- Share via

The story goes back a ways, back to the mid-1980s, when Michael Johnson was still in high school.

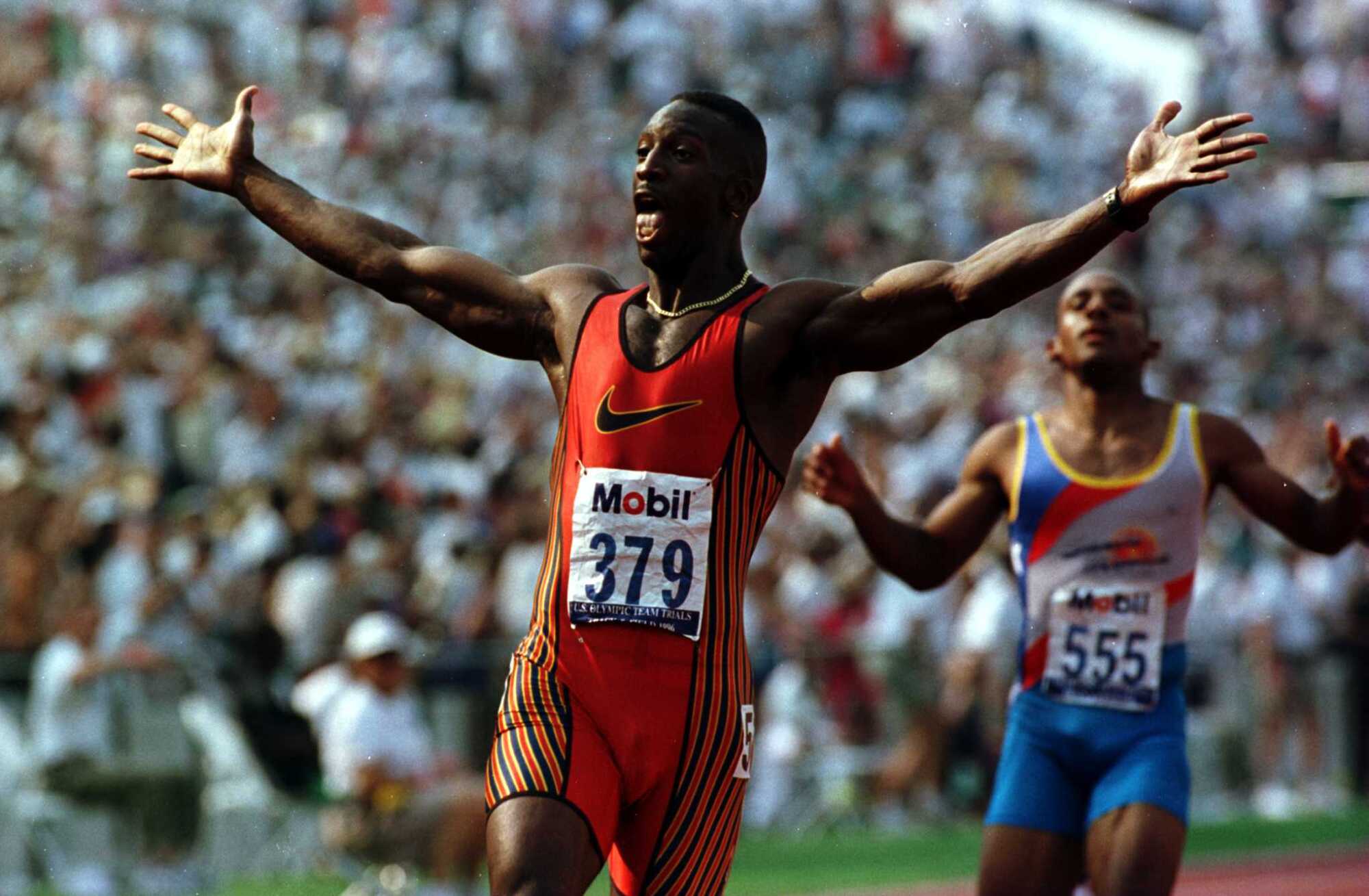

The famous sprinter was years away from winning gold medals at three consecutive Summer Olympics. He wasn’t yet known for those glittering golden spikes.

A nerdy kid, Johnson was running track at a small magnet school in Dallas. The team’s coach, Joel Ezar, who taught health class during the day, knew only a little about technique but could spot raw talent.

“No one was paying attention to me,” Johnson recalls, “until he started writing letters to all these colleges.”

Baylor University offered the unpolished athlete a chance to hone his skills with a coaching staff versed in speed and strength training.

“It was a critical moment for me,” says Johnson, who wonders whether he might otherwise have fallen through the cracks and never become an Olympian. “I made a huge leap when I got to college.”

The latest Virtual Medal Table from Gracenote shows the U.S. leading all nations with an estimated 43 golds and 114 overall medals at the Tokyo Olympics.

This story might sound quaint but it shows how college sports have served as a vast feeder system, helping the Americans dominate every Summer Games for the past 25 years and making them favorites to again win a lion’s share of medals at the Tokyo Olympics.

People need to know how it works, Johnson says. They need to understand because the U.S. winning streak could be history — no more piles of gold, silver and bronze — by the time the 2028 Los Angeles Games come around.

::

Countries such as China, Russia and Germany follow a different method, identifying a relatively small number of prospects at an early age and funneling them into specialized training academies.

The U.S. relies instead on its broad network of colleges to serve as a kind of minor leagues. Casting a wide net, this system has a history of identifying and developing talent such as sprinter Carl Lewis and volleyball great Misty May-Treanor. It has given late bloomers such as Johnson, with his awkward, upright style, a few more years to mature.

“College allowed me to grow up as a young man. I had dreams of being an Olympian but I needed to understand my goals.”

— Quincy Watts, a USC alumnus and a two-time gold medalist in sprints

As a result, the American team can choose from thousands of candidates to restock its roster every four years.

But that pipeline is now in danger of slowing to a trickle, in large part because of the COVID-19 pandemic and its financial impact, with scores of universities cutting costs by downsizing their athletic departments.

Football, a non-Olympic sport, and basketball, a prominent Olympic sport, but one that yields few medals, have been spared because they generate tens of millions through ticket sales and broadcast rights. The ax has fallen instead on such sports as the Summer Games trinity of track, swimming and gymnastics, which operate at a deficit. So far, hundreds of teams have been eliminated nationwide.

Prominent NCAA schools such as Iowa, Minnesota and Connecticut have made cuts, as have many smaller Division II and Division III campuses.

A few universities, including Brown and Clemson, have backed down in the face of public pressure. Stanford, which ranks with USC and UCLA in sending athletes to the Olympics, reinstated 11 teams it planned to drop. Still, officials see a worrisome trend.

“Eighty percent of our Summer Olympics teams come from college,” says Sarah Wilhelmi, a U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee executive. “When college programs are cut, there are dominoes related to those cuts.”

A smaller talent pool means fewer athletes to choose from, fewer chances to strike gold. If the trend continues, Americans could soon be knocked off their perch atop the medals table, the unofficial scorecard that fans watch so closely at every Games.

Painful memories will endure from Misty Hartung’s year fighting for Stanford athletes in their battle with university leaders who chose to turn their backs on them.

The U.S. squad headed for Tokyo won’t be affected — one forecast has the team winning 114 medals, comfortably ahead of all other countries. But officials worry about the 2024 Paris Games and Los Angeles beyond that. They have created a think tank, inviting dozens of university administrators, coaches and former athletes to brainstorm solutions.

“This effort will take a village,” USOPC chief executive Sarah Hirshland told members during a recent videoconference. “We will not solve all of the issues all at once … but certainly we can start to chip away.”

Their agenda ranges from the practical (bottom-line economics) to the esoteric (discussions about how sports align — or should align — with higher education). These diverse issues intersect with America’s love for the Games and the unusual, often shifting, path the country has followed in nurturing athletes.

It’s all about the quest for gold.

::

The first time French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin invited the world to his new-fangled athletic festival, modeled after ancient Greek competitions, only a dozen or so nations showed up. From this 1896 debut, the modern Olympics slowly grew.

Americans never approached the Games like other countries where governments select and fund their teams. Early on, the U.S. sent a mishmash of college and private clubs, everyone wearing different uniforms. Two medals from the 1900 Paris Games belonged to a University of Pennsylvania student who was actually Canadian.

Then, in 1908, the American Athletic Union assumed control of organizing the roster.

“The AAU was a very big deal at the time,” says Mark Dyreson, an Olympic historian at Penn State University. “It was running every amateur sport in the country.”

For nearly five decades, the AAU remained the key to assembling squads that often led the medals table because of the U.S.’s population, prosperity and cultural affinity for playing games. But in the 1950s, as college sports became more prominent, the NCAA muscled in.

The rival organizations began squabbling over money, each hungry for a slice of appearance fees that American athletes earned at foreign events. They soon wrestled for control of the Olympic roster.

Into this drama barged the USSR, which had focused on sports as a means of boosting its international profile. The effort paid off with a victory in the medals count at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and in Rome four years later, the U.S. relegated to second place.

“There had to be a change,” Dyreson says. “We were losing to the Soviets.”

Congress eventually got involved and, in 1978, passed the Amateur Sports Act, giving the U.S. Olympic committee authority over the American squad. Olympic historian Bill Mallon says this forced the AAU into the background and shifted more influence to the NCAA.

An estimated 600,000 Tokyo Olympics ticket holders outside of Japan are fighting to get elusive refunds after they were banned from attending the Games.

By the mid-1990s, the USSR had dissolved and Americans once again prevailed. It did not matter that the medal count wasn’t really official or that it made traditionalists cringe — fans liked to see the U.S. on top with colleges supplying much of the talent.

“You’ve got that element of a pipeline,” says Rick Adams, USOPC chief of sport performance. NCAA teams offer “coaching, facilities, nutritionists, sports psychologists … all of the things we provide for Team USA but the college system provides it at hundreds of campuses.”

Nowhere else in the world are college sports played so avidly, in such numbers. This mechanism has continued to outpace the state-run model, with the Americans winning 121 medals in Rio de Janeiro five years ago, their most-ever for a widely attended, non-boycotted Games.

“There’s a lot of competition you have to go through” in college, wrestler Kyle Dake says. “I think it gives us an advantage as a country.”

::

College is not the only path to the Olympics. In sports such as gymnastics and swimming, athletes often peak as teenagers, honing their skills at elite private clubs. It’s the American version of the academy system.

Janet Evans took this route, earning three gold medals as a teenage swimmer at the 1988 Seoul Games. Still, upon returning home to Southern California, she enrolled at Stanford.

“It was appealing to me,” says Evans, who now works for the LA 2028 organizing committee. “I thought I would swim better.”

Coaching and facilities were only part of her decision. Evans and others talk about the benefits of maturing in ways that have nothing to do with sport.

“College allowed me to grow up as a young man,” says Quincy Watts, a USC alumnus and a two-time gold medalist in sprints. “I had dreams of being an Olympian but I needed to understand my goals.”

The list of Olympic greats who emerged from the NCAA includes Lewis, a University of Houston sprinter before he won nine golds, and Jackie Joyner-Kersee, who starred at UCLA on her way to six medals in heptathlon and long jump. May-Treanor helped Long Beach State to a collegiate title before joining with Kerri Walsh Jennings to form the most-decorated beach volleyball duo in history.

“You learn how to win, how to lose and how to compete during these very formative years,” USOPC executive Adams says. “By the time you reach the international level, you can fall back on that.”

As a senior at the University of Minnesota, Shane Wiskus has parlayed his college experience into a spot on the national gymnastics squad. With his school dropping the sport, he worries about the next generation.

“I think there will be an aspect of the competitive edge that will be lost,” he says. “It’s concerning and I don’t know if there’s an answer right now.”

::

Not everyone cringes at the prospect of NCAA schools cutting Olympic sports.

As founder of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program, Tom Farrey believes football and basketball have co-opted the college model, encouraging athletic departments to behave like NFL or NBA franchises, blindly chasing after television dollars.

“Colleges need to ask themselves, ‘What is the purpose of sports on campus?’” Farrey says. “’What will promote participation by the broadest swath of students at the lowest cost, in a form that promotes a healthy outcome?’”

The U.S. would consider a joint boycott with other countries of the 2022 Winter Olympics in China over human rights abuses, the State Department says.

Nonrevenue teams might better operate as student clubs supported by the university’s general fund, Farrey says. They might not have lavish facilities or athletic scholarships, but could hire coaches and compete in leagues organized by national governing bodies, such as USA Volleyball or USA Wrestling, that oversee each amateur sport.

The idea sounds reasonable to Travis Nitkiewicz, a Michigan State swimmer whose team will be cut this summer.

“Some athletes need the scholarship, but a lot of us just love to compete,” Nitkiewicz says. “I’m sure we’d be there regardless of the format, whether it’s NCAA or not.”

So far, the USOPC appears to be focused on less-radical changes.

Think tank members would like to see national governing bodies supply funding to college programs and establish regional training centers for teams that need facilities. There has been talk of holding NCAA events in conjunction with youth championships, splitting the venue cost and attracting more spectators.

Nonrevenue teams that escaped the latest cuts are looking to gird themselves by trimming budgets and raising outside funds. If anything, the pandemic has taught coaches to recruit by Zoom rather than fly around the country.

“We had a lot of coaches who thought their jobs were just using a stopwatch,” says Greg Earhart, executive director for a national swimming and diving association. “Now it’s about being an effective CEO.”

With the pandemic’s economic impact expected to linger, the clock is ticking. College teams must fight to survive while the U.S. Olympic program looks over its shoulder at new rivals.

The USOPC says U.S. athletes can raise a fist or kneel in protest on the medals stand. The International Olympic Committee has a rule against demonstrations.

“Take China, for example,” sprinter Johnson says. “They have a huge budget.”

Twenty-five years have passed since he made history by winning the 200 and 400 meters — wearing those golden spikes — at the 1996 Atlanta Games. He now consults nations hungry for that kind of glory. His clients can build facilities, hire coaches and develop training programs, but he believes they lack a key ingredient.

“I see it firsthand,” he says. “They can only go so far.”

Johnson is talking about a network of colleges working just beneath the elite level. If the NCAA continues to drop nonrevenue teams, the U.S. might become a little more like other countries in the way they identify and prepare Olympians. They might slip down the medals table.

“My fear is that you’re going to have athletes who have potential but get left behind,” he says.

Like the kid from Dallas who ran with his shoulders high, head thrown back. The one who got a second chance in college and ended up as one of the greatest Olympians in history.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.