As flu season nears, some health experts brace for a ‘twindemic’

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Winter is ending in the Southern Hemisphere and country after country — South Africa, Australia, Argentina — had a surprise: Their steps against COVID-19 also apparently blocked the flu.

But there’s no guarantee the Northern Hemisphere will avoid twin epidemics as its own flu season looms while the coronavirus still rages.

“This could be one of the worst seasons we’ve had from a public health perspective, with COVID and flu coming together. But it also could be one of the best flu seasons we’ve had,” said Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

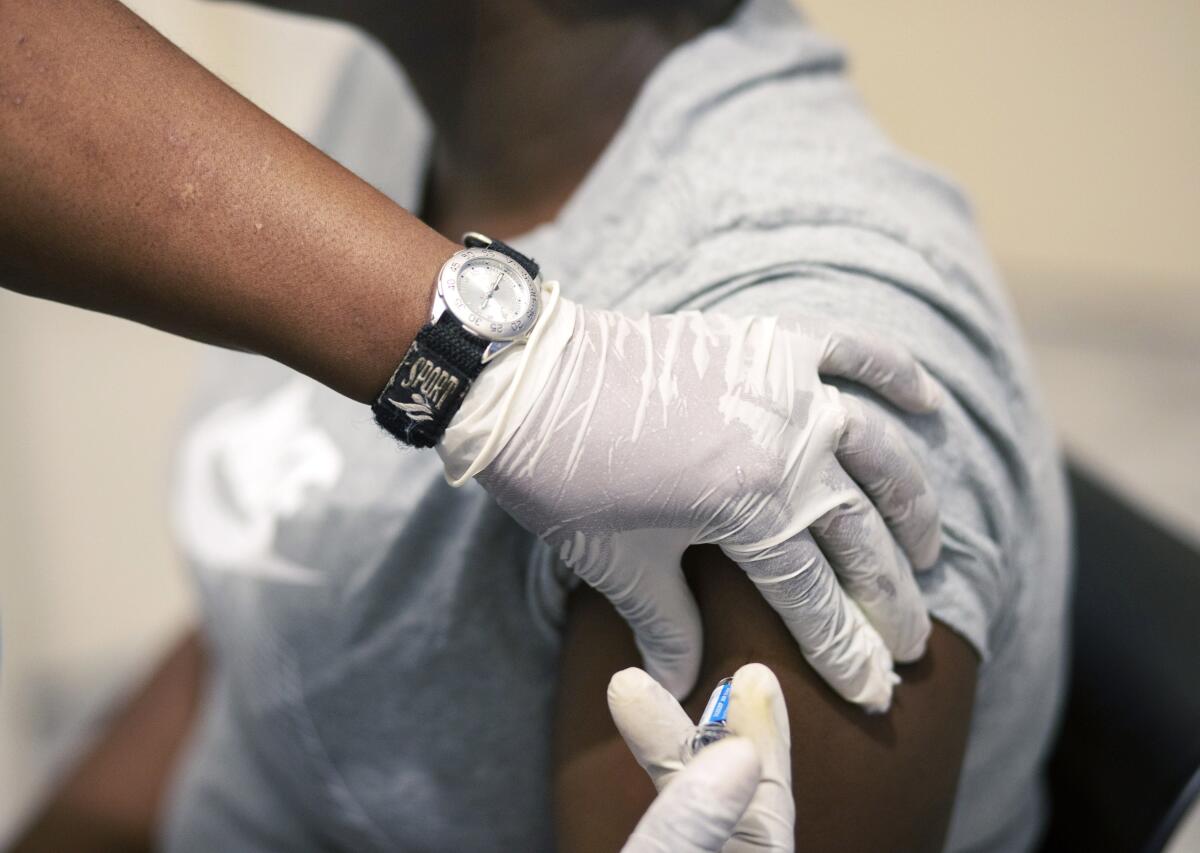

U.S. health officials are pushing Americans to get vaccinated against the flu in record numbers this fall, so hospitals aren’t overwhelmed with a dueling “twindemic.”

It’s also becoming clear that wearing masks, avoiding crowds and keeping your distance are protections that are “not specific for COVID. They’re going to work for any respiratory virus,” Redfield said.

The evidence: Ordinarily, South Africa sees widespread influenza during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter months of May through August. This year, testing tracked by the country’s National Institute of Communicable Diseases is finding almost none. That’s unprecedented.

School closures, limited public gatherings and calls to wear masks and wash hands have “knocked down the flu,” said Dr. Cheryl Cohen, head of the institute’s respiratory program.

That not only meant lives saved from flu’s annual toll, but it “freed up our hospitals’ capacity to treat COVID-19 patients,” Cohen added.

In Australia, the national health department reported just 36 laboratory-confirmed flu-associated deaths from January to mid-August. During the same period last year, there were more than 480.

“The most likely and the biggest contributor is social distancing,” said Dr. Robert Booy, an infectious diseases expert at the University of Sydney.

The coronavirus is blamed for about 24 million infections and more than 810,000 deaths globally in just the first eight months of this year. A normal flu year could have the world’s hospitals dealing with several million more severe illnesses on top of the COVID-19 crush.

Back in February and March, as the worldwide spread of the new virus was just being recognized, many countries throughout the Southern Hemisphere girded for a double whammy. Even as they locked down to fight the coronavirus, they made a huge push for more last-minute flu vaccinations.

“We gave many more flu vaccinations, like four times more,” said Jaco Havenga, a pharmacist who works at Mays Chemist, a pharmacy in a Johannesburg suburb.

Some countries’ lockdowns were more effective than others at stemming spread of the coronavirus. So why would flu have dropped even if COVID-19 still was on the rise?

“Clearly the vigilance required to be successful against COVID is really high,” Redfield said. “This virus is one of the most infectious viruses that we’ve seen.”

That’s in part because 40% of people with COVID-19 show no symptoms yet can spread infection, he said.

In a report released this month, the World Health Organization cautioned that the flu hasn’t disappeared. While “globally, influenza activity was reported at lower levels than expected for this time of year,” it found sporadic cases are being reported.

Plus, some people who had the flu in Southern countries might just have hunkered down at home and not seen a doctor as the coronavirus was widespread, WHO added.

The more people see wearing face masks and practicing social distancing as ways to protect the health of others, the more likely they are to comply, research shows.

But international influenza experts say keeping schools closed — children typically drive flu’s spread — and strict mask and distancing rules clearly helped.

“We don’t have definitive proof, but the logical explanation is what they’re doing to try to control the spread of [the coronavirus] is actually doing a really, really good job against the flu as well,” said Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, who is part of a WHO committee that tracks flu evolution.

In contrast, the U.S. and Europe didn’t impose coronavirus rules nearly as restrictive as some of their Southern neighbors. Even now, many of them are reopening schools and relaxing distancing rules even as COVID-19 still is spreading and the cooler months that favor influenza’s spread are fast approaching.

So the U.S. CDC is urging record flu vaccinations, preferably by October. Redfield’s goal is for at least 65% of adults to be vaccinated; usually only about half are.

The U.S. expects more than 190 million doses of flu vaccine to be available this year, about 20 million more than last year. States are being encouraged to try drive-thru flu shots and other creative ideas to get people vaccinated while avoiding crowds.

In an unusual move, Massachusetts has mandated flu vaccination for all students — from elementary to college — this year. Typically only some healthcare workers face employment mandates for flu vaccine.

In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson likewise is urging widespread flu vaccination.

To be clear, the flu vaccine only protects against influenza — it won’t lessen the chances of getting the coronavirus. Vaccines against COVID-19 still are experimental, and several candidates are entering final testing to see if they really work.

Doctors at Harbor-UCLA are participating in a COVID-19 vaccine trial, and they’re aiming to recruit people of color and members of other high-risk groups.

But for coronavirus protection, Redfield continues to stress vigilance about wearing masks, keeping your distance, avoiding crowds and washing your hands.

“Once one stops those mitigation steps, it only takes a couple weeks for these viral pathogens to get back on the path that they were on,” he said.

While the U.S. has been mask-resistant, most states now have some type of mask requirement, either through statewide orders issued by governors or from city and county rules.

Meanwhile, countries where flu season is ending are watching to see if the Northern Hemisphere heeds their lessons learned.

“It could be very scary — we honestly don’t know,” said Booy, the Sydney infectious diseases expert. “But if you’re going to get the two infections at the same time, you could be in big trouble.”