Opinion: How should we deal with COVID now?

- Share via

This month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released new COVID guidelines ending the five-day isolation recommendation. The agency now advises staying home only if you have symptoms, such as fever. Otherwise, you can return “to normal activities” if, for at least 24 hours, your symptoms are improving overall and any fever has gone away without the use of fever-reducing medication. The official announcement follows unconfirmed reports in February of this change.

As is often the case with COVID-19, the news has started a back-and-forth as to whether the latest government rules are too strict or too loose. Our approach to the virus as endemic remains uneasy as the annual death toll, estimated at below 70,000 in 2023, drops closer to but remains significantly higher than the toll of the flu.

Some experts have questioned the policy shift, since there is no new science strongly defining COVID’s contagious period by an active fever. Others have supported the agency’s goal of making COVID-19 guidelines “easy to understand” and follow, aligning them with recommendations for other seasonal viruses. Many, including me, want to see flexibility for high-risk environments such as hospitals and nursing homes to implement more conservative guidelines, with longer isolation periods and lower thresholds for staying at home.

But these conversations dodge many of the realities of COVID-19 in this phase. While we continue to debate ways to shape individual human behavior for collective protection, we’re squandering some of the resources we’ve already put toward fighting this disease.

More parents are choosing to delay childhood vaccinations, such as the MMR vaccine. Doctors worry toddlers remain vulnerable as measles spreads.

Vaccination got us past the worst of the pandemic, yet now we’re under-using it to control COVID-19 and, more importantly, reduce deaths. In the United States, immunization rates for the recommended boosters remain low even in high-risk groups, such as older adults and the immunocompromised. As of early March, the rate among those 60 years or older was 42% (and just 23% for all adults eligible for the latest version of the vaccine).

The reasons for this extend well beyond the often-blamed mistrust in science. For one thing, we’re missing opportunities to vaccinate people who might not on their own pursue a shot. Inoculation should be easily available to those who show up at health facilities for whatever reason — testing, routine care, emergencies — and would be open to being vaccinated then. There are also people who could still be persuaded into getting boosters. Doctors, nurses and other healthcare providers remain the most trusted sources of vaccine information. A strong recommendation from a provider makes it more likely that a patient will get a vaccine.

Counseling patients about vaccines requires providers’ time. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimburses physicians if they counsel certain patients, or their caregivers, about receiving a recommended vaccine even if the patient declines the vaccine that day. This provision covers beneficiaries of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. But for most other insurers, vaccination costs are reimbursed only if a patient ends up getting vaccinated, which providers won’t know before giving counsel. Not consistently making vaccine counseling reimbursable, unlike, say, nutritional counseling, disincentivizes healthcare providers to spend the time needed.

Thanks to the newly dominant strain JN.1, about 2 million Americans are getting infected each day.

The chaos of healthcare expenses creates further obstacles. The U.S. reimbursement system is primarily designed for treatment, not prevention. After the federal government stopped directly covering the cost of the vaccine, it fell to the patchwork of largely insurance-based payers. People have found it hard to navigate the new payment process.

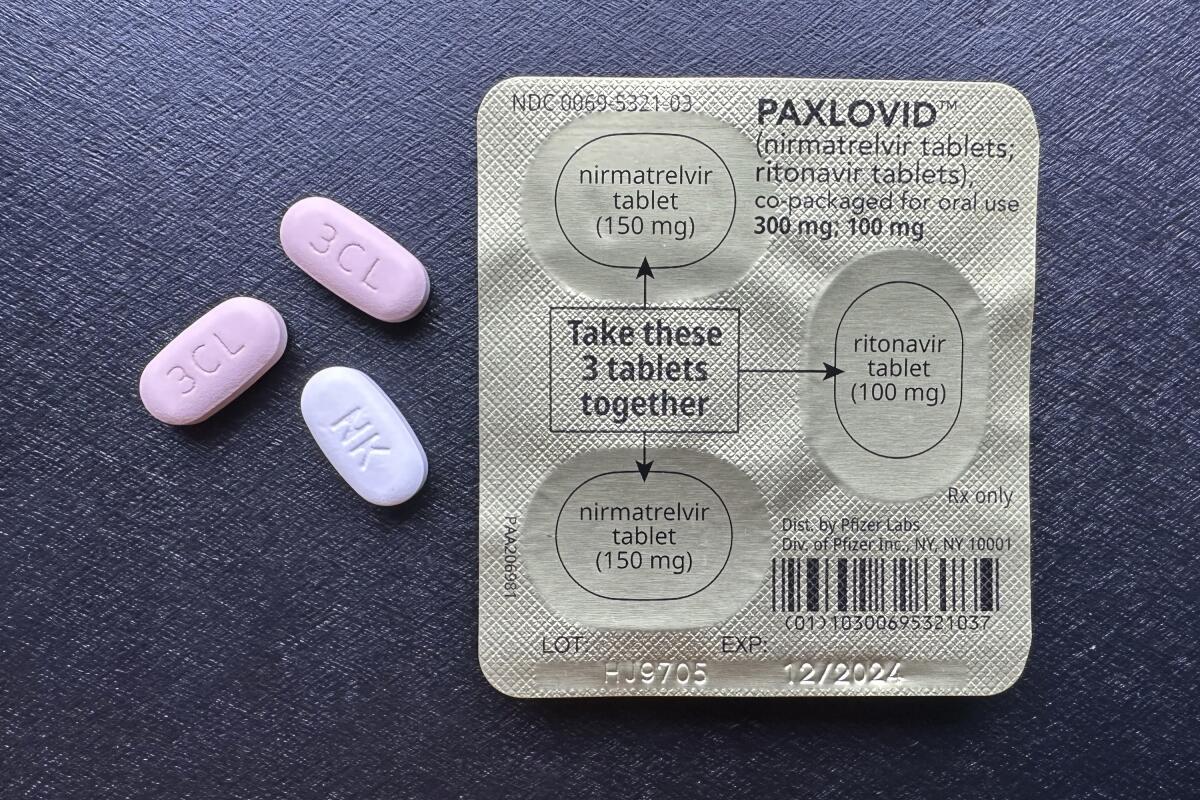

Another payment problem arises around antiviral medications such as Paxlovid — imperfect but useful tools to reduce death among those infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The drugs are most useful if administered soon after infection, and Pfizer set the out-of-pocket price for a five-day course at $1,390. After the COVID-19 public health emergency ended, the Department of Health and Human Services reached an agreement with Pfizer to increase access through the Paxcess program, which ensures that the drug is free for those on Medicaid and Medicare and the underinsured. There’s also a copay assistance program for others who cannot afford the drug.

Unfortunately many people, including pharmacists, are not aware of this program. Access to a mortality-reducing drug should not be a well-kept secret. The Department of Health and Human Services should embark on an expanded pharmacist and healthcare provider information initiative, working with all major pharmacy chains, to add electronic prompts for Paxcess to prescription fulfillment systems.

Another underused COVID resource: improved indoor ventilation and air filtration. These interventions include increasing indoor airflow through mechanical means (such as modification to HVAC systems) or natural means (such as keeping the windows open); proper filtration of circulating air through air cleaners or through heating, ventilation and air conditioning; and installing ultraviolet irradiation equipment to kill viruses.

Fortunately, there is federal funding available for locations with high population density, including schools, to improve indoor air quality. But far too few have since upgraded their ventilation and air filtration systems. More use of that funding, alongside support from the private sector, could make buildings healthier.

These meat-and-potatoes approaches — vaccination, access to treatment and clean air — may not be the most exciting tools. But they reflect the best of public health: strategies that are so effective they almost invisibly reduce life-threatening illness.

Saad B. Omer is an epidemiologist and vaccine expert.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.