Why a fast-spreading coronavirus and a half-vaccinated public can be a recipe for disaster

- Share via

If you were responsible for tracking the pandemic, divining what the coronavirus’ next trick will be, and keeping illness and death to a minimum, you’d be really worried right now.

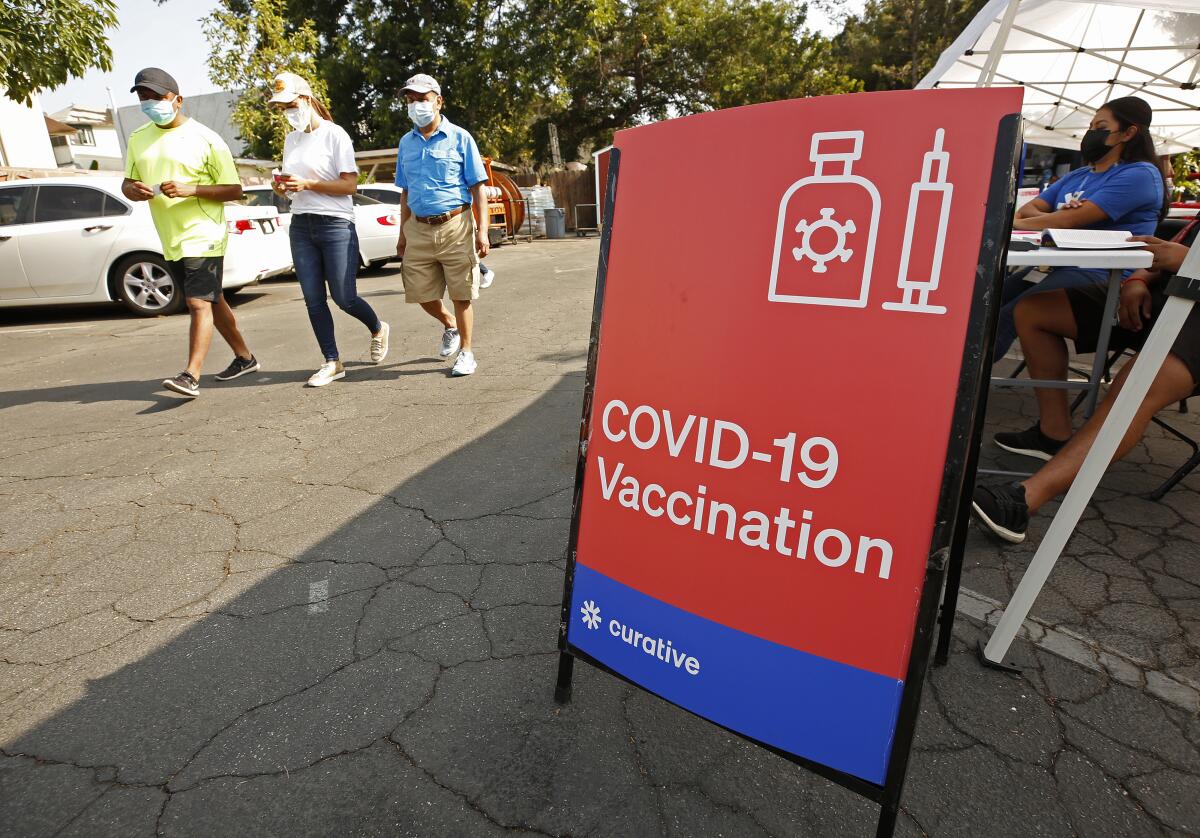

The COVID-19 vaccines are making a difference, and they’ve prevented nearly all recipients from becoming very sick or dying. But with infections surging among the unvaccinated, hospitalizations reaching a height not seen since February, and just half the population fully inoculated, the coronavirus is not done with us yet.

And new perils lie in wait that could escalate or prolong the outbreak. Each has the potential to cause more illness and death. And if they happen in combination with each other, the misery could be compounded.

Here’s a closer look at why scientists fear we may be approaching another tipping point in the pandemic.

Conditions are ideal for the emergence of vaccine-resistant variants

Fear of the Delta variant has fueled a long-awaited uptick in vaccinations. In roughly the last four weeks, about 12 million Americans have rolled up their sleeves for a first dose of vaccine. That’s good news.

But there’s also a dark side to the stampede of vaccine latecomers: Millions of people are now partially vaccinated. One authoritative study estimated that a single shot of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is about 33% effective against the Delta variant, far less than the 90% protection conferred by two shots. So with a highly transmissible strain on the loose, some of the newly vaccinated are bound to become infected before they acquire fuller immunity.

The Delta variant is more formidable than previously believed, due to its ability to infect and be spread by people who are vaccinated, a CDC document says.

Meanwhile, close to 3% of American adults — about 7 million people — are thought to have compromised immune systems, and many of them are likely to have had an incomplete immune response to the vaccine. As a practical matter, until they get a booster shot, they’re partially vaccinated too.

These conditions of incomplete viral suppression ratchet up the evolutionary pressure on a virus. Faced with a wall that’s only half built, the virus that finds a way to jump is rewarded. Mutations that help it do so have a better chance of surviving to infect someone else.

This is how new viral strains are born. Scientists have documented that immune-compromised patients who can’t quickly clear a SARS-CoV-2 infection are prolific generators of new viral mutations.

By the same biological reasoning, people who are between their first and second vaccine doses are also at risk of incubating mutations that could produce new variants — especially ones that allow the virus to dodge the protection provided by vaccines.

COVID-19 patients who take months to overcome their coronavirus infections despite treatment can become incubators of dangerous new strains.

“This is what RNA virus do — it is their fundamental biological property,” said Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccinologist at the Mayo Clinic. “Particularly in the face of partial immune pressure, the virus will figure out a way to evade it. And then everybody’s back at the beginning.”

Said Dr. Megan Ranney, associate dean of Brown University School of Public Health: “This situation we’re in, where half of us are fully vaccinated and half are not, you couldn’t design a better experiment for creating a vaccine-resistant variant.”

Surges create super-spreader events that can propel new variants into high circulation

RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 mutate frequently because their replication program fails to fix many of the mistakes that arise when they make copies of their genetic code.

Still, the resulting variants typically don’t travel far from the host in which they’re spawned. They might have dangerous new capabilities, but they very rarely enter into broad circulation because the person in whom they incubated isolated herself, or wore a mask, or was lucky enough not to infect anyone.

Studies of variants’ spread in populations, as well as models of their emergence, have demonstrated that new viral strains have a better chance of making their way into broader circulation when cases are surging. The brisker the spread, the more chances a variant with enhanced capabilities has to springboard into broader circulation.

A new study shows that even a coronavirus variant that’s built to transmit won’t get very far if it doesn’t have the good fortune of meeting a superspreader.

Encountering a “superspreader” event in the weeks following its birth gives a variant its best chance at taking off, a modeling study found. If its carrier can spread it to just five people, it will have enough momentum to compete for more victims. Infecting 20 or more people in a single go would give it a real chance of dominating its new community.

“We will in all likelihood create new variants on top of those that have emerged,” said Dr. Joshua T. Schiffer, who led the modeling team at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

That the United States is in the midst of a new surge of infections is clear. And across the country, potential superspreader events — at schools, shopping centers, restaurants, gyms, church services and even motorcycle rallies — are routinely mixing vaccinated, partially vaccinated and unvaccinated people in close quarters with spotty masking.

Kids are going back to school amid high levels of community transmission with incomplete vaccine protection

Throughout most of the pandemic, kids weren’t thought to be key drivers of spread. That may be changing.

Across the country, the average age of people being hospitalized with COVID-19 is dropping. Each day for the first week of August, an average of 203 kids under 18 have been admitted, just a notch less than the peak of 217 per day reported during the early weeks of January 2021.

Research has not yet established that the Delta variant affects kids differently than earlier strains. But it’s clear that larger numbers of them are becoming infected by it, and that has meant more kids getting sick. And as they make up a larger share of pandemic patients, they are playing a key role in keeping the pandemic alive.

A boom in COVID-19 hospitalizations for children has been driven by states like Florida, Texas and Georgia, but the numbers in California have been less dire.

Fewer than 5% of adolescents ages 12 to 18 have been fully vaccinated, and older teens’ propensity to spread the virus is thought to be more like that of adults than like younger children. The vaccines aren’t yet authorized for children 11 and under.

Schoolchildren have begun returning to classrooms anyway. In some of the places where case rates are highest, they’re doing so without face coverings. (Governors of some states have forbidden school districts from imposing mask mandates.)

Given the Delta variant’s high transmissibility and the low levels of vaccination across broad swaths of the country, Poland would expect cases to keep climbing. Add in 56 million K-12 students — most of them unvaccinated and many of them maskless — who huddle in classrooms and busses and then return to their families, and those prospects grow even higher, he said.

A surge in infections linked to school reopenings “can’t not happen,” Poland said.

The vaccines may wear off soon for healthcare workers, the first group to get the shots

Although COVID-19 vaccines have made a profound difference in the United States, the duration of the immunity they confer is a major unknown. Even without the emergence of a vaccine-resistant strain, the degree of protection is expected to wane with time.

In late July, Pfizer-BioNTech researchers reported that their vaccine’s efficacy against symptomatic disease had slipped from 95% to 84% after six months.

The Delta variant of the coronavirus has taken on a decidedly American feel, mainly targeting those who just won’t get vaccinated.

How will we know when that starts to happen? In the U.S., one of the first clues will be rising infections in healthcare workers and other groups that were vaccinated early. In Israel, there’s already early evidence that vaccinated doctors and nurses are developing breakthrough cases in greater numbers, though waning immunity may only be one factor.

Hospitals are once again filling to capacity just as depleted healthcare workers are leaving their jobs in droves. That means the effects of waning vaccine immunity could become evident at the worst time possible, amid an onslaught of unvaccinated COVID-19 patients, the return of patients who deferred care during the pandemic, and the resumption of injuries and illnesses that come with a reopened country.

Winter is coming

Respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 prefer a little less humidity than summer weather affords. And they spread better when there’s little space and not much airflow between their host and their next victim. Both of those wishes are granted as the weather outside cools and we spend more time indoors.

The onset of winter across much of the United States was a key contributor to the devastating surge that began last fall and peaked in January.

This fall, if ventilation is poor and people are packed closely together without face coverings, the Delta variant — which has been shown to replicate robustly in the upper respiratory passages of unvaccinated and vaccinated people alike — will find ample ways to spread.

Much of the rest of the world is unvaccinated, and likely to remain so for some time

As the Delta variant’s origins in India make clear, even a country like the United States with a plentiful supply of vaccine is not safe as long as the rest of the planet is contendingwith continued waves of pandemic illness.

Booster moratorium, or booster momentum? WHO chief’s call to ease vaccine disparity draws mixed response

Considering that less than one-third of the world’s population currently has access to the COVID-19 vaccine, there’s not only a humanitarian argument for getting more vaccine to countries that have gone without, said Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy. There’s a practical argument too.

“It’s about strategically protecting our vaccines,” he said.