Editorial: The new world of voter suppression

- Share via

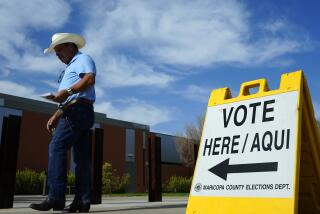

A week from Tuesday, voters will choose an entirely new House of Representatives, a third of the U.S. Senate and the governors of 36 states. Lamentably, many qualified voters will stay home, some out of apathy or disillusionment but others because they lack the right sort of identification. In Texas, thanks to an outrageous order by the Supreme Court, voters will have to display a photo ID under a law that a lower court judge concluded was a deliberate attempt to disenfranchise blacks and Latinos, who disproportionately lack such identification.

Welcome to the new world of voter suppression, the culmination of a sustained effort by mostly Republican state legislators to make it harder for Americans to exercise the most basic right afforded to citizens in a democracy. It’s an effort whose effect, if not its intent, has been to reduce the participation at the ballot box by groups that historically have been the victims of discrimination. It has been abetted by a Supreme Court that blithely gutted an important section of the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act and by a Congress that has been to slow to undo the damage caused by the court.

What is most galling about the wave of photo ID laws is that they have been justified by high-minded Republican arguments about the importance of rooting out voter fraud, which indeed would threaten the integrity of the electoral process — if it existed. But impersonation at the polling place is an exotic if not imaginary phenomenon. In her decision invalidating Texas’ photo ID law, U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos noted that the record showed only four instances of impersonation in Texas.

Despite Ramos’ conclusion that Texas’ photo ID violated the Voting Rights Act and the U.S. Constitution, voters there on Nov. 4 will have to present a photo ID anyway. That’s because the U.S. Supreme Court refused to lift a stay placed on Ramos’ decision by a federal appeals court pending an appeal.

Meanwhile, voters are being inconvenienced — and worse — by other laws that make it harder to vote. And the Republican Party shows no sign of relenting in its campaign to make voting more difficult, especially for the low-income and minority voters who tend to support Democrats.

What can be done?

The Supreme Court bears considerable responsibility for the obstacles being placed in the way of voting, and it could do much to remove them. In 2013, a narrow, five-member majority declared unconstitutional the formula in the Voting Rights Act under which states with a history of racial discrimination in voting had to “pre-clear” changes in their election procedures with the Justice Department or a federal court in Washington. The majority thought the formula relied too much on out-of-date information, but under the Constitution that was Congress’ call to make. Before the court’s decision, a federal court had blocked the Texas law.

The court is unlikely to revisit its decision about “pre-clearance” of elections laws. But it could redeem itself somewhat by rethinking the approval it extended to photo ID laws in a 2008 decision from Indiana. In the lead opinion in that case, Justice John Paul Stevens exaggerated the justification for the photo ID requirement while minimizing the hardship incurred by voters who lacked IDs. Subsequent events have vindicated the dissenters in that case.

But whether or not the court acts, Congress can move to rein in voter suppression. This year, Sen. Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.) and Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) proposed legislation that would provide for pre-clearance of election procedures in any state with a history of discrimination. That would go a long way toward reinvigorating the Voting Rights Act. But one section of the bill exempts photo ID requirements from its list of violations. That loophole must be closed.

The problem, of course, is that congressional action to prevent the use of photos IDs to suppress the vote would require Republicans in Congress to distance themselves from the tactics of their counterparts in state legislatures around the country. But with the 2016 presidential election approaching — an election in which the GOP nominee may need a modicum of support from the very same minority voters the party has been trying to marginalize— support for easier access to the ballot box might be good politics as well as good government.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.