The battle for the Capitol ended. The war for democracy continues

- Share via

WASHINGTON — There are few clues left at the U.S. Capitol that American democracy hung in the balance a year ago.

Shattered windows have been replaced, blood wiped off the marble floors, tear gas residue cleaned from historic art.

As far as anyone walking around the building can see, the country has swiftly recovered from the Jan. 6, 2021, attack by thousands of Donald Trump supporters who unsuccessfully sought to block the certification of Joe Biden’s electoral victory.

But the lies that fueled the riot remain deeply embedded in American politics.

Instead of providing a foundation for national unity, Jan. 6 became a launchpad for disinformation and new state laws to restrict access to the ballot box.

Today, most Republican voters believe the last election was stolen, and many of the party’s politicians either believe the same falsehoods or are afraid to contradict them.

Visual coverage from anniversary events throughout the day marking the Jan. 6, 2021, attack.

A reminder came in Minnesota last month, when five Republican candidates for governor were asked during a debate whether President Biden had won the last election. None of them would say yes.

::

The violence last Jan. 6 might have appeared spontaneous, but then-President Trump had spent months feeding his supporters lies about the election. He warned during the campaign that there would be massive voter fraud, and he prematurely claimed victory on election night even as millions of votes had yet to be counted.

Days later, when Biden was declared the winner, Trump began filing lawsuits around the country. Although judges swiftly rejected Trump’s claims as meritless, his effort to overturn the election results didn’t end — it evolved.

The claims became more untethered from reality, and the methods became more aggressive.

Trump leaned on the Justice Department to intervene and prevent certification of the election.

His allies pushed for investigations into baseless conspiracy theories involving military satellites, voting machine tampering and foreign meddling by Venezuela and China.

Trump supporters gather in the U.S. capital to protest the ratification of President-elect Joe Biden’s electoral college victory over President Trump.

Trump called a Georgia election official and asked him to dig up enough ballots — “I just want to find 11,780 votes,” he said in their recorded conversation — enough to overturn Biden’s win in that state.

“There was a little cabal at work trying to turn this democracy into an autocracy,” Rep. James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.) told reporters last month.

By this point, Trump was already fixating on Jan. 6, the date when Congress would ceremoniously certify the results of the election. It was Vice President Mike Pence’s role to oversee the process, and Trump believed groundless theories that Pence could stop it.

Trump was furious when Pence refused. On Jan. 6, a cold and cloudy Wednesday in Washington, he spoke to supporters who gathered for a rally in sight of the White House and Washington Monument. He told them, “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” and then said, “We’re going to the Capitol.”

::

What happened next — the flood of rioters smashing into and through police lines, the bloody melee, five deaths — shocked even those who had spent the last four years closely scrutinizing Trump and trying to hold him to account.

“We anticipated just about everything that could go wrong,” said Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank), chair of the House Intelligence Committee and the lead House manager in Trump’s first impeachment trial, “except for what actually did.”

Little about what occurred at the Capitol is a mystery. The horror was broadcast live on national television, and many of the insurrectionists posted their exploits on social media.

Even some of Trump’s most ardent supporters were left aghast at the mayhem, according to text messages recently released by a special House committee investigating the assault.

“It has gone too far and gotten out of hand,” Donald Trump Jr., the president’s eldest son, said in a text to Mark Meadows, the White House chief of staff.

“The president needs to tell people in the Capitol to go home,” Laura Ingraham, a Fox News host and one of Trump’s staunchest allies in the media, texted Meadows. “This is hurting all of us. He is destroying his legacy.”

Once the building was cleared, Ingraham condemned “today’s antics at the Capitol” in her prime-time show, but insisted that “more than 99%” of the Trump supporters were peaceful. She also suggested that “antifa sympathizers may have been sprinkled throughout the crowd,” an allegation for which no evidence has emerged.

The shift from outrage to equivocation or denial has characterized the Republican Party’s response to Jan. 6. Party lawmakers who voted for Trump’s subsequent impeachment now face primary challenges, and one of the former president’s most outspoken GOP critics, Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, was forced out of her position in caucus leadership.

“The Republican Party has to make a choice,” Cheney tweeted on Sunday. “We can either be loyal to our Constitution or loyal to Donald Trump, but we cannot be both.”

Even Trump’s vice president — whose name had echoed through the Capitol as rioters chanted, “Hang Mike Pence!” — has found ways to brush off the day’s events.

“I know the media wants to distract from the Biden administration’s failed agenda by focusing on one day in January,” he told Fox News in October. “They want to use that one day to try and demean the character and intentions of 74 million Americans” — referring to Trump’s vote total, which was 7 million less than Biden’s — “who believed we could be strong again and prosperous again.”

Despite being barred from Twitter and Facebook, Trump remains influential among Republicans. Some politicians who once condemned the violence have refused to confront him or his efforts to undermine democracy. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) falsely claimed in May, “I don’t think anybody is questioning the legitimacy of the presidential election.”

Trump never stopped. He has described the election as the “real insurrection” and Jan. 6 as “a day of protesting the fake election results.” He talks about Ashli Babbitt, a rioter who was shot and killed by security as she tried to breach an area near lawmakers, as a martyr.

“Please know that her memory will live on in our hearts for all time,” he said in a video message recorded for an October event in Babbitt’s honor.

Trump originally planned to hold a news conference at Mar-a-Lago, his Florida resort, on Thursday to mark the attack’s anniversary. But on Tuesday he canceled the event, saying the media “will not report the facts.” He plans to continue holding rallies to repeat the same lies that led to the Jan. 6 assault, with the next scheduled for Jan. 15 in Arizona.

The former president’s falsehoods remain a central part of his plan to dominate the Republican Party. It’s a campaign of disinformation that experts said could fuel future attacks, especially when mixed with potent fears about white people losing power in a diversifying country.

“I don’t think we are out of the woods at all,” said Javed Ali, a former senior director for counter-terrorism at the National Security Council. “And I think this threat is going to last for years, if not decades.”

::

Trump uses support for his lies as a litmus test for Republican candidates, dangling endorsements in front of those who cast doubt on the 2020 election’s validity.

In Arizona, he endorsed Kari Lake, a former television broadcaster running for governor who falsely claims Trump won the state. In Georgia, he pushed David Perdue, a former U.S. senator, to run in the GOP primary against Gov. Brian Kemp, who refused to block the certification of Biden’s victory there.

Polls show that most Republican voters believe Biden’s victory was fraudulent. Those beliefs have spurred state lawmakers to accelerate long-standing campaigns to restrict voting options and change how elections are managed.

For example, Georgia made it harder to request mail ballots and barred election officials from sending voters unsolicited applications for those ballots. No one is allowed to offer food or water to people waiting in line to vote.

In addition, the Republican-controlled Legislature appointed a new chair of Georgia’s election board, which has been empowered to suspend county election officials for alleged malfeasance or mismanagement.

Similar efforts to change voting rules have stalled in other battleground states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, where Democratic governors have vetoed legislation passed by Republican lawmakers. But these governorships are up for election this year, opening a potential pathway for the proposals to advance.

“This is a five-alarm fire,” said Richard L. Hasen, an election expert at UC Irvine School of Law. “People are exhausted between Trump and COVID, and I think people have tuned out. And I think this is very dangerous.”

::

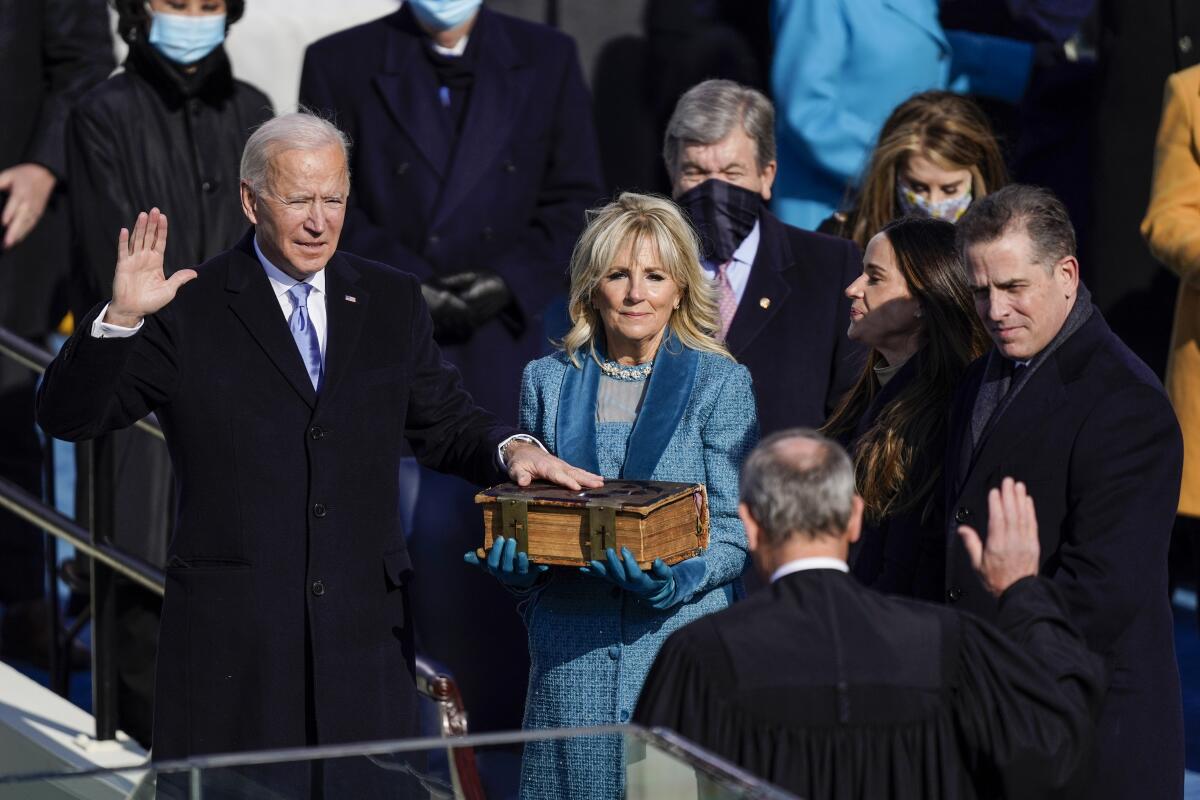

When Biden was inaugurated outside the Capitol two weeks after the riot, he walked through a door with cracks in its glass panel. It was a sign that the transfer of power, unlike every previous one since the Civil War, had not been peaceful.

But the window was soon fixed, much like everything else in the building.

Damaged materials have been boxed up and handed off to the Justice Department for use as evidence in ongoing federal prosecutions of rioters. (More than 700 people have been arrested on federal charges tied to the insurrection.)

The Architect of the Capitol, the agency responsible for maintaining the building, plans to reclaim the wreckage as artifacts later. Eventually they could serve as a public testament to the resilience of American democracy — or how it crumbled.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.