- Share via

A summer breeze flutters across the beach at Lower Trestles, cool to the skin, carrying the promise of rain from low, gray clouds that gather overhead, but the waves are pumping and Kolohe Andino is getting fidgety, eager to pull on a wetsuit and paddle out.

With a blue flannel shirt hanging loosely from his slender frame and a ball cap tugged down over disheveled, blond hair, Andino looks every bit the way he describes himself.

“I’m just a scruffy surf nerd,” he says.

It wasn’t so long ago that the San Clemente native was hanging around his place, watching television, when a commercial with gymnast Simone Biles came on and an odd notion crossed his mind: Wow, I’m kind of like her.

At first glance, no one would mistake the pro surfer for Biles, who is compact, powerfully muscular and a Black woman. But this summer Andino will be kind of like Biles because his sport is making its Olympic debut and, as a familiar name on the world tour, he will join the iconic gymnast on a U.S. squad headed for Tokyo.

Andino won’t be the only oddity on the American roster.

Just a half-hour north on the San Diego Freeway lives Nyjah Huston, a pro skateboarder with earrings in both ears and tattoos from his chin to his feet. Huston still gets chased away by police when he and his friends experiment with new tricks at the park or in front of a public building — it is hard to imagine Michael Phelps or Usain Bolt getting rousted by the cops during practice.

Laguna Beach’s Nyjah Huston brings a fierce commitment to training to a rebellious sport, making the skateboarder a star to watch in the Tokyo Olympics

In all, the inaugural U.S. surf and skateboard teams will include seven Californians, none of whom quite fit the traditional Olympic mold. They have been incorporated into the program for a reason.

Think of it as the Californication of the Games.

Subscribers get early access to this part of our Tokyo Olympics coverage

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our preview of the 2021 games. Thank you for your support.

These newcomers and their sports represent the latest example of a campaign by the International Olympic Committee to rejuvenate its aging brand and attract a new generation of fans, sports historian Bill Mallon says. Following the successful addition of Santa Monica-born beach volleyball, there appears to be an underlying theme.

“They try to pick up on what the youth are doing,” Mallon says. “And a lot of that comes from California.”

There are other connections between the Olympics and a state that has hosted them three times, four if you count the upcoming 2028 Los Angeles Games. Maybe, as Encinitas skater Bryce Wettstein suggests, “it’s just one of those things that’s so unreal and organic.”

::

You could make an argument that it all started with Tarzan.

As a professor and sports historian at Penn State, Mark Dyreson has tracked the infusion of California cool into the Olympics and contends that it traces to Johnny Weissmuller swimming for the U.S. at the 1924 and 1928 Summer Games.

The son of an immigrant miner, square-jawed and strong, Weissmuller was a superstar in his sport, setting 51 world records and winning five gold medals. Letting his dark hair grow long, he parlayed this success into Hollywood fame, playing the Ape Man in a dozen movies.

“Swimming was transnational but in some ways it was the first Californized sport,” Dyreson says. “Hollywood emerges as arguably the global media center and companies are already marketing the California zeitgeist, the beach attire and a pool in every backyard.

“This is a huge industry that can sell to the world,” he says.

The entertainment connection would prove just as crucial with surfing.

Though the sport originated in Polynesia, making its way to the mainland from Hawaii through the early 1900s, it was presented to the rest of the world through a specific lens. The 1959 movie “Gidget,” with Sandra Dee playing a teenage girl hanging around Malibu with her friends, created a sanitized, Southern California version of riding the waves.

“It popularized surfing around the world and turned it from a niche expression into something terribly mainstream,” says Jess Ponting, director of the Center for Surf Research at San Diego State.

As with swimming before, the line between sport and commerce had blurred, resulting in an image that could be peddled to the multitudes.

“That film spawned surf music and spawned kitschy spoof movies like ‘Beach Blanket Bingo,’” Ponting says. “It perpetuated surfing as a Southern California, hang around the beach and look beautiful kind of thing.”

At the time, the IOC already had a long history of adding new sports to its program, a routine that proved occasionally disastrous.

The swimming obstacle race was dropped immediately after its debut at the 1900 Paris Games and tug-of-war lasted only a little longer. Similar fates befell club swinging and an oxymoronic competition called solo synchronized swimming whose short life began at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

As the years passed and the IOC watched its base grow steadily older, tinkering with the program became more targeted. Olympic officials began looking for events based “mainly at how telegenic the sport is for television and how popular it is with young people,” Mallon says.

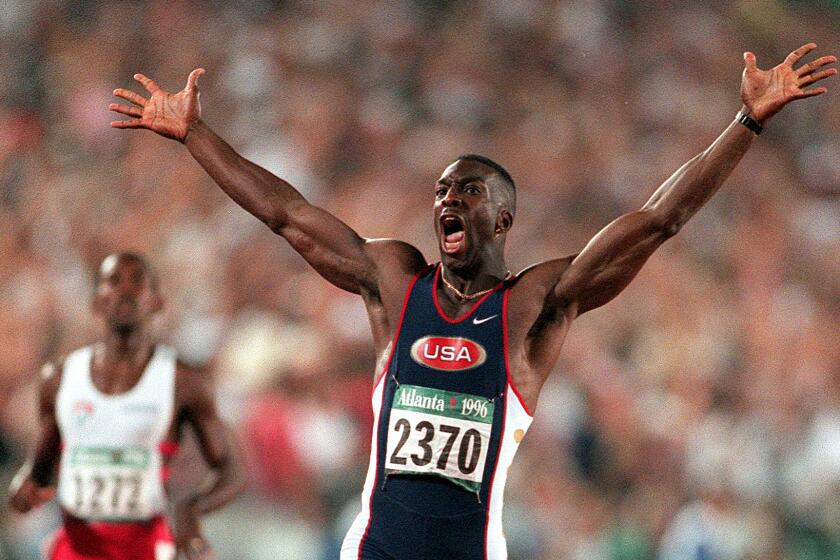

Beach volleyball, which in its two-player version dates to the 1920s in Santa Monica when beachgoers couldn’t wrangle enough bodies for two full teams, might have seemed a mere curiosity when it officially debuted at the 1996 Atlanta Games, but soon attracted a worldwide audience.

“If you go down to any beach in Southern California during the summertime, it’s wall-to-wall volleyball nets,” Ponting says. “That has translated into more participation, which feeds back into viewership and support for the Summer Olympics.”

As American colleges begin to cut some sports, the effects could be seen on future Olympic medal stands.

Snowboarding fell into a similar category at the Winter Games as the IOC continued to chase global appeal.

Surfing represented the logical next step. Media treatment of the sport had grown more sophisticated since the “Gidget” days and the numbers were appealing, with participation estimates ranging from 17 million to 35 million. Australia, South Africa, Brazil and — not coincidentally — Japan had developed surf cultures of their own.

Just as important, the sport had achieved crossover success, selling to consumers who lived hundreds if not thousands of miles from the nearest point break.

“You can buy the shirt or the Vans shoes and you can buy the sunglasses,” Dyreson says. “You can consume it at a distance and feel like you’re in sunny Southern California, hearing strains of the Beach Boys, even though you’re in Vladivostok.”

Skateboarding has similar reach and appears to be rebounding after a lull in popularity. The sport originated in the early 1950s with surfers looking to glide down Southern California streets on days when the ocean lay flat; like surfing, it eventually gained pop-culture traction with music and clothing styles.

Now, the marketing power of surfing and skateboarding cannot be underestimated. Among other new sports in Tokyo this summer, sport climbing does not deliver as much name recognition and karate does not have the sales punch.

With the California sports, Ponting says, “there is an undertone of freedom and, to some extent rebellion, but mostly freedom of expression. It’s hard to generate that aspirational lifestyle around pole vaulting.”

::

A crowd gathers at the water’s edge as Kelly Slater emerges dripping wet, stepping gingerly over the rocks, board tucked under one arm. Nearing 50, the 11-time world champion still can put on a show, catching wave after wave, screaming down the line and snapping cutbacks during an exhibition at a Lower Trestles contest. Everyone wants an autograph.

Though he missed making the U.S. Olympic squad, Slater has been named as an alternate and could replace John John Florence, recovering from a knee injury, at the last moment.

“We bring something that maybe a lot of sports don’t,” he says of surfing. “We’re a sport you do for life, from when you’re a little kid till you’re 90 years old.”

Slater also wonders if adding a little more California will force the Games to adapt. He laughs and says: “Hopefully it loosens them up a bit.”

In Tokyo, the surf competition will employ a format familiar to anyone who has watched pro contests on television, with small groups of athletes competing in heats, judges scoring them on every ride. While other sports must adhere to a strict timetable, every game and match planned down to the minute, surfers know that a higher power dictates when they can paddle out.

“The ocean can be flat,” Andino says. “You’ll just be watching a flat ocean and two dudes sitting there.”

The men’s and women’s events at Tsurigasaki beach will be given a wide window, with four days of competition taking place at some point over the course of eight days, depending on conditions.

Watching the horizon for swells, scrutinizing tide charts, the wind and the ocean floor makes surfers particularly attuned to nature. Perhaps this connection gives them a different perspective on life.

“We’re super-used to adapting and going with the flow,” says Caroline Marks, a member of the U.S. team and Florida native who relocated to Southern California five years ago for better waves. “That’s the beauty of the sport and I hope people will see that.”

The skating competition in Tokyo will focus on two of the sport’s main styles. Though vert contests might be best known to the general public, with skaters launching themselves airborne off massive wooden ramps, flipping and spinning through the air, it won’t be part of the program. Instead, there will be a park competition with smaller, concrete halfpipes like those found in public skate parks and a street event with rails and stairs.

The IOC knows the latter two iterations are far more accessible to kids around the world.

“Not everyone has a vert ramp to skate or a mini-ramp in their backyard,” says Neftali Williams, a USC post-doctoral scholar and Yale visiting fellow who studies skateboard culture. “Do [Olympic officials] want to change and have a younger demographic and be more relevant? There is a potential for that.”

Though skating fits into a strict timetable, it brings a different sort of attitude — all those tattooed arms, the blaring music and a rebelliousness — that doesn’t quite align with conventional notions of Citius, Altius, Fortius.

“What’s important, by having skaters and surfers there, it changes the notion of who is considered an athlete and what an athlete looks like,” Williams says. “When you talk about diversity, that’s what you encounter.”

Huston, the world’s top-ranked street skater, puts it this way: “I guess you can call it a sport but, in my eyes, it’s a lifestyle. It’s going out there and having fun with your friends.”

The 16-year-old Wettstein has given some thought as to how this might lend a different ambiance to the Games. She suspects that traditionalists will cringe at adding ollies, fakies and noseblunts to the realm of javelins, somersaults and single sculls, but she sees this change as “a beautiful thing.”

“Putting on a competition with a high platform,” she says of skateboarding, “you’re finally meshing the art and the sport together, which is completely enhancing.”

The Olympics might not have a choice, with experts insisting the IOC must evolve to bring new fans into the fold.

That means inviting the likes of Andino, Huston and Marks to a competition better known for athletes such as Biles, Phelps and Bolt. It means giving the Olympics a taste of something different.

Something looser and free-flowing. Something that doesn’t follow the old rules.

“A beach party vibe,” Ponting says. “It comes back to California cool.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.