MLB 1994 strike: Angels emerged stronger after walkout ended ho-hum season

- Share via

The 1994 strike marked a turning point of sorts for an Angels team that had been perpetually frustrated for more than a decade.

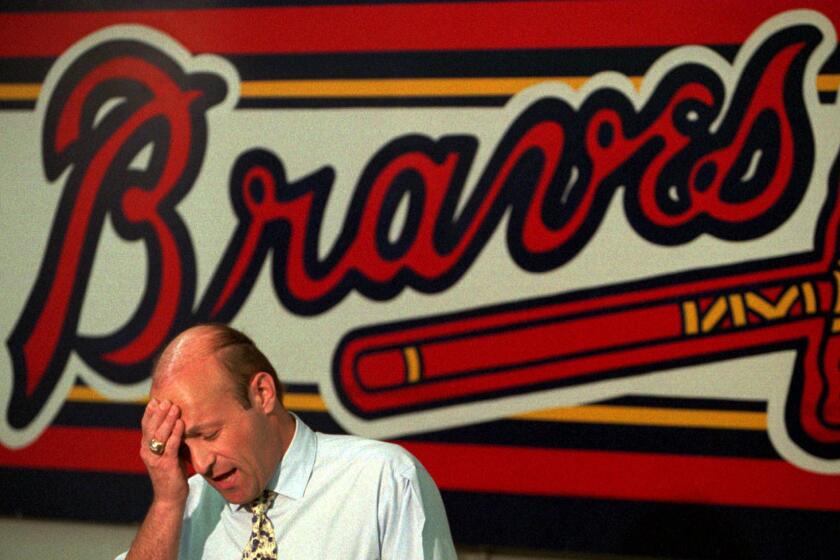

The Angels, and the rest of the American League West, had little at stake when the strike began. They were well under .500 and somehow still only 5 1/2 games out of a playoff spot. General manager Bill Bavasi even entertained trading for a closer.

“The only thing I can compare it to is the movie, ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’” Bavasi said. “Somebody should have put that division out of its misery.”

The strike accomplished that — although there was at least one under-the-radar casualty. Angels utilityman Rex Hudler failed to get a hit in his final at-bat before the strike and his batting average slipped under .300. He had not finished better than .282 during his previous eight major league campaigns.

“It was one of the most depressing outs I ever made,” Hudler said.

Even more distressing was the limbo the players had launched themselves into. They had known for weeks the disputes would come to a head. Instead of celebrating Gary DiSarcina’s walk-off hit in a 2-1 win over the Kansas City Royals on Aug. 10, the Angels laid out their bags after that Wednesday night game and stuffed them with belongings. They were supposed to travel to Detroit the next day and were uncertain they would return to Anaheim Stadium.

25th anniversary of baseball strike

A look back at the 1994 major league strike.

The morning of Aug. 11 the bags were loaded onto buses for the drive to the airport. The coaches and trainers took their seats. But no players showed up and the trip was canceled.

When baseball ground to a halt Aug. 12, leading to the cancellation of the season a few weeks later, the players hunkered down to fight.

Pitcher Mark Langston, who has been a radio analyst for the Angels since 2013, was the Angels’ union representative. He held hours-long conference calls with his teammates during the labor strike, reiterating to those whose conviction had begun to waver how important it was to stay united.

“We were trying to protect [ourselves] to the point to where we got to,” said Langston, who was 33 at the time. “There were many, many people well before us that laid it out for us. That was the theme you talked to the players about.

“You can’t go backward. You start going backward, that’s never going to reappear again. That will disappear forever.”

Said outfielder Tim Salmon, who’d been American League rookie of the year in 1993: “We weren’t complaining about what we had. We were trying to maintain it. We knew what a salary cap would do.”

The players eventually won, and the Angels, improbably, came back stronger.

In 1995 the strike ended, baseball resumed April 26, and the Angels flourished. Center fielder Jim Edmonds became an All-Star for the first time. Left fielder Garret Anderson and closer Troy Percival finished second and fourth, respectively, in rookie-of-the-year balloting. Salmon hit .330 and finished third in the race for the batting title.

Manager Marcel Lachemann and the coaches ruled with a firm touch. The Angels grew more disciplined. They were never more than three games out first place. They won 17 of 20 games after the All-Star break and built an 11-game lead in the division.

But the Angels spiraled when DiSarcina, the shortstop, suffered a thumb injury that sidelined him for seven weeks. The offense that had produced 6.2 runs per game was nearly silenced. All-Star left-hander Chuck Finley, who had given up more than three earned runs in only five of his first 21 starts, stumbled. The pitching staff had a 5.19 ERA in the final 56 games. It was one of baseball greatest collapses.

The Angels resurrected their postseason dreams by winning five of seven games to tie for the division lead and force a one-game playoff in Seattle. The Mariners won in a blowout, with Randy Johnson pitching a three-hitter and striking out 12 batters.

Underpinning those exponential strides was a savvy preseason move that shipped Chad Curtis to Detroit for veteran leadoff hitter Tony Phillips. Phillips provided the boost advance scout Matt Keough, who pushed Bavasi to make the trade, predicted he would.

“It was a mixture of youth coming into their own with some good vets around them,” Salmon said.

The Angels’ frustrations, of course, did not end for several more years. Strife at the top of the organization continued to trickle down to the field. They didn’t reach the postseason until 2002.

The Angels, still relying on Salmon, Percival and Anderson, won the World Series that year. The trio helped usher in an age of prosperity that could trace its beginnings back to baseball’s darkest moment.

The strike had pushed Angels executives to improve team culture. Their efforts finally bore fruit.

“A lot of that team was together for the World Series in 2002,” Bavasi said. “They kind of learned how to be men on that 1995 club.”

On the 25th anniversary of the most notorious work stoppage in sports, The Times takes a look a the impact the 1994 Major League Baseball strike had on the game, its players and its fans.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.