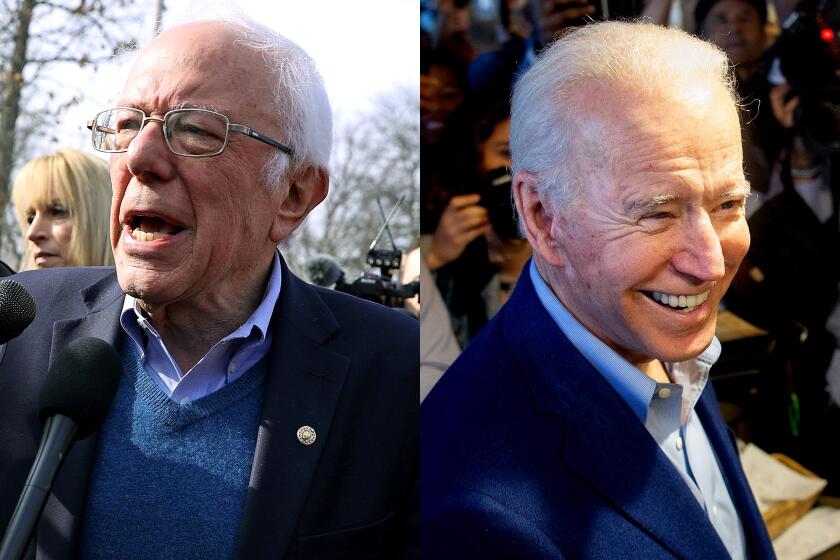

Democratic debate shows the new shape of the 2020 presidential race

- Share via

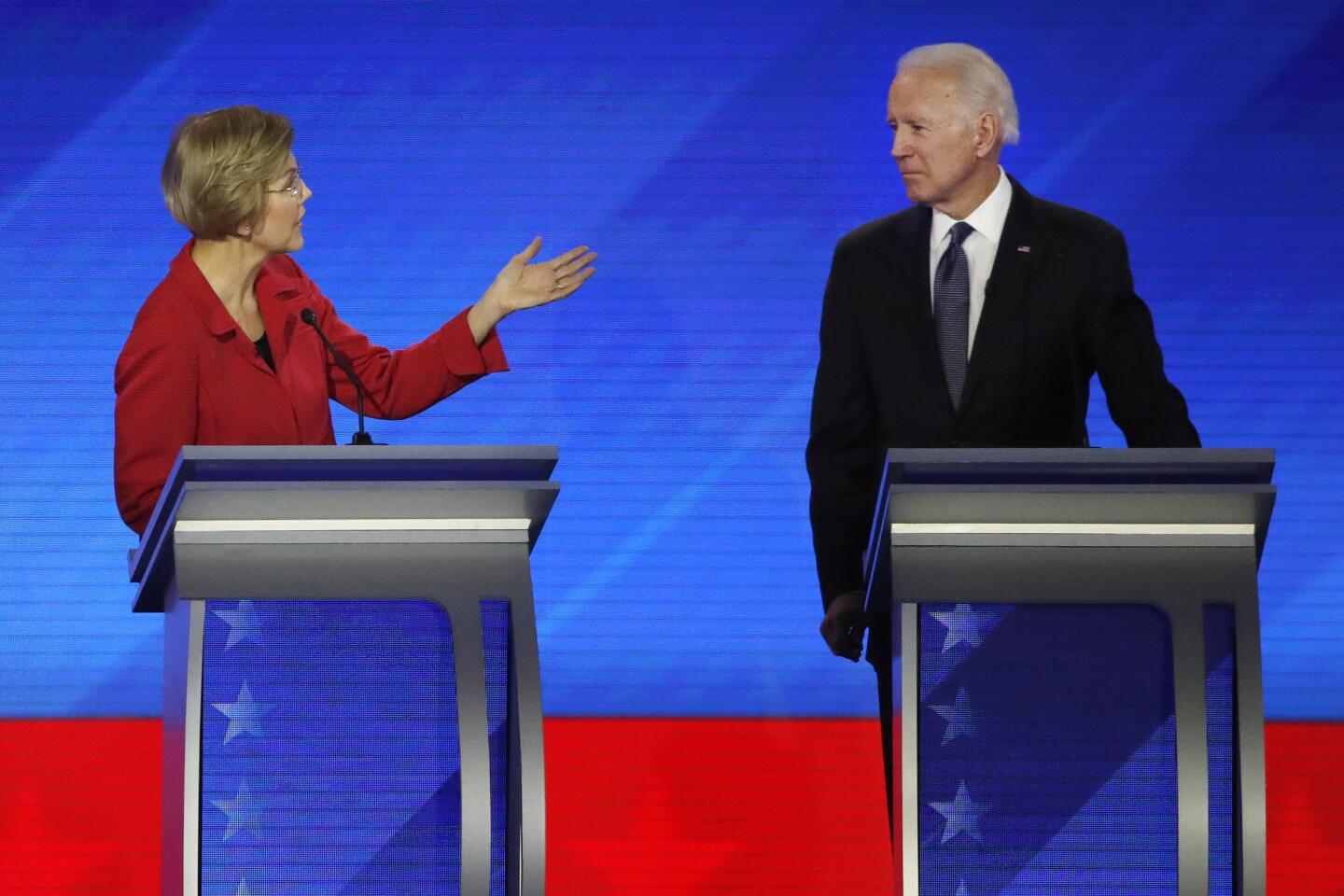

MANCHESTER, N.H. — The new shape of the Democratic presidential race became apparent within minutes after Friday night’s debate began: Former Vice President Joe Biden stood at the middle podium, but no longer at the center of attention.

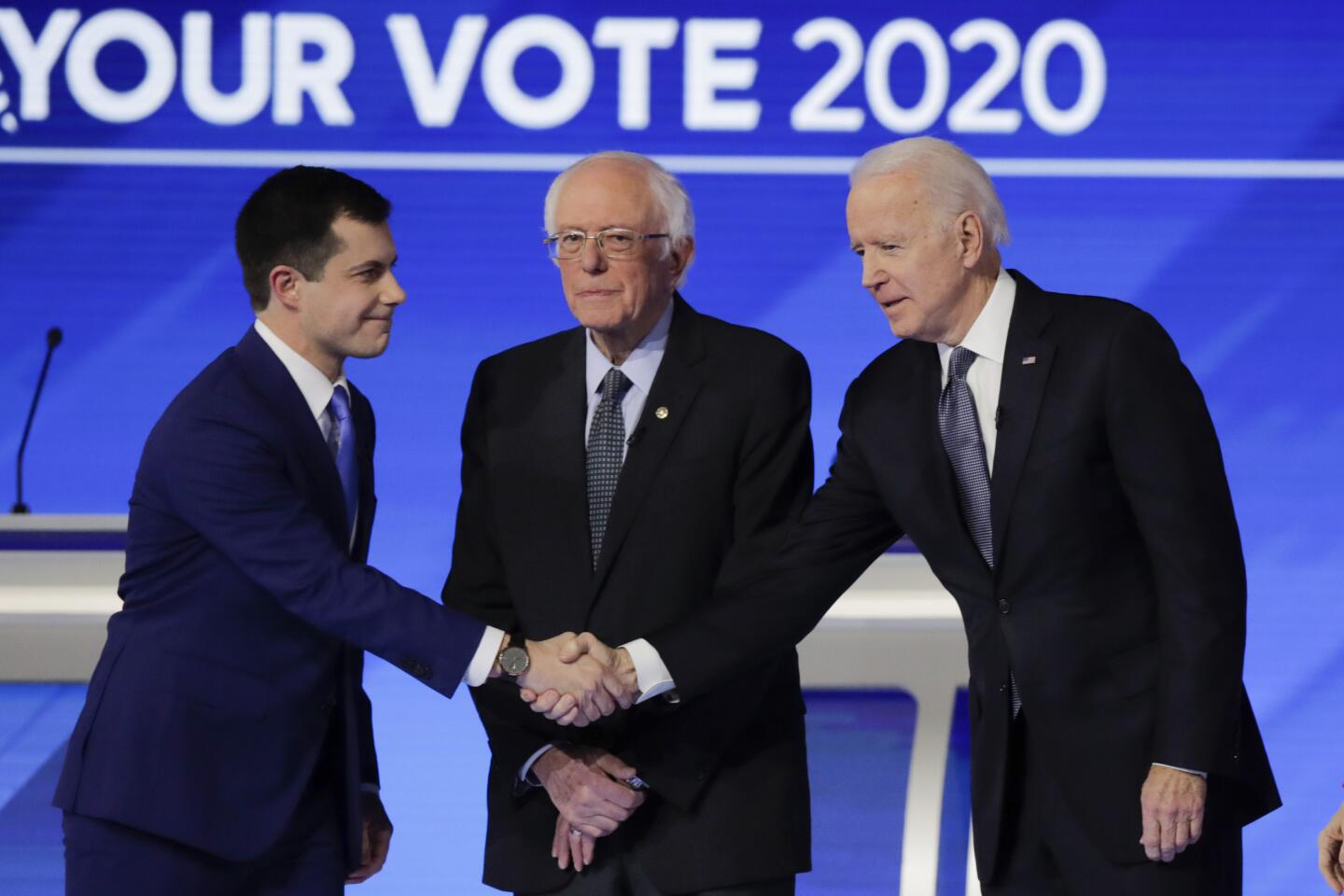

The night’s most energetic exchanges involved Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders — the two winners coming out of Iowa’s caucuses this week who consistently lead polls of this state, as well.

Hours before the debate, Biden’s aides said he would take a more aggressive tack in drawing contrasts with his rivals. On the stage, however, the new Biden seemed much like the old one, except slightly louder.

Early on, Biden did criticize the two leaders — using lines he had tested on the stump Wednesday. Later in the debate, he rebuked Sanders for his opposition to gun control measures in the 1990s. But for a candidate badly in need of a change in direction, he had relatively little new to say.

Perhaps more tellingly, both Sanders and Buttigieg passed up chances to criticize the former vice president, husbanding their time to go after each other. Going further, Buttigieg at one point defended Biden against attacks from President Trump on his son Hunter.

“The vice president and I and all of us are competing, but we’ve got to draw a line here,” Buttigieg said. “We as a party have to be completely united.”

The debate came as the Democratic contest increasingly has taken on the shape of not a two-person race, but a two-lane one.

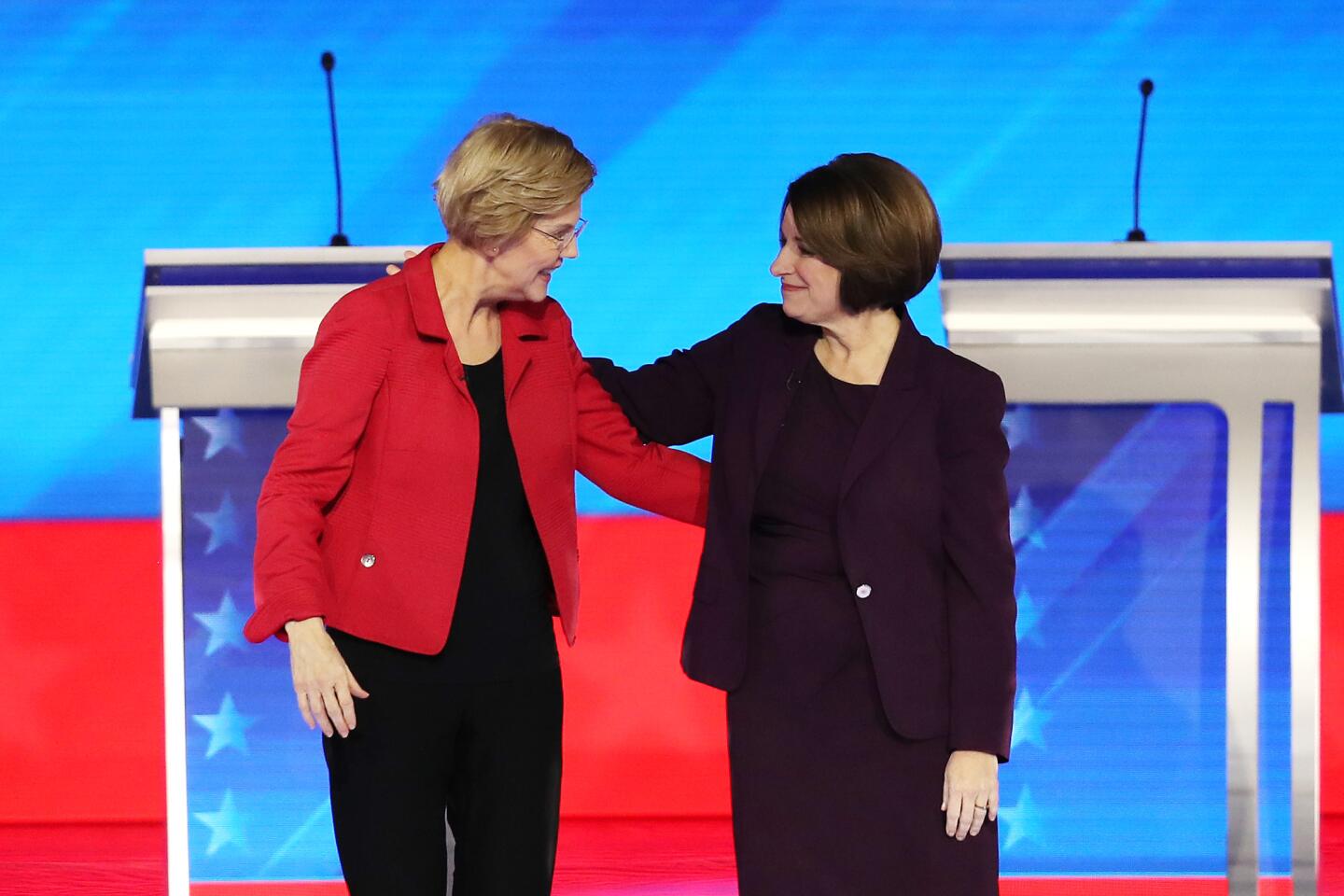

In one lane, Sanders dominates, having taken a clear edge with progressive voters over Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

The other lane is for voters who think Sanders stands too far to the left. That “not Bernie” lane includes Biden, Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg. The billionaire skipped New Hampshire and the other three states that hold February contests, but looms as an increasingly large presence in the 13 states, including California, that vote March 3.

Here are key dates and events on the the 2020 presidential election calendar, including dates of debates, caucuses, primaries and conventions.

Biden has been slipping behind Buttigieg in that moderate lane, and his slide accelerated after the fourth-place finish in Iowa that he admitted Wednesday came as a “gut punch.”

Buttigieg, by contrast, got a boost by sharing the Iowa lead with Sanders.

His effective tie with Sanders there has galvanized the attention of voters here. It has also energized Buttigieg’s donors, giving him and an allied super PAC the resources to run far more advertising in the state than Biden and his allied super PAC have been able to muster.

Multiple polls of New Hampshire voters in the last week have shown Buttigieg on the rise, moving into a near tie with Sanders — and even edging in front in one tracking poll released shortly after the debate ended. Biden has slipped behind into third or fourth, depending on the survey.

The forecast of a more aggressive approach for Biden reflected the gravity of that position.

His aides say he will do better once the action moves to states whose electorates are less white than those in Iowa and New Hampshire. That may well be true, and Buttigieg continued to show that he has no effective answers to questions about how as mayor he dealt with racial bias in his city’s Police Department.

But Biden’s problem is that a candidate who bases much of his appeal on the promise of electability has a unique vulnerability to the stigma of losing.

Presidential politics has several examples of front-running candidates who stumbled into New Hampshire, righted their campaigns and went on to win their party’s nominations. Walter Mondale did so in 1984; George H.W. Bush did in 1988. Bill Clinton parlayed a second-place finish here in 1992 into a successful “Comeback Kid” narrative that carried him on to victory.

Those examples may no longer provide much help to Biden, though. To start, New Hampshire is a bad state for him, even more so than Iowa. It’s not only nearly all white, but its Democratic electorate tends to be white-collar. The voters who back Biden — older, blue-collar Democrats and African Americans — are scarcer here than in almost any other state on the primary calendar.

The danger for Biden is that voters may simply begin to discount him as a factor in the race and move on to others, either those who shared the stage with him, or Bloomberg.

The potential for that sort of discounting could be seen early on when debate moderator George Stephanopoulos gave Buttigieg an opening to criticize his rivals. The former mayor focused explicitly not on Biden, but on Sanders.

“The next president is going to face challenges the likes of which we hadn’t even thought of a few years or decades ago,” Buttigieg said. Democrats, he went on, “need to unite this country” and can’t do so “when our nominee is dividing people with the politics that says, ‘if you don’t go all the way to the edge, it doesn’t count,’ a politics that says ‘it’s my way or the highway.’”

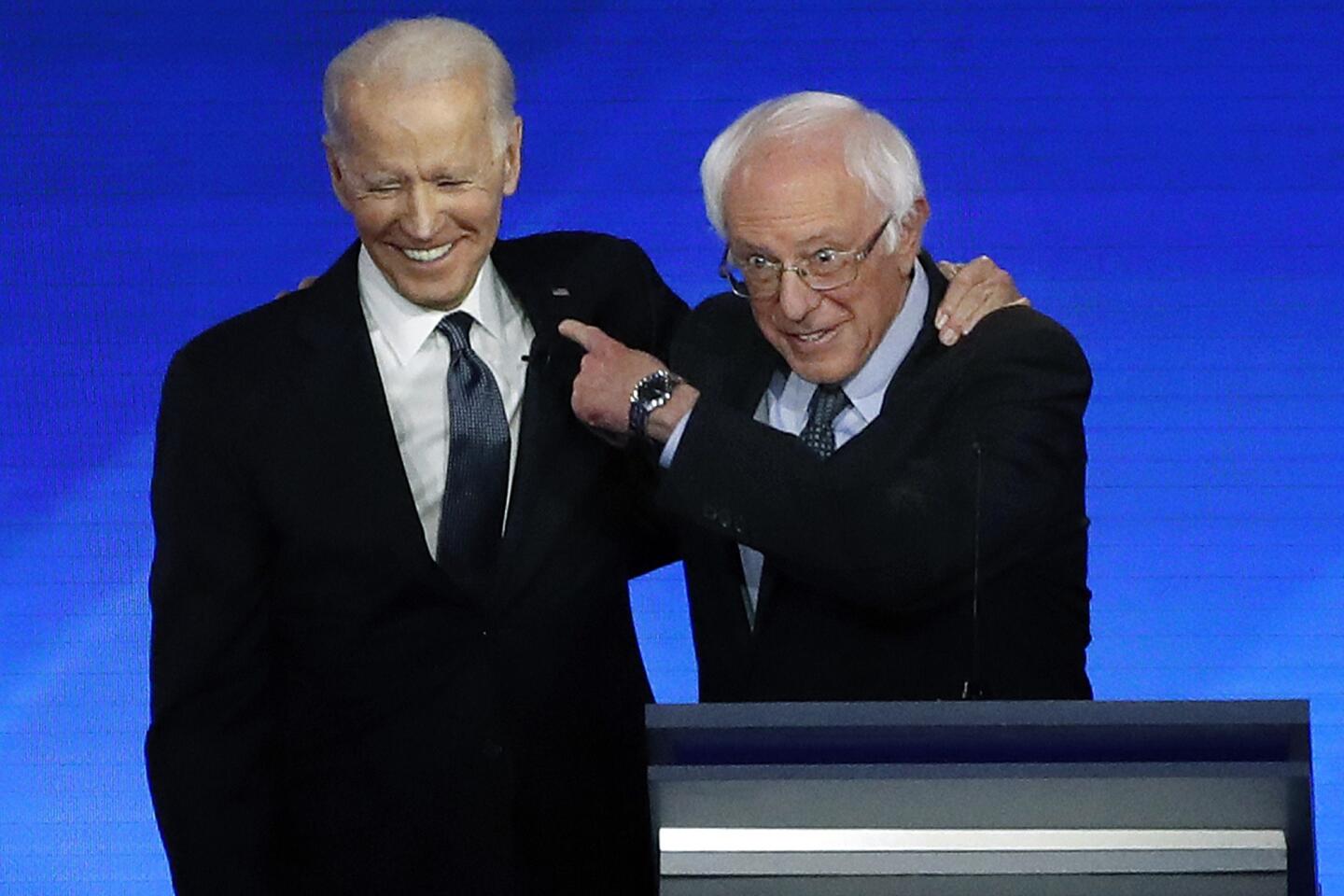

Sanders denied that was his approach, and later returned fire with a sharp attack on Buttigieg’s fundraising.

“I don’t have 40 billionaires, Pete, contributing to my campaign,” he said, touting the more than 6 million individual, small-dollar contributions he has received.

“If we want to change America, you’re not going to do it by electing candidates who are going out to rich people’s homes begging for money,” he said.

Sanders is well known to the voters here, having won more than 60% in the primary four years ago against Hillary Clinton. In New Hampshire, however, he now faces a problem of expectations: He clearly won’t replicate his 2016 majority in a much larger field, but anything less than a significant victory here would appear as a setback.

In contrast to Sanders, Buttigieg shows all the classic signs of a candidate riding a wave. Voters who had vacillated about supporting him have started to come over to his side; others who hadn’t considered him are giving him a second look.

Buttigieg remains significantly less known than Sanders, and he used the debate to repeatedly stress one of his key themes — that the country needs to “leave the politics of the past in the past, turn the page, and bring change to Washington before it’s too late.”

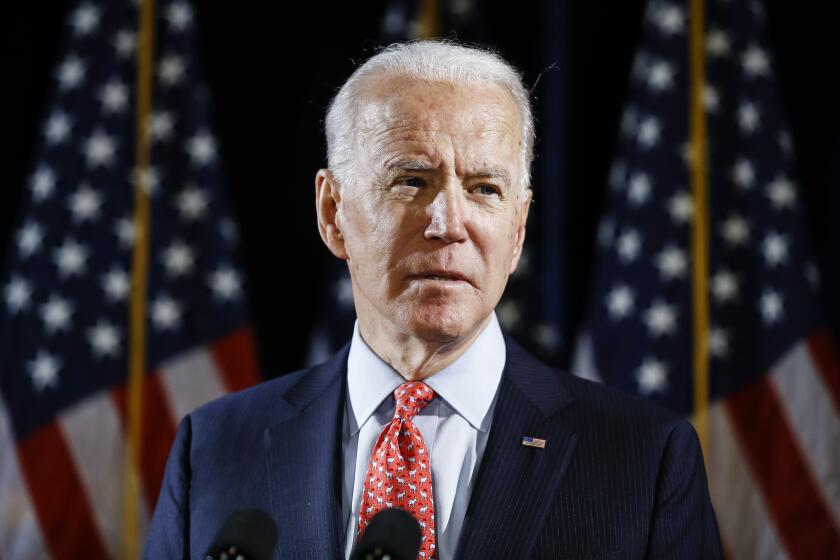

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

That call for a generational transition is one that has often appealed to Democrats and which works equally well against both of the septuagenarian men standing on the stage with him.

It’s a contrast that Biden may have inadvertently played into when, at one point, he defended “the politics of the past” saying they “were not all that bad.”

“I don’t know what about the past of Barack Obama and Joe Biden was so bad. What happened? What is it that he wants to do away with? We were just beginning,” Biden said.

The 38-year-old former mayor responded by complimenting President Obama’s record.

“Those achievements were phenomenally important, because they met the moment,” he said. “But now we have to meet this moment, and this moment is different.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.