MLB 1994 strike anniversary: Montreal Expos’ greatest season vanished overnight

- Share via

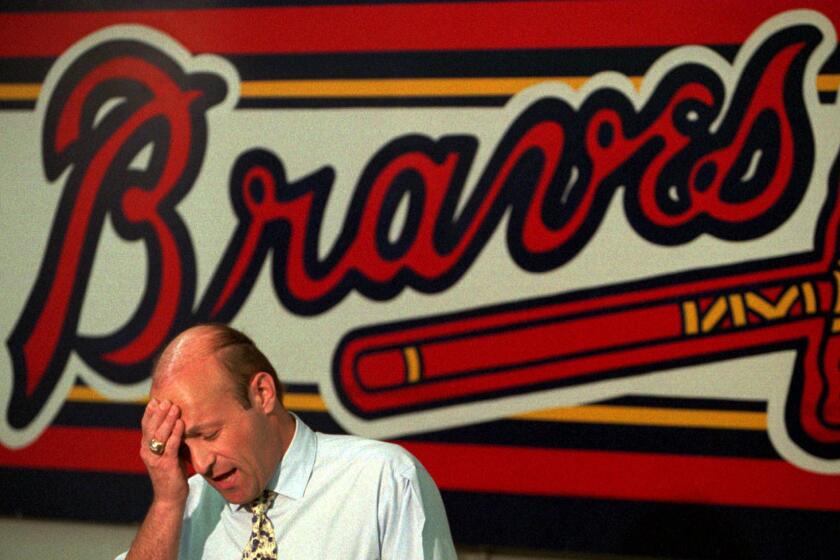

It was a feel-good story with no ending, a 4½-month joy ride with no destination. Baseball’s last work stoppage robbed the Montreal Expos of their best chance of winning a World Series in 1994, and the what-ifs and what-might-have-beens haunt Kevin Malone to this day.

“When I think about it, I can really feel that twinge in my stomach, that emptiness, that kind of sick feeling,” Malone said as he recalled the 1994 season, his first as Montreal’s general manager.

“It’s obviously not as intense as it was 25 years ago, but it’s still there. It’s almost like a scar that won’t go away, and by touching it, I can remember certain things about the season.”

The Expos, despite a $19-million payroll that ranked 27th out of 28 teams, had a 74-40 record — the best mark in baseball — and a six-game lead over Atlanta in the National League East when players walked off the job Aug. 12, 1994.

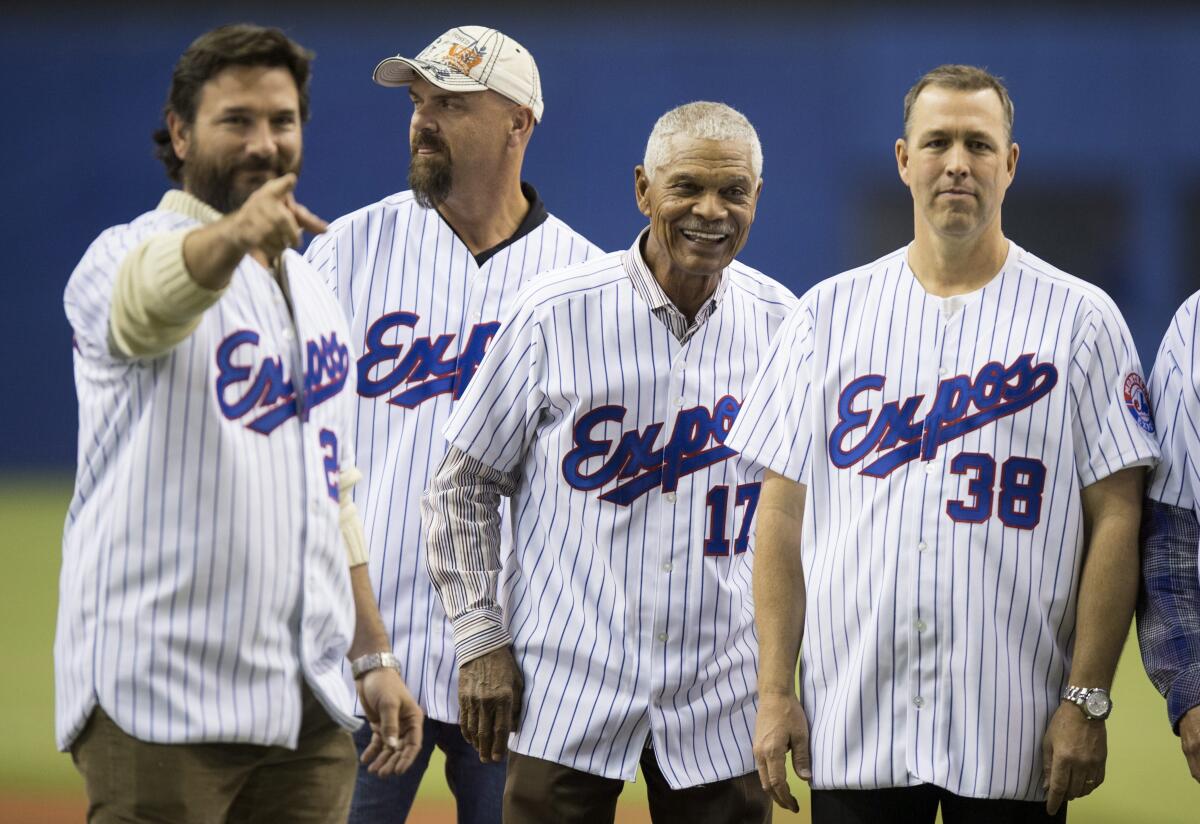

Montreal won 20 of its last 23 games before the strike. A dynamic team composed mostly of stars in their prime and promising youngsters, the Felipe Alou-managed Expos seemed poised not only for a deep October run in 1994, but also for a lengthy run as pennant contenders.

25th anniversary of baseball strike

A look back at the 1994 major league strike.

A balanced lineup featured power and speed, with Marquis Grissom (.288, 96 runs, 36 stolen bases) setting the table for Moises Alou (.339, .989 on-base-plus-slugging percentage, 22 homers, 78 RBIs), Larry Walker (.322, .981 OPS, 19 homers, 44 doubles, 86 RBIs) and Wil Cordero (.294, .853 OPS, 15 homers, 30 doubles, 63 RBIs).

A stout rotation was led by veteran right-hander Ken Hill (16-5, 3.32 ERA), 22-year-old right-hander and budding Hall of Famer Pedro Martinez (11-5, 3.42 ERA) and veteran left-hander Jeff Fassero (8-6, 2.99 ERA).

A lock-down bullpen featured closer John Wetteland (2.83 ERA, 25 saves) and setup men Mel Rojas and Jeff Shaw, with Gil Heredia and Tim Scott providing solid middle relief.

“We could hit home runs and manufacture runs, we were athletic, we played good defense and had good pitching,” Malone said. “We had so many different weapons and could win in so many different ways.

“We got on a roll, won a bunch of games and felt we were unbeatable at times. And we played with a chip on our shoulders because most of the guys weren’t highly paid. They were younger, still proving themselves, and we were a small-market team in Canada. It created an us-against-the-world attitude.”

The Expos played their final game that season Aug. 11 at Pittsburgh, a 4-0 loss. Malone addressed the team that day in Three Rivers Stadium.

“I let them know it looked like [players] were going on strike, and the look on guys’ faces, it was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” Malone said. “It felt like I got punched in the gut. But honestly, I felt like they’d get it settled, that the strike would last for a week or so.”

The strike dragged on, and on Sept. 14, commissioner Bud Selig canceled the rest of the season.

The following spring, Claude Brochu, former president and principal owner of the cash-strapped Expos, told Malone the team would not be able to add payroll for 1995. Over a two-day period in April, Malone conducted a fire sale.

Walker was not tendered a contract and signed a four-year, $22.5-million free-agent deal with Colorado, where he won the 1997 NL most valuable player award. Hill was traded to St. Louis, Wetteland to the New York Yankees and Grissom to Atlanta. The return: two big leaguers and five marginal prospects.

“We didn’t get good value back because teams knew we had to trade those guys,” Malone said. “They held us hostage.”

Malone estimated it would have cost about $24 million to retain Walker, Hill, Wetteland and Grissom.

“I said to Claude, ‘Let’s try to spend $12 million to keep two of them and try to keep this thing going,’” Malone said. “But the decision from ownership was no. We didn’t have the revenue. It was then that I realized this was the beginning of the end for the organization and for me in Montreal.”

The Expos were competitive for two months in 1995 but faded in June. They finished last in the NL East at 66-78, 24 games behind Atlanta. Malone resigned after the season and took a job as Baltimore’s assistant GM. He went on to be the Dodgers’ GM from 1998 to 2001.

Attendance in Olympic Stadium fell from an average of 24,543 per game in 1994 to 18,189 in 1995, and it continued to slide, dropping 7,935 in 2001, when the franchise was nearly contracted by Major League Baseball. After 2004, the Expos moved to Washington and became the Nationals.

Malone, now 62, lives in Las Vegas and is co-founder and president of the Tampa-based U.S. Institute Against Human Trafficking. But he still wonders what might have been.

Malone believes that had Montreal played out the 1994 season, the Expos would have experienced a renaissance like Seattle did in 1995, when the Mariners went on an exhilarating September and October run that resurrected the struggling franchise, fueled the push for a new stadium and saved baseball in the city.

“We were generating so much interest in 1994, corporate sponsorships and season-ticket sales were on the rise — maybe we could have gotten a new television deal and some new revenue streams that would have allowed us to keep two or three of those players and keep this thing going,” Malone said.

“I do believe the strike was the end of baseball in Montreal. I wish we could have finished what we started. I guess it wasn’t meant to be.”

On the 25th anniversary of the most notorious work stoppage in sports, The Times takes a look a the impact the 1994 Major League Baseball strike had on the game, its players and its fans.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.