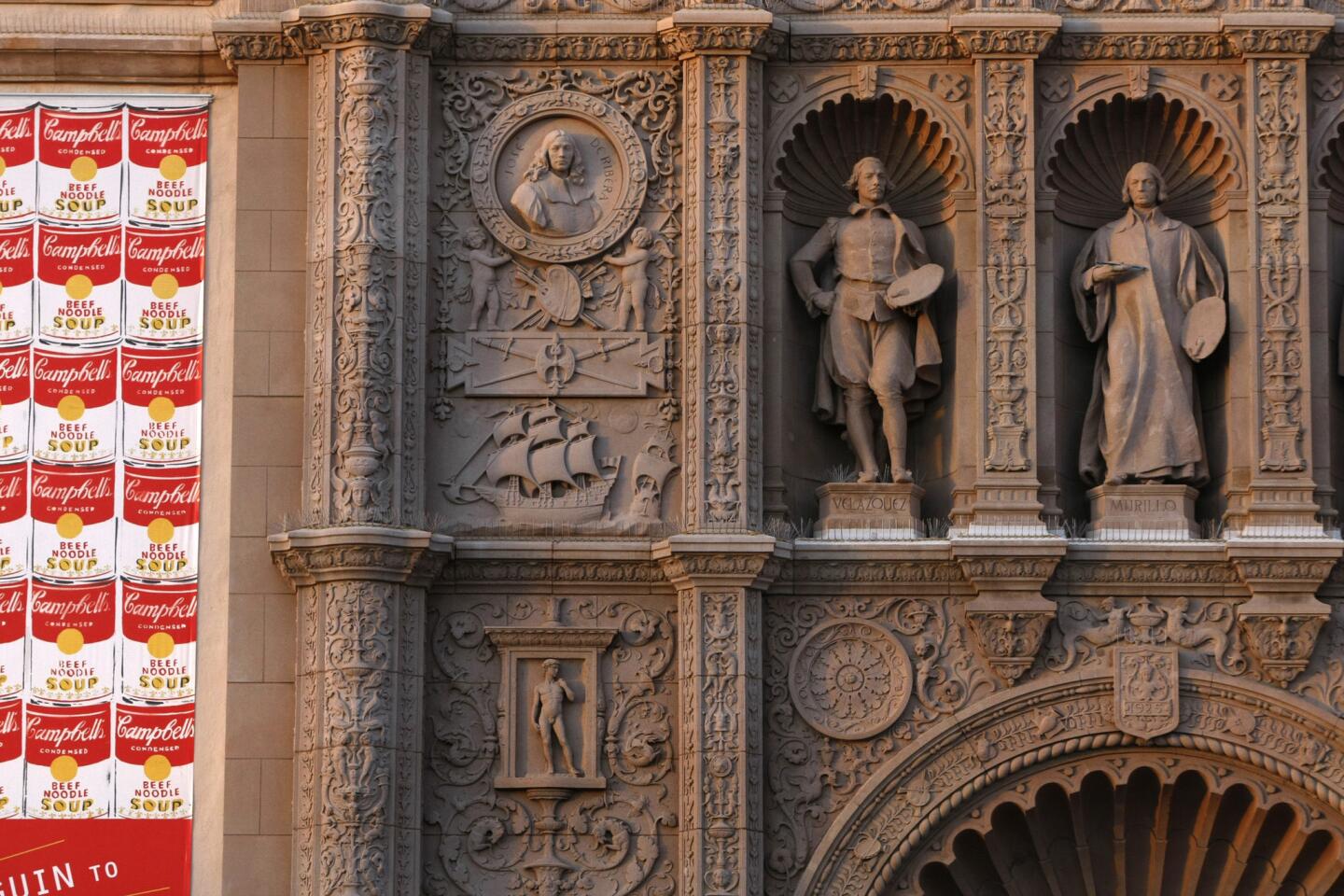

San Diego organizers staked out a 640-acre chunk of City Park, renamed it Balboa Park and chose a Spanish Colonial design theme, allowing a wide berth for Baroque Mexican flourishes, Moorish tiles and stark mission arches.

The centerpiece would be the California Building with a soaring tower and a tiled dome designed by New York architect Bertram Goodhue. It would be permanent, as would a new bridge, an organ pavilion and a vast wooden botanical building neighbored by a pond.

An Indian village, complete with a facsimile of New Mexico’s Taos Pueblo, filled several acres. Seven U.S. states put up buildings. Five buildings held exhibits from the counties of California.

Then there was the Isthmus, a half-mile-long midway where visitors found the Temple of Mirth, the Sultan’s Harem, a Hawaiian village, a Chinatown and a 250-foot-long model of the Panama Canal.

Building on success

Opening day was Jan. 1, 1915, about 50 days ahead of San Francisco’s. Two million people turned up in the first 12 months. Many San Francisco expo-goers made side trips to San Diego, including Roosevelt, Edison and Ford. After the San Francisco expo closed, San Diego’s fair kept going. In fact, it got a commercial second wind by bringing in foreign exhibitors and concessionaires who were happy to delay their return to a warring Europe.

In September of the expo’s second year, noted Richard Amero in “Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition,” Dr. Harry M. Wegeforth was driving nearby when he heard the roar of a lion on display along the Isthmus. He turned to his brother Paul and said, “Wouldn’t it be splendid if San Diego had a zoo?” Soon it did.

By the time San Diego’s expo closed on Jan. 1, 1917, attendance had reached about 3.8 million over two years, about a fifth of San Francisco’s total.

But San Diego’s key buildings had been built to last — and on public land. Moreover, as the decades passed, three temporary structures along the Prado promenade (now known as the Casa del Prado, the Casa de Balboa and the House of Charm) were saved and eventually rebuilt near the remodeled House of Hospitality.

Thanks to that fair, Engstrand said, “San Diego became a little more popular, although it has never achieved, even today, the status of San Francisco.”

Meanwhile, she added, Spanish Colonial architecture gained popularity in the West. In the course of their hosting chores, local leaders also forged ties that helped the city emerge as a Navy town.

Nowadays, the occasional San Diego purist may grumble about “the deranged phantasmagoria” of competing design ideas along the Prado (as author Amero did before his death in 2012), but Balboa ranks among the nation’s most admired urban cultural parks.

Its green spaces and 1915 legacy buildings have been joined by the Old Globe theater complex, the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center, the San Diego Air & Space Museum and about two dozen other organizations. The city estimates the park gets more than 14 million visitors per year.

San Diego’s expo centennial party has been marred by fumbles, including an aborted effort to reroute park traffic, and the failure of Balboa Park Celebration Inc., a nonprofit group that disbanded in disgrace after spending $2.8 million in public and private funds with little result. But there are events to mark the occasion (www.balboapark.org).

But if you take the long view in both cities, the expo is all good. San Francisco has brilliant memories, and San Diego has a cultural heart.

Palace of Fine Arts a ‘brilliant’ survivor of San Francisco’s expo

To find the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition’s legacy in San Francisco, proceed to the Palace of Fine Arts. Then start thinking like a detective.

Why the Palace of Fine Arts? Because that lagoon-adjacent building (3301 Lyon St.) is the only major 1915 expo structure still in its original location. The palace, a crowd favorite from the start, stood mostly on public property (which made it easier to save), and unlike most expo buildings, it was built with steel framing, not wood.

Another difference was its design — romantic — while other expo “palaces” followed Beaux-Arts style, relying on lighting to provide splashes of color.

“The more I actually studied the building,” said historian Laura A. Ackley, author of “San Francisco’s Jewel City: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915,” “the more I realized it’s an absolute tour de force of brilliant architecture.”

The palace is best known these days as a performing arts venue, but to mark the expo centennial, it will house a California Historical Society exhibition on the fair from Feb. 20, 2015 to Jan. 10, 2016. Another display in the palace, called “Innovation Hangar,” celebrates the spirit of innovation in the city. Also, San Francisco City Guides (sfcityguides.org) offers tours of the Palace of Fine Arts and of the Marina District, with much of the script devoted to the 1915 expo.

Now the detective work. Although most of the expo buildings were leveled, one replica was built, two grassy areas retain footprints of the fair, some artwork has been relocated, and there are exhibitions and books as well.

The Legion of Honor building (100 34th Ave., Lincoln Park), now part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is a double replica, twice removed. It was built in 1924 (three-quarter scale) as a facsimile of the 1915 expo’s French Pavilion, which was itself a facsimile of a Paris landmark dating to 1788. In fact, the original Palais de la Légion d’Honneur still stands in Paris on Rue de Lille in the 7th arrondissement.

The Marina Green, along Marina Boulevard, was known during the expo as the North Gardens. Back then, kids danced there, and a plane took off. These days, Ackley said, you look across the street to a row of 1920s homes. During the expo, “You’d be looking at a 65-foot-tall ivory-colored wall,” with intricate portals, complemented by flags and domes.

Crissy Field (along Old Mason Street between the Warming Hut and Crissy Field Marsh) was the western edge of the expo. In fact, work crews carted in sand, mud and silt to cover marsh and dunes for a dry, even surface for racing. The area included an 18,000-seat grandstand, an oval for car- and horse-racing and a running track and athletic field inside the oval. After the expo, it became a military airfield. Now it’s a grassy expanse that’s part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area. It has views of the Golden Gate Bridge, which didn’t go up until 1937.

In Golden Gate Park, near the Pioneer Log Cabin, stands the bronze statue “Pioneer Mother” by Charles Grafly. The artist produced it for the expo, and it was also part of the Golden Gate International Exposition (on the city’s Treasure Island) in 1939 and 1940. The sculpture has been in its current location since 1940.

The 1915 expo’s Court of Ages included eight massive murals on canvas — each 12 by 27 feet, depicting earth, air, fire and water — by painter Frank Brangwyn. In 1932, they were mounted on the walls of the War Memorial performing arts center’s Herbst Theater, and there they remain. The theater is closed for renovation, with the murals covered by plywood until a reopening in the fall.

The California Historical Society (678 Mission St.) will stage an exhibition on the expo from Feb. 22 to Dec. 6, “City Rising: San Francisco and the 1915 World’s Fair.”

The society is also part of a show at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, that displays 250 artworks from the 11,000 that were at the original expo, including some murals on canvas that haven’t been seen for years. The show runs Oct. 17, 2015 to Jan. 10, 2016.

For more on expo centennial events: www.ppie100.org.

To read and see more about the city in 1915: “San Francisco’s Jewel City: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915,” by Laura A. Ackley, and “Panorama: Tales From San Francisco’s 1915 Pan-Pacific International Exposition,” by Lee Bruno.

Reminders of Panama-California Exposition in San Diego’s Balboa Park

If you’d visited San Diego’s Balboa Park in the last 79 years to climb the handsome California Tower and look for reminders of 1915 — well, never mind. You couldn’t.

Although the tower is the park’s most widely visible structure — and its most obvious artifact from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition — its interior was closed to the public in the 1930s for reasons that are no longer clear. But now, as San Diego celebrates the expo’s centennial, the 200-foot-high tower is open again (to paying customers).

And even if you don’t sign up for the climb, you’ll see reminders of 1915 throughout the park’s core area.

Some highlights:

The California Building (which includes the tower) was the centerpiece of the 1915 expo, and its exterior has become emblematic of the city. Its interior is home to the Museum of Man (special exhibitions in 2015: monsters, beer and instruments of torture). The building features a colorful tiled dome, an elaborately ornamented façade and St. Francis Chapel, a nondenominational chapel that’s mostly used for weddings. As for the tower, daily 40-minute tours (weather permitting) started Jan. 1. Museum admission is $12.50 for adults, plus $10 for the tower tour. Info: californiatower.org.

The Botanical Building is a domed indoor-outdoor temple of redwood lath, fronted and reflected by a stately lily pond. The gardens inside feature cycads, ferns, orchids, palms and scores of other tropical plants. It’s free, but it’s closed Thursdays and holidays. (Among its neighbors: the San Diego Museum of Art, which looks like an expo building but isn’t; and the Timken Museum, which looks like a Modernist interloper from 1965 and is.)

The buildings now known as the Casa de Balboa, the Casa del Prado and the House of Charm went up along the Prado promenade in 1915 as temporary structures, mostly of wood and plaster. They were supposed to be leveled soon after the fair closed. But people kept finding reasons to keep them (including another expo in 1935). Since 1967, a group called the Committee of One Hundred has raised funds and support for their reconstruction. Now, with the House of Hospitality, they house dozens of cultural enterprises, including the Museum of Photographic Arts; a model railroad museum; youth performing arts organizations; the Mingei International Museum, which focuses on folk art; a visitor center; and the park’s premier restaurant, the Prado, whose cuisine might be described as “global eclectic.”

The San Diego History Center (in the Casa de Balboa) has organized two exhibitions: “San Diego Invites the World: The 1915 Expo,” to run Jan. 31, 2015 to March 31, 2016; and “Masterworks: Art of the Exposition Era,” to run Jan. 16, 2015 to Jan. 3, 2016. The center is also screening a 30-minute documentary, “Balboa Park: The Jewel of San Diego,” usually at 11 a.m. and 1 and 3 p.m. daily. Call (619) 232-6203 to be sure.

The Spreckels Organ Pavilion includes the Spreckels Organ, one of the world’s largest outdoor organs, with 4,530 pipes. At 2 p.m. every Sunday, there’s a free hourlong organ concert. Just about any time, the pavilion’s seats give you a chance to sit and relax.

The San Diego Zoo, now a 100-acre landmark (zoo.sandiegozoo.org) with a sibling San Diego Zoo Safari Park near the northern end of San Diego County, was conceived during the second year of that first expo. Its first animals, including a bear named Caesar, are descended from a group that was displayed along the San Diego expo’s Isthmus midway in 1916.

Cabrillo Bridge, designed as the expo’s grand entrance, is a concrete span of seven arches over Cabrillo Canyon and California 163. It was closed to cars for seismic upgrades and other repairs in early 2014, but is now open to pedestrians, cyclists and cars approaching from the west on Laurel Street.

For more about centennial events: www.balboapark.org.

To read more: “Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition,” by Richard Amero.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.