In the post-pandemic world, the U.S. economy could be totally different

- Share via

WASHINGTON — When the U.S. economy reopens, whether sooner or later, chances are it won’t look the same as it did only a few months ago before the coronavirus outbreak.

And the wider and deeper the pandemic runs, the more profound the future changes in American life are almost certain to be. Already the climb out of the deep economic hole looks to be long and slow.

“The world that we are going to live in for at least the next two to three years will be totally different than what we are used to,” said Sung Won Sohn, president of SS Economics and professor at Loyola Marymount University.

“Because of the psychological shock that we have experienced, we are going to be more cautious, and we will probably spend less and save more, and we will have fewer contacts with other individuals,” he said. “We are going to be suspicious about things, [such as] whether people we are meeting have the virus and will the economy fall back down again.”

More stimulus from Washington, especially large-scale spending to upgrade infrastructure, could help offset some of the negative long-term effects of the pandemic, though it will mean huge additions to the national debt.

Even so, millions of Americans will struggle with lost income, heavier debt, and reluctance to spend whatever cash they may still have because they are apprehensive about the future.

California’s jobless rate shot up in March as coronavirus shutdowns took effect and 2.7 million filed unemployment claims in just a month

Businesses, especially smaller ones, will also face new debts and expenses. To reopen, they’ll need to spend money upfront for staff and supplies, without knowing when or whether customers will return.

“Every restaurant that reopens is going to be basically a start-up, an interesting concept with no money and desperate for cash,” said Sean Kennedy, executive vice president at the National Restaurant Assn.

For large corporations, business leaders and strategists say that the pandemic will accelerate the trend away from dependence on global supply chains. That may make the U.S. economy more self-reliant and bring home some jobs, but it will also impose new costs on businesses and higher prices on consumers.

For decades, shifting production to lower-paid workers overseas kept American consumer prices lower and helped offset the small-to-nonexistent growth in real wages and salaries for all but the most affluent.

More domestic production means higher costs and higher prices. Those in turn will lead to demands for higher wages, even for the least skilled workers, along with more labor and political strife.

Many of Mexico’s border factories are flouting orders to suspend operations, worsening the spread of the coronavirus.

Inflation, negligible for decades, could return, adding to the problems of individuals and the country as a whole.

In the near future, adapting to new considerations and guidelines on health and safety, particularly social distancing, may be the most disruptive and urgent task for many businesses.

Restaurants, bars, hotels and entertainment venues like theaters and sporting arenas were among the earliest to close, accounting for many of the 22 million workers laid off or furloughed in the last month.

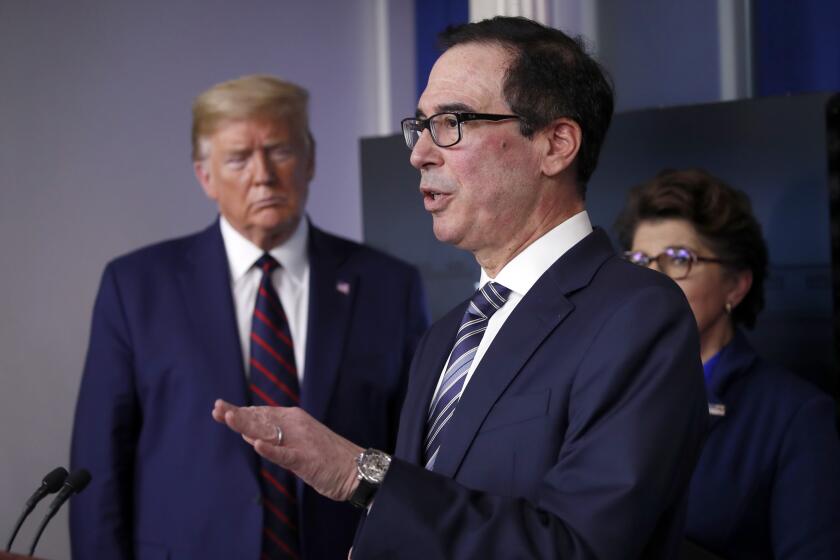

President Trump’s guidelines Thursday for reopening the economy left to state governors to determine just when and under what terms businesses can resume operations. So it’ll be up to them and local health officials to spell out what constitutes a safe distance for customers and workers alike.

If experience in the earlier stages of the pandemic is any guide, that will mean wide variations in what the new policies will be.

In Beijing and much of China, restaurants have been told to maintain a little more than three feet of separation between tables. Some are limiting diners to three to a table.

Small businesses may have gotten coronavirus relief from the Paycheck Protection Program based on which bank they picked, not how early they applied.

Such strategies may reduce infection, but they also mean less income for the restaurant.

Paul Herber, whose Bellevue, Wash., company Ascend Hospitality Group operates 13 restaurants in the West, sees no easy answers.

He is looking at possibly yanking some tables to open up space between diners, putting up see-through barriers between booths, and imposing far more rigorous cleaning procedures.

Even then, Herber worries about how to control waiting-list crowds during busy weekend nights and what he will do if he can no longer have corporate groups that typically number six to 10 in a table.

“How do we make money with those peak periods being handicapped?” he asked.

Robert Cole, a senior analyst at Phocuswright, a major hospitality market research firm, said, “I think this is going to be a sea change for the industry.”

“For some, it’ll be an existential battle,” he said. “Group meetings and conventions are going to be changed forever. Corporations are going to take a scalpel to their travel budgets.

“The number of salespeople on the road,” he added, “I think that’s going to be reduced. Even if there’s a cool medical breakthrough, even if that happens, I think people are going to say, ‘Wait, do we really need to send all those people?’”

Less travel may appeal to workers, especially those who have adjusted to child care and other aspects of their lives as a result of working from home for several months. But it’s lost business for airlines, hotels, car rental companies and related industries.

Here as most everywhere else, there are ripple effects of changes that are hard to foresee and likely to be painful for some.

On leisure travel, Cole said: “The optimists in the industry are saying, ‘Hey, there’s all this pent-up travel demand. People are just hating being at home and they want to get out and hit the road. Well, they aren’t going to do that until it’s safe. That’s one issue: the fear and trepidation. Another one, though, is the longer this goes on, do they have the disposable income to travel?”

It’ll be even more tricky to manage large public events in sports stadiums and music halls, although those too will be based on size and the ability to control crowds.

John Fithian is president of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners, a trade group that represents 33,000 movie screens across America, all of which have been dark since mid-March.

Fithian says his members have the advantage of spacing out reserved seating and reducing clustering by staggering movie start and end times. By June he expects all the movie houses to reopen, and a month later, Hollywood studios hope their delayed new releases will turn into late summer blockbusters.

“People will be so cooped up in another month or two — in fact, they’re cooped up right now — that when the coast is clear, so to speak, people are going to pour out of their houses to go and watch a movie,” Fithian said.

That may be, but moviegoing was trending downward before the pandemic. Now many people have become more accustomed to entertaining themselves at home via cable, streaming and even books and games.

It may be instructive to remember that after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, it took three years for airline traffic to return to earlier levels.

And it’s not just that companies and people will be watching their expenses — or that globalization is in retreat — that could cause a long-term reduction in international travel. Over the past two months of widespread telecommuting, companies and individuals have learned that a lot can be done effectively over the internet.

Amy Myers Jaffe, an energy security expert who teaches at Columbia University, remembers flying to Asia for a short meeting and coming back the next day.

“Now that you realize that Zoom and Skype and all these things work, would you ever fly to Singapore for a one-hour meeting again?” she wondered.

Jaffe speculated about permanently reduced demand for oil if many workers continue to work from home after the pandemic passes.

“Maybe your boss is going to let you work remotely on Friday. Multiply that by everyone in the country, that’s a lot of people not driving to work,” she said.

Advances in information technology revolutionized where and how products are made, as well as how they’re transported and distributed — and they are almost certain to undergo a major transformation in the aftermath of the pandemic.

That will help accelerate corporations’ new emphasis on resiliency instead of cost efficiency.

For decades, multinational firms relentlessly sought to raise profits by scouring the world for cheap materials and producing goods in the cheapest, most efficient manner.

That commonly meant sourcing goods from far-flung suppliers and producing on a just-in-time basis to keep just enough inventory on hand and squeeze as much efficiency and profit out of the system.

Now the buzzword is going to be resiliency — that is, “the ability to absorb a shock, and to come out of it better than the competition,” said Kevin Sneader and Shubham Singhal of the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. That, they said, “will be the key to survival and long-term prosperity.”

Supply chains already were coming under pressure as tariffs, trade wars and more restrictive borders and immigration drove many companies to rethink their production schemes. COVID-19 clearly has accelerated that trend.

More than a quarter of American companies operating in China said they planned to shift sourcing of materials or supplies because of the pandemic, in some cases moving them outside China, according to a March survey released Friday by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai.

China has long been the dominant and low-cost link in global manufacturing and trade, and any major shift away from there will cut into the profits and raise prices for both retailers and consumers.

Large retail chains in the U.S. already were diversifying their supply sourcing. And now they have even more work cut out for them in the wake of the pandemic.

They face increasing pressure to raise wages and provide better benefits such as sick leave, and many are looking at how they can reconfigure their physical stores — such as widening aisles and making them one-way — and doing away with cash and credit card hand exchanges, even as they feel even more heat from internet rivals such as Amazon.

“We have a lot of issues to work through,” said Jonathan Gold, vice president at the National Retail Federation. “How do you reimagine the store in this environment?”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.