New COVID subvariant XEC poses potential threat heading into winter

- Share via

- XEC, which was first detected in Germany, is gaining traction in Western Europe

- There are estimates that XEC makes up 13% of coronavirus samples in Germany and 7% in Britain. Will America be next?

A new coronavirus subvariant is gaining steam and drawing more attention as a potential threat heading into late autumn and winter — a development that threatens to reverse recent promising transmission trends and is prompting doctors to renew their calls for residents to get an updated vaccine.

XEC, which was first detected in Germany, is gaining traction in Western Europe, said Dr. Elizabeth Hudson, regional chief of infectious diseases at Kaiser Permanente Southern California. Like virtually all coronavirus strains that have emerged in the past few years, it’s a member of the sprawling Omicron family — and a hybrid between two previously documented subvariants, KP.3 and KS.1.1.

Past surges have tended “to move from Western Europe to the East Coast to the West Coast of the U.S.,” Hudson said. “So if this does take off more and more as we get towards the colder weather months, this probably would be the variant that will potentially take hold.”

XEC hasn’t been widely seen nationally so far. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, KP.3.1.1, a descendant of the FLiRT subvariants, is the dominant circulating strain nationwide. For the two-week period ending Sept. 14, KP.3.1.1 was estimated to comprise 52.7% of the nation’s coronavirus specimens.

Doctors and scientists are keeping an eye on yet another coronavirus subvariant — XEC — that could surpass the latest hyperinfectious strain.

XEC, by comparison, isn’t yet being tracked on the CDC’s variant website. A subvariant needs to make up an estimated 1% or more of coronavirus cases nationwide to qualify.

But there are estimates that XEC makes up 13% of coronavirus samples in Germany and 7% in Britain, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious diseases expert.

“We’ll have to see how things go. If this does take off, probably we would start to see it more like November, December time,” Hudson said. “So like after Halloween — when the weather will probably get more reliably cool here, people start to go indoors more often — that’s when we’re more likely to see this potentially take hold.”

Any fall or winter resurgence, which has become a reliable occurrence ever since the emergence of COVID-19, would follow a prolonged summer surge that surprised doctors and experts with its strength.

California’s COVID summer may no longer be heating up — though officials caution the virus continues to circulate at levels high enough to pack a punch.

One silver lining, though, is that the timing and strength of the summer COVID surge probably means it could be a couple of months before many people become more susceptible to reinfection, Chin-Hong said.

Last winter’s COVID peak in California — in terms of viral levels in wastewater — was the first week of January.

After the surprisingly strong summer surge, COVID is now declining or probably declining in 22 states, including California and Texas, as well as the District of Columbia, the CDC said Friday.

The COVID trend is stable or uncertain in another 22 states, including Florida and New York. COVID is projected to be growing or probably growing in New Jersey, Washington and Massachusetts, and there was no data for the three remaining states.

Still, new COVID infections remain relatively high in many parts of the country. Coronavirus levels in wastewater are still considered “high” or “very high” in 40 states, including California, Texas, Florida, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio, the CDC said Friday. They were categorized as “low” or “minimal” in six states, including New York, Michigan, Nevada and Hawaii.

California’s strongest summer COVID wave in two years is still surging, fueled in part by the rise of a particularly hyperinfectious FLiRT subvariant known as KP.3.1.1.

In Los Angeles County, coronavirus indicators are on a downward trend. For the 10-day period that ended Sept. 7, the most recent available, coronavirus levels in wastewater were at 56% of last winter’s peak. That’s down from the 10-day period that ended Aug. 24, when viral levels were at 75% of last winter’s peak.

An average of 239 coronavirus cases a day were reported for the week that ended Sept. 15, down 31% from the prior week. Officially reported coronavirus cases are an undercount, as they don’t factor in tests done at home or account for the fact that many people aren’t testing at all when sick. But the trends are still useful in determining how a COVID wave is progressing.

The share of emergency department visits classified as coronavirus-related in L.A. County was 2.8% for the week that ended Sept. 15, down from 3.5% the prior week.

The average number of COVID-19 deaths, however, is rising — an expected development given the surge in illness and the lag in reporting fatalities. An average of 4.9 COVID deaths were reported per day for the week that ended Aug. 27 in L.A. County, up from the prior week’s number of 4.3.

This past winter, the mortality rate for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 was 35% higher than for patients hospitalized with the flu.

COVID levels in the wastewater of the San Francisco Bay Area are also settling down. Coronavirus levels were considered medium in the sewersheds of San José and Palo Alto, and low in Sunnyvale and Gilroy, the Santa Clara County Public Health Department said.

The rate at which coronavirus tests are coming back positive is falling in California. For the week that ended Sept. 16, 8.9% of reported coronavirus tests — typically those done at medical facilities — returned positive results. The seasonal peak was 12.8%, for the week that ended Aug. 10, according to the latest data.

It remains unclear how bad this winter’s respiratory virus season will be. COVID isn’t the only game in town, as health officials also are closely monitoring flu and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV.

The CDC in late August forecasted that this fall-and-winter season will either be similar to last year, or perhaps slightly less potent. But that forecast could be overly optimistic, the agency warned, if some assumptions are off — such as if fewer people get vaccinated than expected.

The CDC says September and October are generally the best times for most people to get a COVID shot, though there are other factors to consider.

The situation may be improved because people may still have some residual immunity from flu and RSV, Chin-Hong said, which flared up the past couple of winters. Also helping matters is the rollout of vaccines against RSV, which became available last year.

Still, every winter carries its own respiratory illness risk. Circulation of a type of flu that’s different than the ones included in the vaccine would make those shots less effective, for instance.

And the experience from parts of the Southern Hemisphere for their winter suggests the respiratory virus season could be active here, Hudson said.

“Australia — they had a pretty robust and early flu season, and we are already starting to see a couple of cases of flu here in the U.S., which is pretty darn early,” Hudson said.

Doctors urge people who are experiencing respiratory problems to see a medical professional who can check their symptoms and test to determine what their illness is.

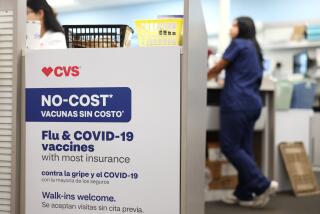

The CDC recommends that everyone 6 months old and older get the updated COVID-19 and flu vaccines. The immunizations are widely available, and the best time to get vaccinated is in September and October, the CDC says.

After a coronavirus infection, people may consider waiting three months to get the latest COVID vaccination, according to the CDC. But people can also choose to get it as soon as they feel better.

“I always have hope. And if folks get vaccinated — this is the perfect time now to get vaccinated against flu, get the new COVID shot — we could potentially tamp down on what will certainly be another more typical fall-and-winter surge. But I think the jury is out in terms of how bad it is going to be,” Hudson said.

Getting vaccinated “means fewer sick days and more time with your loved ones. We are stronger when we are all protected against respiratory diseases,” Dr. Tomás Aragón, the director of the California Department of Public Health, said in a statement.

Older or immunocompromised people who haven’t been vaccinated in more than a year are at highest risk for severe COVID illness and death, officials say.

Data show that people who got last year’s updated COVID vaccine were 54% less likely to get the disease between mid-September 2023 through January, according to the CDC.

A flu vaccine that’s well matched to the circulating viruses can also reduce the likelihood of becoming sick enough to require a doctor’s visit — by 40% to 60%, the CDC said.

There are needle-free options for getting the flu vaccine, such as FluMist, which has been available for many years as a nasal spray for non-pregnant people ages 2 to 49. On Friday, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved at-home use of FluMist — meaning adults can administer the vaccine to themselves or their children.

A prescription will still be needed for the at-home option, which is expected to be available starting fall 2025.

COVID remains a greater risk to public health than the flu, the CDC says. Since Oct. 1, at least 55,000 COVID-19 deaths have been reported nationally. At least 25,000 flu deaths are estimated over that same time period. Flu death estimates are expected to be updated in October or November.

The CDC recommends RSV vaccinations for all adults age 75 and older, as well as those ages 60 to 74 who are at increased risk for severe disease. The RSV vaccine, however, is not annual, so people who got one last year don’t need to get another one at this time.

Amid the winter respiratory virus season, a shot approved to combat respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, for infants and toddlers is proving hard to come by.

An RSV vaccine is also available for expectant mothers at weeks 32 to 36 of pregnancy to pass protection to their fetuses. An RSV antibody is available for babies and some young children, too.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said it will again make four free COVID tests available through the mail for households. You can register at covidtests.gov starting at the end of September.

Besides getting vaccinated, California health officials urged people to take other steps to prevent getting sick and infecting others. They include staying home when sick, testing for COVID and flu if you’re sick, wearing a mask in indoor public settings, washing hands, covering cough and sneezes, and ventilating indoor spaces.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.