Tommie Smith believes the time is right for athletes to protest at Tokyo Olympics

- Share via

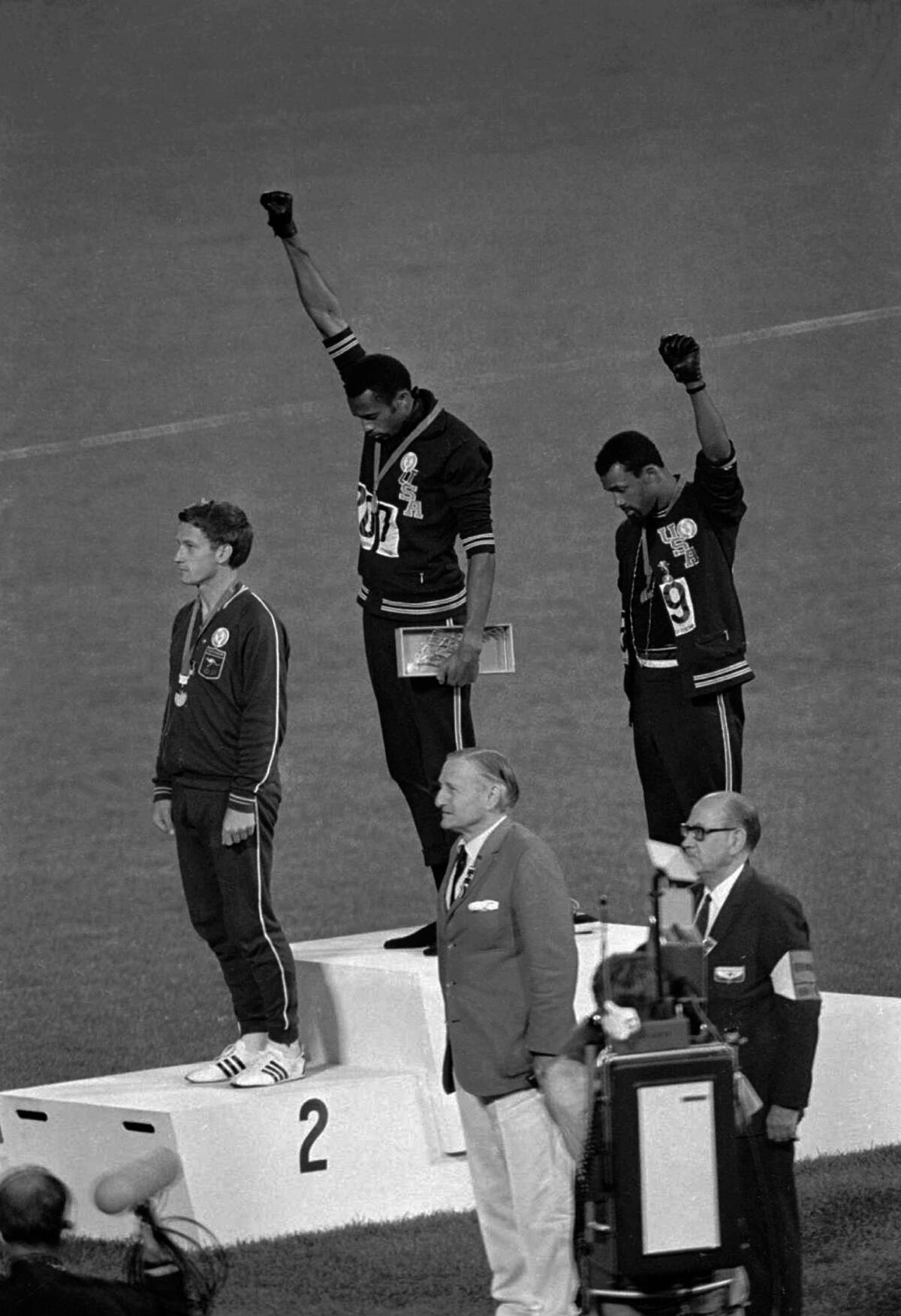

It’s one of the most iconic sports photos of all time.

Tommie Smith, clad in his blue USA track suit, a gold medal draped around his neck, stands ramrod straight atop the medal stand at the Mexico City Olympics, head bowed and his black-gloved right fist raised defiantly toward the heavens. Teammate John Carlos stands behind him, a bronze medal around his neck and his left arm, bent at the elbow, held above his head.

The actions of Smith and Carlos, who finished first and third in the 200-meter final, were designed to call attention to the poverty and the systemic racism Black Americans were subject to in 1968. Instead, it got them kicked out of the Games and stamped as pariahs even before they had even left Mexico City.

As the U.S. prepares to send a team to another Olympic Games this month, the conditions that Smith and Carlos were protesting have gotten worse, not better. The economic and home ownership gaps separating Black and white Americans is wider today than in 1968. The Black unemployment rate is also higher as is the number of Black students attending non-white schools. Voting rights for people of color are once again under assault.

So is it time for someone to follow in the two sprinters’ black-socked footsteps in Tokyo and use the platform of the Olympic Games to call for human rights? Smith thinks so.

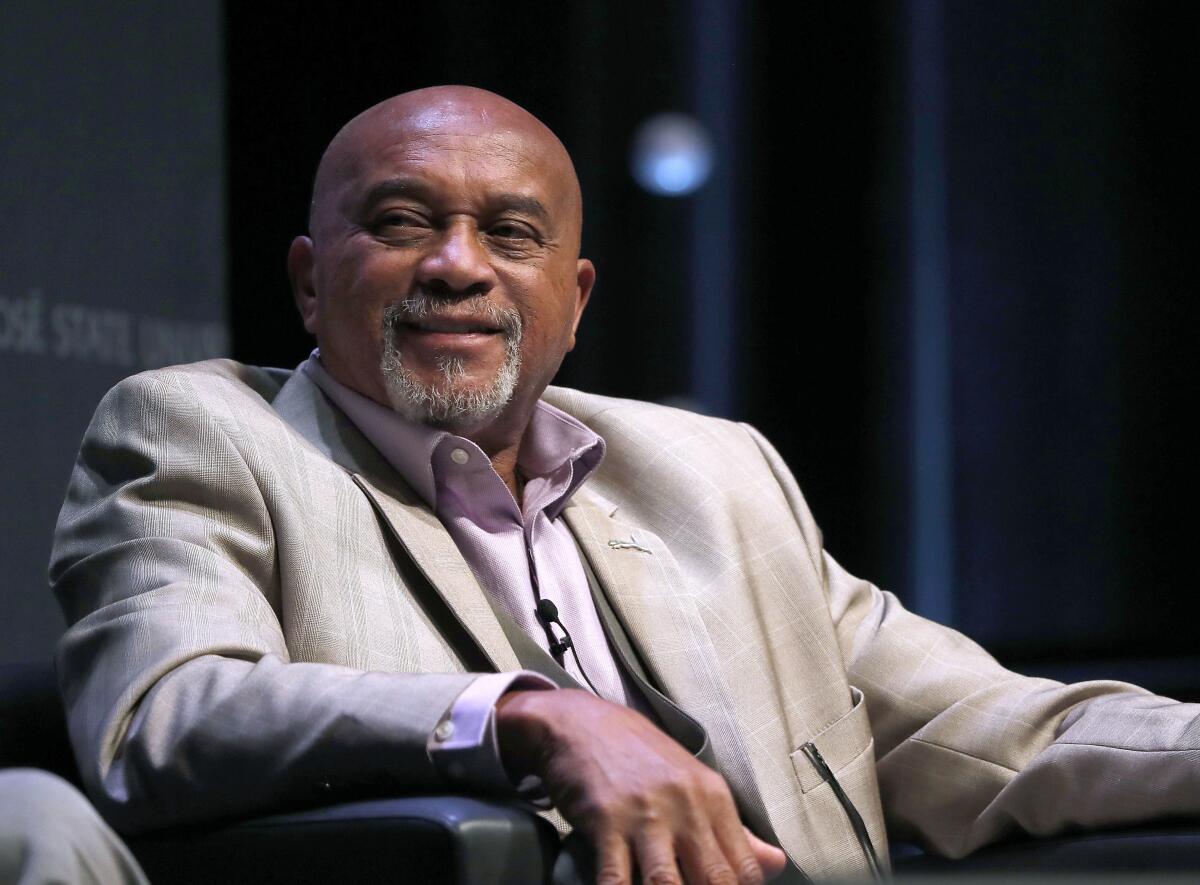

“It is better to say it and to get it out then not say it at all,” he said in a videoconference call from his home in Stone Mountain, Ga. “I do think the athletes have a right to say whatever is on their mind, whether it’s agreeable to those who are watching or it’s thought of negatively. We are human beings.”

The heavy price Smith, then 24, paid for his Olympic protest is told in the documentary “With Drawn Arms,” which will be available on Apple TV, Prime Video and other digital platforms starting Tuesday.

The timing seems prophetic.

Last Friday, after years of resisting, the International Olympic Committee updated its charter for the third time in 18 months to allow athletes to make limited political gestures “prior to the start of the competition” but not on the medal stand in Tokyo. Political expressions will also be prohibited “during the introduction of the individual athlete or team” and cannot be made “directly or indirectly against people, countries [or] organizations.”

In other words, nothing’s really changed. And that puts the IOC at odds with U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, which last year issued a four-page statement that said Rule 50 of the IOC charter, the one that still bans most political gestures, “violate[d] athletes’ rights to free speech and freedom of expression.”

As a result Gwen Berry, who finished third in the women’s hammer throw at the U.S. Olympic trials in Eugene, Ore, earning a ticket to Tokyo, was not sanctioned when she turned away from the flag as the national anthem played. If she does the same thing in Japan, she could be expelled for the Games, just as Smith and Carlos were 53 years ago.

“At that point in time, two individuals could make that statement. At this point in time, given what we’ve seen in terms of George Floyd and others, we need the continuation of massive standing up,” said Vickie Mays, a UCLA professor and director of the school’s center on minority health disparities, comparing the 1968 Mexico City protests with the decisions of WNBA, NBA and Major League Soccer players to support Black Lives Matter protests last summer.

“It’s very dangerous for the athletes when they stand out,” Mays continued. “And so I think only having a couple of people do it will allow people to ignore [it]. But having many do it—and it’s not a moment but it continues to be part of a movement —is much more effective.”

If the social conditions that led to the 1968 protest and the rules that got Smith and Carlos banned haven’t changed much, the power the athletes wield has. The vision of Smith’s raised fist atop the medal podium was powerful largely because it was unscripted and took place during the first Olympics broadcast live and in color around the world. Athletes of that era, however, while allowed to run fast and jump high, were not encouraged to share their opinions.

“What’s changed that’s relevant to Tommie and what they did in ’68 is they were alone, they were banished,” said Richard Lapchick, president of the Institute for Sport and Social Justice and chair of the sports business management program at the University of Central Florida. “Tommie and John couldn’t get a job in America for seven years. They were facing five years in prison.”

Indeed Smith, who broke 13 world records, his final coming in the 200 meters in Mexico City, received death threats, was briefly banned from competing and suffered economic hardship, two divorces and severe depression. That part of his story, as well as his rebound from those hardships, is also in the documentary, which is directed by Glenn Kaino and Afshin Shahidi and co-produced by Grammy-winning musician and philanthropist John Legend.

Also spotlit is Smith’s legacy. Now it’s unusual to see a sporting event in the U.S. start without a player taking a knee or wearing a T-shirt with a political message. Teams in five professional leagues boycotted games last year to protest the shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, by police in Wisconsin and dozens of college and professional athletes have taken part in Black Lives Matter protests.

“Opinion polls are showing sports fans, who I consider a fairly conservative group, are supporting athlete activism,” Lapchick said. “It’s masses of athletes standing up now, backed by teams, backed by leagues to some degree.”

Smith, 77, saw his career end when he took his stand at the Olympic Games. Fifty-three years later, in the documentary, he was asked if he had any regrets.

“No,” he says, “but I can give you a reason why it could have been very regretful. It’s me having to do it at all.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.