As with vaccines, equity becomes an issue with COVID-19 medicines

- Share via

Under pressure from a virus that has killed close to 900,000 Americans, researchers have developed a clutch of lifesaving treatments that reduce the risk of severe COVID-19 by as much as 89%. But there aren’t nearly enough of the new drugs to go around. And if recent pandemic history is any guide, the patients who are getting them are probably whiter, richer and healthier than the ones who aren’t.

States, counties and healthcare systems are struggling to mete out their limited supplies without making existing disparities worse. Some are trying to prevent this by taking the race and ethnicity of patients into account — and courting controversy in the process. The Biden administration has offered little guidance.

For the record:

12:45 p.m. Feb. 8, 2022An earlier version of this story said California created the Healthy Places Index to gauge the socioeconomic well-being of a community. That index was developed by the Public Health Alliance of Southern California, and state officials adapted it to create their own health equity metric.

4:22 p.m. Feb. 4, 2022An earlier version of this story misspelled JP Leider’s last name as Lieder.

Just over a year ago, the rollout of vaccines raised similar concerns: that high demand and scarce supplies would leave low-income communities and people of color waiting — and dying — for their shot. Though the federal government’s experts urged steps to address equity, early distribution efforts by the states largely disregarded those calls.

“It’s pretty clear we haven’t learned that lesson,” said Harald Schmidt, a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. The federal government can recommend and pay for measures meant to make access to healthcare fairer for all. But unless states choose to adopt them, the marketplace will decide who gets them first, and the result will rarely be equitable, he added.

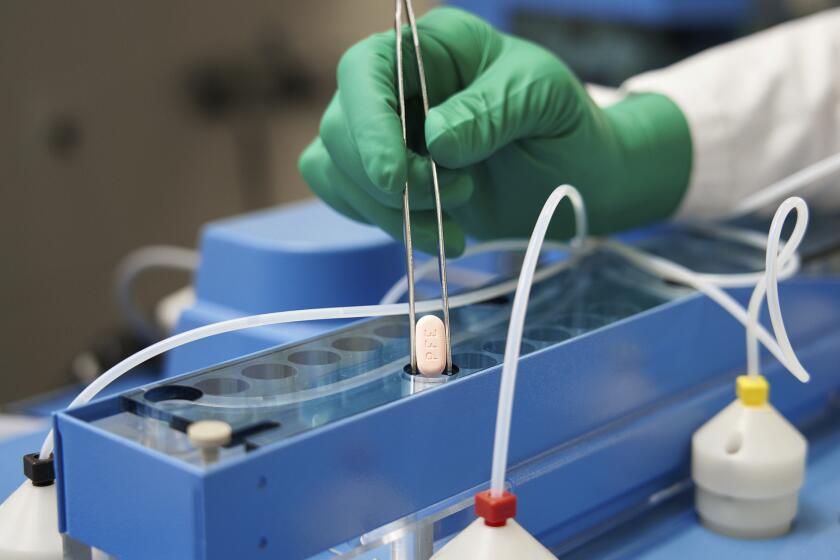

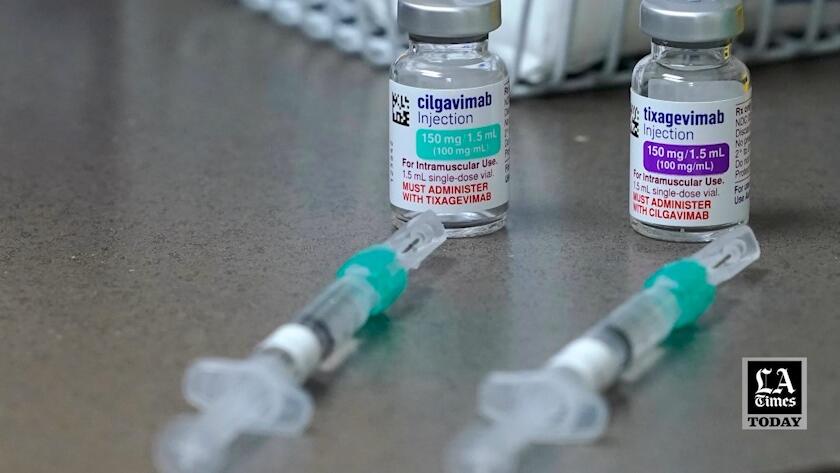

The new drugs are as hard to get as they are difficult to pronounce. Paxlovid and molnupiravir are antiviral medications for patients with newly detected coronavirus infection who are at high risk of becoming severely ill or dying. Sotrovimab is a monoclonal antibody therapy for the same group of patients. Evusheld is another monoclonal antibody infusion that helps fend off infection in patients who don’t gain much immunity from vaccine, or for those who can’t take vaccine.

All of them are trickling out of a government pipeline in quantities that fall well short of demand.

Two brand-new COVID-19 pills that were supposed to be an important weapon against the pandemic in the U.S. are in short supply.

In the first four weeks of the year, a period when 20.5 million new infections were reported, the federal government distributed enough Paxlovid and molnupiravir to treat just under 1 million patients. States have received a little more than 200,000 courses of sotrovimab, the only monoclonal antibody that’s effective against the Omicron variant. And fewer than 300,000 doses of Evusheld have begun reaching hospitals to protect a vulnerable population that numbers between 10 million and 17 million.

“It’s not even scratching the surface” of the need right now, said JP Leider, a University of Minnesota ethicist who has helped design a lottery system for the scarce COVID-19 medications in that state.

President Biden has promised that bigger supplies of all the drugs are coming. In the meantime, Washington has set aside a fraction of each drug’s supply — about 15% — to send directly to a network of 1,368 federally qualified health centers that operate in poor and underserved communities across the country.

But the bulk of the medications are being distributed to states to apportion as they see fit, Leider said. And many states and counties are distributing them in ways that effectively give dibs to the medically eligible patients who get in the door first.

That’s allowing a lot of doses to be diverted from the patients who are most at risk of severe illness or death from COVID-19 to better-heeled patients who are not, Schmidt said.

One of the hallmarks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is that it disproportionately strikes people of color. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

The pandemic has set in relief a hard fact of medical care in the United States: In a first-come, first-served system, the more affluent, better-insured and more highly educated will muster quickly at the front of the line. Poorer, more socially vulnerable patients — including a disproportionate number of people of color — will be left waiting behind them.

The result can be tallied in deaths. Americans who live on the bottom third of the nation’s socioeconomic ladder have been 48% more likely to die of COVID-19 than those in the top third. And people of color are much more likely than whites to fall in that bottom third.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that in any age group, Black Americans, Latinos and American Indian and Alaska Native people have been roughly twice as likely as their white peers to die of COVID-19. Only Asian Americans have fared better than whites, with a 10% lower risk of death.

The use of monoclonal antibodies in newly infected patients to head off a severe case of COVID-19 offers a good example of a system that leaves people of color at a disadvantage. A January report by the CDC COVID-19 Response Team found that in a 10-month period ending in August, Latinos who tested positive for a coronavirus infection were 58% less likely than similar non-Latino Americans to receive the antibodies. In addition, newly infected Black people were 22% less likely than their white counterparts to get the treatment, the report found.

Once patients were sick enough to be admitted to a hospital, racial and ethnic disparities in the use of COVID-19 treatments virtually disappeared. To the report authors, that suggested Latino, Black and Native Americans face hurdles that aren’t as prevalent for white Americans. Many lack a primary-care doctor to recommend and prescribe the therapy, the time and transportation to go and get it, and the health insurance to fully cover it.

Even when the antibody treatment is offered, a lack of trust in the medical establishment — borne of historical injustice and often personal experience of bias — prompts many people of color to take a pass.

It’s not just the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, Black Americans’ skepticism about COVID vaccines is fueled by health inequities they face now.

A system that forces disadvantaged patients to compete with the affluent for access to scarce drugs “is a terrible strategy,” said Dr. Douglas B. White, a bioethicist and critical care doctor at the University of Pittsburgh who helped design Pennsylvania’s lottery system for the allocation of COVID-19 drugs.

For instance, he said, many states opted to distribute the highly effective and sought-after drug Paxlovid only to retail pharmacies, rather than making it widely available in hospitals and clinics. The result has been a free-for-all rigged in favor of people who not only know about the drug in the first place but have ready access to doctors — who must prescribe it — and the means to track down a pharmacy that has it in stock.

“The wealthy and well-connected will win the race,” White said. It’s “the poster child for an unfair system.”

But many efforts to promote fairer access have sparked a backlash. New York City is facing a legal challenge over its guidelines to healthcare systems, which include race and ethnicity among many other risk factors. Legal action is also threatened against Minnesota, which briefly employed a similar system. The state discontinued that policy in January in favor of a lottery that considers a broad measure of patients’ socioeconomic status.

California devised its own broad measure of a community’s socioeconomic well-being to make the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines more equitable back when demand far outstripped supply. That health equity metric, adapted from a measure called the Healthy Places Index, now governs the distribution of coveted COVID-19 medications.

It makes no reference to race or ethnicity. Instead, it focuses on such factors as housing density, poverty, education levels, environmental factors and access to supermarkets and healthcare in given neighborhoods.

Health experts hope to nudge people of color to the front of the COVID-19 vaccine line without explicitly saying race, ethnicity influence priority.

The state’s allocations of the antibody sotrovimab are based on where new cases and new hospitalizations are highest, a spokesman for California’s Department of Public Health said.

The absence of explicit reference to race and ethnicity in the state’s health equity metric is no accident, Schmidt said: It has helped California steer clear of a third rail in American politics.

Former President Trump has stoked those passions in recent weeks. “The left is now rationing life-saving therapeutics based on race,” he told supporters at a rally in Florence, Ariz., last month. And in New York, he charged, “If you’re white, you have to go to the back of the line to get medical health.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.