Postcards From the West: At Crater Lake, Ore., sky and water become one, bathed in blue

Crater Lake, a caldera nearly 2,000 feet deep and 4 1/2 to 6 miles across, is a mirror where a mountaintop should be.

- Share via

CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK, Ore. — The California border was just behind us, and Times photographer Mark Boster and I were roaring up a rain-soaked Oregon highway past fog-shrouded forests and green-stubbled boulders.

About an hour outside Ashland, Ore., the road began to climb. Pretty soon we were 7,000 feet above sea level and there was snow. It seemed as though we would run out of mountain and launch straight into the leaden heavens.

But instead, a great circle of what seemed to be sky burst into view below us, its surface rippling gently.

Crater Lake, a caldera nearly 2,000 feet deep and four and a half to six miles across, is a mirror where a mountaintop should be. The Crater Lake Lodge, its sidekick for a century, is a fortified folly on a perch better suited to snowdrifts and hemlock forest.

READ MORE FROM THIS SERIES: Postcards from the West

When you reach the rim, you can’t help but think of those brave or foolish souls who opened the first lodge in the summer of 1915: a four-story hotel on the edge of a dormant volcano, at the end of a rugged road, on terrain that gets 40-plus feet of snow a year. Only an epic view could sell such a project, and that’s what Crater Lake has.

We parked the car, tossed our gear into our rooms at the lodge and started prowling the caldera’s edge under intermittent rain.

Then it let up. The sky’s grays gave way to scattered blues. The view of the water, 2,000 feet below, snapped into bold-hued focus as if somebody had thrown a light switch.

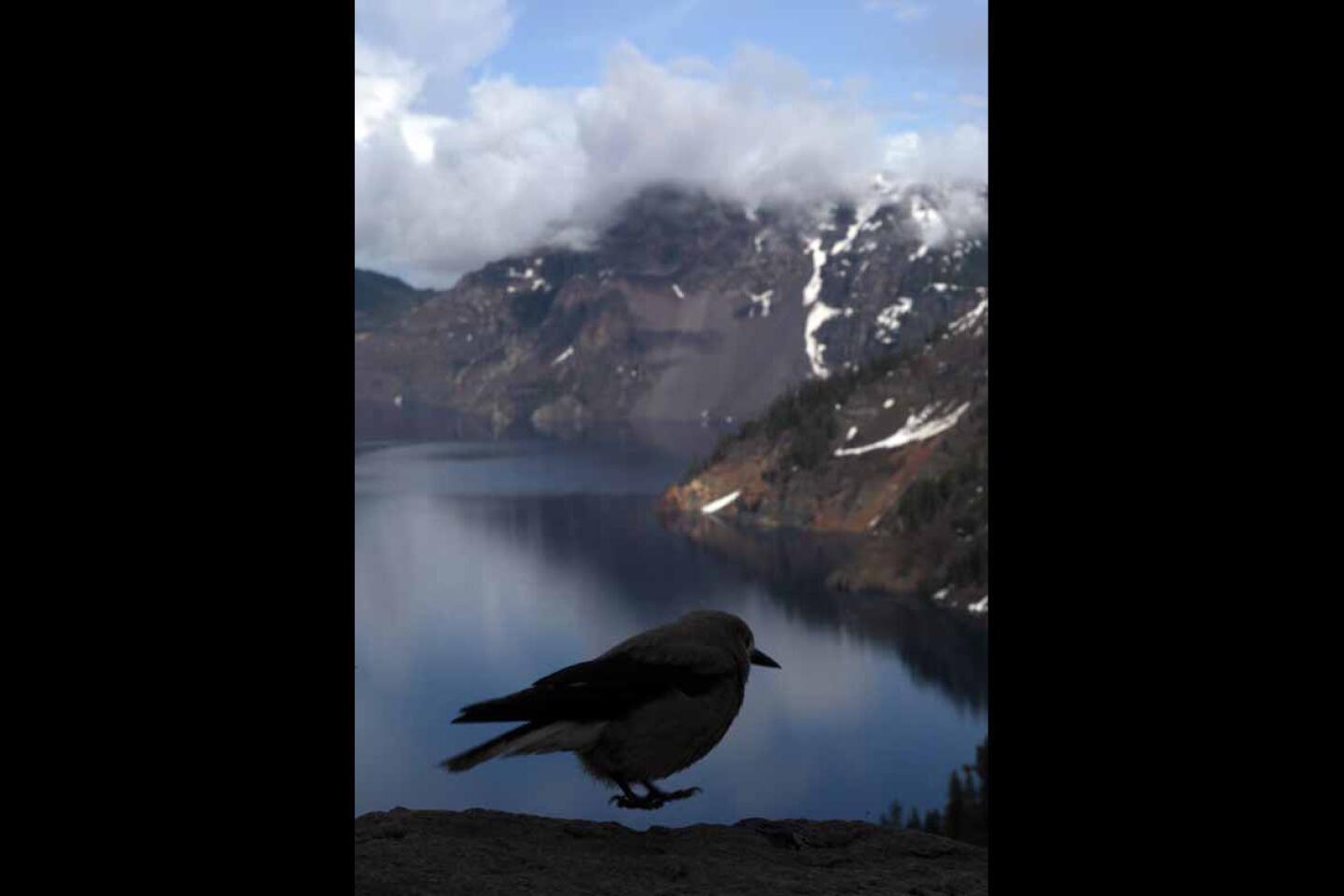

I had stood on the rim twice before, and it was just as jolting on this third visit in late May. Dew clung to the needles of the whitebark pines. Fearless birds with sharp little beaks swooped to pry seeds from the pine cones. (Clark’s nutcrackers, I later learned.) On the far side of the lake, which covers about 20 square miles, a new set of storm clouds massed and smudged the sky with rain.

Klamath tribal myth says the lake is the result of a battle over a woman between a god of the heavens (Skell) and a god of the underworld (Llao). When Llao lost, the volcano blew and the lake was created. In some versions, Wizard Island is what remains of Llao’s severed head.

The National Park Service version of the story is that a 12,000-foot volcano blew its top 7,700 years ago, leaving a 4,000-foot-deep caldera that happened to be symmetrical and watertight. As snow and rain fell, a lake began to form. Then, perhaps 400 years after the initial eruption, a smaller, younger cinder cone volcano, now known as Wizard Island, sprouted within the caldera.

We spent two days roaming the area: a damp dawn at Discovery Point, windy dusk at Watchman Overlook and a great hour at Rogue River Gorge, outside the park boundary. Between forays, we’d fall into the armchairs at the woodsy lodge, near one of the massive stone fireplaces. And I’d imagine how shoddy it used to be.

It took six years to build the first Crater Lake Lodge, which wasn’t quite enough time to do it right. When NPS Director Stephen Mather visited in 1919, he was scandalized by its poor quality. Alfred Parkhurst, the builder and original concessionaire, was soon shooed away.

Through the years, a parade of concessionaires followed amid complaints about structural strain, deferred maintenance, inadequate fire escapes and other issues. Even after the park service took ownership in 1967, troubles continued, including a sewage spill that contaminated the lodge water supply in 1975. Yet Oregonians grew to love the place.

Through much of the 1980s, park service leaders wondered aloud about leveling the lodge while preservationists rallied to protect it. In 1989 engineers declared it unsafe for habitation. By the time it reopened in 1995, the lodge was a new building with a familiar skin.

That’s when I visited for the first time, just a few weeks after the reopening. The view was intoxicating, but the service was a disaster. Somebody had quit, and the director of marketing had been pressed into service as maitre d’.

By April 2004, my second visit, veteran park concessionaire Xanterra had taken over the lodge, but it was still closed for the winter. I had come to write a column about its winter keeper, who basically had the Jack Nicholson job in “The Shining.” He proved to be about as menacing as Dale Carnegie, but I did get to see what winter does to the rim. The lodge’s first two floors were buried in snow, and walking its halls was like pacing in a submarine.

On this third trip, I had plenty of company and the front desk seemed to smoothly handle the daily tide of visitors. But the lodge’s cooks and servers kept surprising us by forgetting to bring a dish, substituting ingredients without warning or being grumpy. When dinner entrees hover around $30, that’s not a recipe for success.

The outdoors, however, has never let me down. The lake isn’t perfectly round or perfectly pure: There’s at least one crashed helicopter in it, along with two non-native fish species. But it meets the sky so well.

Before I said goodbye to Crater Lake this time, we did get a few more glimpses of the bright blue hues that astound tourists in July, August and September. And I got to see some newbies take in the scene.

“I’ve never even made a snowball before. I wasn’t expecting the snow and all the trees. That’s made it a thousand times better,” said Amanda McGrather, 24, visiting from Melbourne, Australia. Then she launched her first snowball into the face of her friend Ryan Jones, 22, of Jacksonville, Ore.

Rangers say most visitors at the park stay several hours, perhaps a night, but rarely longer, because there’s just one marquee attraction and because you can’t camp within sight of the lake.

I get that. But it’s too bad, because the longer you look at the lake, the more mesmerizing it gets. The green shallows at the edges of Wizard Island. The wind on the water. The shadows creeping down the slopes.

If current trends continue, I’ll be back in 2024 or so. And I might bring a sack lunch. But I’m not sure I can wait that long.

::

Crater Lake timeline

7,700 years ago

At the southern end of a volcanic range in the Pacific Northwest, a 12,000-foot volcanic mountain blows its top, showering lava and ash on the region. In the blank space where the mountain used to be, a deep caldera begins to fills with rain and snowmelt. The exploded mountain will later be named Mazama. The mountain range will be called the Cascades.

1853

While looking for a lost gold mine, prospectors John Wesley Hillman, Henry Klippel and Isaac Skeeters stumble upon the lake. They may be the first non-natives to see it, but because it holds no obvious mineral wealth, it is largely forgotten.

1869

Though others call the place Lake Majesty, Oregon newspaper editor Jim Sutton renames it Crater Lake, and it sticks.

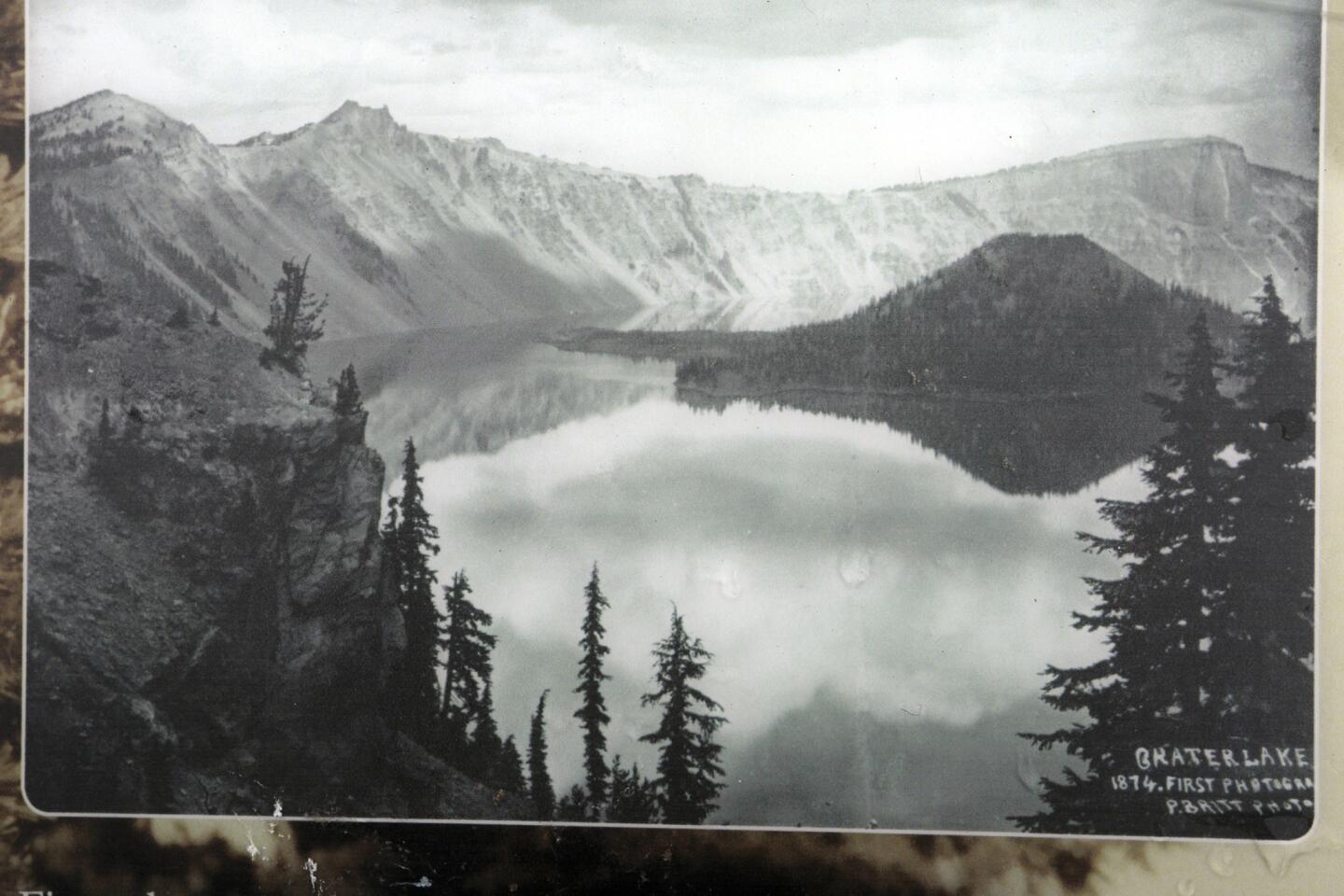

1874

The first known photograph of Crater Lake is taken by Peter Britt, a portrait photographer. The lake’s reputation begins to grow as the image is reproduced in magazines.

1886

Capt. Clarence Dutton leads a U.S. Geological Survey team to the lake. Its three boats include the 26-foot-long Cleetwood (which had to be lowered 2,000 feet from the caldera rim). Using weighted piano wire to measure depth at 168 different points, the team finds a maximum depth of about 2,000 feet. (Some sources say 1,996 feet, some say 2,008 feet.)

1888

The first fish are introduced into the lake. For the next 53 years, it will be regularly stocked with salmon and rainbow trout. (The Kokanee salmon and rainbow trout have endured and fishing is allowed; artificial bait only.)

1902

Crater Lake is named a national park, capping a 17-year campaign by local advocate William Gladstone Steel.

1913

Steel becomes the park’s second superintendent after a power struggle. The first superintendent, W.F. Arant, is forcibly removed by U.S. Marshals.

June 1915

Crater Lake Lodge opens. Portland-based developer Alfred Parkhurst claims that its steep roof has been designed to withstand heavy snow. As decades advance, winter conditions put the building under severe stress.

1918

Rim Drive is completed, allowing full circuits around the lake in summer.

1949

The lake’s surface freezes completely. (That hasn’t happened since, though 95% of the surface froze in 1985.)

1959

Using a sonar measurement, researchers calculate a new depth for Crater Lake: 1,932 feet.

1967

National Park Service acquires the Crater Lake Lodge, which needs a lot of work.

1980s

The NPS considers razing the lodge but backs down after protests, then closes the lodge in 1989 after structural engineers warn of a possible collapse.

May 1995

Crater Lake Lodge reopens, largely rebuilt and with its load-bearing capacity enhanced. In its new configuration, designed to deliver the feel of the 1920s, it has 71 rooms, all with private baths, none with TV or phones.

September 1995

A helicopter crashes into the lake, killing the pilot and his passenger. Along with the remains of the dead, most of the helicopter is left about 1,500 feet below the surface.

2014

The park marks its busiest year since at least 1979, tallying 535,508 visitors, most of them between June 1 and Sept. 30.

2015

The park begins a three-year project to upgrade Rim Drive and improve parking, making more room for bicyclists and larger vehicles.

SOURCES: National Park Service, www.nps.gov/crla; Crater Lake Institute, www.craterlakeinstitute.com; Oregon State University, www.lat.ms/1HTIq7C; “Crater Lake: The Story Behind the Scenery,” by Ronald G. Warfield, Lee Juillerat and Larry Smith, KC Publications.

MORE:

Ashland, Ore., is a Shakespeare-steeped literary retreat

A Crater Lake story: The Welches, 85 years young, relive their 1953 honeymoon

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.